Images by Christian Cook

A library of rare books on Kaua‘i represents a wide range of musings and curiosities about the natural world spanning five centuries.

The glass-enclosed rare book room is the first thing you see upon entering the National Tropical Botanical Garden’s research center in Kalāheo, Kaua‘i. Recessed lighting beams down onto bookshelves, giving the space an ethereal glow. “It was meant to be the jewel of the building,” says Tim Flynn, the herbarium collections manager. Like most of the staff here, he relishes any opportunity to browse its arcane stacks.

The little library of 600 titles includes rare monographs, accounts of sailing expeditions, and early editions of Darwin’s On the Origin of Species. The collection is especially strong in 18th and 19th century botanical literature. It once belonged to Elizabeth Loy McCandless Marks, who amassed it over the course of her life with help from esteemed botanists Joseph Rock and Horace Clay. The garden acquired the books in 1998, a few years after Marks’ death.

“When we got this collection, we promised we’d house it appropriately,” Flynn says.

To do so, the garden sought out renowned architect Vladimir Ossipoff, who provided the plans for a building that would honor the books and serve as a state-of-the-art research center. Completed in 2008, the building was the first on Kaua‘i to receive LEED Gold certification.

A paragon of modern design, the two-story concrete structure blends beauty and function. Photovoltaic panels on the roof generate electricity and a 25,000-gallon cistern collects rainwater.

The hurricane-proof facility houses the institution’s seed bank, laboratories, herbarium, research library, and, of course, its rare-book collection.

A treasure within a treasure, the rare book room is kept several degrees cooler and drier than the rest of the building. A halon fire suppression system protects its precious contents. A box of white gloves sits on a desk, available to guests who wish to handle the books. The library’s visitors tend to be scientists or artists seeking fresh inspiration.

“Tattoo artists spend hours in here,” Flynn says.

The oldest book in the collection is the hefty, leather-bound Herbolario Volgare, published in 1522. It is a compilation of folk remedies written in Renaissance Italian.

Simple wood-block illustrations extol the properties of meliloto (sweet clover) and cicoare (chicory). It is not a reproduction—these are the actual pages that a printer painstakingly inked almost 500 years ago, not long after Copernicus first proclaimed the sun the center of the universe.

On the nearby shelves are antique floras (regional botanical records) that specify what once grew in the wilds of Scotland, Syria, Japan, and Korea. The 1893 Avifauna of Laysan and the Neighbouring Islands describes and depicts now-extinct birds such as the Laysan crake in great detail. An immaculate copy of Isabella Sinclair’s Indigenous Flowers of the Hawaiian Islands lays open on a table. Published in 1885, Sinclair’s gorgeous illustrations were among the first artistic renderings of Hawai‘i’s native plants.

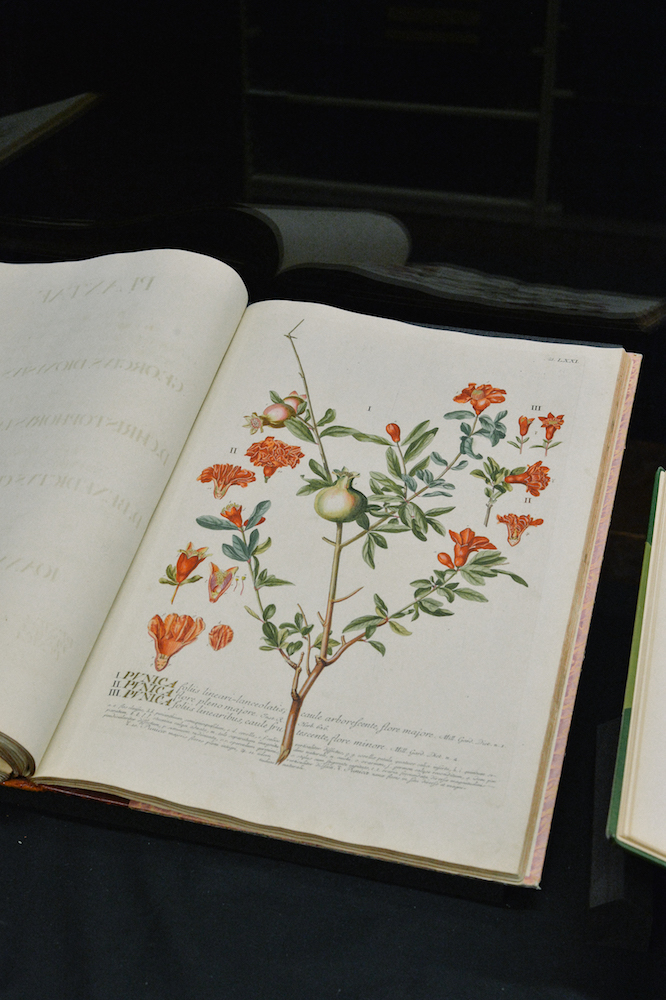

Some of the most exquisite botanical artwork can be found in Banks’ Florilegium, which occupies most of the shelves along one wall.

This impressive 35-volume set is a newer publication, though its contents date back to Captain James Cook’s first major voyage. Sir Joseph Banks was a botanist who traveled aboard the Endeavour with Cook from 1768 to 1771. Banks collected tens of thousands of plant specimens during visits to Madeira, Java, Australia, and Tierra del Fuego. An onboard artist created 743 paintings of these species, which Banks later turned into copper-plate engravings. The plates languished for two centuries before being published in 1980. Only 116 sets were created, including this one.

Several books on the shelves are handmade single editions.

“This is probably a one-of-a-kind,” Flynn says, gently flipping open a thin volume entitled Ferns of Hawaii. It’s by celebrated 19th century botanist William Hillebrand. Each page includes a pressed fern. Another novelty is devoted entirely to seaweeds.

One of Flynn’s favorite books contains delicate cut-paper illustrations by French artist Victorien Battandier. In flowery French script, its introduction reads, “Although the study of nature is of widespread appeal, not everyone approaches it in the same way.”

The rare book room isn’t the largest or most valuable botanical library in the world, or even in Hawai‘i.

But it represents a wide range of musings about the natural world spanning five centuries. Its intimate shelves hold the records of explorers, mapmakers, painters, poets, and plant collectors—the sort of curious people who slip seeds and leaves into their pockets to study later.

This ran in our “explore” section, click to read the other stories: An Upstream Battle and Deconstructing Statues.