In his debut novel, the Honolulu author confronts imperial legacies in Hawai‘i and Korea with humor and heart (and phantom spirits).

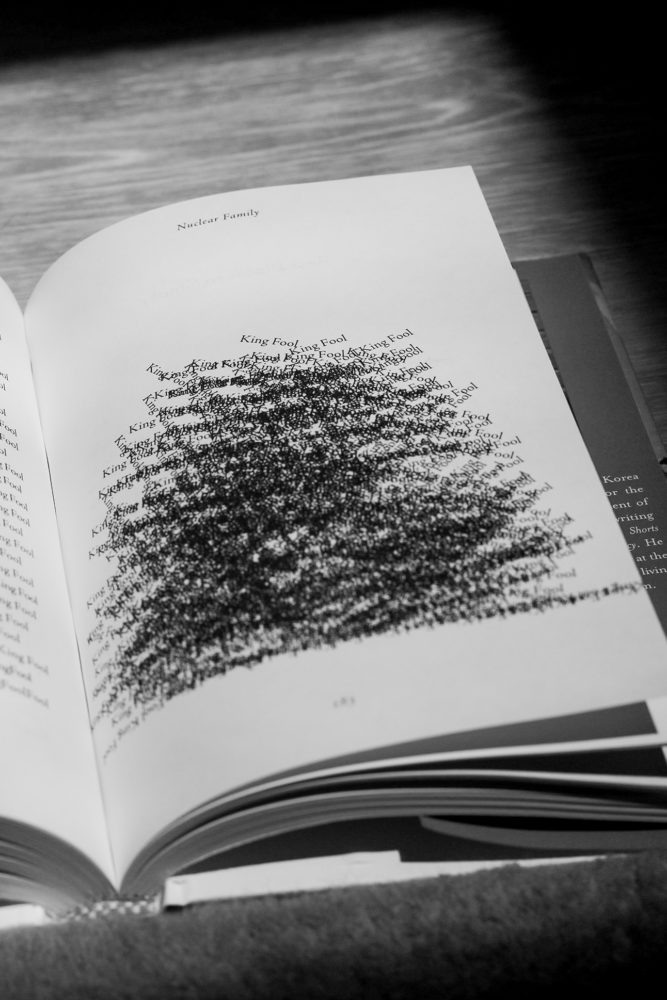

Nuclear Family, the debut novel by Joseph Han, is many things: a ghost story embedded into a multigenerational Korean family saga; a typographical experiment utilizing elements of concrete poetry; a reckoning with the U.S. military; a lowbrow stoner comedy. But don’t call the book, which takes place largely in Hawai‘i, a beach read, with all the genre’s connotations of escapism. Han, a National Book Foundation “5 Under 35” honoree, says he thought a lot about the words readers use to describe their favorite books: It was so immersive; I felt transported; I escaped into the text. But that impulse felt complicated by writing about a place so often framed as an idyllic escape for tourists. Or, as Han explains, “I was very wary of allowing readers to visit the Hawai‘i in their imaginations.”

So instead of Hale‘iwa, or Waikīkī, or Kailua—places that favor the postcard image of Hawai‘i—Nuclear Family takes readers to Ke‘eaumoku Street, where “somewhere in the middle,” Han writes, “between a strip club and Ala Moana Center on the other end, bloated with a Target, a Walgreens, and a Walmart on each block,” sits Cho’s Delicatessen. It’s an unremarkable Korean plate lunch spot, with styrofoam plates that squeak under the weight of banchan, until it’s anointed by a visit from Guy Fieri, America’s “diner troll,” Han pans. Fieri’s co-sign elevates Cho’s Delicatessen into a bustling franchise, with lines suddenly out the door. But many years later, Umma, the family matriarch, still harps on one detail from his visit: “He didn’t even pay for his food.”

It’s funny, but at its heart Nuclear Family is about the many fractures, fallouts, and fissures caused by war. The Cho family—Umma and Appa and their children, Jacob and Grace—are Korean immigrants living in working class Honolulu. When Jacob, a closeted 25-year-old, leaves Hawai‘i for South Korea to teach English, his parents are elated. “Your Korean is going to get so good!” Umma exclaims. But then Jacob gets possessed by the spirit of his dead grandfather (hate when that happens) who’s desperate to reunite with the family he abandoned in North Korea. A viral video of a possessed Jacob unsuccessfully attempting to cross the demilitarized zone into North Korea sends shockwaves across the Pacific, bringing shame to the Cho family. Business slows, as Grace, a 21-year-old senior at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, tries her best to remedy the PR crises. She copes primarily through smoking an increasing amount of weed, which leads to one particularly extravagant meal at Zippy’s.

Throughout the book, O‘ahu’s housing crises, Red Hill’s jet fuel leak, and development on Kānaka Maoli burial grounds are all alluded to, grounding Nuclear Family in a socio-political present that places the concerns of Hawai‘i residents at its core.

“You’d have to visit Cirque du Soleil to see someone juggle as much as Han with such effortless dexterity and tenderness,” writes a critic for The New York Times. But for Han, that balancing act felt instinctual. He sees parallels to the structure of the plate lunch, a culinary mishmash often posited as a metaphor for local culture: the best of everything. “And that kind of informed how I approached writing the book, offering a little bit of everything in terms of style, and point of view, and also different genre registers,” Han says. “In writing in all these different genres, I was really just trying to create the language that I needed to survive as an artist.”

He was also inspired by the Korean ceremony known as jesa, in which a large table is set with an overflowing assortment of foods as an offering to those who’ve passed. “So much of the novel is about how our nourishment is so conditioned on how well fed our spirits are,” Han says. He’s come to think of the writing of Nuclear Family as its own elaborate ceremony, a table he’s returned to over and over again to bear the weight of his ancestors, and to offer them something in return. “I needed the novel to structurally be able to hold as much as it could,” he says.

In writing in all these different genres, I was really just trying to create the language that I needed to survive as an artist.

Joseph Han

Han, 30, was born in Seoul and moved to O‘ahu with his grandmother, a devout Christian, when he was a baby (his parents eventually followed as he was about to start high school). Because he was born prematurely and prone to sickness as an infant, “my grandmother frames my life [as] having been saved by God,” Han says, with a chuckle. “And that’s why they needed to protect me, by finding a healthier environment for me [in Hawai‘i].” He grew up in Honolulu, in low-income housing on Vineyard Boulevard, feeling like an outsider. At Hawai‘i Baptist Academy, where Han graduated, he was bullied, his Koreanness most legible either through the specter of North Korea or food. Though his mostly Japanese classmates “loved meat jun, they ridiculed me for being Korean, for my appearance and my flat face,” Han writes, in an essay recently published in LitHub titled “Making Meat Jun, Facing History: Flattening Korean Tradition in Hawaiʻi.”

It wasn’t until college, at UH-Mānoa, that Han began to conceive of himself as a writer. Up until that point, he describes his attitude towards the themes guiding his work today— reckoning with the U.S. military occupation globally; the histories shaping the Korean diaspora—as “totally detached, oblivious, and indifferent.” But during his sophomore year, Han’s father, a taxi driver at the time, was assaulted by a soldier in the military who refused to pay his fare. “That was a really formative moment for me,” Han says. “That anger that I felt and seeing my dad in the hospital really started to feed a lot of my wanting to learn more about military violence, both here in Hawai‘i and Korea.”

Reading scholars like Haunani-Kay Trask and Grace M. Cho radicalized Han, shattering the narrative he was taught growing up of the U.S. as the world’s savior. Just as enlightening was discovering the world of Asian American literature, and Korean American literature in particular. These books oriented Han towards the possibilities of using fiction to illuminate histories that were either silenced in his family or distorted by the weight of American exceptionalism. In this way, Han’s project is somewhat of an ouroboros: “That’s what I have to offer,” he says, “to use fiction to write back against fiction.”

Nuclear Family, which Han began conceiving in 2017, towards the end of his research as a PhD student (also at UH-Mānoa) comes at the tail of what he calls a “huge learning curve.” He is both realistic about and resistant towards what it means to be a writer from Hawai‘i who’s writing about Hawai‘i within a national framework. He intentionally wrote Guy Fieri into the book as a hook for readers from the continental United States, “which really worked out, as I’m seeing now,” Han says, referring to the book’s Fieri-heavy press coverage. “Maybe a little too well.” And yet the book rarely panders to an outsider’s gaze, referencing menehune, Puck’s Alley, and iwi kūpuna without an explanatory comma in sight. Foremost, though, Han says he felt “a huge responsibility” to write for a diasporic Korean audience.

It’s a responsibility he’ll carry into his next book titled Monster House. Han describes the collection of short stories as even more personal than Nuclear Family, while taking a broader look at the Korean diaspora in Hawaiʻi. In the meantime, he has shifted into more of a mentor role, serving as an editor for the West region of Joyland Magazine, a literary journal that publishes by time zone, and teaching a fiction workshop this summer at Antioch University’s MFA program, where he was paired with five mentees.

Writing fiction, though, continues to be Han’s primary focus, grounding him in a sense of place—a respite for someone who’s “always felt in-between in a way, neither of Korea or Hawai‘i,” he says. Rather than fight that in-betweenness, Han has learned to see it as a unique vantage point for his work, a kind of homecoming. “Fiction became a home for me, a place where I can return to articulate the important connections that continue to shape who I am and what I live for,” Han says, “and a lot of that comes back to living for the opportunity to reconnect with those we’ve lost or forgotten.”