A descendant of the Amazigh people reflects on the liminal spaces of the famed O‘ahu museum and the vast Moroccan terrain.

Ghosts live in forgotten places. They’re in dusty basements and abandoned structures, in memories we’d rather not have, and in the forsaken ancestry of our blood. I imagine that these ghosts feel similarly, existing in a perpetual state of absentminded frustration, like the feeling of walking into a room for a reason you can’t remember. They wail, knock things off walls, and bang on the floor, asking for attention but without objective. They forget they’ve been forgotten.

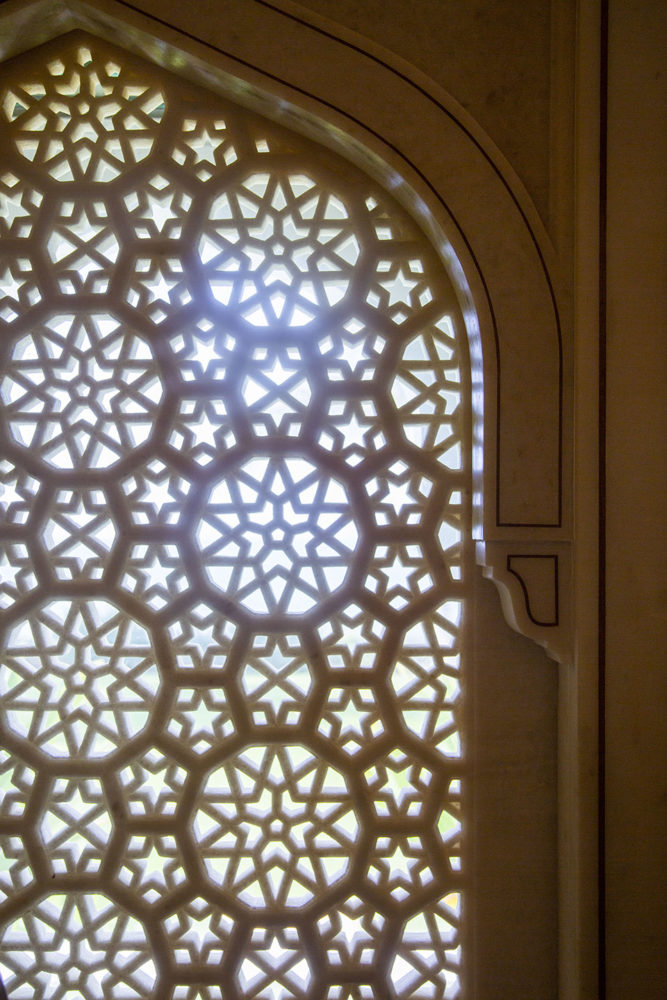

A sudden global pandemic suspended visits to Shangri La, now sitting in silence. I can’t help but wonder what this space—the former Honolulu estate of Doris Duke, now a museum for Islamic art, culture, and design—must feel after so many years of wild parties, gatherings, and visitations from people near and far. It’s safe living at the edge of an island, like the tobacco heiress who once called it home. Shangri La’s vast collection of art, textiles, ceramics, and all forms of rarities removed from their original homes now exist only for themselves.

Image by Sera Lindsey

Image by Sera Lindsey

And what of the mosques and storefronts in Morocco? Many bear the same scars as those relics now in Hawai‘i. Both are haunted by the sudden stillness of quarantine. Maybe, in the quietude, they can hear each other.

Some of the same items found in Shangri La, like the 17th-century decorative tiles that line the walls and floor, painted bowls and hand-carved tables, and a small Quran encased in glass, are kept in better shape in their homeland because they are used. Others fall apart for the same reason.

I feel hot and cold waves of discomfort when I see spaces shamelessly dripping in the traditional decor and handmade crafts of my ancestors. The Amazigh people, recognized domestically as “Berber,” are a vulnerable culture thanks to the fame of their rugs and other marketable goods.

It’s a sad awareness to find that bookstores are a desert when seeking information about these indigenous North African tribes, but when searching for Moroccan interior and “style inspo” books, you’re spoiled for choice. The sensitivity I carry offers me an extended awareness of the susceptible nature of many other cultures teetering on the sharp edge of self-sufficiency and exploitation.

I’ve lost count of the brand names reflecting an out-of-touch notion of the exotic Indian brave. Native Hawaiians suffer the same ignorant corporate treatment. Clothes and home goods emulating styles and designs of indigenous peoples from around the world are so common we’re often blind to it. “Internationally inspired,” they say.

Doris Duke possessed a certain passion for beauty. The collection that she amassed within a 60-year period contains centuries of life. I felt that same life when I visited Morocco. It pulsed through the space between walls, all the items and people that filled them, and the very earth itself.

The relationship between what is preserved behind glass and what is passed down through family looks very similar, but with incomparable outcomes. There are no answers at Shangri La, only feelings and nonlinear lessons.

Image by Sera Lindsey

Image by Sera Lindsey

The museum’s collections contain authentic goods bought, commissioned, or acquired by sometimes unknown means. They are expressions of a kind of endangered magic, either kept in quiet seclusion or made public with access protocol. Something as mundane as a weaving comb becomes a treasure among an affluent audience. Sometimes the application of delicacy or preciousness to age-old customs and foreign objects can suddenly make them very fragile or, worse, devoid of meaning.

While these aspects of culture can inspire creativity, they were not meant to exist behind glass. Yet here they are at Shangri La, just as I am.

Perhaps it’s important to remember that I too was adopted from my birth land. I didn’t have a choice in the matter, and I was brought to this country for the sake of goodwill, after all. Perhaps there is no ideal, just a series of decisions that might feel right at the time.

I wish peace upon these ghosts, haunting the forgotten and restricted alike. May a rebirthing of sorts be granted to the ones who flow in our veins. Morocco lives within me as I live now, and these ghosts of my ancestry persist. Perhaps a rebirthing of sorts is granted to the ones who flow in my veins.

When considering the simultaneous existence of myself and the objects of my heritage, I’m encouraged to think of my own being. The questions pile and tip like dirty dishes. Answers sometimes come at an irregular pace.

I’ve learned that the purpose of these inquiries is not to find answers, but to give life to those who have been forgotten, and to myself in the process. I wish peace upon these ghosts, haunting the forgotten, restricted, and the soon-to-be rebirthed.