Contending with a pandemic that uprooted their livelihoods, Mitchell Kuga and Adam J. Kurtz settle in for a talk story on art, work-life balance, and creating a new island home.

Before moving to O‘ahu from New York in 2020, Mitchell Kuga and Adam J. Kurtz discussed what transitioning to Kuga’s birthplace could look like, but neither imagined living with parents for nine months in the house that Kuga grew up in. Still, the scenario proved to be a welcome respite with moments of surprising reconnections and newness that informed their solo projects. Both with books in the works, the creative couple aired their struggles and epiphanies about the creative process and artmaking in a pandemic.

MITCHELL KUGA There have been challenging moments to me about moving back. But I also think this time is really special in a lot of ways.

ADAM J. KURTZ This is how I feel. What’s the most surprising thing about coming back here as an adult?

M How comfortable I feel being myself in ways I didn’t before. Just how gay I can be, by which I mean just being myself. Part of that is having you here in my childhood home, where I often struggled to be myself in so many ways.

A It’s hard to be in the closet when your 6’2” white husband is following you around the island. All bets are off. And I feel like you dress a little differently. You act a little differently. But, actually, it feels more like you than ever. You’re just older.

M I’m just older. Before moving, we’ve come to Hawai‘i for the holidays every year for the past eight years. What do you remember about those first trips? I feel like you are not someone who came with many preconceived ideas about this place as a tropical paradise.

A [Laughs] I think when we met it was very important for you to teach me that Hawai‘i is not a postcard version. One of the early lessons was you making sure that I know Hawai‘i is not “pineapple surfboard.”

M Is that a type of surfboard?

A No, that’s shorthand for what most haoles think Hawai‘i is: pineapple, surfboard. Now they know about poke—eight years ago they didn’t know. Sometimes I do a full stop and I’m like: I. Live. In. Honolulu. And that’s insane. I laugh because I would never have come here if I didn’t meet you. It wasn’t on my radar. Actually, I’m glad to be here this way. I think it’s more meaningful to come here for the reason of love versus ‘Oh, it’s beautiful and I fell in love with the ocean, so I had to move here and I opened, you know, like a little shop in Kailua where I sell native style crafts but I’m white.’

M I mean, there’s still time for you.

A I would say, too, that your perception of what Hawai‘i is like, Honolulu specifically, is really different than what we’re experiencing. Your perception as a teenager was, ‘Oh this isn’t a place where I can be gay. I want to go to the mainland and find my own footing and be my own person.’

And, listen, this is not Brooklyn, but it’s actually pretty gay here. We see queer people everywhere. Not en masse and they’re not wearing Doc Martin boots and shorts like they would in Williamsburg. But they’re here at the Safeway deli counter and, you know, queer weirdos at the mall. We’re out here.

I think what I am really learning is that a lot of my understanding of Hawai‘i is through what I’ve heard from you. And what I’ve had to unlearn is that your perception of Hawai‘i is rooted in being a teenager here.

M Absolutely.

Kuga, a freelance writer, working from his childhood bed.

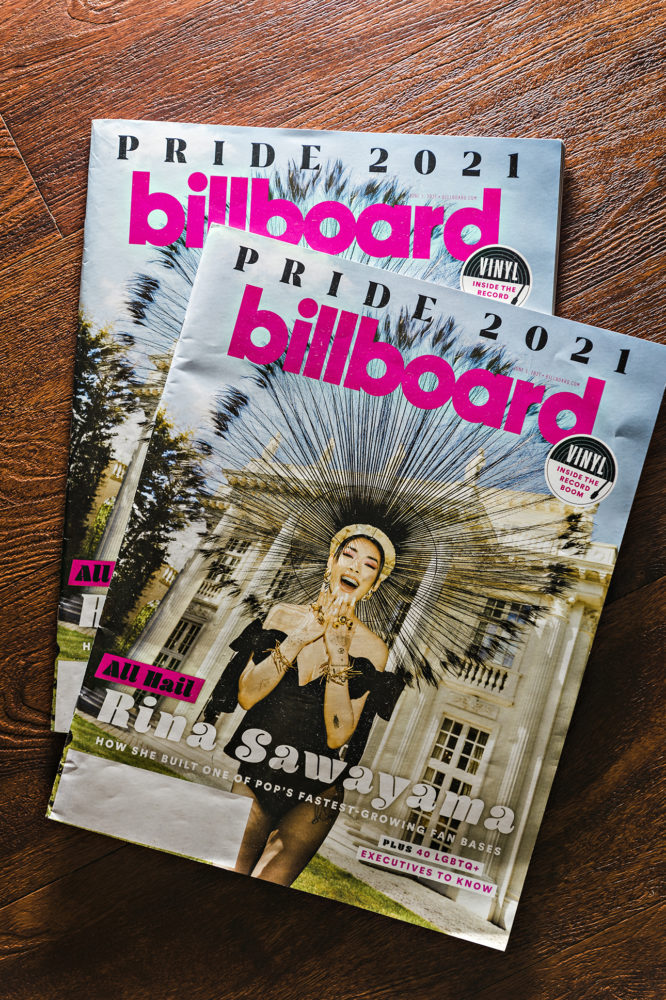

Despite the move, Kuga sustained his writing career, landing the cover piece in Billboard’s Pride issue.

A And being a teenager anywhere is going to have a very specific lens and worldview. And through annual visits I’ve glimpsed more and more of Hawai‘i and have come to my own understanding. It’s more inclusive, it’s more inviting. There’s more here than I think I realized. I’m also very excited because clearly the creative community here exists and is layered.

M From Toronto to Baltimore, you’ve lived in many different places throughout your life. How does this feel different from other transitions?

A Yeah, my family moved from Toronto to the U.S. But moving to New York was a choice. I wanted that, to be someone in the city. I really thought I was going to live and die in New York. And there’s a version of me that would be that person. But there’s also a very core version of myself, it’s the quiet voice at the end of the night in your head. That version of me knows that it’s good timing to be here. When I look back, I know I will be grateful it happened. It’s already been a catalyst for a lot of change. Moving here is encouraging me to do different kinds of changes. My work has shifted. My mental health has shifted. I’m feeling a calm I’ve never felt in my life. And that’s not necessarily Hawai‘i specific. It’s just like a simpler life, fewer distractions.

M Does that feel like it’s more about getting out of New York than it is about Hawai‘i specifically?

A It’s not even about getting out of New York. Sometimes you just need to change your place to change your luck. That is a Jewish saying that I think about a lot. It’s not about the city—a city doesn’t define you. But you often define yourself against the backdrop of where you are, and what you do, and who you know. When you take away those distractions, you’re left with who you actually are. Covid did that for so many of us; you couldn’t go outside. So, you were stuck inside, AKA stuck in your brain, AKA who are you? And what do you want? How much did Covid impact your decision to move home?

M It wasn’t everything, but it was a big part of it. Covid was the thing that sped it up, this inevitable thing that suddenly felt more urgent. It was a gut check for me. It raised a lot of big questions about what I was doing in New York and why I was doing it, and then weighing that against these other questions around my family and being here for my parents.

A Right, like what really matters.

When I look back on this transition, I know that I will be grateful that it happened. It’s already been a catalyst for a lot of change.

Adam J. Kurtz

M I knew in my heart of hearts I would have a hard time living with myself if something ever happened and I was not here. The pandemic put into perspective just time in general, how it’s not infinite. It forced me to think about it more wisely. Mortality and shit. I think a lot of the things I moved to New York for felt like they didn’t exist. But also those things weren’t making me happy anymore either. That kind of striving, the careerism, the game I feel like you learn to play in New York—it wasn’t super exciting anymore.

A What I always loved about you is you seem to be the rare New Yorker who enjoyed the parts that you liked about being there: the community and proximity to things. But it seemed like you were never doing anything that you didn’t want to do.

M I think there were a lot of projections when we met about who I was, things that you needed at the time.

A I really fell for your trick. That’s what a relationship is, yeah? We’re looking for people that complete us so that as a shared unit we can build and grow. I do think that you represent—objectively, big picture— a slowing down and I represent a speeding up. And we meet in the middle in this beautiful way. Both of us have grown our work and ourselves in different ways.

M How do you think living here has changed your work?

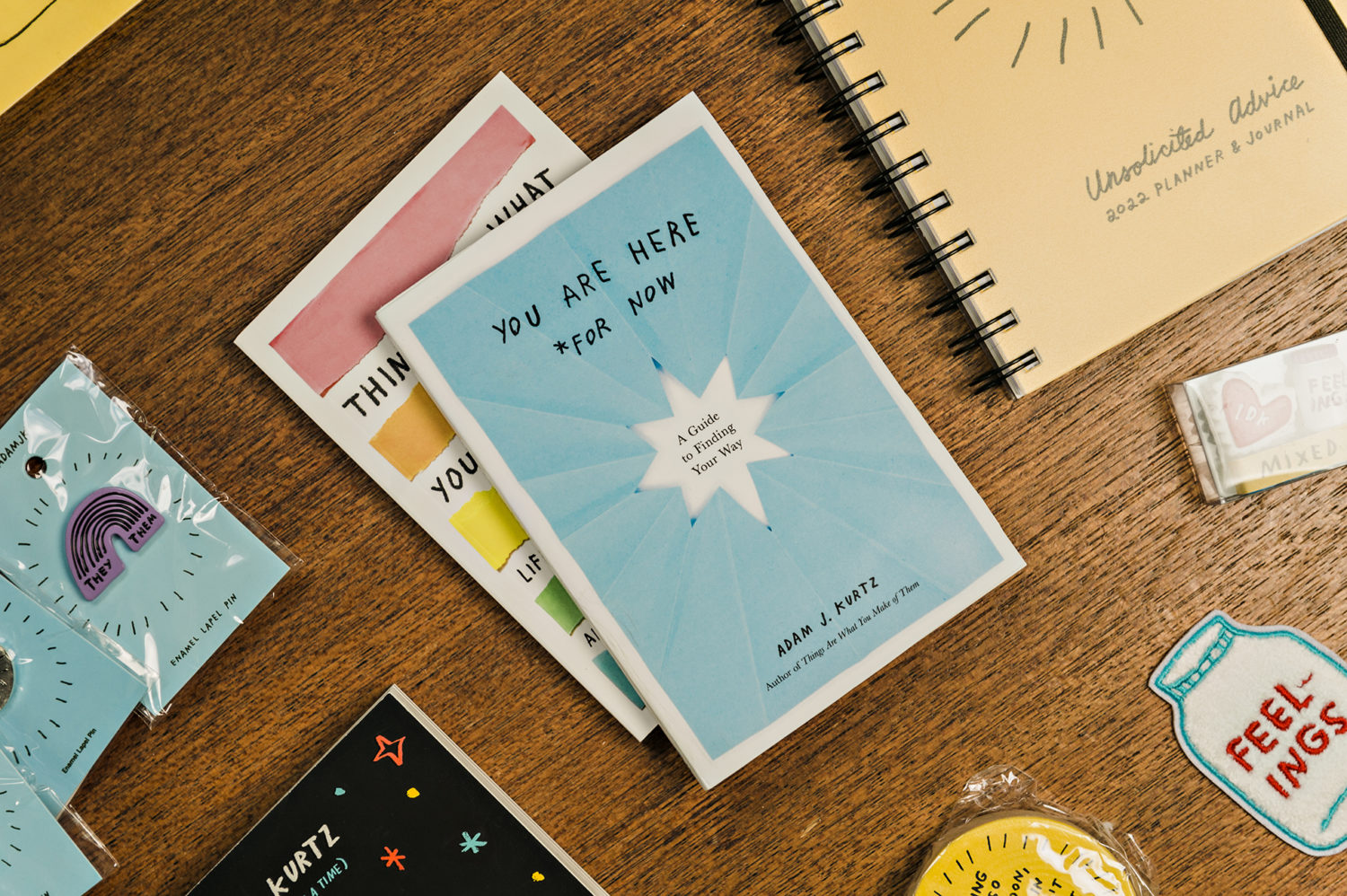

A In some ways, I don’t know the answer to that yet. But it has been a trip. It’s been interesting working from Mom and Dad’s house. I used to have a a cool studio space. And now, I basically made a book, a planner, merch and products in your sister’s childhood bedroom at her desk that I barely fit in.

M Inches from where we sleep.

A Exactly, at the foot of our bed. It’s almost like I’ve gone back to age 22 in my first New York apartment where I was working from a tiny desk next to my bed. And that’s a testament to the fact that it doesn’t take fancy stuff to work. You don’t need an artist studio to make art. You don’t need expensive tools. That’s very much at the ethos of what I believe anyway, but I had to live that again.

M To your point about creating work anywhere, in the beginning was there a sense that you couldn’t?

A Yeah, I just had to wrap my head around it. My work has always been pencil and paper. It started that way because that’s what I had and I couldn’t afford shit. You remember me in my little Brooklyn apartment? I was hand stapling my zines. My work started this way because that’s what I had access to. My parents aren’t rich. I didn’t go to art school. I relearned that you can just make anything out of anything, wherever. I wrote the rest of the book, You are Here for Now, sitting around the house. All the artwork was photographed on the folding table that I set up in this room. I’ve given several conference keynotes remotely by moving the bed over so I can stand in front of the wall. You just adapt. In a lot of ways it’s been very nice working small and working loose. The book is intentionally looser from a visual perspective, like the handwriting is less tight. The way that I scanned and even cleaned up the handwriting is more raw.

M Because of working in this space?

A I wanted it to feel really, really real. I wanted it to be like I am talking to you from as far as we’re sitting right now and I wanted it to be like I wrote you a note. I wanted it to be viscerally human. For the last year, you’ve been working on a book that is about you as a person born and raised in Hawai‘i. You as a queer person, as a queer Japanese person. It’s centered around this place, and in the midst of working on it you’ve moved home. Does that change the book’s trajectory?

M It feels like it completes the book in a lot of ways. Beforehand, it was a collection of essays about leaving Hawai‘i and figuring out who I was in New York. Even then, the idea was always that I would move back. But the book definitely wasn’t proposed as a return home because that wasn’t really in the cards, I thought, until at least the next five years.

So, moving home now changes a lot. It basically changes the whole last section of the book because now it’s about what it means to return. There’s a proposed chapter about pickleball and a chapter about starting a garden, both of which wouldn’t have been there previously. A lot of it is about the present, what we’re going through now. Before, it was a lot of looking back.

I wouldn’t say it’s given my life here purpose, but it makes it feel like I am in the process of writing and ideating stories as I’m living my life, which I don’t think is how I live my life typically. I don’t usually go through my day thinking of myself as having main character energy—the narrator of a story. It does feel like I’m living with a prompt in some way because I understand that this period of time, this transition, fits into a larger narrative I’m trying to write.

A What about being here is a reminder you absolutely made the right choice?

M Moments with my parents that feel really casual and nice. That don’t feel heightened by a sense of being on vacation, or of our imminent departure. Seeing them and their lives change as a result of us being here. And seeing your relationship with them, how that’s evolved, is really touching as well. It’s these really quiet moments, right?

A One really, very sweet thing is when they ask me questions about work. I was doing the photography for You are Here for Now in a little pop-up photo tent I bought online. Mom and Dad came to see what I was doing. That was cool and it meant a lot to me. I don’t know, I want to make them proud. I want them to be part of the process. My life is that I am this weirdo little artist who makes things, and it’s nice for them to see that firsthand.

M In some ways, this book feels kind of like a product of our move because—speaking to the actual production of it and having to make those changes—in New York, prepandemic, you probably would have hired a photographer. But beyond the constraints of Covid, there’s the actual transition as it relates to the content and the emotional core of the book. In what ways has living here changed the book?

A It became a book about not waiting for permission, but just making the things that you needed. That happened because of our move. My editor and I talked about changing it just a few days before we left New York and just had this moment of: I think the book is not the same book anymore. I’m leaving and life is different. The urgency came as a product of this move and realizing I need to take my own advice.

In the time since getting here, I wrote the second half of the book in the house. The clarity of being here helped inform a lot of the more hopeful parts of the book, but also made me feel finally comfortable enough to be extremely vulnerable. I don’t think I was planning on talking about wanting to kill myself. It was not originally a book about suicidal ideation. Then, to feel so safe and comfortable—I am far enough away from that scary time that I can talk about it in service of helping others.

Being in Hawai‘i, extracted from what my was life in 2019 and sort of plopped down in a new life, gives me a lot of comfort. And feel the most connected to you I’ve ever felt. I’m not alone, I have this family and they support me.

M Living here has really brought that concept of family and love to the forefront. I feel like we both understood it as a philosophy, but I think living here together really feels like a new rung of that idea because of the level of dependence in some ways.

A And trust.

M I think anyone familiar with your work will notice throughout the book there are these mantras you previously printed on mugs or T-shirts. It feels like you’re taking these broad themes, picking them apart, and diving into what they mean exactly.

A Fans of my work who are really in on it with me sort of understood the connection between it all, but there’s also thousands of people who bought a popular keychain from me, and they don’t have a context for how it fits into who I actually am as a person. This book really ties it all together. This is the hopeful, flawed, mentally ill person that this all comes from, who is really coping and communicating in any way that they can. That’s what’s scary about making this book but that’s also what’s so exciting—to say, that thing that you love that’s in your home, this is where it came from. This was the intention. I feel like the book that you’re working on is sort of your own breadcrumb trail that forced you to really dig into your previous understanding of what you thought being a gay Asian American person in Hawai‘i is, and then brought you back to it. It’s this tether between who you were, who you are, and who you could be next.

M I feel like every good essay is always trying to show that distance between who you thought you were versus who you actually are or who you’ve become. I moved to New York 14 years ago for college because I didn’t think I could live in Hawai’i anymore. A decade later this place I left felt bigger and bigger in my life in a way that became unavoidable. There’s such a clear arc there between who I was and who I’ve become. The things that happened along the way that allowed me to feel like home was not about a city so much as living in my body, creating a home in my own body.

A We’re both these artists-types that process our lives through the creation of work, translating our emotional reality into something tactile. Each of our books that we’re working on during this time helped us deal with this big life change.

M Something that we talk about a lot is work-life balance…

A [Laughs] Why are you attacking me like this?

M Well, I think we are both people who tend to over-identify with their work in some ways. Do you think your work-life balance has changed?

A One thing I’m excited about is the show at Bās Bookshop launching at First Friday on November 5th and will be up through February. I’m very excited about it because it is creative work that I’m doing but it’s not really for sale. I’m just making art to make art and it feels like it is entwined with my life in a new way. It’s basically me introducing myself to Hawai‘i’s creative community in a very literal way.

It’s cool to have that opportunity because I’m new here. I want to find my way in this creative community. I want to connect, and I want to make things. I want those things to be an extension of me, as an opportunity to introduce myself as a person who now lives here too. It’s not like I’m a special guest from New York just here for Christmas doing a pop-up shop. This is like no, I’m here and hello.