From homegrown artists to ʻāina stewardship, the leeward side is a showcase of the Garden Isle’s authentic rural identity even in the face of growing tourism and outside influences.

Images by Jesse Recor

Rounding the southern bend westbound on Kaua‘i’s only highway, the rain-slicked hills of Kalaheo fall away to reveal an expanse of golden-brown fields and deep green valleys that stretch from ‘Ele‘ele, the unofficial gateway to the island’s leeward side, to the roadway’s terminus. From the illustrious rust-red dirt that paints the region from seaside to ridgeline to the sky blue water that pools along the shores of Polihale, this is the raw, unfolding landscape of Kaua‘i’s west side.

On Kaua‘i, the west side’s past runs like a deep breath through the minds and hearts of its people today. The steadfast history of this place is inseparable from its community, from the Native Hawaiians who prospered here long before European arrival to the sugarcane plantations that reshaped its landscape. Hanapēpē, for example, and its legacy of resistance against plantation owners illustrates how this locality’s history is fundamentally interwoven with its present-day spirit and identity.

Home to many Native Hawaiians and locals whose families arrived to work on the plantations in the 19th century, the west side has held fiercely onto its heart and soul amidst the creep of tourism and outsider interests. Since the island’s economy shifted away from industrial agriculture, all of its inhabitants have felt the impact of encroaching large-scale development. Quaint towns like Hanapēpē and Waimea remain ardently defended by local residents who firmly wish to preserve Kaua‘i’s authentic spirit through a vision of mutual respect, reciprocity, and aloha ‘āina

For those spending time here, whether on their way to Waimea Canyon or visiting their favorite local shops, there are opportunities to listen and learn about the hands, feet, and faces of those who maintain the environmental and cultural richness of the west side — opportunities to slow down, appreciate, and give back to the place that so many know and already love.

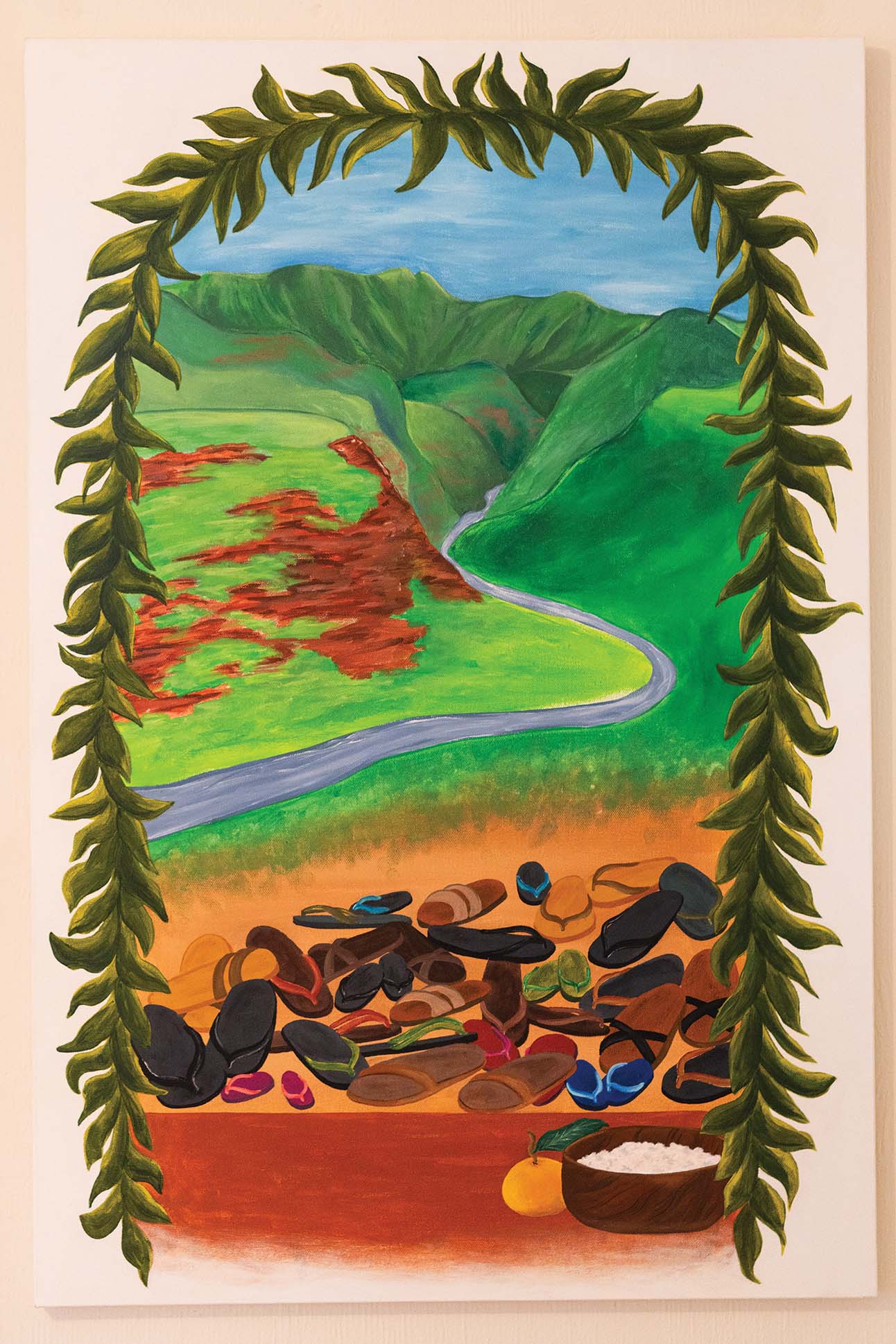

A smiling Holly Ka‘iakapu greets me in a sun-soaked courtyard in Hanapēpē town, where she intermittently calls out to friends and neighbors as they wander in: “Tita, good to see you!” Ka‘iakapu, an interdisciplinary Kanaka Maoli artist born and raised on Kaua‘i, is working to generate a new vibrant public art space and to keep imagery of Hawaiian moʻolelo alive. “I just love where I’m from, that’s the root of my art,” Ka‘iakapu says of her artwork, which is informed by her upbringing on Kaua‘i’s west side. “Hanapēpē is home. My grandparents, both of them are from Hanapēpē. I feel like there’s nowhere else that I should be.”

Raised in her family’s ecru-colored, two-story home that rests on the banks of the winding Hanapēpē River, Ka‘iakapu grew up with her feet on the same earth as her Hawaiian ancestors. An innate understanding and reverence for the traditions of the generations that came before her inspire her colorful murals and paintings, depicting native values and storied legends. When asked about her creative process, she reveals a deeply spiritual approach, saying, “I sit and kilo (to watch or observe), letting these Hawaiian concepts speak to me.” In that sense, Ka‘iakapu likens her role as an artist to that of a messenger, using her work to honor and preserve practices, while educating others through her creations about “knowing what’s pono and what’s not,” specifically when it comes to representing Hawaiian culture in the modern world, she says. Ka‘iakapu acknowledges that her work also presents her opportunities to learn about her own culture. “It’s a way for me to learn about the different wahi pana,” or sacred spaces, she says. “I’m diving deeper into stories, which allows me to learn and then create the space for others to learn more.”

Ka‘iakapu’s artistic path took her from Kaua‘i to California, where she studied visual and public art at California State University, Monterey Bay. After returning home, she committed to her vision of creating meaningful public art tied to Hawaiian culture that would make her community proud. Her first mural project, on a two-story apartment building in Līhu‘e, debuted in 2020 during NirMānā Fest, a week-long mural festival revitalizing buildings around the island’s capital city, opening doors for more public art commissions.

One of the pieces she’s most proud of is a mural at Waimakaohi‘iaka, also known as Salt Pond Beach Park. The adjacent salt ponds, of which the beach draws its popular nickname, are deeply important to local ‘ohana, who have been harvesting salt here for centuries. Ka‘iakapu is dedicated to shedding light on this cultural practice still alive today. “[This mural] means so much to me and it’s a huge educational opportunity,” she says. “This is the only place in the Pacific archipelago where man farms earth for salt in this manner.” The mural invites visitors to transform from passive observers to active participants with interactive QR codes that offer access to the mo‘olelo and traditions represented in the work.

Ka‘iakapu’s murals can be found around the island, including downtown Līhuʻe, local bus stops, and the National Tropical Botanical Garden. She also participates in Hanapēpē Town’s Friday Art Nights, a monthly community gathering of local artisans, typically held on every first Friday. Ka‘iakapu, like so many of those around her, imagines a world where those who come to the west side do so with openness and respect. “I want curious visitors and people who ask how they can give back,” she says. “Not just be extractive. Be curious enough to ask how they can show up for Kaua‘i.”

‘Āina stewardship

Kumano I Ke Ala

Tucked beneath the sun-bleached hillsides of Waimea stretch acres of land with the capacity to nurture lo‘i kalo, the very staple of life in Hawai‘i. Waimea, once the home to thriving Native Hawaiian food systems, has seen many environmental changes over time, often a result of over-development and mismanagement. For over a hundred years, sugar plantations dominated Waimea, a bygone industry that now has fallen into complete decay, leaving the ghostly skeletons of once-thriving mills littered about the island.

Thankfully, this Kaua‘i farm in Makaweli Valley tells a different story.

Community workdays go beyond a simple volunteer opportunity; they are a form of collective engagement. “I know many people have their church days on Sunday,” Kaina Makua says. “For us, this is our time together, our church, at this farm.”

Today, the nonprofit Kumano I Ke Ala is dedicated to restoring the west side through its ‘ōpio, or youth, development programs that aim to encourage the next generation of cultural practitioners. Sited on a 50-acres of land in Waimea, KIKA offers workshops centered around an ‘āina-based curriculum. The mindfully structured and supportive environment offers its community youth stability that they may not find elsewhere. Kaina Makua, co-founder and executive director of KIKA, outlines the program’s core values: laulima (teamwork), kuleana (responsibility), and aloha ʻāina (love of the land), with ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi lessons woven into the curriculum. “Different words and ideas,” he says, “but they all come from the same lens.” Born and raised on Kaua‘i, Makua founded KIKA in 2007, leveraging his polymathic skills in fishing, hunting, and farming to lead the nonprofit’s conservation efforts while representing Hawai‘i’s values locally and abroad (he’s soon to appear as Kamehameha in Jason Momoa’s Chief of War, an upcoming Apple TV series about the unification of Hawai‘i).

These youth-centered activities include learning about Hawai‘i’s native plants, harvesting crops, pounding and cooking kalo, and teaching them the farm’s full life cycle. A strong emphasis is placed on instilling work ethic and a sense of responsibility in Kaua‘i’s youth given that a thriving farm relies on a collective effort. “The only way the canoe is going to keep going in the direction and speed it needs to go in,” Makua says, “we all have to buy into that together and every person needs to pull their weight.” His answer is a

compelling allegory for the Native Hawaiian commitment to collectivism, so often challenged by the individualistic thinking that threatens the social fabric and ecology of Kaua‘i today.

Visitors and locals eager to get their hands dirty are invited to participate in community workdays, typically held on the second Sunday of each month. Community workdays can draw anywhere from 30 to 80 volunteers, with workdays addressing whatever is needed at the time of the farm’s lifecycle, from cultivating wetland taro fields to uhauhumu pōhaku, or Hawaiian dry-stack stone masonry. These community workdays go beyond a simple volunteer opportunity — they are a form of collective community engagement. “I know many people have their church days on Sunday,” Makua says. “For us, this is our time together, our church, at this farm.” For those who are unable to attend in person, Makua encourages supporting the organization through donations. “You know, reciprocity is key,” he says. Makua advises malihini to the island to give back in whatever ways they can: support ‘āina-based initiatives by volunteering, donate to local causes, or find similar farms to support across Hawai‘i.

retail

Fonda’s Daughter

Nestled next to Hanapēpē’s Hawaiian Congregational Church, Fonda’s Daughter co-founders Natalie Fonda and her husband Kekoa Seward have opened a Hawaiiana vintage store that feels like stepping back in time. The extensive curation put into this collection of items — from mu’umu’u to aloha shirts to old music records — is so clearly a labor of love, one can’t help but be drawn in by what Fonda describes as an “organized treasure hunt.” At Fonda’s Daughter, Fonda and Seward specialize in showcasing and preserving vintage pieces, often rescuing items that might otherwise be thrown away, ensuring that a piece of history lives on.

Growing up on O‘ahu, in the windward community of Ka‘a‘awa in the 1990s, Fonda was raised with the love of all things vintage. Her father, Fulvio Fonda, moved their family to Hawai‘i from the Bay Area in her early childhood. Being raised by a vintage dealer with a passion for aloha shirts meant that as a little girl she would tag along every weekend to the Aloha Stadium swap meet, a formative experience that shaped her deep connection to vintage Hawaiiana culture and inspired the shop’s name, Fonda’s Daughter. As an adult, Fonda continues to travel to O‘ahu every Sunday, joining her father to search for exciting finds in a ritual that demonstrates the intergenerational labor of love that underlies the heart of the shop’s endeavor.

Scattered around the little shop, one will find handwritten signs that designate each rack with the item’s name in ‘ōlelo Hawai‘i, a handmade touch from Seward’s mother, who can often be found lei-making out front on Hanapēpē Friday Art Nights, to imbue the space with a sense of Hawaiian identity. “Any opportunity we have to teach visitors the history and culture, it’s important,” Fonda says. “I think we have a responsibility to do that. I wasn’t born here, but I was raised here from the time I was 5-years-old and my husband’s family goes back generations. My daughter is part-Hawaiian. I believe we have a duty to teach her the history as well.”

We’re trying to keep that original charm, not gentrify it.

Kekoa Seward

The Hawaiiana vintage store feels like stepping back in time, extensively curated with muʻumuʻu, aloha shirts, and unique collectibles like old-school pogs and pins.

For visitors, the shop provides an opportunity to move beyond surface-level experiences of Hawai‘i. Fonda and Seward encourage tourists to immerse themselves, learn about local perspectives, and connect with the island’s true essence. For locals, it’s a nostalgic dive into our recent past, delighting local customers young and old who find beautifully maintained vintage mu‘umu‘u or a graphic T-shirt that reminds them of the one their uncle used to wear. Fonda is committed to keeping prices reasonable so locals can continue to shop hvere. “I know the history and the story that comes with a mu’u mu’u or an aloha shirt,’ she says. “Everything has a memory behind it and I think that’s most important. Sometimes I have people coming in and saying, ‘Oh I wish I had saved a bunch of my grandma’s things,’ and seeing their faces light up when they pull an item and go, ‘Oh my gosh, I see my grandma or my grandpa in this…’ They bring so many good memories with them.”

NATure

Kaua‘i Forest Bird Recovery Project

In the heart of Kōkeʻe’s forests lives a small, gray-feathered bird named Pakele, meaning “to escape” in ‘ōlelo Hawaiʻi. Pakele is an ‘akikiki, one of Kauaʻi’s rarest birds. With only two of her kind remaining in the wild, Pakele’s very existence is a testament to her name, a daily flight from the brink of extinction. Dr. Julia Diegmann, a scientist with the Kaua‘i Forest Bird Recovery Project, speaks of Pakele with the fondness and knowledge of a close friend, describing her as “remarkable.”

“She truly has been escaping,” Diegmann says, believing Pakele holds the record for the female ‘akikiki with the most nests ever found. “She should be extinct and she just keeps going.” This resilience, however, underscores the precariousness of her species’ situation.

Kaua‘i’s native birds face a multitude of urgent threats with avian malaria, spread by invasive mosquitoes, posing the greatest danger. Rapid ʻŌhiʻa Death, a fungal disease targeting the ʻōhiʻa tree, a foundational species in Hawaiʻi’s forests, is another significant challenge. “All remaining forest birds depend on healthy ʻōhiʻa forests,” Diegman explains. “So, if we lose our ʻōhiʻa trees, like other islands are losing theirs, we will lose our habitat for our native forest birds.” These threats make the work of Kaua‘i Forest Bird Recovery Project, a nonprofit aiming to promote knowledge, appreciation, and conservation of the island’s native forest birds, all the more critical — and Pakele’s survival all the more extraordinary.

Based in Hanapēpē, Kaua‘i Forest Bird Recovery Project’s crucial efforts focus on one threatened species (‘i‘iwi) and three federally endangered species (‘akikiki, puaiohi, and ‘akeke‘e) within the forests of Kōkeʻe. With six bird species found nowhere else on Earth, Kauaʻi’s bird population is an irreplaceable part of the island’s natural and cultural heritage. These animals play a vital role in its ecosystem, pollinating native plants, controlling insect populations, and dispersing seeds, all essential to maintaining healthy Kaua‘i forests. Conservation efforts are driven by the dedication of nonprofit’s individuals, but also depend on the awareness and actions of everyone who lives on or visits Kaua‘i. Taking precautions to avoid spreading Rapid ʻŌhiʻa Death, such as cleaning shoes and clothing, is crucial. “Pack out what you pack in,” Diegmann advises, “and leave the forest better than you found it.” She also recommends exploring the project’s website for resources, including guides on responsible birdwatching. “What I want to stress is that when you think about how Native Hawaiians view visiting these birds in sacred areas like Kōke’e,” Diegmann says, “be aware that you are really privileged to go there.” She encourages visitors to the forests to approach these areas with gratitude and respect.

For those eager to get involved, visitors can participate in occasional volunteer trips, support the organization through donations, or purchase merchandise that directly funds conservation projects. These items, including shirts and mugs, are available at the Alakoko Shop in Līhuʻe and the project’s headquarters in Hanapēpē. Local volunteers are always invited to assist with community outreach and mosquito control. “Support conservation by talking to your friends and talking to your elected officials,” Diegmann says, stressing the importance of grassroots and direct advocacy. “Tell them you don’t want to see these birds go extinct. They need to hear from people who care about these species.”