Artist Kaori Ukaji incorporates the most personal objects and internal inspirations into her work.

Kaori Ukaji’s home is an exercise in eclectic, artistic delight. A colorful woven rug is splayed across the floor, and a merry assortment of tchotchkes invites inspection. Paintings, sketches, and photographs texture the space with a well-worn cheeriness, while a spherical, metal-wire ovum nearly 5 feet in diameter, created by Stephen Lang, Ukaji’s husband and fellow artist, hangs over the seating area.

Across the room, a glass jar featuring stratums of wooly material also begs inquiry: It is fur collected from Umi, the couple’s dog. Nearby, a low-lying apothecary dresser showcases nearly 40 miniature compartments, each retrofitted with a brightly patterned enamel knob.

Neatly penned labels designate the contents within: Sandpaper. Sunblock. Chalk. Two drawers, one atop the other, offer more cryptic labeling: Things. Things Spill. Ukaji chuckles before offering a lighthearted yet similarly oblique explanation.

“You have things … and then sometimes those things spill over.”

Intentionally or not, Ukaji refrains from divulging the drawers’ treasures.

A Hawai‘i Island-based artist, Ukaji is both private and pleasant. Originally from Japan, she describes having a quiet and responsible childhood, when a daily routine of school, piano lessons, and afternoons spent drawing and crafting paper dolls offered sweet contentment. She was especially fond of tracing paper, with its silky, onion skin sheets, and the dot matrix printer paper—with its accordion-like continuity—that her grandmother brought home in reams from her government job. (Such inclination toward paper’s tactility and form would emerge as a leitmotif in Ukaji’s art years later.)

By high school, Ukaji’s affinity for art had sharpened to a focus. Hewing to her father’s pragmatic advice of “getting a skill in hand,” she listed “designer” as her chosen career path in her high school yearbook. Upon graduating from college as a trained graphic designer, Ukaji settled into the professional world as an artist in Tokyo.

“You have things … and then sometimes those things spill over.”

But at age 30, Ukaji felt an unmistakable urge to fly on. Leaving Japan and her position as a research associate in Musashino Art University’s graphic design department, she embarked upon a year of travel. The journey was summarily cut short.

“Although I had never been here before, somehow, arriving in Hilo made me feel that I came back,” Ukaji recalls of landing in Hawai‘i. “My feeling here [was] so deep, I could not leave.” A mysterious power compelled her to stay, and over the next 20 years, Ukaji’s art came to reflect her enigmatic interior, echoing the ever-changing susurrations of self.

If Ukaji’s art is a barometer of her internal state, her ear serves as the bridge to that inner sanctum. To Ukaji, the ear is most sacred.

“I go almost into a trance,” Ukaji says of the rhapsodic feelings that surface when she gently touches the sensitive areas of her inner ear with a slender pick. Ritual exploration of her ear allows her to tap into a sensual, mystical existence. This is her mandala, a glimpse into the entirety of her being and the inner ecstasy that resonates there. Drawing on that energy, Ukaji then translates it into her art.

For years, Ukaji’s pieces focused on graphite, paper, the color black, and straight lines—symbolic representations of the tightness and strength she felt within. But as years passed, her inner world softened, and so, too, did the lines of her art. In the early 2000s, a keen interest in other materials rose to include her own skin, hair, and ear wax.

Like the exploration of her ear, canvassing her body became a daily ritual for Ukaji, and she felt no hesitation in subsequently using the skin and hair she collected in her art. For Ukaji, it was a statement both pragmatic and profound: Using elements of her body in her art was a natural extension of herself. Around that time, Ukaji also found herself pulled to another powerful color: red.

“Black is me, but red is me, too,” Ukaji says. When she married Lang 15 years ago, Ukaji became drawn to true red; today she describes the color as having evolved to a red-orange hue, like blood exposed to air.

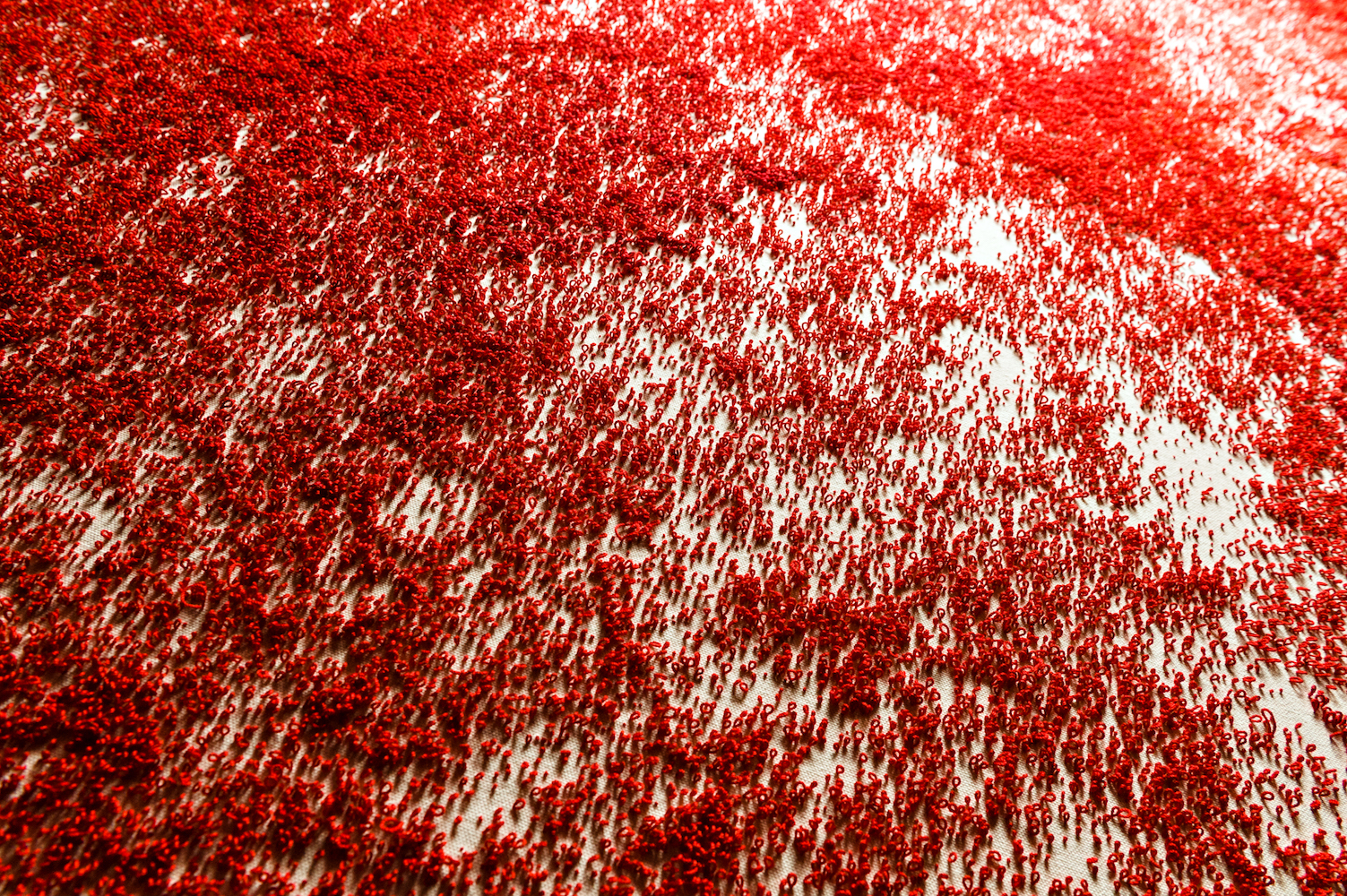

This red-orange hue was present in Serenely Proliferating, Ukaji’s installation for Artists of Hawai‘i 2017 at the Honolulu Museum of Art. She fell into a meditative state during its construction, as she had with pieces in the past, prompted by deep concentration and the repetitive movement of her hands. She imagined the artworks as a metaphysical journey through her body, to be intrinsically felt as much as seen.

“It’s like something slowly spreading,” Ukaji explains of the feminine mystique—a concept of womanhood she is exploring—that is emerging from the art. Crimson is diffused among lush, cylindrical folds of white bath tissue. Large, hanging embroidered canvases, their fronts and backs exposed, display the delicate recursive stitching of thousands upon thousands of thread loops. Two works, created with skin she peeled from calluses on her feet and then dyed a rich orange-red, are exquisite, organic interplays of matter and interstice. For Ukaji, each piece in Serenely Proliferating is a rapturous hymn to her body. “I only make pieces of what I am now,” she says.

Back at home, the apothecary dresser silently holds its cache of treasures. Sewing. Graphite. Glue. The contents of Things and Things Spill remain wondrous and unrevealed. Sitting near the dresser, Ukaji speaks of her art as an embodiment of self, a suffusion of her ever-evolving identity.

“Always my feeling is my art, always myself is my art,” she says. Ukaji has discovered a new energy that may soon be influencing her work: “It is like a river flowing someplace without my decision,” she says of the quietly expanding feelings and changes occurring within her. They swell up and in and around, waiting, perhaps, to spill over.

For more information, visit kaoriukaji.com.