The uncharted tale of history’s only Native Hawaiian whaling captain, culled from an archival abyss of explorer logs, scholarly mentions, and aging newsprint.

Nā pe‘a i ka makani

THE SAILS IN THE WIND

With the wind freshening toward morning’s end, George Gilley’s little whaleboat held its lead. The sharp-set prows of the larger ships Sarah, Kapiolani, and Mokuola nipped at his wake as he rounded the flag-boat at Waikīkī, sprinted westward to a buoy near the Pearl River mouth, and then beat back through the early afternoon to the finish line at Honolulu Harbor. There at the wharf, where Aloha Tower would stand half a century later, a crowd of 5,000 revelers thronged the esplanade, cheering as Gilley sailed first through the flag-festooned channel.

The race launched the sporting festivities for King Kalākaua’s 44th birthday, November 16, 1880. Reporting on the celebration, the Pacific Commercial Advertiser described a collective “spontaneity of spirit, an enthusiasm, and at the same time, a peacefulness of demeanor; proving a widespread loyalty … prevails among all races of our population.” But it is hard to say if such feelings were stirred in George Gilley. The whaleboat that he had rigged with a sail likely came from the schooner Julia A. Long, which had just completed the final whaling expedition undertaken by any Hawaiian-registered ship. As its captain—the only known Native Hawaiian whaling captain in history—Gilley was out of work. Was he driven to win the race for king and country? Or was it for the $50 prize, a hefty payday for a whaleman without prospects?

Gilley’s life story, which has never been told in full, is rife with such questions. But one thing we might reasonably infer, after weaving together the scattered mentions of his name—spelled Gilley, Gilly, Gillie, Gelley, or Kele—in newspapers, letters, and explorer accounts, is that a festive day spent riding island breezes around buoys was much easier than his average foray. In the years well before and after that day, Gilley navigated Arctic storms and treacherous fields of coral, ice, and thrashing leviathans that shivered the timbers of all who braved the North Pacific in the great blubber rush of the 19th century. Propelled by a jetstream of sheer talent, Gilley was an exemplar of the Native Hawaiian initiative, skill, and fearlessness that rendered a small island kingdom a player in the global economy.

When 18th-century Kānaka Maoli, or “real people” in Hawaiian, applied the word for their islands, moku, to the foreign ships arriving at their birth sands, they implicitly continued a deep-routed tradition of Polynesian migration and island colonization. This semantic act soon translated into real Kānaka seamen making gains throughout the floating archipelago of ships built by nations seeking economic footholds in their islands. Navigating his way to the top of this movement, and furthest beyond the West’s maritime color lines, George Gilley led his predominantly Pacific Islander crews into a novel form of sovereignty in the post-contact era.

Yet when a moth-eaten memory of Gilley is occasionally brought forth in whaling histories, it rarely highlights his dynamism. Most often, writers cite the so-called “Gilley Affair” that transpired just three years before Kalākaua’s birthday race, when a close shave with the westernmost tip of North America resulted in Gilley’s crew swabbing the decks clean of blood that belonged not to whales but to Iñupiat—“real people” in the Iñupiaq language. But taking a brief, telescopic view of that gruesome picture denies Gilley the full scope of his unrivaled life, which began decades earlier, several seas away.

E komo ʻĀkia

GONE TO ASIA

In 1830, a British ship captained by Samuel Dowsett carried 13 pioneering Kānaka Maoli from Hawai‘i nearly 4,000 miles westward to the uninhabited Bonin Islands, 600 miles south of Tokyo. Accompanying them were five white men—their indenturers and in a few cases husbands—who intended to colonize the island group for England. They settled on Peel Island, now known as Chichijima. By 1835, their grass-hut settlement attracted at least six more enterprising wāhine and several other disaffected Westerners, including Englishman William Gilley. One of the colony’s 16 wāhine bore children who took his name—among them William Jr., Michael, Lizzie, and around 1840, George.

Growing up in this distant microcosm of colonial Hawai‘i, young George thrived on Hawaiian staples, from fresh fish and wild pig to sweet potatoes and sugarcane. His life was defined by the sea. He learned to sail on outrigger canoes made for interisland travel and, at first, likely hunted turtles. In 1837, visiting British captain Michael Quin observed the settlers’ efficient use of island resources, including its many sharks, which he saw “the dogs frequently chase in shoal water, capture and drag high and dry on the sandy beach.” Other supplies came by way of roving whalers that occasionally appeared on the eastern horizon. As a teenager, George Gilley jumped at the first opportunity to leave on one, arriving in Hawai‘i via a whaling ship and sticking around. An 1855 letter, sent to the Bonin Islands from a family friend in Honolulu, mentioned that “George has been here 2 or 3 times but I could not persuade him to go home and see his mother. He seems to like this place so much.”

Through the mid-19th century, Honolulu and Lahaina were the de facto dispatch hubs for ships en route to the cold, whale-rich waters off Japan. Most of these ships hailed from Nantucket and New Bedford, Massachusetts, and brought to the islands everything from bricks to syphilis to Christian missionaries. They also presented opportunities for Kānaka Maoli. In 1840, Richard Henry Dana Jr.’s bestselling sailing memoir Two Years Before the Mast broadcast the enviable talents of “Sandwich-Islanders” who made their way from whaling into the fur trade on California’s coast. “Ready and active in the rigging,” wrote Dana, these “complete water-dogs” schooled their New England counterparts in the art of landing small boats through the Santa Barbara surf.

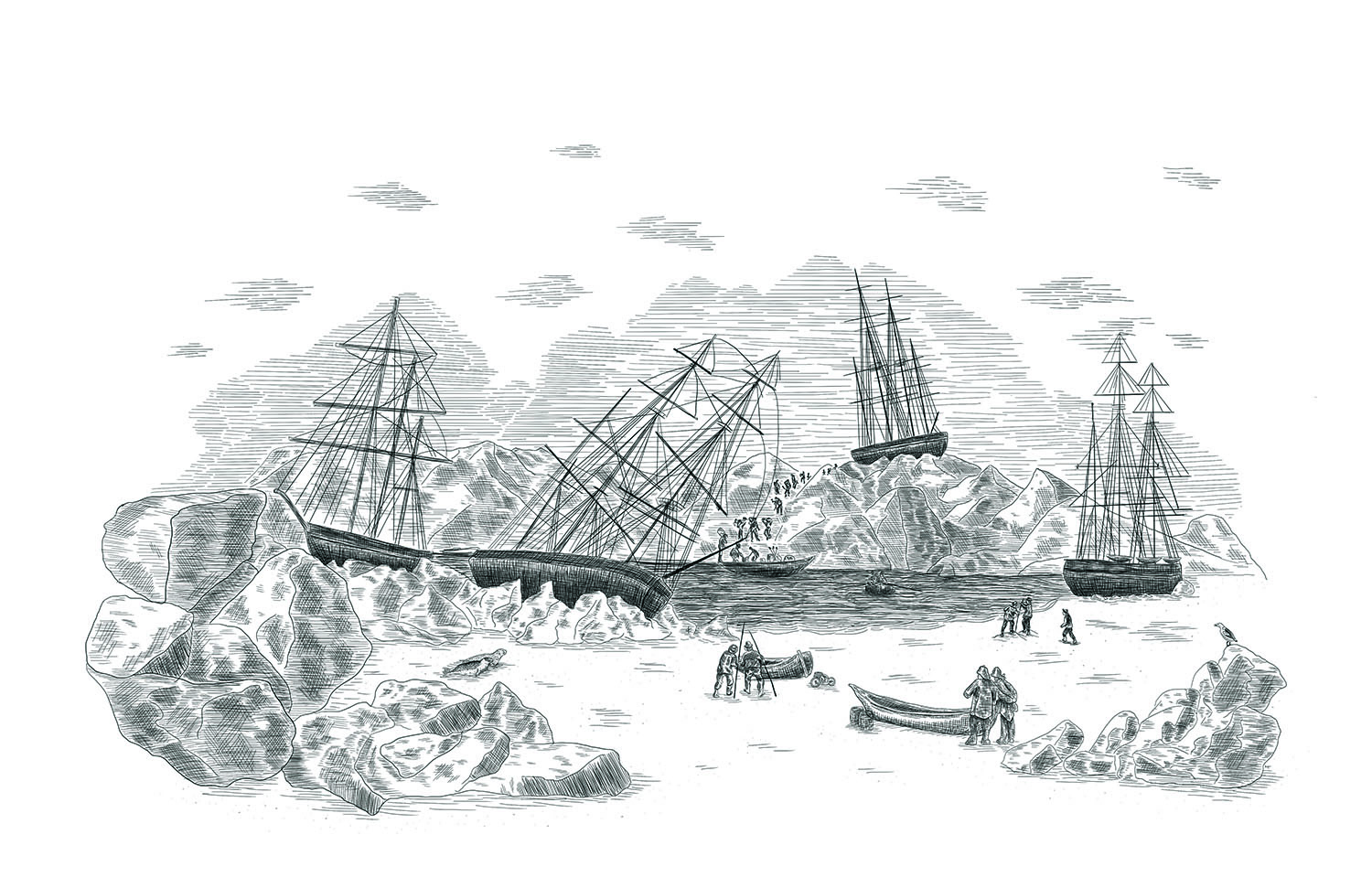

circa 1830s

Small-craft skills were vital to the whaling industry, which partly explains for the quick rise of Pacific Islanders to the coveted, harpoon-wielding position of boatsteerer—a trend caricatured by Herman Melville’s Queequeg in Moby-Dick. However, Hawaiians ascended well beyond token status on board, and often manned the full span of positions available on a single ship. Even as outsourced laborers, they gleaned competitive seasonal wages ranging from $5 to $200. Between the roughly 5,000 Kānaka Maoli who signed onto whaleships between 1842 and 1867 alone, the profits Hawai‘i skimmed off the American market stacked up. The real booty, however, lay in selling oil to the burgeoning empire, which needed it to light and lubricate its industrial revolutions. As early as 1832, Hawai‘i’s financiers began flipping used ships and assembling a local whaling fleet. Fitted with high-flying Hawaiian flags proclaiming the monarchy’s might, the budding flotilla was loaded with homegrown talent and launched into the wind.

Ke kōā o Pēlina

THE BERING STRAIT

According to one newspaper, young George Gilley was on the scent of Arctic whales by 1862, aboard the Hawaiian-registered Kohola under Captain Brummerhop. This could have included his first “wintering over” in the Bering Strait, at eastern Siberia’s St. Lawrence Bay. If he was there, locked in sea ice awaiting the spring hunt, he surely marveled when Siberian Yupik traders emerged from the white landscape to deliver vital deer meat to the crew. The favor, however, backfired on one such visitor, Capatchou, who became trapped on the ship during a gale. Desperate to see his family, Capatchou futilely begged Brummerhop for help ashore, jumped overboard to attempt the frigid swim, and disappeared.

Later, Gilley would have heard gunshots echo across the ice as the captain tried to defend himself from the vengeful arrows and spears of Capatchou’s relatives at their village. The crew were only returned Brummerhop’s clothing, but never his body. When the Kohola resumed its methodical decimation of the Yupiks’ source of whale meat and muktuk (a skin and blubber dish) in the spring, five of Gilley’s fellow Kānaka died of scurvy, followed by three more from other diseases. Sailed by first mate Bernard Cogan, the Kohola returned to Honolulu in the fall of 1863 with 600 barrels of bowhead whale oil and 10,000 pounds of baleen, which equates to about six kills. Between 1847 and 1867, whalers would remove more than 18,000 bowheads from the Arctic—more than the entire population in the region today.

In 1863, Gilley’s father (or possibly brother), William, was reportedly murdered, which might explain why an 1870 letter written by Lizzie suggests that Gilley had returned to the Bonin Islands. But by February 14, 1872, the Hawaiian Gazette listed a sailor named “Gillie” on the Honolulu yacht Henrietta who is “counted among the most expert whalemen that belong here.” Although the Henrietta was slated for a two-month shark hunt, the Advertiser reported on February 24 that “the crew of the Henrietta have struck three whales since leaving here; one sunk and was lost; one they secured and tried out at Ukumehame, to the westward of Lahaina, and they were fast to another when last seen, on Monday, in the channel between Molokai and Lanai.” But was this our Gilley? The Advertiser confusingly identified this whaler as “R. Gillie,” a name found nowhere else in Hawai‘i’s whale-related press. By contrast, misinformation and misspellings abound in these papers—Brummerhop’s name, for example, was rarely spelled the same way twice.

In any case, Gilley would have needed exactly the kinds of experiences gained on the Kohola and Henrietta to explain how by 1875 the approximately 35-year-old was listed as captain of the brig Onward, becoming the only known Kanaka Maoli to achieve that title on a whaleship. Owned by Honolulu businessman James Dowsett, son of the Captain Dowsett who ferried the first settlers to the Bonin Islands, the Onward was a force in the kingdom’s whaling fleet. In Gilley’s first recorded season as a captain, he proved his worth. Following a successful spring hunt, the Advertiser reported in November that the brig Onward sailed into port with her casks brimming with oil, thanks to Gilley’s winning gamble on a once-popular whaling ground near Alaska’s Kodiak Island.

Ke liolio nei ke kaula likini

THE RIGGING LINES TIGHTEN

In December 1876, Dowsett hired Gilley again, to captain the William H. Allen for a short hunt along the equator—a late-season trip likely intended to recoup some of the year’s Arctic losses. That summer, at least 12 ships, including the Honolulu barks Arctic and Desmond, had been lost to rogue ice floes off Nuvuk, or Point Barrow, on the north coast of Alaska. It seems that delays in fitting out the William H. Allen spared Gilley the hardship faced by the 300 seamen stranded on the ice, though there is a chance he had been present for the even greater disaster of 1871, five years prior, which had claimed 33 ships, including the Kohola and three other Hawaiian-registered vessels. When not listed as a captain, a whaler’s story is difficult to track—unless they wrote it down.

Such was the case for Kanaka seaman Charles Edward Kealoha, whom Gilley saw hurtling toward him over the ice dunes near Tangent Point, Alaska in early August 1877. Gilley was again at the helm of the William H. Allen, having embarked from Honolulu on April 21. Kealoha, on the other hand, had been on Alaska’s north slope for almost a year. He and a Mā’ohi whaler named Kenela, both of the Desmond, were the last survivors of at least 50 men who had stayed behind in Alaska when others took their chances on a few crowded ships that escaped the ice. These two Pacific Islanders persevered by the grace of Iñupiat who brought them to their warm caves and fed them fatty fish and orca meat.

1862

Kealoha’s firsthand account of this harrowing winter was published in the Hawaiian newspaper Ka Lahui Hawaii, and was recently brought to light by Susan Lebo in the Journal of Hawaiian History. Lebo highlights the warm reception Kealoha received from Gilley, whom he referred to as “he keiki Hawaii Ponoi,” or one of Hawai‘i’s own children, and whose moku provided a feeling of being “i ka aina hanau,” in the birth land. Lebo’s article, which features translations by Bryan Kuwada and Puakea Nogelmeier, also includes an account by J. Polapola, one of Gilley’s Kanaka crew. Lebo imagines Kealoha likely spent many hours sharing stories with Polapola in the crew’s quarters, though we can only guess what horrors swept through Kealoha’s mind as Polapola described the massacre that occurred on the decks above them two months before.

E niniu i ka makani

SPINNING IN THE WIND

In his initial report to the Advertiser recapping the 1877 whaling and walrusing season, Captain Gilley, who was rarely quoted in the press, mentioned briefly that on “June 5th, while becalmed between Cape East and Cape Prince of Wales, three canoes approached the vessel, for the purpose of obtaining liquor, but were refused, on account of their being drunk, in consequence thereof a row ensued on board, and we were compelled to drive them off as soon as possible, resulting in killing of one of the crew (Hawaiian) and wounding two.” In the same paper, Captain Owen of the Three Brothers offered “a heartfelt thanks to Capt Gilley” for rescuing him after his ship was frozen in pack-ice near Nuvuk.

Only one of these leads interested the sensationalist journalists of the day. A correspondent for the San Francisco Chronicle quickly penned “A Whaleship’s Escape” about Gilley’s tragic encounter with the Iñupiat, in which he claimed to dispel the “wildest rumors” by presenting facts gained through an interview with the captain. Yet the writer went on to describe how “the vessel was overpowered” by “seventy five warriors,” led by a 6-foot-6-inch tall chief who seized Gilley by the throat and signaled his determination “to take charge of the vessel, run her ashore, and murder the officers and crew.” With dramatic flair, the writer flipped this fate, one dead “redskin” at a time. The Chronicle’s version was soon reprinted as far east as Chicago, feeding American readers images of a cowboys-and-Indians-style shootout at sea.

In time, Gilley’s account took on a racialized Rashomon effect. Where the Chronicle noted an Iñupiaq committed the first murder, journalist Herbert L. Aldrich, in his 1889 book Arctic Alaska and Siberia, quoted Gilley saying that one of his own men initially killed a chief by tapping him on the head with a wooden handspike. In 1890, the U.S. Bureau of Education’s first English-Eskimo and Eskimo-English Vocabularies included a rendition in which Gilley shot the chief immediately after “the natives drove the crew below, killing one man.” Here, Gilley’s crew, which included two Yupik men, was implicitly white. Later still, in his 1942 memoir Fifty Years Below Zero, Arctic resident Charles Brower recalled Gilley placing first blood on the hands of his hotheaded Irish first mate, Finnigan. A variation of this man had appeared in the Chronicle story too, when Gilley first saw that “a Sandwich Islander lay murdered on the deck,” and shouted, “It’s life or death with us, Murphy; are you ready for action?”

All accounts considered, around 15 Iñupiat were killed. Most concluded, in patently racist terms, that Gilley had taught the wily natives better than to interfere with the white man’s industry—concealing the ill-kept secret that whalers, including Gilley, were illegally trading liquor for Iñupiat furs. Brower went so far as to describe Gilley himself as a white man, and quoted him saying, “No, sir, they don’t like whites much around Cape Prince of Wales.” While we might wonder if Gilley, being hapa, occasionally engaged in racial passing, it seems more likely that writers like Brower simply preferred drawing within set color lines.

But one account spurs us to believe that for Gilley, the incident was not so black and white. Huddled in the William H. Allen’s forecastle in the fall of 1877, J. Polapola didn’t just write down another play-by-play; he wrote a confession. Unlike all the secondhand reporters, he was there, on the deck, and the aforementioned handspike was actually in his hands when the chief took Gilley by the throat.

Before he knew what he was doing, Polapola had hurled the heavy rod at the chief’s brother, striking him in the neck. “Ke kaikaina alii a haule make aku la iluna o ka oneki,” Polapola wrote—the chief’s younger brother dropped dead onto the deck. But rather than calling the first mate to action, as the Chronicle wished, Gilley shouted just one thing, in Polapola’s account: “Don’t kill him yet.”

It seems Gilley had tried to cut short the violence by sparing the chief. And when Kanaka seaman Honuailealea was stabbed in retribution, it doesn’t appear that all the “Kanakas went crazy … grabbed axes and spades and lit into those damned Eskimos” as Brower claimed. At least two Kānaka, named Paia and Kahele, and presumably both of the Yupik crewmembers, abstained from violence. But others in the fight, including Gilley, knew Hawai‘i’s whaling fleet was down to just four ships, and that theirs contained about $36,000 worth of cargo, according to Polapola.

Losing it was not an option. Only after laying out this rationale did Polapola state, without a rhetorical flourish or flinch, “The captain seized the chief by the neck, gave him a bullet in the face and threw him into the sea.”

1877

‘A‘ole i kau pono

UNFIXED

This is where nearly all accounts of Gilley’s life leave him: standing amidship in the full sun of an Alaskan summer night, smoking gun in hand. He serves as a slick, disposable anecdote, used historically to reinforce racism toward Iñupiat and later to distill the social friction at whaling’s periphery. But Gilley’s career, his own racial struggles, and his relations with the Arctic’s indigenous people extended far beyond 1877.

By contrast, the bloodsoaked William H. Allen did not last long. The ship resumed its hunt after the affair in June, but the sea served up few whales. On October 25, the ship belched forth only 200 barrels of walrus oil, 6,000 pounds of ivory, and 5,000 pounds of bone upon its return to Honolulu. Seven months later, Gilley again steered the William H. Allen north—fearlessly, or foolishly, north—back to Nuvuk, the northernmost point of North America. On August 2, Captain Dexter of the Loleta reported, “brig W H Allen was stove by ice, near Point Barrow; crew all saved; Captain Gilley on board the Onward.” Gilley remained on the familiar ship until it returned to Honolulu in November. With the subsequent loss of the Florence, Hawai‘i’s fleet, which had grown by two ships that year, was again down to four.

Ka‘a ‘ē ka huila

THE WHEEL TURNS ELSEWHERE

Unphased by Gilley’s loss of the ship, and the single liquified whale that had been in its belly, Honolulu’s investors placed him at the helm of the Giovanni Apiani in 1879. But the Arctic he encountered that year had changed. He reported to the Advertiser that he found no whales, just plenty of starving people, such that he “killed two schooner loads of walruses and carried them along the settlements and gave to the natives.” Contrary to popular belief, Gilley had no interest in exterminating his trading partners. He gave them his entire haul. On October 27, he returned to Honolulu with just 1,218 pounds of tobacco, 5.5 barrels of rum, and other trade goods. The Giovanni Apiani was sold the next year, and landed on the last Hawaiian ship to feed in the Arctic, the Julia A. Long. In many senses, it was a classic whaling season: He cruised the reliably stormy seas around St. Lawrence Island, south of the Bering Strait, caught half a dozen bowheads, and performed a routine rescue when Captain Dexter ran aground in the Loleta. He even had an encounter with ichthyologist Tarleton H. Bean, then curator of fishes for U.S. National Museum, and told him about a favorite walrus-hunting spot on Hall Island further south. In spite of these high notes, Hawai‘i’s local whaling industry folded when he returned to port on October 10, 1880.

Sometime around Kalākaua’s birthday race in 1880, Gilley registered a home address in Pauoa, O‘ahu, but he did not stay there long. He followed the whaling industry to San Francisco, where he became captain of the bark Eliza until at least 1884, touching at Honolulu occasionally. By 1886, the middle-aged whaler downgraded station but upgraded technology, becoming first mate on the steam-powered Grampus. No longer captain, Gilley lost regular listing in whaleship reports. In 1887, however, he had his encounter with Herbert L. Aldrich, who took his picture, standing on the decks of what could be the Grampus. In this only known photograph of Gilley, the man appears entirely self-possessed, suited up in a thick, greasy furs, smoking a pipe, bare hands tucked in at the waist, serious eyes half-squinting through the Arctic light. Behind him are two other men, possibly Iñupiat or Yupik, one of whom is crossing the deck with a blubber spade while the other looks on.

In December 1890, Gilley, then first mate of the steam-whaler Thrasher, was the subject of a leprosy scare. Although a health officer in San Francisco initially declared his symptoms to be “a severe case of eczema,” his shipmates apparently insisted he be taken to the “pest house” for further monitoring, claiming that “his wife, who was formerly a resident of this city, but who now lives at Yokohama, is also a leper.” These intriguing details about his wife are difficult to corroborate, but one has to wonder whether Gilley’s ethnicity and associations with Hawai‘i, and maybe Japan, played into the false assumption that he was “also a leper.” In November 1897, the San Francisco Call ran a feature on Gilley, then boatsteerer of the Thrasher, complete with an illustrated portrait of him in a three-piece suit. The headline was familiar: “Captain George Gilly: Forty Years an Arctic Whale-Hunter, Who Has Killed a Few Esquimaux.” Besides a rehashed telling of the “Gilley Affair,” the article claimed that Gilley “has gone to the Arctic Ocean every year for forty years past.” If true, that placed him in the Arctic even before Brummerhop’s mishap, most likely when he was a teenager.

1880

In 1898, Gilley blew onto yet another ship, the Andrew Hicks, becoming first mate to none other than Captain William Shorey, aka Black Ahab, the first and only black whaling captain in the Pacific. In April, the two sailed from San Francisco, stopping in Honolulu for provisions. The Pacific Commercial Advertiser hailed their arrival, calling Gilley “a half-caste of this Island.” When in Hawaiian waters, any chance or need for racial passing vanished. The same went for Shorey’s ship. The captain deliberately sought out Kānaka Maoli to improve his odds in the increasingly difficult industry. “Hawaiians are fearless on the water,” he told a reporter during the visit. “They will chase a whale when they know they are in the greatest danger and think it is the greatest fun. If a boat is capsized it makes no difference to them for they can swim like fishes. I do not know of any people who are better suited for our business. They are absolutely fearless.” Perhaps this is why Gilley kept at it so long, kept risking the ice, the disease, the skirmishes, and thrashing tails of leviathans—it was the greatest fun. Or maybe he relished having sovereign power over his moku, or at least his own whaleboat. For even after finding such comradery with Shorey, and returning to the suddenly American city of Honolulu, he again sought the Arctic, one last time.

Aia i ʻĀlika ka ihu o ka moku

THERE IN THE ARCTIC, THE PROW OF THE SHIP

In 1899, gold was discovered at the coastal settlement of Nome, Alaska, drawing thousands of prospectors and, apparently, George Gilley, who arrived via the bark Alaska in the spring of 1900. He floated into the captainship of the schooner Edith, and began trading from Nome around the Bering Sea. In August, he sailed over to the Siberian coast, and anchored near the shore. Trading with locals went peaceably until one night, when Gilley’s first mate caught a mysterious, fatal bullet fired from the beach, forcing them to sail for Alaska at daybreak.

As the ship approached Sledge Island, about 20 miles offshore, Gilley took a seat on the ship’s rail and looked across the blue at the coast of stone gray and green. Then the wind shifted, and for once in his life, he did not rise to meet its force. The boom swung around and knocked George Gilley into the frigid sea. His men raced astern as the ship grazed onward, only to watch him drown. The crew worked like whalers, and not without difficulty, to hoist Gilley’s lifeless body out of the water, back into the crisp morning air. They took him on to Nome.

A few days later, a small newspaper in Oregon recorded the loss of a 60-year-old “native of the Island of Borneo,” “whose good or bad fortune it was to have killed five Northern Indians some years ago.” Later in the same article, this number is raised to 10. A few other West Coast papers ran similar accounts. His death was not evidently reported in Hawai‘i.

Ha‘ina ‘ia mai ana ka puana

SING THE SUMMARY REFRAIN

While Gilley’s iwi rest somewhere unknown, his name lives on in the Bonin Islands, known as the Ogasawara Islands since Japan claimed them in 1875. Due to this political and cultural shift, modern Gilleys are nearly as difficult to track as their historic relative. “Gilley” has been transliterated to “Gērē.” Family members have decided to choose entirely new names, a phenomenon studied by linguist Daniel Long, who stated that some of “the Gilleys, proud of the ‘South Sea Islander’ part of their roots, chose the name Minami,” meaning “south.” One such person, born in 1961, is named George. According to a 2018 article in the Asahi Shimbun newspaper, George (Gilley) Minami works on whaling and fishing ships, “continuing the family tradition.”