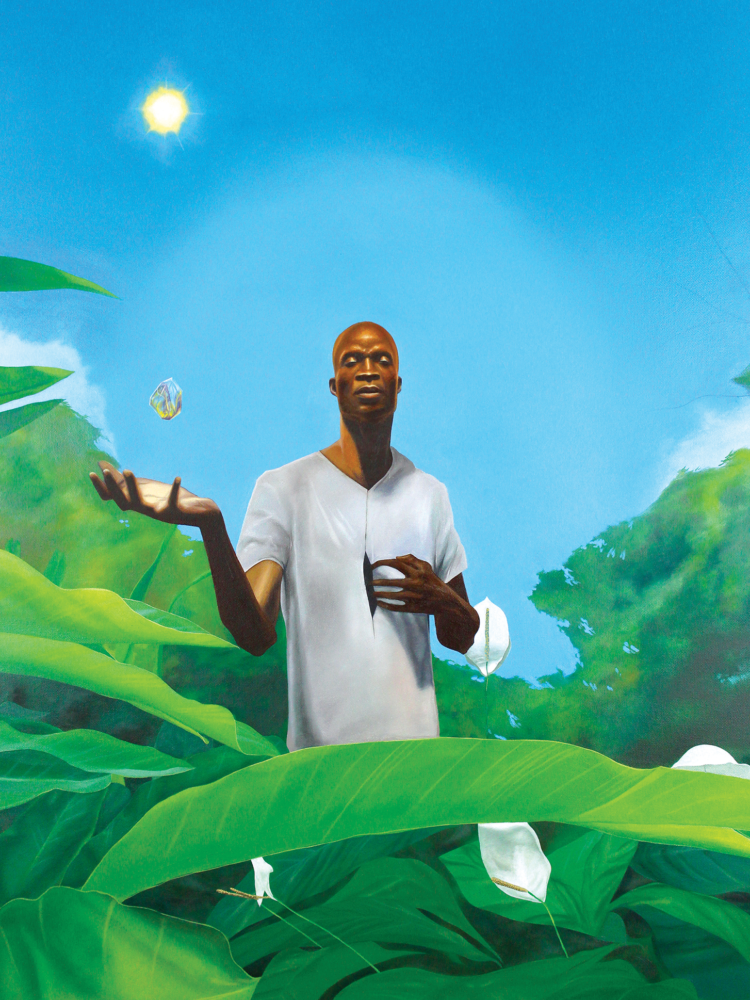

The Caribbean-born, Hawai‘i-based artist richly humanizes the African diaspora with abundant creations centering Black joy and love.

Mark “Feijão” Milligan II is a child of St. Croix, U.S. Virgin Islands, and is a contemporary Hawai‘i-based artist who is imagining and creating abundantly powerful representations of Blackness. He works in figurative painting and drawing to invite conversations that reveal the humanity of Black people across the diaspora. In dialogue with Krystal Hope, pay attention to the finest details in Milligan’s paintings and viewers will notice intentionally integrated influences of the Hawaiian Islands reflected in the stories he tells.

As a child of St. Croix, Virgin Islands, how does your identity play a role in how you express yourself through your art?

From an early age, I found identity to be very important. That was the catalyst for a lot of what I continued to do even today. When I was 11 or 12, I was leaving our house, walking up the street to catch a bus. I was passing by all our neighbors, and I remember how much of an impression it made on me, seeing all these beautiful households of people of African descent, people who are Afro Latino, and people from Puerto Rico. You also have different faiths too. I was very present in that moment, taking it in with a lot of pride. I remember feeling like, not necessarily making a comparison to anything else, but feeling very full. Like, “Wow, this is like such a beautiful community.” I’m leaving my house, but I’m still in a community that’s so strong. We pass by each other, hail each other up, greet each other — this was all just in a walk from my house. I remember at that moment also thinking about the portrayal of my community and this area that I lived in and all these neighbors in mainstream media, and seeing how different it was, how twisted and one-sided, and foreign their perspective of our community was. I knew at that point that I had art inside of me. I knew that even as one person, I’m going to do what I can to affect some kind of change. If I’m not seeing it outside of me and I’m feeling all of this within me, I’m going to be a creator. A part of it was for myself and for other people too.

What does your creative process look like?

Oftentimes my work tends to be a response either to something that I’m feeling internally or something that I’m seeing. Typically, I’m seeing portrayals that are very different from my experience. What I started to do in those moments is to tell the story myself. It becomes a situation where I just kind of sit and think of things that move me. I think in something of icons. For example, a couple of years ago, I was in church and I was sitting in the pews and I was seeing these images of Caucasians portrayed as Jesus Christ, as Mary, portrayed with reverence and respect. But then, we’re also going into the text and we’re talking about Egypt and the Middle East. Then when you see these places in National Geographic or other travel publications to reference the geography, the people that I’m seeing on the walls are not matching up. I really started to play with that. Fast forward a couple of years later, I actually got a little bit of trouble during my religious teachings because I would bring it up quite often. [Laughs] For my process, I see something that needs to be adjusted and I do a piece that kind of responds to it. It’s a conversation against untruths that need to be corrected. Then it just flows from there.

What dialogues are you hoping to inspire? Is there a certain conversation that you think folks should be having around your art?

The main thing I want the viewer to do is recognize the humanity of the African diaspora. Because I find that so often we are treated as something different. There is a lack of empathy by the mainstream media. It’s really important for there to be a humanization to realize that our stories are real, that our stories are not always this one-sided portrayal of pain, of a lack of history, of impoverishment, of sickness.

There’s so many things that are sometimes associated with the Black experience, but coming from my situation, there was abundance, there was a strong social structure. I had a strong family around me. I grew up very healthy. I grew up understanding my history and realizing that my history did not begin with enslavement, and realizing that my history is actually the history of everyone. Because if you really look at it, all people’s history connects to Africa, our history is long. We come from a culture that really needs to be celebrated in a certain way. So that’s what I try to capture within the pieces because I feel like oftentimes we only get little snippets in time. But if you look down the line, if you look over the years, you can see the continuity and these moments are forming a sentence, they’re forming a structure. The larger story is that there’s so much more to us than we are given credit for. So if the credit isn’t going to be given, I’m going to become a vehicle for telling this story. The question that I want people to have when they see it, if they’re not from the community, is to express a certain amount of curiosity without an immediate prejudice. I would like to inspire them to kind of realize that our story runs deep.

I love that. I do get that. I can see that you want us to see ourselves. That’s something I’ve been interested in and has inspired a lot of my research and work in communications because I don’t like the way I see myself portrayed. I often ask myself how I can influence that. You’re asking that as an artist. What do you think we lose or gain by seeing ourselves or not seeing ourselves?

By not seeing ourselves there’s a diminishing of a person. By not seeing ourselves, I think there’s a lot of questioning. By not seeing ourselves, we are leaving ourselves exposed to our story being narrated by someone else. Telling our stories is empowering. Oftentimes when I think about that, I’m not thinking about the adults. I think about the children because there is such an impression that can be made when a child looks at images that celebrate them. You’re propping them up and to have that within a community, it does so much.

For my process, I see something that needs to be adjusted and I do a piece that responds to it. It’s a conversation against untruths that need to be corrected.

Mark “Feijão” Milligan II

Totally. I’ve heard you talk about the people in your life who you’ve painted or drawn. What do your muses think of your work? How do they respond to you? Or how do they respond to seeing themselves through you?

Everyone’s reaction is a little different, it’s never exactly the same. Sometimes I can tell they feel very flattered. Some say nothing. [Laughs] But in general, I’ve always had a good experience when I work with folks. Because I personally enjoy the process. I enjoy creating art where it’s collaborative, where I’m able to go to someone and we pose and we do these different things. I think the people have enjoyed it too.

Regarding the symbols that you use in your art, particularly foliage, water, the stars, what do they mean to you? Why incorporate these natural elements?

I love richness. For instance, with food, I love dishes that have a lot of different elements. One of my favorites growing up back home was callaloo. It’s not exactly the same, but one could compare it to gumbo because it’s this rich mix of the callaloo leaf and different meats and sometimes you even put a little fungi or fufu in there. It’s mixed, it’s layered. That’s kind of how I like to create my artwork. Very layered. A lot of what the symbolism really boils down to it is actually religious or spiritual. I find that icons already have, within our culture, been given a certain amount of weight. People have certain associations of the sun or the moon, regardless of where you’re from — that’s global, that’s almost genetic. When you see the sun, generally people will think of brilliance, wisdom, growth. If I want to bring in a different kind of vibe, maybe I’ll reference the moon, to create a sense of solitude and the wisdom associated with that. Oftentimes it’s about creating that right balance, you know?

Absolutely. How has your art evolved, shifted, or surprised you since living in Hawaiʻi?

I have not shifted my art a lot, but there’s a reasoning behind that. I did not want to come to the islands, not know about the culture, and start feeling like I can include all kinds of imagery, acting like I am in a place where I can start to speak for the Native Hawaiian culture. I take that very seriously. If I’m going to be a vehicle, I want there to be some kind of knowledge base there. I want there to be time. I intentionally have not tried to take on that kind of voice until recently with the mural Tapestry in 2020. I had this huge wall for Pow Wow Hawaii, it was the size of a tennis court. It was in the Salt complex at Kakaʻako and there was a connection with Kamehameha Schools too. I requested to have two students from KS join me and work on the wall together. I could almost mentor them throughout the process, and give back in a way that I remember being given back to when I was a child. I went to a teacher and I asked questions because I knew, in that instance, I wanted to create a piece that spoke to the Native experience. I wanted to use that public platform as a vehicle for that portrayal, but I did it with research and seeking permission.

That mural was already influenced by the foliage there too it seemed.

Oh, yeah, without question. A lot of what my experience has been living in Hawai‘i is seeing a strong connection between the West Indian and Caribbean experience in the environment. I’ll go out on the west side in Waiʻanae and be like, “Oh, that’s kasha (buckwheat).” Even the plumeria, we have plumeria back home, we just call it something different. So there’s so many connections and I do bring that to the pieces. For example, in Yeshua/Horus and Madonna/Isis, the foliage is Hawaiian. If you have the eye, like you do, you can see the connection, you can see that there’s a dialogue with the Hawaiian experience and the West Indian experience just through the inclusion of the foliage. That I definitely can do. There’s so many conversations that can be had there. The political connections, the experience of the Native Hawaiian culture here and the experience of us back home.

Can you be more specific? What do you mean by the experience?

I’m speaking to the experience of colonization. We’re both cultures that have histories of colonization. I think that’s one of the reasons why I also approach the culture with a certain reverence and respect because I know what it’s like to come from a culture where people colonize a place and bring their perspectives of who we need to be and impose that on us. Almost with like martial law. I know what it’s like. I come from St. Croix, which is the furthest east possession within the United States, Point Udall, as far as I know. Then to be here in the furthest west, there’s a whole dialogue there. And, so many different similarities, even the way that we speak. There’s a resurgence of ‘ōlelo Hawaiʻi, which I think is beautiful, taking on your language and taking it on with pride. Back home, we have different Creole. I come from a culture where we speak Cruzan and sometimes one would refrain from speaking it because it may not be the “proper” way to speak. I remember going to school and sometimes they would tell us not to speak Cruzan.

I’ve seen your artwork in so many different phases and I’ve just developed a new relationship with your artwork. What are you creating these days?

I did a really cool collaboration with Solomon Enos that left me very inspired. I always appreciated his work before, but to actually do a collaboration … we gave each other sketches and then completed them. So he completed a sketch that I did, I completed a sketch that he did. With something like that, you actually have to kind of get into the person’s mind a little bit. It’s like you starting a sentence and then me finishing it, but we actually did it without actually meeting each other. We were kind of familiar with each other — we had seen each other’s artwork — but we had not actually even had a conversation. So to have that kind of dialogue, you have to like, you know, do a little research, you have to get into their head. That was really inspiring for me because he’s an amazing artist, has an amazing portfolio — in actually working on his piece and completing it certain things kind of to re-bubble up within me. It had my mind thinking in different ways. A lot of what I’m gonna start working on now has threads of that experience in it. There’s a certain amount of surrealism in it, it is gonna have a little element of a native Hawaiian experience in it. I actually have models that are gonna be posing and there’s a new series that’s gonna be coming out of that.

Who are you inspired by or who are you looking forward to seeing grow? Anyone you want to shoutout or uplift.

I tend to be really inspired by my peers. One person that is really amazing is Jules Arthur. I don’t think I even tell him this that often, but he is an amazing artist. We actually went to school together and I just knew him more as a person. At school we would kind of pass each other by. He’s really warm and little did I know he is a genius. He is an amazing artist. Over the years from college to now, we continue to have some dialogue over social media. He is very inspiring to me personally. He might be actually surprised to hear that, but that’s the truth right there.

There’s some people that are really large that aren’t necessarily my peers like Kehinde Wiley. If I would like to be some place, I would love to be at a level where I’m working like Kehinde because he has really revolutionized the whole concept of what it means to be a Black artist. The way that he has been able to establish himself has been fantastic. He is just working with such high autonomy, it’s just amazing. Local artists, too, like I mentioned before Solomon Enos. His prolific ability, like, when you look at the breadth of his work and what he creates, he is able to do so much with the amount of detail he has in there.

La Vaughn Belle, she’s an artist from St. Croix. Seeing the way that she works with the narrative of the culture that we come from and then kind of references past historical instances. She just created this beautiful sculpture that was displayed in Northern Europe that is a dialogue between the West Indian and European cultures and colonization called I Am Queen Mary. It’s really beautiful to see the way that she’s growing within her artwork too.

Where can we find your art these days?

I just recently had, surprisingly, two of my pieces on national television. One was on NCIS: Hawaii. Another on Lizzo’s new show, Lizzo’s Watch Out for the Big Grrrls, one of my pieces is in that too. My work just recently got included in the personal collections of a couple substantial people. I’m gonna honor their privacy, I’m not gonna name names. But, you know, one is a former president of the United States of America. Another one is the current governor of the US Virgin Islands.

I love to hear that you’re being celebrated in the way that you should be celebrated. I love that your art is reaching the people who need to see it.

Thank you. I love what I do. I love the opportunity that I’m being given, our conversation, I love this. I just want to continue to grow and to better myself.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.