Drawing from Native Hawaiians’ climbing heritage, Kānaka Climbers is reenvisioning what ethical outdoor recreation looks like in Hawaiʻi.

Images by Elyse Butler

Deep in the Waipiʻo lowlands, on the island of O‘ahu, the Kānaka Climbers met under a rising sun. Contrary to their name, this was no ordinary climbing excursion. Instead of chalk bags and climbing shoes, a dozen climbers were armed with trash bags and safety gloves, and rather than scrutinizing rock faces for handholds and routes, all eyes were trained on the trail underfoot.

“We don’t do much climbing at our events,” said Skye Kolealani Razon-Olds, executive director and co-founder of Kānaka Climbers, as she led the crew in a clean-up. These bimonthly trips are more educational than recreational, meant to enlighten climbers with the overlooked histories of the sites they frequent.

The group packed into truck beds, carpooling up the road to stop at an easy-to-miss trailhead that led down to Kīpapa Gulch. Leggy trees cast shadows overhead as the occasional off-distance hum of a dirt bike dragged by. They paused at a boulder where Razon-Olds and her family pointed out a few climbing routes before proceeding deeper into the gulch.

“We’re going to go way past the climbing area. We’re going to go to all the significant sites, really going to make sure that there’s a deeper understanding of the space,” said Razon-Olds, who reminded the team not to rush through the clean-up even as the trail proved laden with bouldering opportunities. They’re encouraged to return later, once they have learned more about the site.

In 2017, a since-wiped video circulated on social media within the local climbing community of climbers scaling across markings that resembled petroglyphs along a popular Nuʻuanu route. Upon seeing that clip, Razon-Olds studied the area and confirmed that these were kiʻi pōhaku, or petroglyphs, and they were sprinkled throughout the site. “There was a misunderstanding of how significant the site was,” she said, prompting her to found Kānaka Climbers in the incident’s aftermath. Some carvings were so faint they could easily go unnoticed, a problem at such a high traffic route where regular human interaction can quickly erode the historical markings.

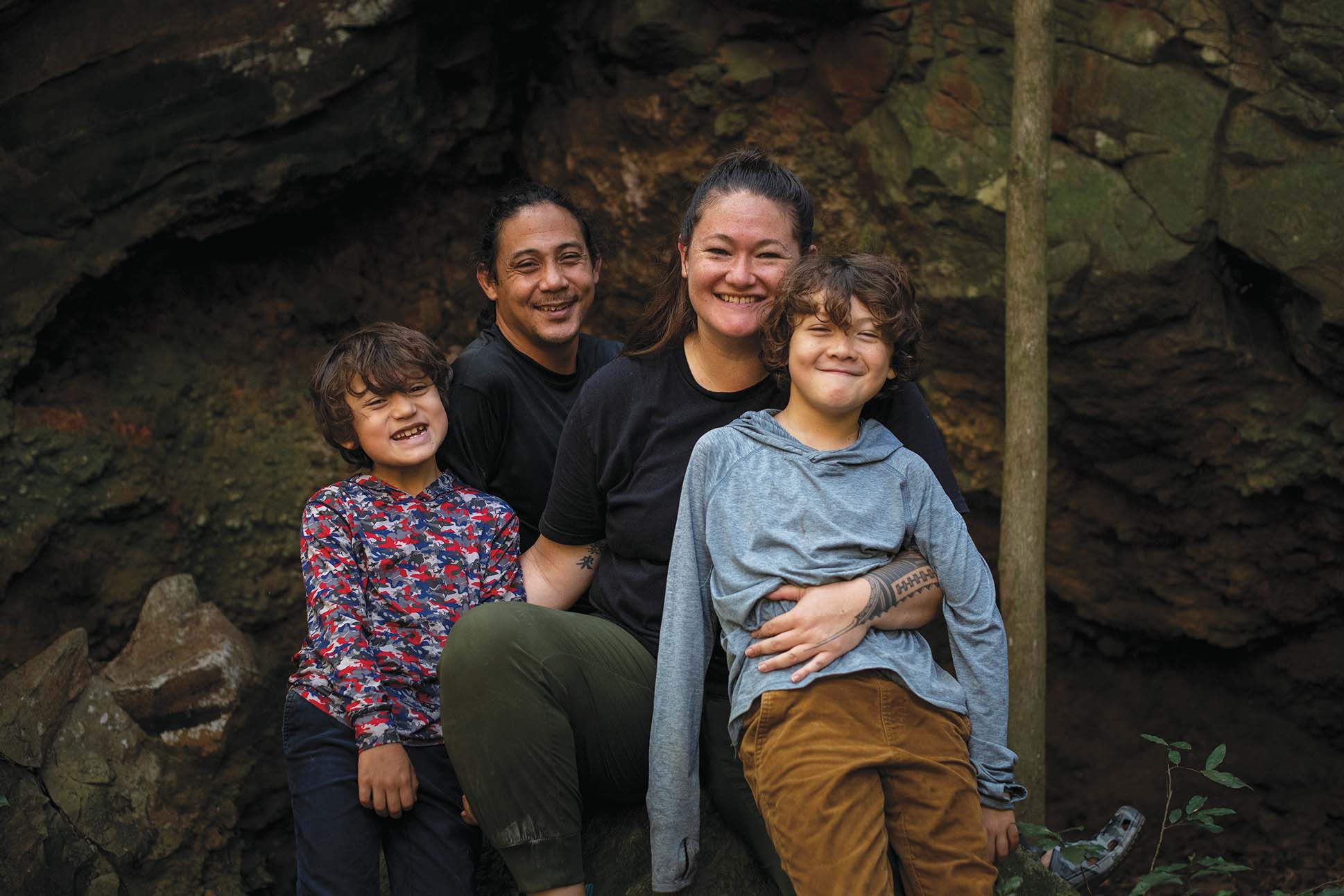

Skye Kolealani Razon-Olds is the executive director and co-founder of Kānaka Climbers. The preservation of ki‘i pōhaku is among the group’s main objectives. Their ethos teaches that pōhaku, or rocks, are not meant to be conquered while climbing.

The lack of signage and resources is an issue seen across the islands, exacerbated by the lack of cultural education around outdoor sites. “The majority of cultural sites on the continental U.S. actually have signage. That is something Hawaiʻi has not jumped on board to,” she said. Contrast that with the past, said Razon-Olds, when Hawaiians protected sacred sites and kept them within their family’s kuleana, their responsibility.

Razon-Olds in particular grew up scaling rock walls and boulders to burial sites of her ‘ohana, a practice she continues today with her children. Some were positioned in caves of varying elevations with handholds carved out for climbing accessibility. There she learned how to safeguard iwi kūpuna, or ancestral remains, removing invasive species or clearing up sites after rockslides. Through Kānaka Climbers, Razon-Olds uses the lessons learned from these traditional practices to better inform her fellow recreationalists.

“Climbing was innately Hawaiian and Indigenous,” she said, more so used “to complete a practice, to either get to a fishing site, a hunting site, a secluded place where people were living to make sure other valleys couldn’t get to them, or it would be for burial practices.”

Following the U.S. overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom in 1893, land rights and development severed families from sites that ʻohana once stewarded. Kānaka Climbers’ efforts are meant to preserve the remaining sacred spaces frequented by hikers and climbers with the hope that state and local governance will eventually implement appropriate management such as signage, paved trails, and enforced access to properly protect these spaces.

The trail that runs through Kīpapa Gulch once connected the lowlands of Puʻuloa, or Pearl Harbor, to Līhuʻe, or Schofield. The areas in and around the stream are steeped in history. Its name translates to “placed prone,” a fourteenth-century reference to the slain warriors that paved its terrain, and recalls two notable battles fought along its banks. The now dried stream snakes through traditionally stacked rock wall terraces once used for dryland gardening, vestiges of a once thriving lāhui (nation). Scattered across its fields are rock faces carved with kiʻi pōhaku dating back to the 1400s and are one of the highest concentrations of petroglyphs on Oʻahu.

In 2023, Koa Ridge, a residential development parallel to Kīpapa Gulch, planned to build deeper into the Waipiʻo lowlands, an expansion that would have demolished nearby rock walls laden with kiʻi pōhaku. In an effort to preserve the sites, Kānaka Climbers members and archaeologists reported their findings proving the area’s cultural and historical significance in a board meeting to the State Historic Preservation Division, ensuring that the developer won’t be able to bypass cultural protection laws.

Climbing was innately Hawaiian and Indigenous.

Skye Kolealani Razon-Olds

The group’s ethos teaches that the islands’ rocks and cliff faces are not meant to be conquered while climbing. They instead help recreationists to cultivate a deeper relationship with the sites.

“I get it, I don’t own a home and I understand the larger aspect of housing our people,” says Razon-Olds. “For me, being able to partake in these larger development plans is important as a community member who wants to one day own a home but also make sure we maintain what makes Hawaiʻi, Hawaiʻi.”

At the end of the trail, Razon-Olds led the group up an unmarked path. Carved on a rock face was an assemblage of kiʻi pōhaku. Participants were encouraged to look closer, but not to touch. They were advised to report other petroglyphs they may find throughout the day.

The surveying, reporting, and preservation of kiʻi pōhaku are among the group’s main objectives. With a team of volunteer archaeologists and cultural advisors, the organization ensures that there is no risk of damage to a culturally significant site before inviting participants.

The group’s ethos teaches that pōhaku, or rocks, are not meant to be conquered while climbing. Instead, recreationists should seek to cultivate a deeper relationship with these sites, respecting them as spaces with storied significance, and in ensuring the environment’s health, these sites can continue to be used both traditionally and recreationally.

Upon arriving at so-called ʻŌpala Falls, nicknamed for its popularity as an illegal dumping site where trash gets chucked over the edge of the highway and runs down a steep rock wall into a pool of litter that pollutes the gulch down below, the group got to work clearing out the stream. They would end up collecting two truckloads of trash. But before the excursion’s end, two of the group’s keiki announced a discovery.

“We found more petroglyphs!” they shouted, pointing up a rock wall at least two stories high. There, kiʻi pōhaku were just visible underneath a thick layer of moss. It was of at least one figure, perhaps depicting familial relationships similar to the surrounding petroglyphs. The mountain face’s tricky topography alludes to the skill with which the carver had to climb.

A couple of climbers trekked up the hillside to get a closer look. They jotted down their observations; further proof that these sites, more than mere playgrounds, conceal centuries of stories yet to be told. “If people aren’t aware of the cultural properties that are here, there aren’t going to be people that fight for it,” Razon-Olds said. “That cultural education makes all the difference to making sure that we have space to protect it.”