The sinewy, cerebral paintings of Roland Longstreet reflect an active and brainy creative process from the Honolulu-based artist.

Roland Longstreet sounds like he is on the artist’s path when he tells me, “Just making work is where I’m trying to be mentally.” In October 2020, Longstreet procured a studio residency with Single Double, a boutique for chic, vintage island goods on Nu‘uanu Avenue in Chinatown. Coveted by artists, residencies provide what daily life cannot: time and space to work through ideas.

This residency, Longstreet’s first, is a challenge to his commitment.

“I know that I’m trying to scrape at something there’s no manual for,” says Longstreet, “It’s not like step one, step two, step three. I make own steps in my head. But it’s an experience I’m exploring for myself for the first time.”

Longstreet stands medium lanky, wearing a draftsman’s apron. Buoyant locks of hair top a friendly but often pensive face.

After 10 years consumed by managing Ars Cafe, the coffeeshop-art gallery space near Waikīkī, he jumped into the art world in December 2019. He now installs art for corporate clients and others. In the Chinatown space, though, he is making time to paint.

The studio has a wide glass storefront and a loft in back. Nearly every inch of the room features his wet-looking, gestural figure drawings and paintings.

For Longstreet, the availability of walls, surfaces, and supplies is reason to paint as much as possible. Curious pedestrians can watch him do so from the sidewalk.

Image by Chris Rohrer

Image by Chris Rohrer

“If I stop myself from doing anything, it’s not going to go anywhere,” he says. “If I just keep making work, then that’s the work I maybe one day can destroy. Because it all sucks. But I’ll have done that to the point where I can make work that I think is good.”

Logical deduction. So how does Longstreet start?

“I gotta get loose and try to make a mess,” Longstreet says. “Because for me that’s a big part of it. That sounds obvious, but if I’m too timid about making a mess, then I’m not going to be able to start anything worthy of spending time on.”

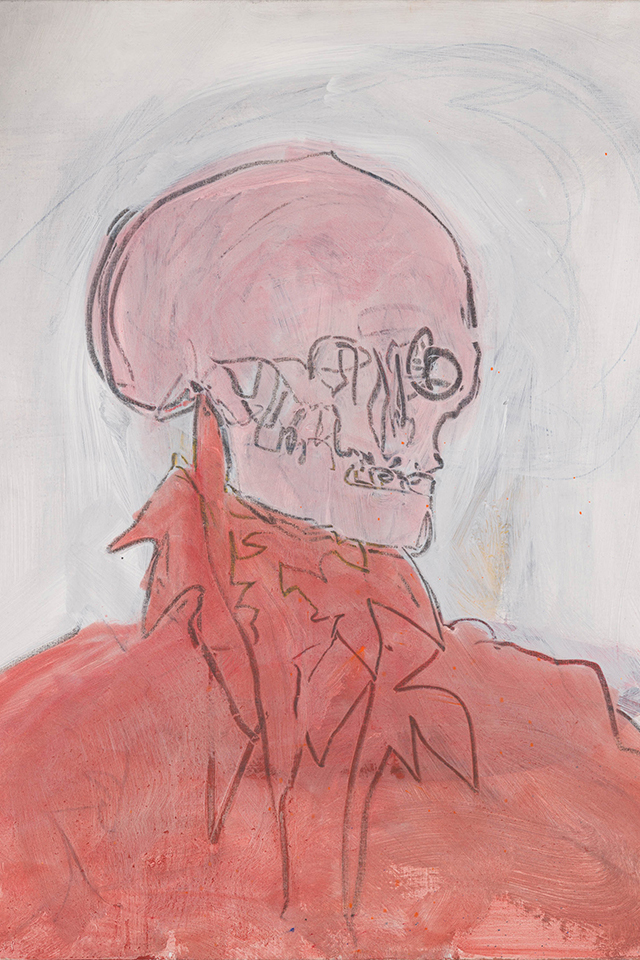

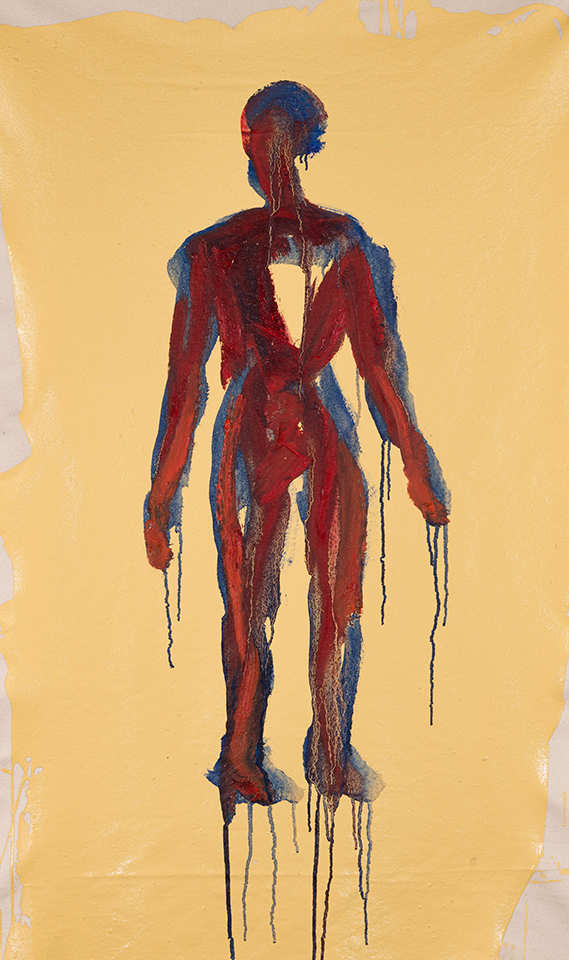

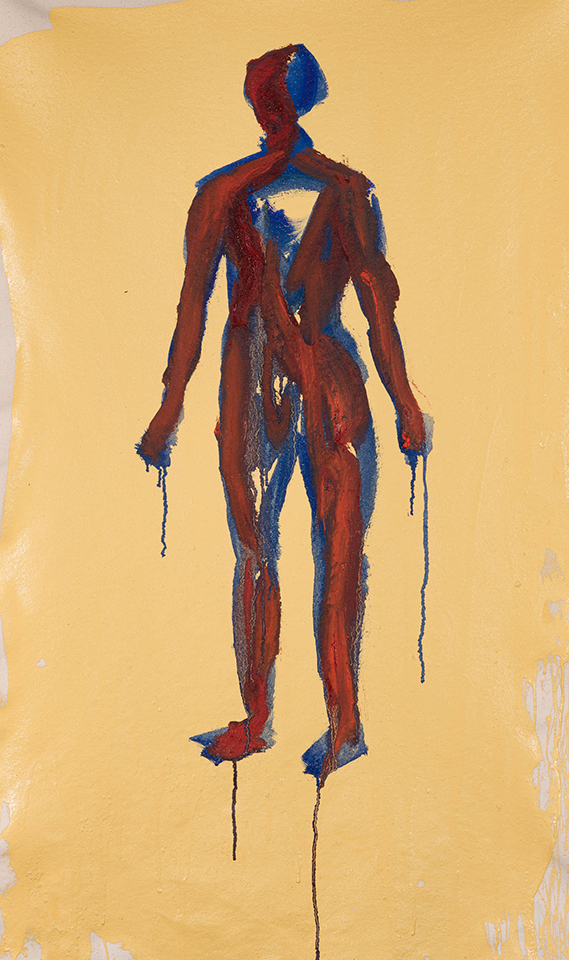

For Longstreet, the process involves sketching with large brushes and gobs of red ochre, blue, orange, green, brown, white, and flesh-colored paint. Muscly brushstrokes sweep through the colors, blending them al fresco. A tangle of strokes and colors become a face, a head, a torso.

“If I’m in the mode of being able to make a mess and use any material at my disposal, then I’m in the mode I should be, starting to paint.”

Image by Chris Rohrer

Image by Chris Rohrer

Longstreet has a bachelor’s degree in art with a focus on sculpture and painting from the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa. He says he was one of those for whom the word “paintings” meant Renaissance art and the Impressionism.

Recently, he’s been diving into the Abstract Expressionists, those American bad boys of the 1950s: Pollock, de Kooning, Gottlieb, Rothko, Motherwell.

Working large, for them the canvas is a record of heroic actions involving bold sweeps, pours, stains, spatters or interwoven drips of paint. Sometimes with dense activity, other times through expansive fields of color, the Abstract Expressionists removed recognizable subject matter and went straight for the phenomenological jugular.

“When I read into what they were trying to do, they were all a bunch of bad asses doing things that were never done before,” he says. “It seemed like they were trying to express the spiritual through abstract images, in a way where the viewer can feel the impact of what they’re doing.”

Their objective impressed Longstreet: to affect viewers viscerally, on a level above or below rational thought. “It made me look at my work differently,” he says. “It made me realize there are some similar veins. But I put the figure back into the composition, whereas they took everything out.”

Image by Mark Kushimi

Image by Mark Kushimi

He points to other more contemporary abstract expressionist figures by Francis Bacon. There’s definitely a resemblance.

Four small studies lie on a table. Paint, brushstrokes, and erasures writhe in the shape of a head. They’re largely all the same colors—olive, red ochre, pink, and grey—but each one gives off a distinctly different vibe. Longstreet is looking for the version that feels most alive.

“I’m going to be 31 this year,” Longstreet says. “It’s an ever-present sense of dissatisfaction with how much I’ve made or even the quality of the things I’ve made so far. When that gets pent up, eventually it makes me eliminate everything else and get here and make.”

Longstreet points out that an errand at Longs can derail the whole thing. Forget lunch with friends, food shopping, or a lazy morning scrolling through Instagram.

“That’s all it takes and you’re not in the studio,” he says. “I realized I was so fed up with the fact that I didn’t make much, so I spent seven hours in here. The next day I did the same thing. I felt great. I felt fantastic.”

Longstreet flips through a pile of newsprint figure sketches. There’s a line drawing, another features gestural swipes using the side of a conte crayon, wax pencil cuts through gouache in another drawing.

On one page, dry brushstrokes criss cross the surface insistently, and a sinewy person emerges.

“That’s what it takes. The elimination of everything else in order to do this.”

Longstreet is gunning for a fuller figure now, life size or larger. Painting is his only way out.