With Hawaiʻi Non-Linear, Sean Connelly and Dominic Leong work to unearth alternative futures for Hawaiʻi’s built environment.

For a decade, the O‘ahu-born artist and designer Sean Connelly has employed the tools of architecture to make art that challenges Western, colonial understandings of land. His 2013 installation, “A Small Area of Land (Kaka‘ako Earth Room),” a towering, monolithic slab of compacted soil and sand, was a critique of how land in Hawaiʻi has been commodified since the Kuleana Act of 1850.

Since then, Connelly’s work has become increasingly phantasmagoric, blurring the line between architecture, cartography, visual art, and film. In “O‘ahu, A Giant Military Base,” part of a larger, in-progress work, Israel Kamakawiwo‘ole’s “Somewhere Over the Rainbow” plays as a satellite image of Oʻahu morphs into a grotesque, almost cartoon-like collage of giant artillery shells, exploding ordinances, radar systems, and floating military logos—the island’s volcanic topography dwarfed by these oft-concealed infrastructures of war.

Now, Connelly has teamed up with New York-based architect Dominic Leong, an assistant professor of architecture at both Columbia University and MIT, to found Hawaiʻi Non-Linear, a trans-oceanic, queer- and indigenous-led architectural collaborative whose mission is to “create art and architecture for ‘āina.” (With his brother, Chris, Leong also runs the celebrated New York practice Leong Leong, perhaps best known for the Los Angeles LGBT Center’s Anita May Rosenstein Campus, a collection of clean, white volumes so light and airy that they feel weightless.)

With a goal of bridging the worlds of art, architecture, and activism, Hawaiʻi Non-Linear was founded as a nonprofit collaborative to help advance environmental justice and Native Hawaiian knowledge. As a practice, it straddles multiple disciplines and geographies, operating both within the rarefied world of East Coast architectural education and on the ground in Hawai‘i. Connecting its various modes are two braided beliefs: one, that architecture is political; and two, that Hawaiʻi has more to offer the field of architecture than scholars historically have assumed.

The collaboration was born out of the social unrest of 2020. For Leong, who grew up in Northern California, regular visits to extended family on O‘ahu were formative in engendering a deep and sustained relationship to Hawai‘i.

“At the time, these experiences and connections weren’t articulated as part of a ‘cultural resurgence,’ they were just a way of life that was a mixture of my Chinese and Hawaiian roots through my father—embodied stories of surviving and thriving in the wake of colonialism, plantation life, and U.S. statehood,” Leong says.

Amid the institutional reckoning that followed the murder of George Floyd in 2020, Leong says he felt that he had a “specific responsibility within the architectural discipline, as [a part of the] Kānaka Maoli diaspora, to help pluralize the canon and articulate a more enriched understanding of architecture that is not limited by a Eurocentric legacy.”

Leong became particularly interested in the history of urbanization in Hawaiʻi. It wasn’t long before his research led him to Connelly. “I was really struck by the intersections he was working at, in terms of activism, urbanism, all these things,” Leong says. Meanwhile, Connelly had become increasingly disillusioned with Hawaiʻi’s architecture community, which he saw as unwilling to grapple with the history of U.S. imperialism in Hawai‘i. “When Dominic reached out it was like a beam of light,” Connelly says.

Through its work in and outside of the architecture profession, Hawaiʻi Non-Linear is attempting to make visible—and real—the latent futures that exist all across Hawai‘i.

Timothy A. Schuler

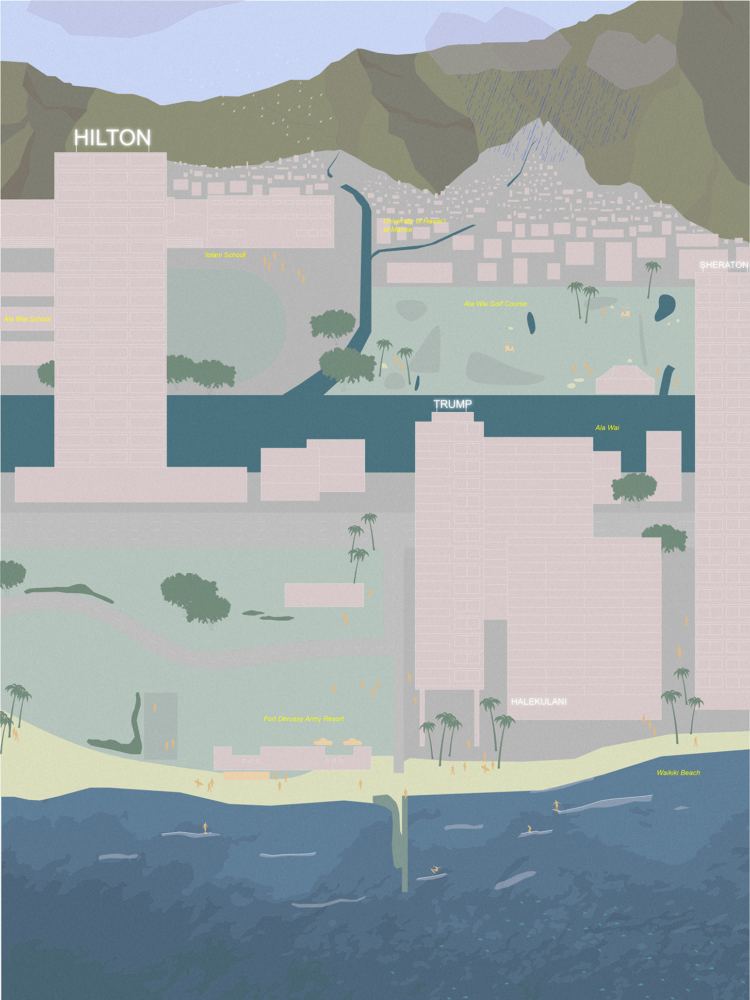

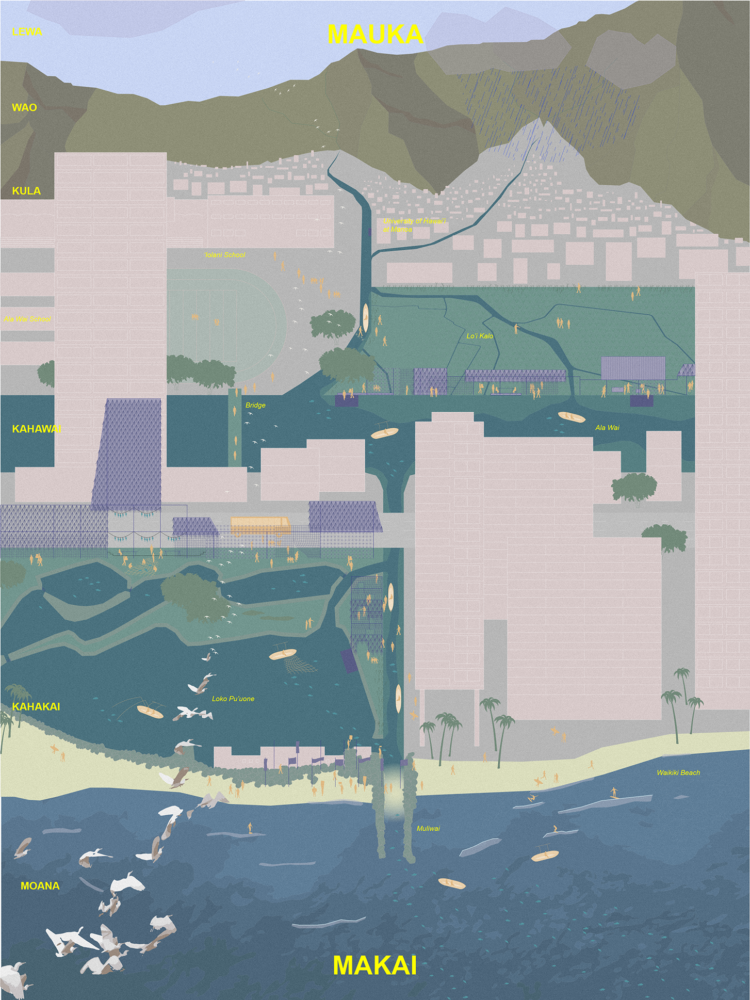

In Fall 2020, Leong and his brother invited Connelly to co-teach a design studio at Columbia based around Connelly’s Ala Wai Centennial Memorial Project, a proposal to incrementally reclaim Waikīkī—and eventually the entire ahupua‘a—for more regenerative and just uses. “I felt that it was both personally and professionally important to support Sean’s work in the context of architectural education,” Leong says, and to expose students “to a deeper analysis of the connections between the history of colonialism and U.S. urbanism in Hawaiʻi.”

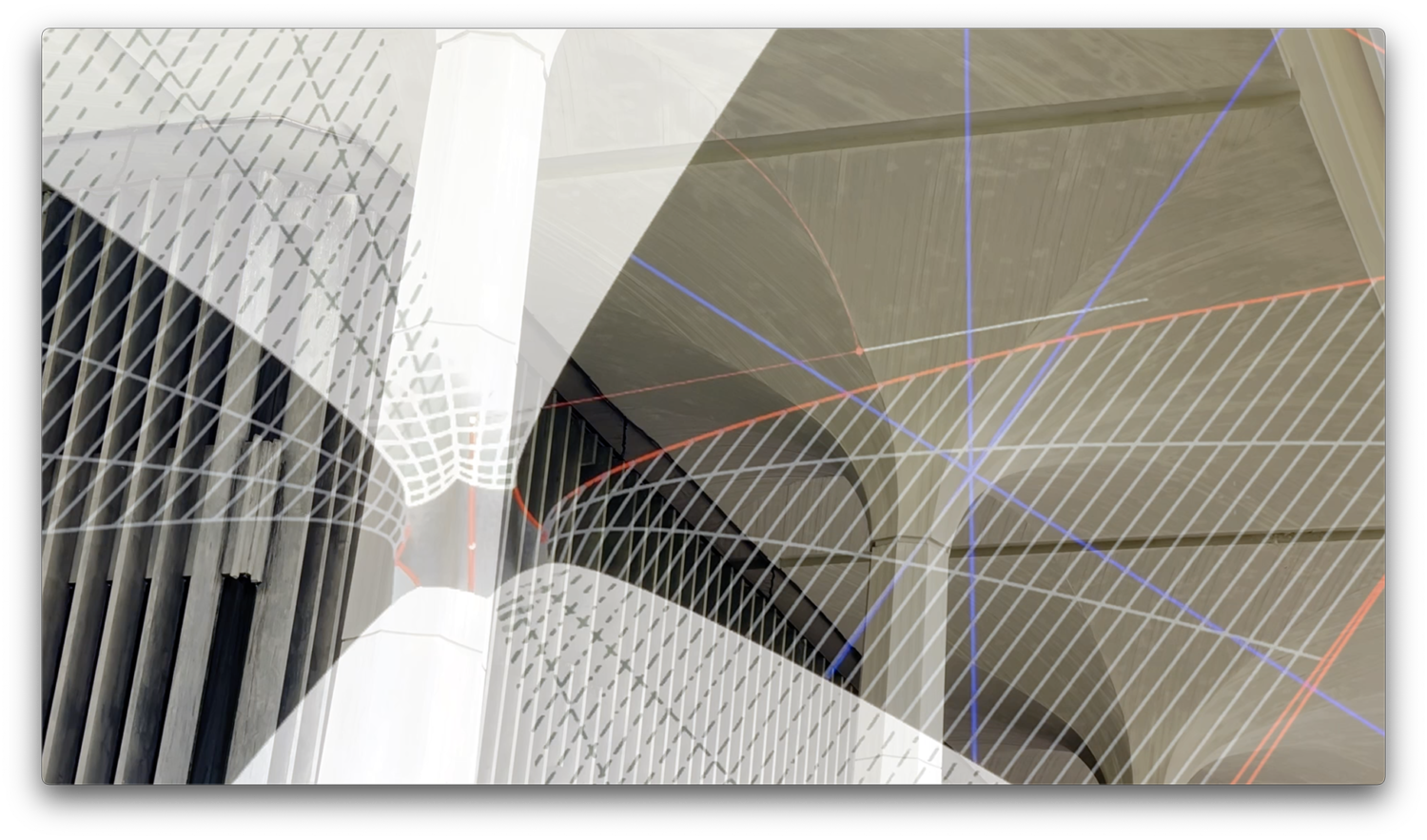

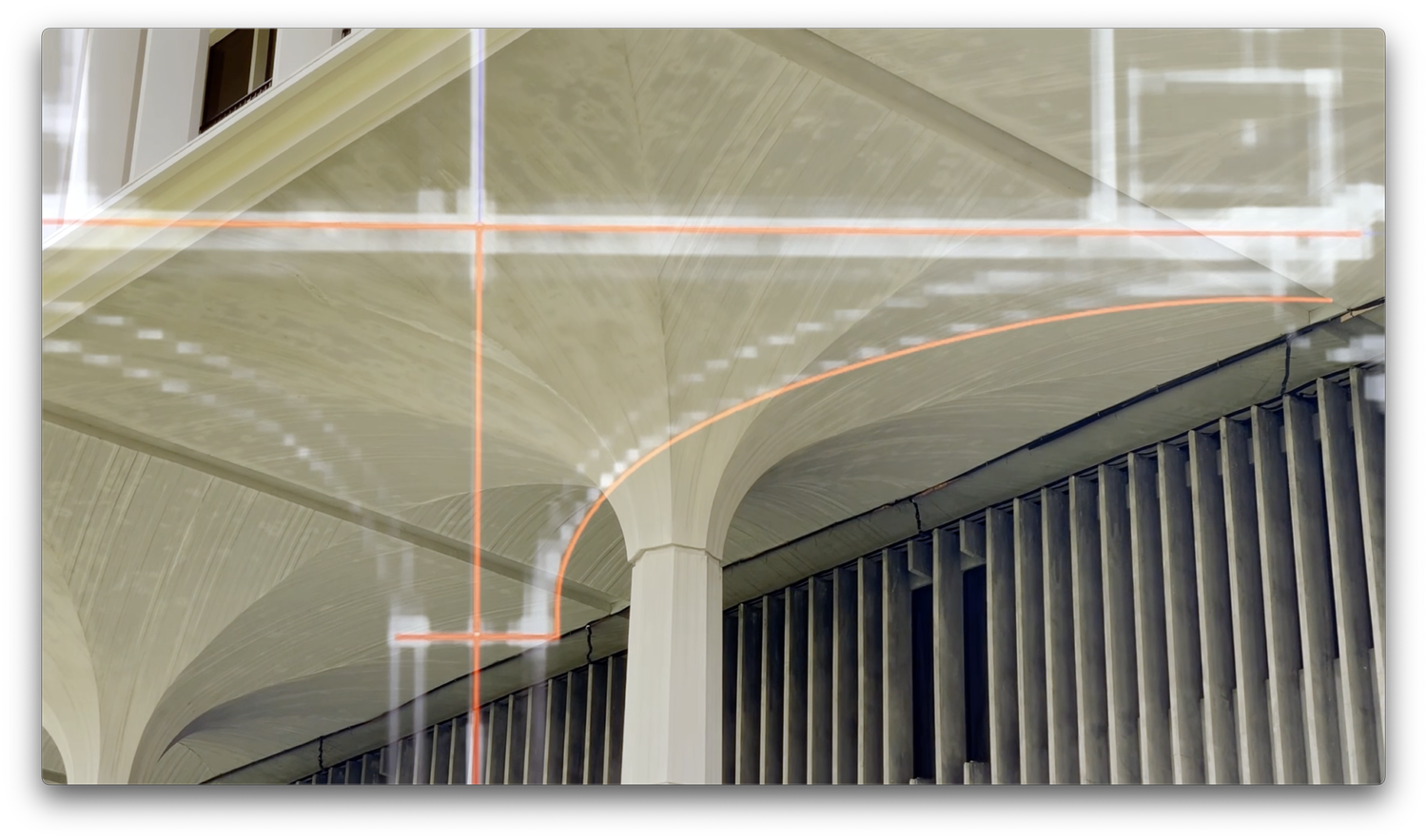

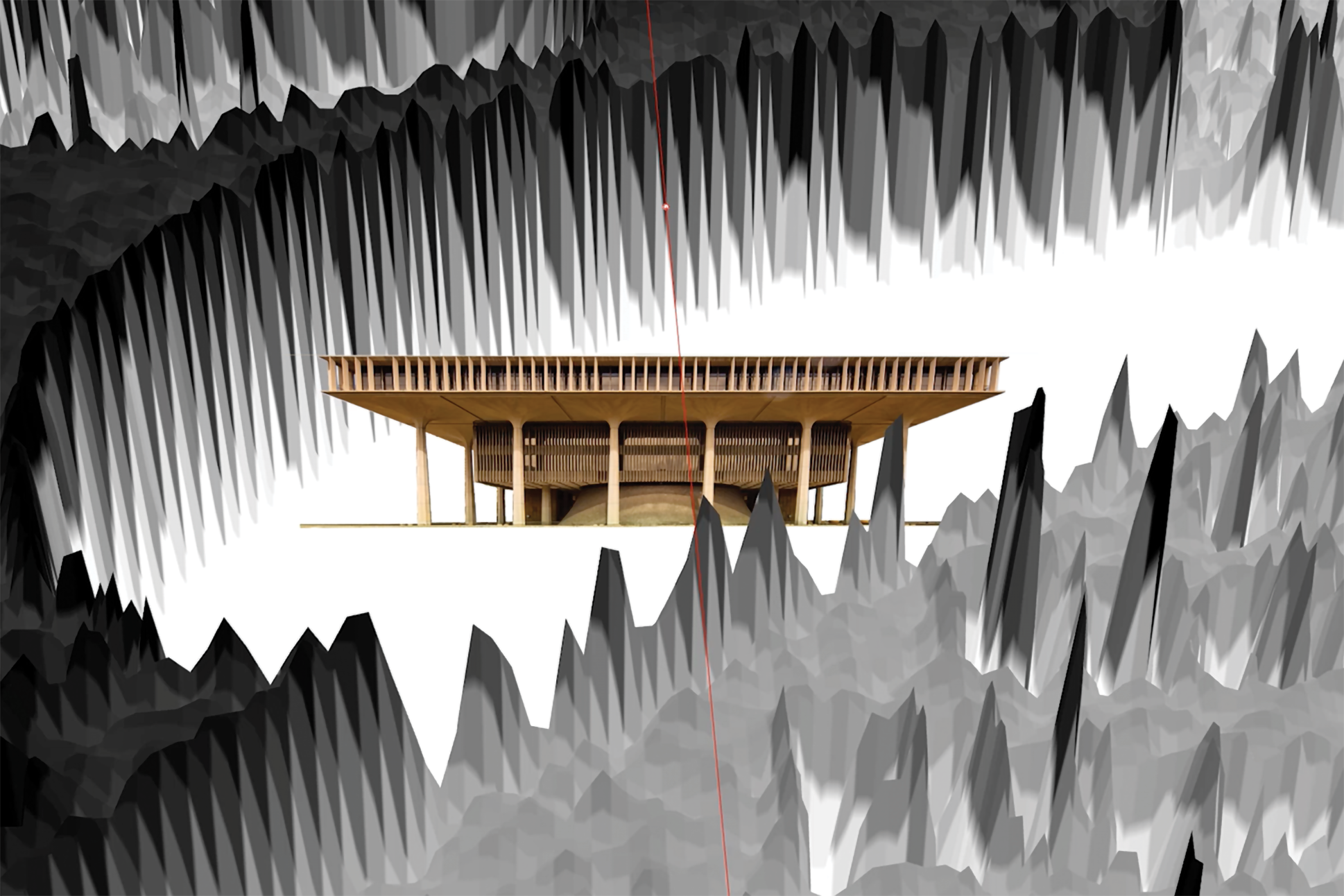

One of their first collaborations outside of the classroom is an experimental short film whose tone and visual style blend documentary and horror. Titled “A Justice-Advancing Architecture Tour,” the film juxtaposes the Hawaiʻi State Capitol Building—“the single-most dominant work of public architecture in the state of Hawaiʻi,” according to the National Register of Historic Places—and ʻIolani Palace, the seat of Hawaiʻi’s monarchy until the Overthrow in 1893 and at the time one of the most advanced buildings in the world.

What begins as a diagrammatic dissection of the capitol building’s design, complete with slow pans worthy of the most polished architecture documentary, devolves into a hallucinogenic meditation on death, dispossession, and cultural erasure. “Contrary to popular architectural interpretation and belief,” Connelly intones, “the Hawaiʻi State Capitol Building isn’t just modernism. It’s militarism. It’s desecration.”

The Hawaiʻi State Capitol Building isn’t just modernism. It’s militarism. It’s desecration.

Sean Connelly

Foundational to Hawaiʻi Non-Linear’s approach to architecture is the notion that history is ever-present. The name is a nod to Hawaiian cosmology and to the concept of time as a fluid, folded, and fungible thing. Through this lens, the U.S. military’s occupation of Hawai‘i is not in the past but rather exists continuously, dynamically in the now. The same is true of ‘āina’s own memory of a time precontact—divergent realities that coexist simultaneously, to be acknowledged, resisted, or coaxed back into being.

Through its work in and outside of the architecture profession, Hawaiʻi Non-Linear is attempting to make visible—and real—the latent futures that exist all across Hawai‘i. It’s a project with global significance, Leong says. “Hawaiʻi is such an acute example of settler colonialism and these larger patterns that get played out all over the place. That’s why Hawaiʻi is so important to understand on a global level.”