As modern society struggles with the postcolonial influences of the past, Hawai‘i’s statues continue to educate and interrogate their own relevance.

The accomplished explorer and cartographer Captain James Cook is widely recognized for providing detailed maps of the Pacific, including New Zealand, Australia, and Hawai‘i. His voyages to survey uncharted waters and strange lands for the British Royal Navy have placed him in a historical pantheon of contributors who mapped the planet. According to the Captain Cook Society website, an online resource devoted to his life’s work, there are more than 100 monuments dedicated to Cook around the world.

Landing markers and statues of the famous explorer dot Pacific coastlines, from the icy Alaskan Cook Inlet named in his honor to coastal towns of New Zealand. However, if you ask a Native Hawaiian about the famed explorer, you will likely be told of the monument located at the place of his death. On Hawai‘i Island, a solitary white obelisk on the shore of Kealakekua Bay marks Cook’s final stop. It was here, in response to the captain’s attempted kidnapping of the ruling chief Kalaniʻōpuʻu, that he was attacked and killed by natives defending their ali‘i.

Harbingers of Colonization

History books frame Cook as a benevolent explorer bringing modernity and order to the unknown world. Hawai‘i is often a sad footnote carved into monuments honoring his achievements: Killed in Ohwayee. Largely unmentioned in books and on plaques are the tragic consequences of Western sailors entering the Pacific. Cook and his crew were the harbingers of colonization.

Diseases such as chicken pox, polio, and tuberculosis quickly spread after they arrived, killing thousands of Hawaiians within two years of contact. Australia’s indigenous peoples faced a similar fate, as Cook’s “discovery” of the southern continent fueled a land rush by European settlers that brought devastating disease and violence.

On Hawai‘i Island, a solitary white obelisk on the shore of Kealakekua Bay marks Cook’s final stop.

Now, 250 years after his first voyage to the Pacific, Cook is under attack again. In anticipation of Australia Day in January, a national holiday celebrating the first British settlers, statues of Cook in the capital city of Melbourne have been repeatedly defaced. The words “change the date” and “no pride in genocide” were sprayed across statue bases in 2017, and “no pride” on one in 2018, reminding Australians of their country’s contentious history.

In the coastal city of Gisborne, New Zealand, a statue of Cook was vandalized in protest of his violent confrontation with the Māori, New Zealand’s indigenous people. In October 2018, the city’s council voted to remove the statue and place it in a museum.

For those who have benefited from the colonial occupation of the Pacific nations, Captain Cook is a historical figure worth remembering. But for those whose ancestors suffered after his arrival, his statues are two-ton physical reminders of pain worth forgetting. United States history is facing a similar reckoning as young Americans target Confederate statues that glorify the country’s racist past. In the summer of 2017 in Charlottesville, Virginia, a statue of General Robert E. Lee, a Confederate icon, was at the center of a violent protest at which a white nationalist drove his car into a crowd of demonstrators, killing one woman. Controversial statues across the country have been protested as historically inaccurate and symbols of latent racism condoned by their communities.

“Who controls the past controls the future, who controls the present controls the past,” reads a famous passage from 1984, George Orwell’s dystopian novel of a society plagued by war, propaganda, and government surveillance.

This statement suggests the motivation of many in scrutinizing the solitary figures standing in parks and at universities. From monarchs and religious figures to dictators and military leaders, statues are often omnipresent proxies watching over citizens and followers. In time, statues inevitably outlive their creators and intended communities and are left to the interpretations of a new generation.

Who controls the past controls the future, who controls the present controls the past.

To Hawaiian artist and sculptor Kazu Kauinana, the intentions behind statues are more altruistic than diabolical. “Statues are a way to pass on messages, ideas, or standards of what a person accomplished,” he says. “It’s a person’s life being honored, a righteous person, what they contributed, but times change.” In Australia’s case, Cook’s achievements are undeniable, but his continued presence carries a different message today. “That’s the failing of a statue,” Kauinana says.

“It captures a person who was considered incredible from that time. Kamehameha was a brilliant man and warrior, but by today’s standards, our own ali‘i were brutal. Things are relative.”

Changing attitudes toward statues are nothing new. Failed states, from the Soviet Union to Libya, have left behind an inventory of fallen leaders. As monuments, statues are erected to celebrate or remember people or events, but as memorials, they stand as somber reminders. Inspirational to one generation and controversial to another, a statue’s relevance is destined to change given time.

“The only statues that have real permanence are not related to personality,” Kauinana says. “We’re all human and being human means vulnerability. My favorite statue is the Statue of Liberty. It represents an idea, liberty, which never really changes.”

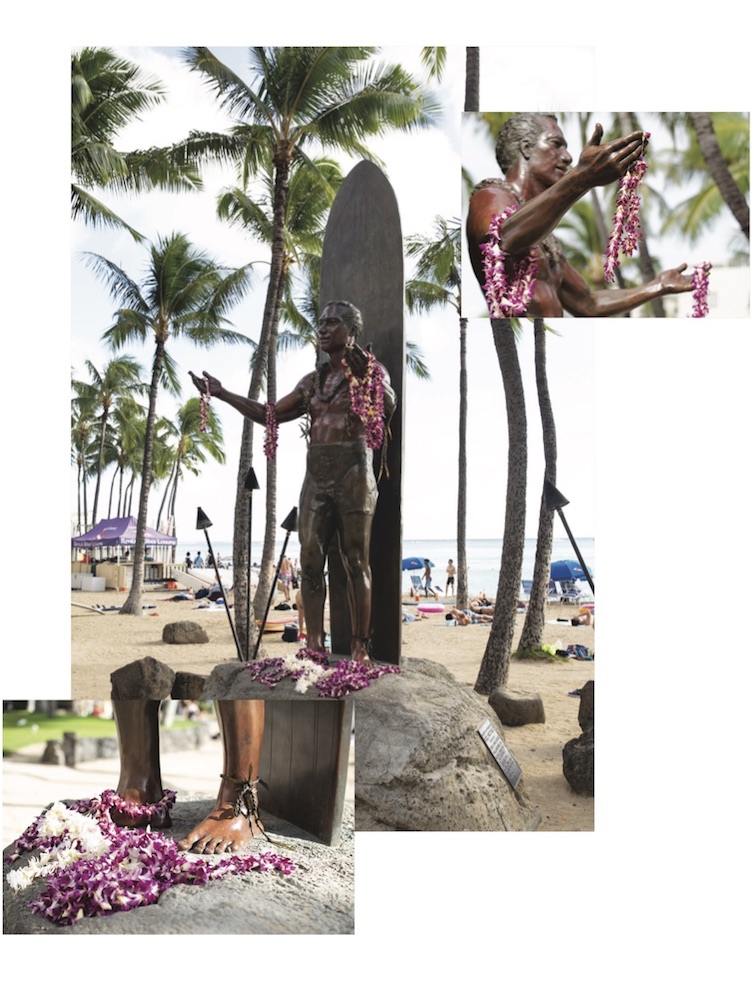

As the long reach of colonial influence slowly recedes, new statues continue to be erected for future generations. In Gujarat, India, a nearly 600-foot-tall bronze statue of Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, an activist for India’s independence from British rule and an advocate for the country’s unification, was completed in October 2018. In Hawai‘i, a 12-foot-tall statue of King Kamehameha III was unveiled on July 31, 2018 in Thomas Square Park to commemorate his unwavering commitment to sovereignty during temporary British occupation in 1843.

My favorite statue is the Statue of Liberty. It represents an idea, liberty, which never really changes.

In a society in which nothing seems permanent and everything is susceptible to manipulation, the antiquated statue may be the perfect antithesis. At their worst, statues remind us of our vulnerability to oppression. But at their best, they inspire us to overcome adversity and persevere into the uncharted future.

This ran in our “explore” section, click to read the other stories: An Upstream Battle and Bibliophilia for Botanicals.