Text and images by Joshua Iwi Lake

In the spring of 2010, I stood ankle-deep in colorful wires that lay in twisted piles on the floor of KGMB studio’s master control room. The oldest surviving television station in Hawai‘i, KGMB had hosted many locally produced programs, including Hawaii’s Superkids, Hawaiian Moving Company, Rap Reiplinger’s Rap’s Hawaii, and Checkers and Pogo. But this station that had provided Hawai‘i families with authentic local programming for more than 50 years had finally succumbed to the realities of an internet world, merging with local stations KFVE and KHNL a few months earlier. It was relocating to a new shared home in Kalihi, and what was left of its former location was a maze of lifeless rooms filled with boxes, old furniture, and forgotten technology.

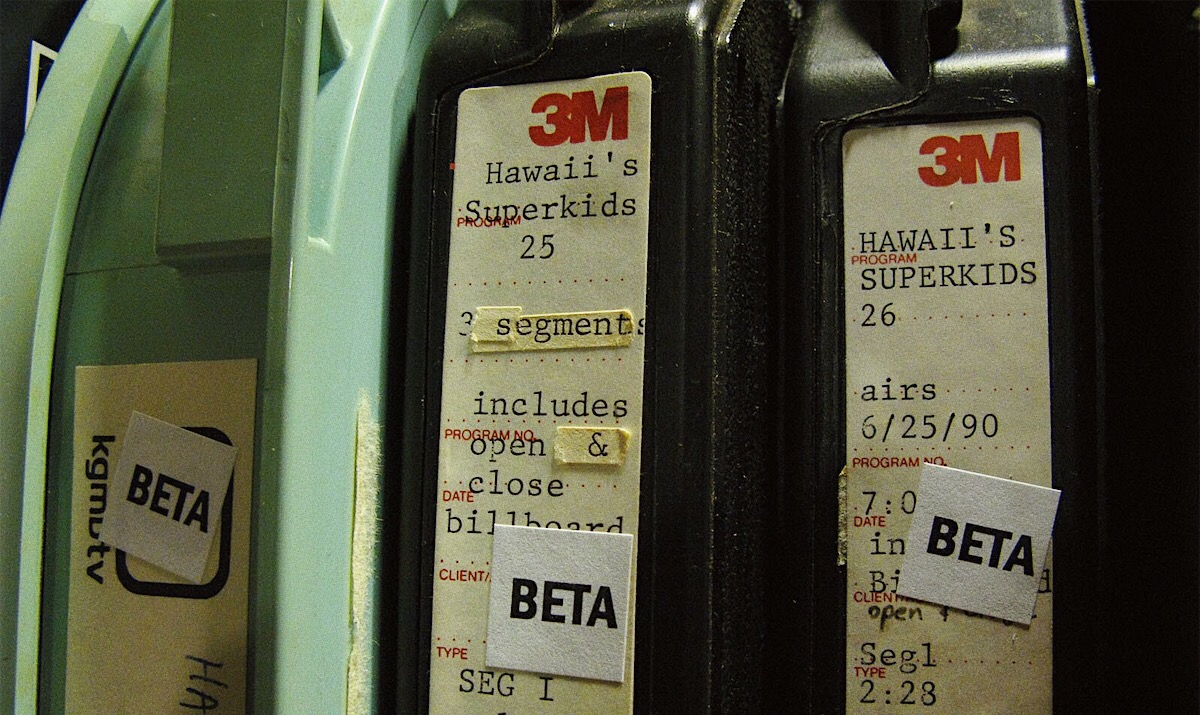

As I wandered the empty offices and hallways with Mike May, a friend and former KGMB news cameraman, we found one room that stood out from the rest: a small office space lined with mismatched bookshelves and oddly shaped boxes. It was the tape room. Typical of television studios, this room was a climate-controlled space that held broadcast-ready versions of programs and any reusable raw footage. Typewritten labels on cases denoted episodes of Hawaii Superkids, Hawaiian Moving Company, and nightly newscasts.

All KGMB legacy media, including these film reels, was to be donated and digitized at the Henry Ku‘ualoha Giugni Moving Image Archive of Hawai‘i at the University of Hawai‘i’s West O‘ahu campus, part of plans to protect KGMB’s archives and make it available to future generations. This is important because newspapers, radio stations, and local television outlets like KGMB build bodies of work that preserve the history of a place and its people in perpetuity. Analog technology has portrayed our communities through stories, photographs, news segments, and children’s television shows, and we are the beneficiaries.

Unfortunately, all technology is not created equal for doing so. For example, prior to the 1980s, almost all of the station’s content was shot on 16mm film. To reduce production costs demanded by the film, the station transferred its back catalog into newly emerging videotape technology and sent the original film to the city dump. But the videotapes deteriorated until they were unplayable.

As these institutions disappear, we trade antiquated trappings of ink on paper and light on film for still newer technology like Facebook posts and live television for Twitter updates. In doing so, we begin to undermine the archival services these legacy institutions provide. It is unknown if our investment in the internet and social media is building something similar. Our collective data represents who we are as a community and a culture. Without proper access to our shared stories, memories, and hopes, we undermine our own identities and self-determination.

According to Sree Sreenivasan, a technology journalist who served as chief digital officer for the Metropolitan Museum of Art and New York City, archives are a huge part of history. It is important to have an accurate historical record of everything and being able to access such archives enables this. However, paywalls, poor website design, and disregard for how the internet works have contributed to the demise of legacy institutions that generate this information even as they have attempted to go online. Furthermore, Sreenivasan continued, online platforms and individuals increasingly store everything digitally with cloud computing. “What happens if we lose access to the cloud?” Sreenivasan said to me during a phone conversation. “Everything’s in the cloud, great, but what if the cloud is gone one day? What would happen to all the collected memory that we have?”

This scenario is more common than we think. In 2012, Twitter went down for a few hours, costing advertisers an estimated loss of $25 million per minute. In 2015, Facebook caused self-inflicted downtime for nearly an hour, sending the website, apps, and dependent services like Instagram and Tinder grinding to a halt. These websites affect billions of internet users. Then consider the hypothetical downtime of internet service providers, domain registrars and website hosts, government and education services, and the millions of websites that depend upon them. We may have traded our boring but stable solutions for a virtual house of cards.

The internet also has another flaw. “You know the old adage, ‘History is told by the winner?’ In this case, history may be told by the hacker,” Sreenivasan said. “Many years ago, the front page of the New York Times was hacked. … But that kind of vandalism you can tell has happened. What is much more insidious [is if hackers] go in and change the [earned run average] of a pitcher from a baseball game of the ’40s or ’50s. No one would ever notice or check those records. That kind of tampering is huge.”

Hawai‘i, with its over-dependence on importation that has normalized out-of-state purchasing decisions and influenced our internet habits, stands to lose the most from a rapid adoption of cloud-based services and increasing reliance on social media as an archival tool. The state’s investment in social media and internet web services place the majority of the data generated by its residents in servers on the mainland and beyond.

Hawai‘i, with its over-dependence on importation that has normalized out-of-state purchasing decisions and influenced our internet habits, stands to lose the most from a rapid adoption of cloud-based services and increasing reliance on social media as an archival tool. The state’s investment in social media and internet web services place the majority of the data generated by its residents in servers on the mainland and beyond.

There is no local version of Google, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, or YouTube, and likely never will be. The idea of instant connectivity in your pocket is a highly effective illusion that only exists if the islands’ power stays on. This issue gets increasingly dystopian when you consider nearly every popular service is a publicly traded company that sells your data for profit. Do we trust these companies to protect our heritage and keep our memories safe forever? Can we verify our data hasn’t been tampered with? Will there be anything to show to future generations?