Hawaiian Home Lands are meant to generate Native Hawaiian self-sufficiency, yet at Kailapa on Hawai‘i Island, Kānaka residents are awfully overcharged for freshwater.

Images by Nani Welch Keli‘iho‘omalu

The view from Kailapa, the Hawaiian homesteads community on Hawai‘i Island’s leeward side, is remarkable not because of what you see but because of what you do not. No buildings on the makai side of the highway obstruct the panoramic view of the Alenuihaʻa Channel. Here, the water is a shade of blue so dark that you almost sense the 6,000-foot chasm between the churning ocean surface and the sea floor. Annie Kahikilani Akau, a native daughter of Kawaihae, named the subdivision Kailapa, meaning “lapping waters,” for the waves that hit the cliffs during high surf.

On land, what you do not see is a diversity of plant life. Instead, the two dominant species kiawe and buffelgrass, drought-tolerant vegetation introduced to Hawaiʻi in the 1820s and 1930s respectively, have replaced the area’s bountiful native dry forest. In 1913, botanist Joseph Rock was dazzled by the biodiversity of Hawaiʻi’s dry forest regions because it was “in these peculiar regions that the botanical collector will find more in one day collecting than in a week or two in a wet region.” On his tour of Hawaiʻi Island, Rock found himself upslope of where the Kailapa community is today, already beginning to note the extinction that was taking place. “Three miles south of Waimea, the land is known as Kawaihaeiuka, and must have been once upon a time covered in a plant growth similar to Puuwaawaa now,” he observed in his field writings. “In fact, the land is now very open and only a few trees can still be found, cattle having destroyed them very rapidly.”

In Kailapa there is not much soil left to see, either. When cattle chomp and stomp plants, saplings are unable to take root. Bare soil slips off the steep mountain slopes. Today, two thin layers of material above the bedrock of Kailapa consist of mostly pebble fragments and dead grass that has yet to blow away. A 2006 study of the area’s soils concluded that the severe nutrient losses “likely result from the strong downslope winds that can carry dead plant material, litter and/or ash into the adjacent ocean.” This fierce wind, called Mumuku, can also mean amputated, mutilated, or maimed.

Brandy Oye is familiar with this Mumuku wind. She was in high school when her father took her to visit the family’s lot in Kailapa in 1990. Under the blazing sun, he drove Brandy in their four-by-four pickup down a rutted dirt road past one of only two residences at the time, that of community stalwart Jojo Tanimoto.

“I remember passing Aunty Jojo’s house and I thought, ‘Where is Dad’s lot, and how do we know?’ Because there was no road. It was just offroading until Dad said, ‘Right here! This is it!’” Oye remembers. “And it was just red dirt and a flag pin.”

Teenaged Oye was dismayed. “I thought, ʻWhere are we?’ It was just red dirt and boulders.”

Oye was on the empty lot of what was to be her family’s home.

The 10,153-acre Department of Hawaiian Home Lands Kawaihae parcel, in which Kailapa sits, encompasses the entire ahupuaʻa of Kawaihae I. With an average annual rainfall of 120 inches in the forested mauka portion and around 5 inches at the coast just 7 miles away, this ahupuaʻa boasts one of the most magnificent rain gradients in the world. But you wouldn’t know it by the cost of water at the Kailapa homestead. Today, rates are over six times Hawai‘i county’s rates, and are slated to increase by 400 percent before the decade is out. The freshwater system that was meant to be a temporary solution has now been in place for more than 25 years. In addition to the exorbitant water bills, Kailapa residents face water insecurity.

The Hawaiian Homelands Commission is a Hawai‘i state agency regulated by the Hawaiian Homes Commission Act. The HHCA is a U.S. law that “provides direct benefits to Native Hawaiians in the form of 99-year homestead leases at an annual rental of $1.” It was passed in 1921 when Hawaiʻi was a territory. After Hawaiʻi joined the union in 1959, the responsibility for administering the law was transferred to the state; today, it is the responsibility of the nine-member, governor-appointed, Hawaiian Homes Commission. The commission also oversees the Department of Hawaiian Home Lands, or DHHL, which is the larger state organization responsible for most day-to-day management of the land trust. The reason the trust exists at all is largely due to the efforts of Jonah Kūhiō Kalaniana‘ole, a forward-thinking Hawaiian prince.

land back

By the time a 49-year-old Kalaniana‘ole introduced the HHCA, which he would spend the remaining years of his life working to pass, he had already witnessed the overthrow of his kingdom and spent a year in jail for joining the forces who attempted a counter-revolution. The busy, globe-trotting aliʻi had introduced surfing to California, fought in a war in South Africa, and been sent, as a boy, to Japan for a year in hopes of being married off to Japanese royalty. By 1920, Kalaniana‘ole was a veteran delegate to the United States Congress when he testified before a full U.S. House of Representatives in Washington D.C., explaining why a Kānaka rehabilitation program was imperative.

“The Hawaiian race is passing,” he said. “And if conditions continue to exist as they do today, this splendid race of people, my people, will pass from the face of the earth … The legislation proposed seeks to place the Hawaiian back on the soil, so that the valuable and sturdy traits of that race, peculiarly adapted to the islands shall be preserved to posterity.”

Hawaiian extinction was not hyperbole. As many as 800,000 Hawaiians lived and flourished across the pae ʻāina in the year 1779. Fifty years later, due to virulent diseases introduced by early European voyagers, that number had plummeted to around 130,300. A Hawaiian teenager in 1800 could have watched something like 75 percent of her people perish, if she was lucky enough to survive into her 70s. By 1919, the number of Hawaiians was 22,500. Hawaiian Homesteads would not be a nice thing to have — it was imperative. But with no voting power in Congress, Kalaniana‘ole compromised, bending to the demands of the sugarcane and ranching lobbyists working to protect their land and capital. With each compromise, the bill was revised and rewritten to tip the scales in favor of big business. When the final version of the HHCA bill passed, it was a shattered and reassembled vestige of Kalaniana‘ole’s original dream of prosperity for his people.

While the law ultimately did dedicate land and resources to Hawaiian homesteading, two major provisions have always stymied successful implementation of the homesteading program. One revision required potential beneficiaries to have the settler-imposed idea of 50 percent Hawaiian blood quantum in order to receive leased land. The other revision severely limited the type of land that would be made available for homesteading.

In the Kailapa subdivision, water rates are over six times Hawai‘i county’s rates and slated to increase by 400 percent before 2030.

The revised language of the HHCA made sure that “all cultivated sugarcane lands” be excluded from consideration. The exemption of sugarcane land along with “all lands within any forest reservation” meant that hundreds of thousands of some of the most farmable land was off the table. In 1900, sugarcane fields comprised 100,000 acres of land in Hawaiʻi. By 1941, that number had exploded to 238,000. Hawaiian homelands would have to be scraped together from the assortment of leftovers that sugar barons wouldn’t even attempt to plant.

Agricultural expert Albert Horner submitted written testimony to congress regarding the fourth version of the bill. He opened his letter by scolding the integrity of the legislation: “If this bill was conceived in honesty of thought and purpose,” he wrote, “those behind it would have selected lands better adapted for the purpose than are those named in the bill.” He went on to catalog all proposed homestead land and describe exactly how each parcel was unsuitable for homesteading. In his conclusion, Horner stated, “You will note that all ‘cultivated sugar-cane lands’ are excluded from ‘available lands’… thus confining the lands available for the rehabilitation project to those upon which it is not possible for the Hawaiian or anyone else to make good. In short, it gives the plantation all arable and the Hawaiians all arid lands.”

Despite the shortcomings of the HHCA, the bill did pass, and 203,500 acres were set aside in hopes of turning marginal land into fruitful homesteads. In a speech Kalaniana‘ole delivered less than a year prior to the bill’s passage, we can hear him gripping on tightly to the hope of a successful homestead program: “This will save the Hawaiian people from being a dead race. . .” A parched Kawaihae was a significant parcel of Hawaiian homesteads’ waterless acreage.

the luck of the drill

The DHHL Kawaihae property was initially explored for development in the late 1960s. At that time, the only paved road with access to the property was Kohala Mountain Road, which sits about 3,000 feet above sea level. Potable water is needed to develop any homestead, so in 1969, the State Division of Water and Land Development investigated diverting water from the former Kehena sugarcane ditch above Kohala mountain road and piping it down to the property. The resulting study revealed a historically intermittent and unreliable flow of ditch water. Additionally, with the Clean Water Act of 1972 soon to be passed, the law would require a treatment facility for the distribution of raw ditch water. With an unreliable water source and a high project cost, the idea was scrapped.

Kawaihae was explored again for development in the early 1990s. By this time, Akoni-Pule Highway connected Kawaihae Harbor to North Kohala and passed directly in front of Kailapa. DHHL had high hopes for Kailapa’s future. Its 1992 annual report boasted “the department’s 10,000 acres at Kawaihae have the potential to become a major commercial, industrial, residential, shopping, recreation area.” DHHL commissioned a 10-year master plan and environmental impact statement complete with maps, architectural renderings, and plant species lists. As far as fresh water, the report simply mentioned that “this development plan will require new water sources.”

There is a luxury development at the northern boundary of Kailapa called Kohala Ranch. The developer drilled wells in Kohala Ranch in 1979, 1982, 1989, and 1993. Luck struck twice when those last two drills hit freshwater 136 feet and 18 feet above mean sea level. It appears that ancient geology underneath the area traps fresh water before it reaches the island’s sea-level basal lens, where it would more typically sit atop saltwater that has intruded underground. The perched water was tapped, filtered, and distributed throughout the gated community.

Following Kohala Ranch’s lead, DHHL drilled two test wells on their property in 1990 and 1992. Dr. Jonathan Likelike Scheur, an experienced water policy consultant for DHHL, explained how DHHL was not so lucky: “The same water consultant who told Kohala Ranch where to drill their wells told us where to drill our wells. Kohala Ranch’s wells are potable with sweet water and our wells are salty.” According to a DHHL-commissioned Kawaihae Water Assessment study in 2015, one of the wells “could never produce quality potable water” while the other well was drinkable, but just barely so. In order for DHHL to feel confident about distributing the water to beneficiaries, the study recommended “additional desalination treatment.”

the high cost of water

Without high-quality water of its own, DHHL dramatically scaled back its 10-year master plan. It eliminated plans for schools, shopping complex, hiking trails, and golf course. It installed roads and power lines to service 195 empty residential lots. Then it struck an agreement with Kohala Ranch Water Company to purchase water and pipe it about two and a half miles laterally across the landscape. Beneficiaries moved in and largely built homes with their own hands. Today, about 192 ʻohana and almost 600 residents call Kailapa home. Still reliant on the private water system, these Kailapa residents pay “some of the highest water costs of any customers in the State,” according to HHC Chairman Kali Watson in his September 2023 testimony to the U.S. Senate Committee on Indian Affairs.

The reason water costs so much is because water is heavy. Moving water from its source and pumping it to consumers takes a lot of energy. Hawaiʻi claimed the title for the highest average residential retail price of energy in the United States in 2023 at 41.74 cents per kilowatt hour. The further water is pumped away from its source, the more it costs.

The County of Hawaiʻi Department of Water Supply has 23 water systems on the island of Hawaiʻi. Systems where water is minimally moved cost less to operate. On the Hilo side of the island, heavy rainfall, shallow wells, surface springs, and diverted rivers mean water does not have to be pumped relatively far. On the Kona side of the island, however, much of the water is sourced from deep wells and must first be pumped against gravity to ground level before it is additionally pumped and distributed. The county is able to spread operating costs for all 23 systems across its entire customer base. Dr. Scheur explains that “the policy of the County Board of Water Supply is to charge a single rate across the island which, as an environmental justice issue, means that poor people in Hilo are subsidizing wealthy people in Kona.” It is not perfect, but it is the department’s form of equity.

Donna Parker uses a hose to water the lawn outside her property.

The consumers of Kohala Ranch water are not so lucky. “The Kohala Ranch system as a standalone system has no cheaper water sources that are balancing it out,” says Scheur. In 2023, all 506 customers of Kohala Ranch Water Company are sharing the high cost of pumping water, including DHHL. From 1998 to 2018, DHHL attempted to create its own form of equity for its beneficiaries through fiscal policy action; it paid Kohala Ranch Water Company the full amount for water and then charged Kailapa residents the more realistic rates set by the County of Hawaiʻi Department of Water Supply. DHHL covered the difference in cost to the tune of hundreds of thousands of dollars a year. In 2018, however, DHHL decided it could no longer afford this massive shortfall.

The policy decision that the commission faced was: Do we spend $1 to help our existing lessees with their water bills, or do we spend that same dollar to help those on the waitlist? explained Andrew Choy, DHHL program planning manager. “At that time, the choice that the commission made was to try to utilize more of the trust resources to help those on the waitlist.” DHHL redistributed the money they were saving every year by no longer subsidizing Kailapa residents — $165,783 in 2016 — toward programs designed to shrink the infamous waitlist.

This decision to prioritize a backlogged waitlist over offsetting Kailapa’s expensive water is the manifestation of DHHL’s scarcity mindset. A scarcity mindset presumes more for others means less for some. With the mindset of abundance, DHHL could both take care of current beneficiaries and move potential beneficiaries onto homestead land. But abundance is not a word used often in the department. DHHL has a history of receiving meager funding, and Choy is frustrated. “Instead of trying to generate revenue off trust lands to help with the department’s mission,” he says, “getting consistent and sufficient funding from the legislature would help make those choices easier for the department.”

Choy is referring to the historic practice of DHHL transferring land to non-beneficiaries for commercial use to generate operating revenue for the department. Although the department is required by law to be adequately funded by the state, this has never happened. Since 1959, the State of Hawaiʻi has thwarted the success of DHHL by providing a fluctuating amount of inadequate funding each year, or in some years, no budget at all. On top of that, the state has fought DHHL in court, fought beneficiaries in court, and neglected to act on recommendations set forth in federal audits such as developing a comprehensive Home Lands infrastructure development plan and providing a target date for proposing legislation to sufficiently fund the Home Lands program. The 1992 audit found 7 unresolved recommendations and only 1 implemented. Kailapa resident Donna Parker sums her feelings up clearly: “I feel like nobody gives a rip. They really don’t.”

In the Kailapa subdivision, water rates are over six times Hawai‘i county’s rates and slated to increase by 400 percent before 2030.

waiwai for some

Donna Parker lives on a ridge in Kailapa with an impressive view. From her lānai, the cobalt horizon meets the rugged Kona-Kohala coastline and stretches up to the three massive mauna in the interior of the island. In the near distance, an out-of-place patchwork of vibrant green hugs what would naturally be arid kahakai leeward land. The lush landscaping of Mauna Kea Beach Hotel, the Westin Hapuna, and their associated collection of luxury resort homes is fed by water from the county water system. Unsurprisingly, this oasis comes with an “extremely high average water use,” according to the 2010 Hawaiʻi County Water Use and Development Plan, which “can likely be attributed to the large water users in the Mauna Kea Resort.”

As the resort delivers a carefully crafted and heavily irrigated version of Hawaiʻi, just down the road, Parker’s lawn tenuously hangs onto life. Parker loves her plants and still waters what she can, despite her high cost of water. At 83 years old, she has learned how to keep a positive attitude, despite the daily visual reminder of resource inequity. “I look out there at all the stuff down by the ocean, meaning all your hotels and all those God-blessed high makamaka homes, and then I look at my mauna,” she says, “and I look at the sky and look at the beautiful ocean and then think, ʻI’m blessed.’ If I don’t do that, I think I might go nuts. I don’t want to be grouchy all the time about stuff that doesn’t happen here.”

Sadly, history is repeating itself. In 1957, 100 Hawaiian Homes beneficiaries were unable to move onto unoccupied homestead land in Waimānalo. The Honolulu board of supervisors claimed there was not enough water for the development in its Suburban Water System while simultaneously providing water for an adjacent subdivision and approving the construction of a new one down the road. The newspaper Honolulu Record reported that “many are asking why … Harold Castle’s Kaneohe Ranch is getting ample water for its subdivisions and is planning more subdivisions with hundreds of homes.”

From the ʻio’s eye view, Kailapa is meant to accelerate Kānaka economic self-sufficiency through the provision of land. But self-sufficiency will never be achieved when beneficiaries are being gouged with every turn of the faucet. DHHL is aware that the water crisis is negatively impacting its mission fulfillment. In 2014, DHHL published its Water Policy Plan with the vision of “adequate amounts of water and supporting infrastructure” across all homesteads so beneficiaries may return to ‘āina with the “self-sufficiency and self-determination” that HHCA intends. The water policy plan is well worded, but like President Eisenhower said: “Plans are worthless, but planning is everything.”

Kailapa resident Diane Maka‘ala Kaneali‘i on the Lānai of her homestead in Kawaihae, Hawai‘i Island.

an intact ahupua‘a

In the early 1990s, a few homesteaders founded the Kailapa Community Association to begin planning the new community’s identity and direction. It became a nonprofit in 2010, and Kailapa resident Diane Makaʻala Kanealiʻi led its volunteer board of directors through the process of seeking grant awards to fund community visioning sessions. The sessions aimed to answer the question of how to thrive, not just survive, in Kalaniana‘ole’s vision of self-sufficiency.

What resulted was the 2019 Kailapa Community Resilience Plan titled “Ehuehu i Ka Pono – Thrive in Balance,” a co-created and tirelessly researched proposal for turning the ahupuaʻa into ʻāina momona. Speaking from her living room, Kanealiʻi remembers the excitement surrounding the visioning process.

“We had around 20 UH students that came to Kailapa, and they brought all of our community into my home. It was so windy that we couldn’t go outside, so we were packed like rats in here!” she says. “People showed up! A lot of our neighbors, especially the ones who have been here for a while. They wanted to see something happen.”

University of Hawaiʻi law students at Ka Huli Ao Center for Excellence in Native Hawaiian Law led the creation of what has become a roadmap for economic self-sufficiency, community cohesiveness focused on human interaction, and the resourceful management of water and land. Kawaihae I is one of only two ahupuaʻa solely owned by DHHL. If this resilience plan were actualized, Kailapa would be a prototype of indigenous wisdom flourishing in a modern world. Kailapa would be a functioning 21st century ahupuaʻa, from the summit of Kohala to the sea.

A zoning map in “Ehuehu i ka Pono” reimagines all 10,153 acres of the DHHL Kawaihae land. The land is divided into traditional wao, or, biological resource zones, as well as more modern campuses. Kahiko and ʻauana ideas are blended seamlessly. Beans and grains grow along with kalo, and ʻuala, demonstrating how Hawaiian lifeways are not a romanticized past but a living continuum. There are pastoral parcels, solar farms, restored forests, hiking trails, salt pans, and fishing grounds. According to the report, “The goal is to reconnect the ahupuaʻa system, restoring forests where there were forests, replanting agriculture where there had been agriculture, and building a thriving community.”

This report is more place-based than DHHL’s 10-year plan for Kailapa from the early ’90s that never came to fruition. Unlike DHHL’s version, there are no golf courses or water-guzzling plants. But just like DHHL’s 1992 plan, nothing can happen without water.

the passing of the torch

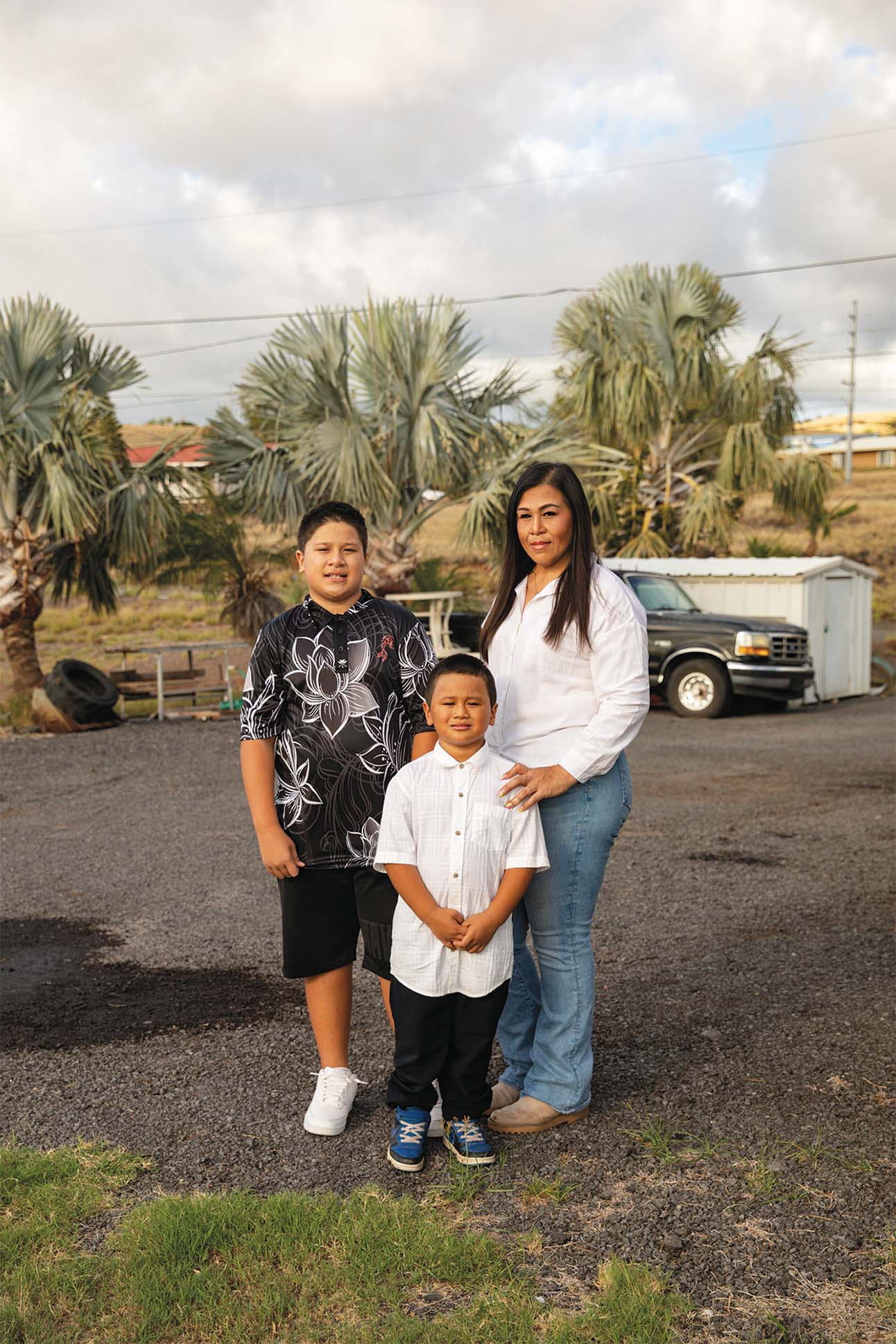

Shawna Kaulukukui is raising her two sons in the house her father built in Kailapa. Only the two-laned Akoni-Pule highway separates her corner lot from the crashing waves.

“My dad built this house 15 years ago, and we would come here on the weekends,” she says. “This was like our getaway from home when we were younger.”

Kaulukukui grew up in Hilo and moved to Honolulu to pursue her career. After she had her first keiki, the busy urban Honolulu lifestyle had her reflecting on memories of a life more fully connected to her community, the sea, and her father. “My dad loved it over here. He loved the fishing, the weather, the people,” she recalled. She returned to Kailapa in 2014 to raise her two sons the way she was raised, in a caring community and easygoing environment.

In 2022, Kaulukukui became president of the Kailapa Community Association. She gives her time, just like board presidents before her, to the pursuit of grant funding for community projects and initiatives. Just as it has always been, water is a top priority for the board. The year Kaulukukui took over, DHHL awarded the Kailapa Community Association a grant for $49,375 that the previous board sought for “research and feasibility to use a DHHL well and desalination treatment facility.” The board contracted Edward Halealoha Ayau of Halealoha Consulting Inc to execute the project, with the goal of showing DHHL that using an existing well with an additional water treatment facility is a feasible option. The grant delivery date is July 31, 2026. Kaulukukui and the board are trying to move things forward to meet that deadline.

It would seem that Kaulukukui and the rest of the association could benefit from paid support. But there is just one grant specialist in all of DHHL, and unfortunately, this person was on medical leave for most of 2023. Underfunded and understaffed, DHHL continues to struggle to make good on the promise of the HHCA. Putting the burden of planning on beneficiaries — many of whom work full time like Kaulukukui — means projects move along painfully slowly, or, as is the case of finding a new water source for the people of Kailapa, not at all.

Resident Shawna Kaulukukui became president of the Kailapa Community Association in 2022. She wants to raise her two sons in the house her father built in Kailapa.

finding water in a desert

Kailapa community sits in a true desert. By nature, water will always be scarce in this community by the sea. The county water system may be capable of transmitting water to Kailapa like it does the Mauna Kea Resort, but the system truncates a mile short of Kailapa. The County of Hawaiʻi Department of Water Supply is clear about the fact that extending the water system is neither its top priority nor, ultimately, its responsibility. DWS Manager-Chief Engineer Keith Okamoto told attendees at a July 2023 Waimea town hall meeting: “We are looking at other ways to extend our system along state highways across the bridge from Kawaihae side, but that is going to take a long time and is going to cost a lot of money. … We don’t have the funding resources to do what really, maybe, Hawaiian Homes really needs to take care of.”

That same 2015 water assessment study from DHHL confirms Okamoto’s fears. Extending the county water system across Honokoa Gulch would cost $18.5 million to $28.1 million. Even if DHHL could find the money, it would have to find a whole new source of water since, according to the study, “there is no available water source that is not already allocated to development.” Allocated to development, just not Kailapa’s development.

The sting of this statement is painful given the topography of the area. The fully allocated Waimea water originates from stream diversions in the “wet mountain regions of the Kohala Mountain forest reserve,” according to the 2010 Hawaiʻi County Water Use and Development Plan. This is the same forest reserve that abuts the mauka boundary of the DHHL Kawaihae property. The redirected Waimea water goes on a 12-mile, circuitous journey down the mountain, east and west through Waimea, down Kawaihae hill, and laterally across the coast where it finally stops short of Kailapa. The water is pumped 12 miles every day, while Kailapa sits seven miles below the source.

reverse osmosis

Extending county water to Kailapa will not happen anytime soon, and piping water seven miles downhill from the intermittent Kahua ditch is too unreliable. The last option, which is desalination of its well water, is the most feasible solution. A prototype functions only five miles from the neighborhood.

In 2019, tech entrepreneur and former Reddit CEO Yishan Wong was looking to retire in Hawaiʻi when he drove past Kailapa on Akoni-Pule Highway. A few miles down the road, Wong stopped when he saw a for-sale sign. The 50-acre parcel had no power grid to connect to, but the property did come with a brackish water well and plenty of year-round sunshine. Years prior, Wong may have continued down the highway without a thought of purchasing the property, but a monumental shift had just taken place. Since 2019, the least expensive way to build a new energy grid has been with renewables — that year a new solar facility became 177 percent cheaper than a new power facility run on coal. With this data, Wong understood he could develop a 100 percent clean energy grid at an exceptionally reasonable cost. What he did not understand was that he could live out DHHL’s dream for Kānaka. He could build a kauhale for his ʻohana and raise his kids next to the ocean in Hawaiʻi.

Inside the Kaulukukui’s kitchen.

Today, Wong has a reverse-osmosis water treatment facility run entirely on solar power on a property five miles away from Kailapa. With it, roughly 25,000 gallons of brackish water are pumped from the well, forced through membranes in a process called “reverse-osmosis,” and turned into fresh water that not only flows from the tap but also irrigates the native dry forest garden on the property. Because of the photovoltaics, this process also happens without burning any fossil fuel.

While Kohala Ranch Water Company pumps water using electricity that is the most expensive in the country and passes the cost burden onto DHHL consumers, Wong shows us that, perhaps, another way is possible. Cleaner photovoltaic energy can power pumps to desalinate and distribute water at cheaper rates. The question then becomes, who is responsible for seeing these solutions through to completion? If we look at history, the state seems to believe the kuleana falls on DHHL.

As a luxury resort delivers a carefully crafted and heavily irrigated version of Hawaiʻi, just down the road, a resident’s lawn tenuously hangs onto life.

But, stretched thin and underfunded, DHHL has put the onus on its beneficiaries. The beneficiaries try their best to thrive in a messy situation inherited from the intentionally impaired HHCA. Since the overthrow of the Hawaiian kingdom, Kānaka Maoli have been tenacious in fighting for the bare minimum — the right to speak Hawaiian in public school, the end to military bombing of Kahoʻolawe, no jet fuel in drinking water. But it is time the state gives Hawaiians more than the bare minimum, and Kailapa could be a perfect opportunity. Kānaka deserve to run their own experiments with a significant amount of land.

After all, so much land in Hawai‘i has been lent to experiments. We know what happened when we experimented with planting thirsty sugarcane across Kohala and watered the fields via concrete stream diversion ditches; the sugar industry boomed then vanished, leaving fallow fields to catch fire in high winds on a heating planet. We know what happens when we experiment with allowing cattle to run across the forested slopes of volcanoes; watersheds shrink underhoof, taking harmonious native ecosystems with them. Native plants and native bodies are one in the same; Kānaka ancestors, family members, and kino lau are replaced by fire-prone monotypic stands of imported grasses. We know what happens when we experiment with allowing hotels and resorts to indiscriminately irrigate landscaping and golf courses dotted along the desert coastline; limited water is not allocated to infrastructure for more local housing solutions, leaving families across the island to subsidize the aesthetic appreciation of thousands of jet-lagged malihini.

We also know what happened when a group of the greatest sailors ever known launched from the shores of Tahiti 1,000 years ago in boats carved from trees and lashed together with plant fiber. They navigated to a group of islands, bountiful with nonhuman communities, and learned how to live in ecological interdependence. The sailors fed hundreds of thousands of people for hundreds of years, retaining about 85 percent of the native forest cover while no money exchanged hands. This proven ʻāina use-case scenario is called the ahupuaʻa.

DHHL has only two intact ahupuaʻa in the catalog of land tossed its way in a legislated act of codified racism and corporate greed. One of these ahupuaʻa is Kawaihae I. Descendants of these magnificent sailors and land managers are asking to experiment with stewarding this ahupuaʻa in order to find out if socio-ecological harmony can happen once again. It’s unclear if this type of stewardship has been attempted at this scale in the last 250 years. We do not know what will happen. We do know what can happen if we don’t allow it. We have allowed others to use this land. We have seen the results. It is time the State of Hawaiʻi and the United States of America give the Kānaka ʻŌiwi of Kailapa the resources they are asking for so they may caretake their own land in their own way. Imagine what can happen. Ua mau ke ea o ka ‘āina i ka pono.