Political change depends on getting people to see a story the same way. This stubborn truth frustrates activists who seek justice by reimagining and reclaiming Hawai‘i’s maps.

Two weeks after the 80th anniversary of the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the U.S. Navy announced that 19,000 gallons — 5,000 more than an earlier figure — of fuel mix spilled downhill from its Red Hill Bulk Fuel Storage Facility in Honolulu. The facility’s 20 underground fuel tanks, built a 100-feet above a major aquifer during the Second World War, were known to leak. Military and civilian families alike were turning on their taps and smelling fuel. Those who drank or showered in the water suffered rashes, sores, stomach aches, and nausea — about 2,000 people reported falling ill. More than 3,000 military families left their homes for temporary lodging in hotels. Honolulu shut down three drinking wells, fearing contamination. In March 2022, following mounting criticism, and after the Navy vacillated on whether to fight the state in court, the Pentagon announced it would close the facility permanently. By April, however, there was still no consensus between the Navy, academics, and regulators about where the contamination was moving.

The plot advanced in numbers. The setting was infrastructure — underground pipes, wells — and the characters were bureaucrats, institutions, and victims. Ours is a purportedly secular society, and drinking fuel-contaminated water harms people no matter what they believe. But throughout the fuel leak crisis at Red Hill, the area originally known as Kapūkaki, a necessary context seemed absent. The landscape of Hawai‘i is woven with mo‘olelo, or orally transmitted stories, that store generations of knowledge and patient, detailed observations of the natural world.

I hoped one of these stories might reveal what more was at stake, and the mo‘olelo of Keaomelemele presented an image of a miles-long path packed bumper-to-bumper with 30-foot-long lizard deities, known as mo‘o, migrating from the North Shore to Honolulu. The story of mo‘o migration was a record of a changing climate, according to University of Hawai‘i Mānoa English professor Candace Fujikane. “The arrival of the mo‘o signals a historic moment when Kānaka Maoli began to pay greater attention to the care and conservation of water and the cultivation of fish,” Fujikane writes in Mapping Abundance for a Planetary Future: Kanaka Maoli and Critical Settler Cartographies in Hawai‘i. With that new concern for water, Kānaka Maoli could imagine in the migration of the mo‘o a network of waterways above and below ground, connecting the land’s far-flung ecosystems. These deities became known as guardians of streams, springs, and fishponds. “Today, it is at Kapūkakī that the mo‘o engage in battle with monsters that lie beneath the surface of the land,” Fujikane writes.

***

I had first encountered Fujikane’s work in college. Asian Settler Colonialism, a collection of essays she co-edited and wrote the introduction to, explored how Asians have helped develop Hawai‘i as a “U.S. colony” through the state legislature, prisons, the military, and the arts. Fujikane, who was born on Maui, calls herself a “fourth-generation Japanese settler aloha ʻāina.” I had followed Fujikane’s output since reading the collection, and I thought that Mapping Abundance, published in 2021, might illuminate the Red Hill spill.

In Mapping Abundance, Fujikane recounts the past decade of activism in Hawai‘i, chronicling attempts by developers and the occupying settler state to “wasteland” the aina — framing it as lacking all but a potential for development — while activists including herself fought to reveal those lands’ abundance. Yet she finds opportunity in others’ apocalypse. The current way of seeing land through “cartographies of capital” — expedient abstractions of complex lands for profit — facilitates the extraction and pollution driving climate change, she writes. And yet, climate change heralds the end of capital, she further explains, “making way for Indigenous lifeways that center familial relationships with the earth and elemental forms.”

In several episodes where capital — developers, the state — depicted lands as scarce, the activists deployed “Kanaka Maoli and critical settler cartographies” to find what the land could provide in not only food and water but also wonder and hope. Sometimes that’s literal, and sometimes that’s identifying the elemental forms of nature, the akua, which, Fujikane writes, “were identified and named based on the ancestral insights into the optimal workings of interconnected ecological webs.” Just as the developer tells a story of a purported wasteland to develop it, activists tell a story of abundant land to preserve it.

Like any story, learning from mo‘olelo requires some to suspend disbelief. Mo‘olelo are rife with double meanings and double entendres. They aren’t always what they appear to be. Seeing these stories come to life in the landscape requires some degree of imagination. One story Fujikane calls a “genre of wonder” encourages “listeners to challenge the limits of our conceptions of what is possible and to deepen our imaginative capacities.”

Mo‘olelo are rife with double meanings and double entendres. They aren’t always what they appear to be.

And yet, political change depends on getting others to see a story the same way. Fujikane devotes a chapter to demonstrating how this stubborn truth frustrates her careful methods. In 2010, local activists protested the proposed development of an industrial park in Wai‘anae on O‘ahu. Locals argued that the development, ignominiously named the Purple Spot, would open the door for yet more development, inevitably eroding their agricultural district. They also worried it would desecrate the storied birthplace of Māui, the supernatural being who pulled the islands from the ocean’s depths with a fish hook.

The dispute evolved into a contested case before the state Land Use Commission. In the commission hearing room, the developer’s attorney presented a five-gallon-bucket of the land’s rocky soil to suggest that the land wasn’t good for farming. In Fujikane’s eyes, he reduced complex, storied lands to merely “dirt held in suspension, isolated away from the histories, stories, material practices, and people of the place from which the dirt was taken.” The developer’s view of the land relied on “stark line drawings paralyzed in time” that “abstract, compartmentalize, and encode the intimacies of land into a ‘parcel’ and a ‘project area.’”

As a counterpoint, the activists projected onto the wall of the hearing room photographs from 1968 of the land’s bounty: farmers held watermelons in green fields. In her own testimony, Fujikane presented maps issued by the Land Study Bureau in 1972 that show the land in rows of green. The visuals showed that the developer assessed the land in its unirrigated state to prove it was “unproductive.”

The developer was also required to commission “cultural impact assessments,” which resulted in an 11-page evaluation for the property itself and a 145-page evaluation for the surrounding land that contains places described in the Māui mo‘olelo. Comparatively, according to the developer’s reductive argument, the page numbers of these assessments — 11 versus 145 — suggested the proposed development was less culturally relevant than its neighboring plots. But in isolating the land from its surroundings, the developer was practicing what Fujikane calls “a settler mathematics of subdivision.”

Testifying against the development, one local asserted, “These boundaries were not known to our ancestors.” In her own research outside of the hearing room, Fujikane had been sifting through maps of land commission awards from 1851, where she noticed the term “mo‘o” cropping up. It was a shorthand for “moʻoʻāina,” smaller land sections connected within a larger land base, “genealogically connected to one another across ahupuaʻa, as the long iwikuamoʻo (backbone) formed by the moʻo akua in Moʻoinanea’s genealogical line,” Fujikane writes. Like the waters coursing away with fuel spilled from Red Hill, these lands too were connected.

The developer’s attorney asked for documentation of Māui’s exact birthplace. The meaning of the mo‘olelo, however, is not always forthcoming from text alone, Fujikane writes. On a kūpuna-led bus tour through Wai‘anae, Fujikane witnessed the Māui mo‘olelo come alive as she moved through the landscape. Driving along Farrington Highway, an elder located Māui’s evolution — hatching from an egg as a chicken then evolving into a manin the landscape. The elder identifies Pu‘u Heleakalā as “an egg lying on its side,” then “two peaks that form a beak emerge as a chick hatches from the egg,” Fujikane writes. Turning up toward the mountains, “the silhouette of a beaked man with a wattle” appears, she writes. “As we continue up Hakimo Road, the silhouette finally transforms into the rugged facial planes of a handsome man.” Māui’s exact birthplace, in other words, was all around, visible in full only by traversing the land.

The elder explains, “One thing about Waiʻanae is we want to save our view-planes because that’s where our stories are.” With her cultural memory stored in the mountains themselves, each glance renews the mo‘olelo told long before. One night, under a full moon, the elder took Fujikane to Hakimo Road to look at the profile of Māui. “Oh, look at him!” the elder says. “He is one handsome brotha, you know what I mean?”

Beyond the military complex’s carbon copy housing, the barbed wire, the pavement, and the city buildings, I wasn’t sure I could make out what came before, what was lost and being lost.

The development was eventually called off over an issue about an easement rather than the cultural grounds the activists argued. A Judas had emerged in the form of a cultural practitioner who stood to profit from a community benefits package and claimed that the land was, in fact, a wasteland. “And because of this testimony the land use commissioners asserted that there was ‘no consensus’ on the significance of that land,” Fujikane writes.

Legally, the state isn’t built to buy in either. Fujikane later describes the contested case against the construction of the Thirty Meter Telescope on Maunakea, when activists attempted to make Mo‘oinanea, the mo‘o matriarch deity, a legal party. They claimed she dwelt on Maunakea and therefore had a vested interest in the land. The Bureau of Land and Natural Resources denied the request. “The information provided indicated that Moʻoinanea is a spirit, not a person, and as such does not meet the requirements of Haw. Admin. R. §13-1-31 and 13-1-2 to be admitted as a party,” the bureau wrote in a resolution. (According to the latter law, “person” includes corporations and other organizations. Four decades ago, another non-human resident of Maunakea, the palila, an endangered native bird species, sued the Department of Land and Natural Resources for letting goats and sheep eat the last of its habitat. The bird, represented by the Sierra Club, won.)

***

On a Tuesday in December 2021, I took a bus to Hickam Air Force Base, where the water was reported to be contaminated. The bus slowed to a halt at a checkpoint, and a man in uniform stepped aboard and asked me for my military identification (non-existent). I flashed my driver’s license, he shook his head, and I shrugged and walked out of the checkpoint. I was there reporting a story about Red Hill’s fuel contamination crisis, trying to get a feel for the scope of the issue, but also its more lasting environmental, cultural, spiritual — call it what you will — impact on the island. Pinching my way through Google Maps, though, I could see no subterranean network of water running throughout Honolulu, no obvious signs of meaning that others before me had found in the land.

The date — still alive in infamy, depending on whom you ask — was December 7th. The same day 80 years before, Japan attacked American territories throughout the Pacific including, infamously, Pearl Harbor. That morning I walked around the memorial, which was populating with visitors in veteran’s hats. Although the attacks occurred on the same day, the Pacific Ocean straddles the international date line: December 7 in Hawai‘i was December 8 in other regions that Japan targeted. In an earlier draft of the speech he would give to Congress, President Franklin Roosevelt framed the main attacks as a “bombing in Hawaii and the Philippines.” I had originally learned this from the historian Daniel Immerwahr’s book, How to Hide an Empire. Now there it was on an 80-year-old typewritten draft in a glass case at the memorial: Roosevelt drew a pencil through the two names and wrote “Oahu.” By the time he spoke, he called it “the American island of Oahu.” It was a presidential act of cartography — zooming in and cropping to a limited geography and chronology — that determined what would be remembered to this day. Perhaps remembering the same-day attacks on Pearl Harbor and the Philippines and Midway Island and Wake Island and Guam (and a host of British colonies including Hong Kong) would have proven too cumbersome, or just narratively inconvenient. The rest of that morning, I walked through an old submarine and chatted with dewy-eyed veterans. In the gift shop sat a stack of facsimile St. Louis Star-Times newspapers dated Monday, December 8, 1941. The headline: “WAR DECLARED.”

Two months later, I spent a night on Hawai‘i Island, on the black lava fields south of Pāhoa. Lava undulated from the volcano to the water thirty years before, and now only spare ʻōhiʻa and other shrubs grew from the soilless, newborn land. I stayed in a plywood bed and breakfast on stilts over bare rock, in a neighborhood of other Burning Man-esque hippie cottage-compounds. I was chuffed to find W. G. Sebald’s novel Austerlitz on a communal bookshelf, sandwiched between a perplexing combination of woo-woo tomes on magical thinking and Ayn Rand. I couldn’t help imagining the land of Red Hill, missing its context and memory, as I read Sebald’s narrator recall a map of a Nazi prison camp. He contemplates that “everything is constantly lapsing into oblivion with every extinguished life, how the world is, as it were, draining itself, in that the history of countless places and objects which themselves have no power of memory is never heard, never described or passed on.” There it was, a danger of forgetting.

Later in the novel, the titular character imagines what existed where a London train station stands: “The little river Wellbrook, the ditches and ponds, the crakes and snipe and herons, the elms and mulberry trees…had all gone…and gone now too are the millions and millions of people who passed through…day in, day out, for an entire century.” Dwelling in that place, recollecting, he says, “I felt at this time as if the dead were returning from their exile and filling the twilight around me with their strangely slow but incessant to-ing and fro-ing.”

Back on Oahu in December, I left the Pearl Harbor memorial in an Uber headed downtown. The driver asked why I was in town and then offered a detour. He pulled up to the entrance to the Aliamanu Military Reservation, a housing development downhill from the leaking fuel tanks, where the water was later found to contain levels of petroleum hydrocarbons three times the state limit. Its resident military families were relocating to hotels in Waikiki. A guard stopped the car (“unusual,” the driver said). A few dozen yards inside, an electronic sign was flashing: “Do Not Use The Water!” The guard turned the valiant driver away, and back we went down into Honolulu.

Beyond the military complex’s carbon copy housing, the barbed wire, the pavement, and the city buildings, I wasn’t sure I could make out what came before, what was lost and being lost. I couldn’t make out the stories of the land’s former Hawaiian inhabitants, though another story — secular and grandiose — was already shaping the people here. The dead, albeit of a different demographic, were returning too.

I stayed on in Honolulu until evening to watch the hullabaloo before a commemorative parade at Kapi‘olani Park: Hundreds of red-white-and-blue cheerleaders flown in from the mainland, grade-schoolers-in-uniform, slack-jawed and dozing nonagenarians-in-uniform receiving yet more medals on stage. (“Everybody is still receiving a medal!” the master of ceremonies said, after thanking the event sponsor, the History Channel.) On the grass sat a two-story inflated Purple Heart float, a blow-up Navy jet bigger than a bus, a 20-foot-tall eagle with stars-and-stripes wings, and 12-foot balloons for the military’s branches. Here was a narrative complete with characters and gods, a mythology all its own. I wouldn’t know where to begin reconstructing what came before, but I could almost imagine the raw land and the people passing through here long ago, in the time between pure lava and this.

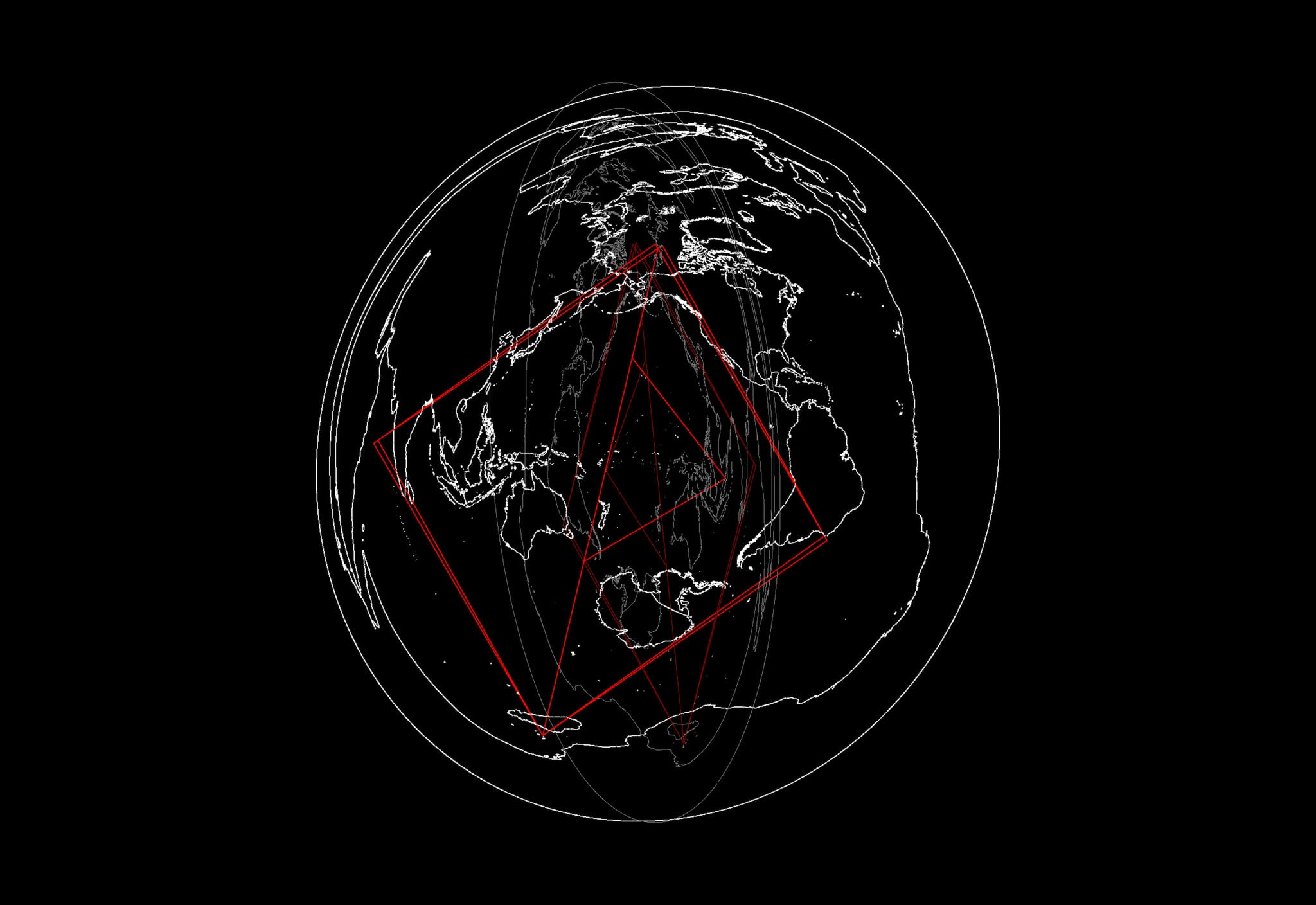

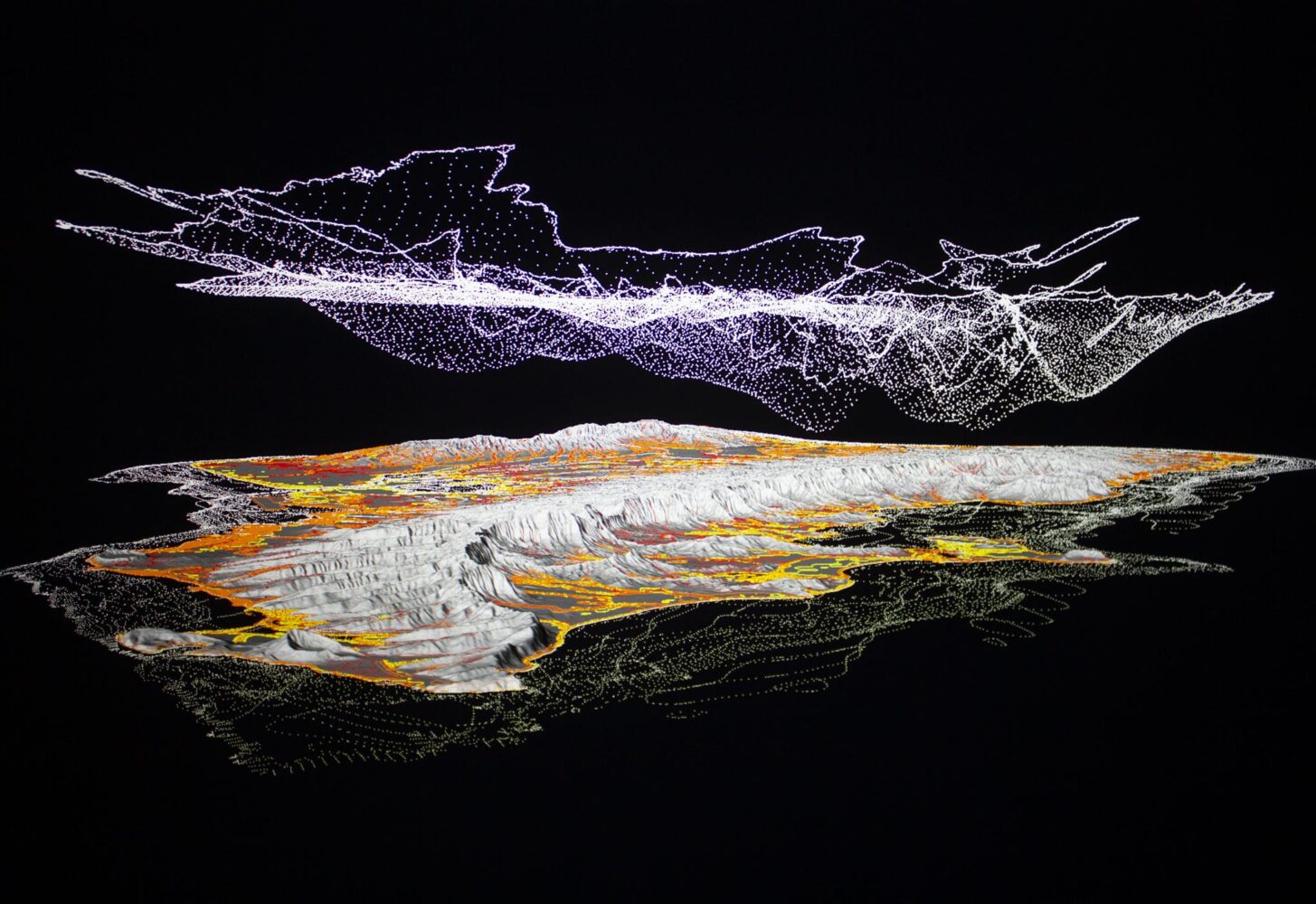

About the Artwork

All digital architecture models by artist Sean Connelly, who works primarily in architecture, sculpture, and experimental cartography. All stills by film collective kekahi wahi (Sancia Miala Shiba Nash and Drew Kahu‘āina Broderick), who document stories of transformation across Hawai‘i.

This feature appeared in the Fall/Winter 2022 issue of Flux Hawai‘i.