From Tehran to Los Angeles and then Honolulu, the artist and writer Navid Sinaki discusses self-discovery, alternate archives, bridging aches, and the craft of a clever storyteller.

In the realm where thoughts fleet, gardens stand eternal. A universal soil we can hold in our hands, as material as the passing rain. Within the pulsing sun lies a series of miracles revealing itself to you. All of them say something similar, yet distinctive. What imbues this environment of lush subtlety? The fusion of the perpetually aged with the freshly imagined? We share a parallel technological bedrock where new seeds are constantly sown in the past’s underground, the surface green with potential. Where creation exists in continuous self-discovery, we polish our jewels and let them glitter in the sun’s rays. What unfurls when all your cherished ephemera and memories converge at once? Private blog entries, lovers, and magic emerge.

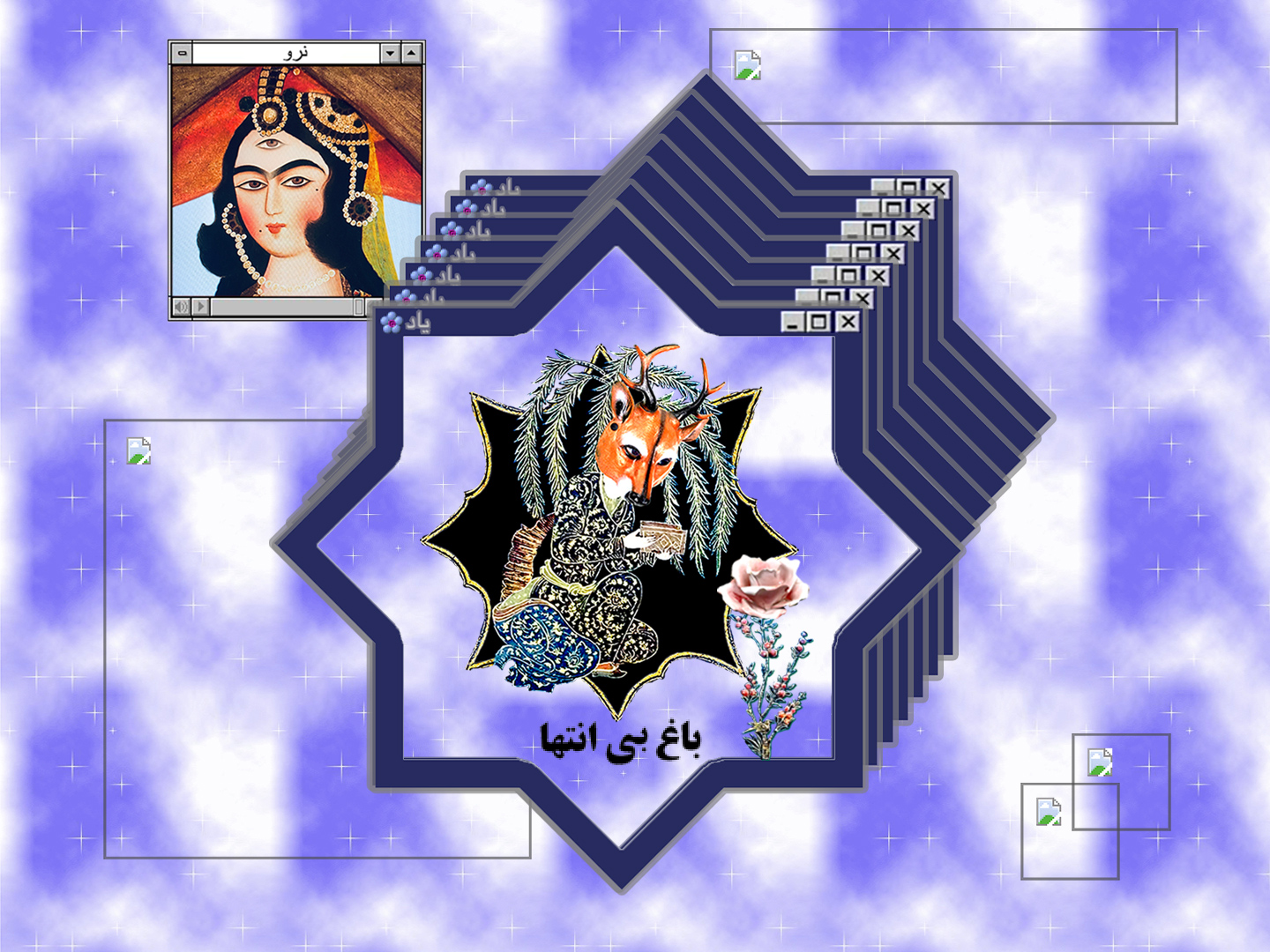

Navid Sinaki’s visual storytelling beckons like a dream in progress, adorned with glitter, Easter eggs, secret sounds, and unlocked doors. It grows and regrows, abundant and charming, intertwining and superimposing the playful and unexpected upon what is familiar: a chatbox is a manuscript, a statue is a story, a person is a place. Some thoughts shrink while some catch on like a pop song you haven’t heard in 200 years.

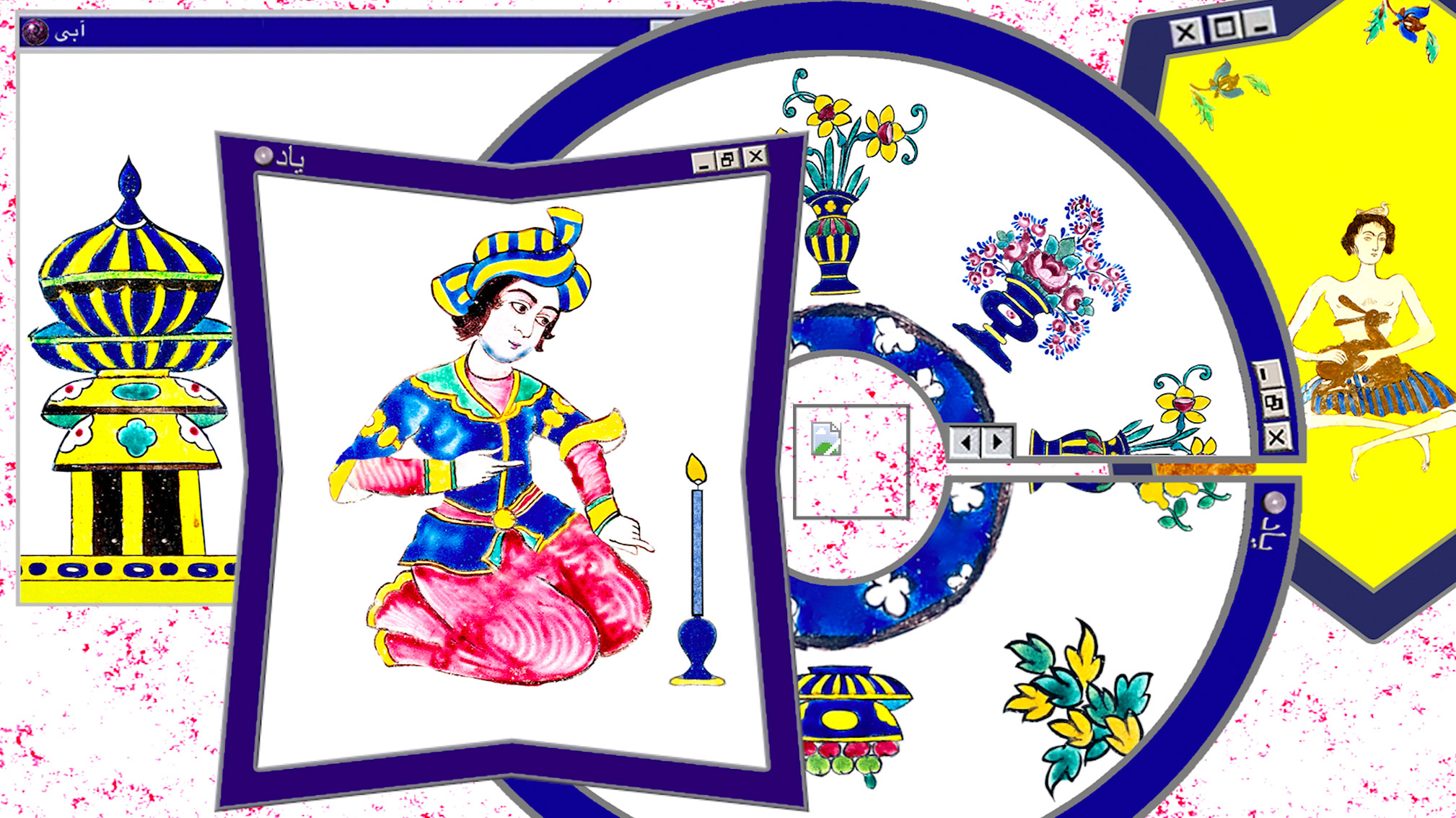

Sinaki’s first solo exhibition, The Infinite Garden, is a queer reimagining and epic tale of the artist’s own making, exploring themes of love, desire, and storytelling roused by a fascination with the early internet, ’90s pop culture, and his Iranian heritage. A result of Sinaki’s time in Honolulu as an artist in residence at the Shangri La Museum of Islamic Art, Culture and Design in 2023, the short films and faux ephemera in The Infinite Garden, on view at Shangri La and Honolulu Museum of Art through June 23, connects both venues through Persian paintings from the Zand and Qajar periods, tilework, and manuscripts pulled from Doris Duke’s home collection.

To furnish The Infinite Garden, Sinaki appoints digitized manuscripts, early internet visuals, GIFs, and VHS cassette packaging. His multiplicitous assembly extends the limits of curation into a procreative place challenging one’s context within history, promoting self-discovery. From these seeds, a space is summoned for queerness within Persian mythology, where one may engage with history, technology, context, and personal identity altogether at once.

Meet me at the intersection of modern-age digital storytelling and ancient-born personal mythologizing.

Hi, Navid! Can you introduce yourself?

My name is Navid Sinaki and I’m an artist and an author. I was born in Iran, but my parents left Tehran during the Iran-Iraq War when warfare increased in intensity. I grew up in a Southern California suburb, so my childhood was a mix of ’90s pop culture and the slices of ephemera from Iran. The only cultural spot in Rancho Cucamonga was the local Barnes and Noble. I also found a home in the channel Turner Classic Movies, where I watch many old films. I had a simultaneous love of text, imagery, and film that blossomed side by side.

How was your time as an artist in residence at Shangri La? How did that come about?

My residency at Shangri La was the most magical and cherished experience in my artistic career thus far. Curator Kristin Remington had come across my work through the American Muslim Futures exhibit from 2021. For that online exhibition, I showcased some early work that deconstructed old Persian painted manuscripts and reimagined them with Y2K-era gifs. Kristin and I had a particular kinship over early website design and esoteric memes. Kristin asked me if I was interested in a digital residency at Shangri La. With it came keys to the kingdom: a site visit, during which I was able to peruse the staggering collection of art and artifacts that Doris Duke surrounded herself with.

I had a magical amount of access in a way no other cultural space would allot a fledgling artist: trips to the archives to handle delicate books and manuscript pages, and ample time exploring the tile work that makes the museum a unique paradise. There were no limits or parameters, no censorship or limitations. I was allowed to produce a body of work of my own desire.

I was so moved by my experience at Shangri La for many reasons. I knew I wouldn’t be returning to Iran any time soon, since my work is queer AF and homosexuality is criminalized there. But through Doris Duke’s former home, I was able to explore art and artifacts I’d never be able to see because of my indefinite estrangement from my birthplace. There is a sense of longing with knowing I won’t go back, but I was suburbanized early on. My identity was something other than purely Iranian or purely American. Self-exploration was the name of the game, I just needed to create the rules.

Iran wasn’t the site I wanted to explore. A person can be a place. I wanted to document how I felt, my version of my identity without heavy value judgments of good, bad, better, authentic, or imposter.

There was no cohesion to my early work that mashed up Persian miniatures and the early internet. I just enjoyed the thrill of emptying old artifacts of human figures, and adding early aughts gifs to them. I felt like the early internet was its own manuscript, programmed not painted. Also, I had been told by a relative that Islamic art was iconoclastic (anti-figural representation), but quickly learned this was a fallacy. Rather, some of the work (depending on intent and location) was aniconic. Visual depictions varied depending on space and context. Why not turn a painted landscape into a beaded wonderland? Why not erase and insert? I wanted to find a space for my queerness and also for my imagination.

I am inspired by your re-telling of Persian epic tales. Activating charged, meditative spaces to witness queer stories reveal themselves, framed by a type of digital that is considered outdated. How do ancient spaces and objects hold immediate stories?

I’ve only recently come to terms with my diasporic identity. I used to feel a sternness to “carrying the torch of culture,” which was counterproductive. Just because I didn’t speak Farsi fluently and my squiggly Persian handwriting is at an elementary level didn’t mean that I couldn’t explore my own relationship with my culture. Instead of feeling a weight of obligation, I decided to lean into the weightlessness of play. What did I have at stake? I always live heavily in my daydreams, sometimes in a world parallel to reality. Because I’ve written stories consistently since elementary school, the act of looking has always been an act of insertion: given a set amount of objects, what is the story one can create? This helps me be a good liar (in concept, not execution). What is a storyteller but a really clever liar?

Even though I didn’t speak Farsi language confidently, I read many Persian texts (translated), poems, literature, and epics. The umbrella structure of these works always appealed to me. Meet the storyteller. Hear the rules of the game. Proceed to hear a variety of stories. It is a similar strategy to the Arabian Nights. We hear of a cruel king. We meet the storyteller Scheherazade. We learn the rules of the game: she will tell a story nightly to delay the king’s thirst for bloodshed, a cliffhanger each night.

In Nizami’s Haft Peykar (The Seven Pavilions), a king builds seven domes or pavilions for his seven lovers. Each corresponds to a different country and color. The king dons the color of the dome before visiting each lover, so she can tell him a moralistic tale. I decided to invent a story along those lines called The Infinite Garden. My umbrella story was this: A king builds a garden for each of his lovers, one of flowers, another of fruit, and a third garden full of potions. Each day, the king visits one of his lovers, who regales him with a story.

My first creative breakthrough — the first artwork I made that received public attention in screenings, museums, and inclusion in a book on queer cinema — was a film made while I was a student at UC Berkeley. I was shocked when I discovered Persian melodramas sexploitation films from the ’60s and ’70s. I only knew of the Persian New Wave that existed post-Islamic Revolution, stark films about sick cows, poor farmers, and ailing children searching for shoes. Powerful films, but not ones that carried the frivolity I liked so much about Classic Hollywood films. The popular films of the ’60s and ’70s (known as “filmfarsi”) reminded me of 1930s Pre-Code films from the US. They were sexy, they were sordid, and they were fun. I re-edited several films starring Iranian pop icon Googoosh to make the film Pop! The end result was a trans-romp set in the cabarets of Tehran. I painted over the scenes (literally on my laptop screen) and created my own world within a world.

I’d like to talk about The Infinite Garden more. Curated by you, this narrative serves as an umbrella of epics and stories of your creation. The tricks, the sounds, the phantasmagoric quality of the projections and sound beside hard sculpture. Can you speak more about this and its activation? What pulls you towards and into the digital to recite these particular tales?

Shangri La was very gracious about letting me exhibit my work alongside the artifacts that inspired me. I was intent on showing work that had been safely archived, but unseen by public eyes. I immediately knew I wanted to create a reason for the immense Qajar painted women to be exhibited. My sneaky plan was to include them in videos so it made sense to have them on display.

The Infinite Garden is a blessing and a curse. Because I’ve immersed myself in so much early internet ephemera, I started to think about what an alternate archive would look like. Ever the storyteller, I knew just showing images of early websites didn’t have the sense of play I wanted to relay. A larger umbrella story would add a different kind of heft to the body of work, and would allow me to make a throughline from my ’90s childhood ephemera, and the cultural play that brought ease to inner identity crises.

I had my interests: early internet, VHSes, Persian myth, queerness, and storytelling. Thankfully, I found an object I knew could be a central force. The fireplace in the Playhouse [a guest suite located in a separate structure] at Shangri La had so many figures I knew I could isolate and animate. From there, I created a king and three lovers, each with an identifiable garden and storytelling structure. Because the fireplace is installed in a location that is rarely open to the public (in a gorgeous museum that already requires some effort to visit), I wanted to create access to it by presenting it through my work.

Why not turn a painted landscape into a beaded wonderland? Why not erase and insert? I wanted to find a space for my queerness and also for my imagination.

Navid Sinaki

Much like I was inspired by a mix of paintings, tilework, and metal objects, I wanted to make a variety of work. Specifically, short films, vertically aligned single-channel looped videos (to mimic a manuscript page), VHS cases (an alternate version of a manuscript page), and a slideshow of partially fabricated website pages. They were all connected as ephemera related to this non-existent epic about a king and his three lovers. So, iterations of The Infinite Garden are just as infinite. I liked the idea of people learning about an epic based on the work it has inspired, rather than by a fully complete, real text. It’s all several steps removed. The slideshow portion allowed me to slow the process of animation down to the utter stillness of one slide at a time, sometimes two views of the same page (“scrolled down”), and sometimes just a GIF reduced to separate slides, such as an hourglass whose rotation is painfully and pleasurably slowed down.

In short, I saw art and artifacts that inspired me. I wanted to exhibit as much of it as I could. I also wanted to strengthen my own work by contextualizing it as an alternate archive, alongside revered “serious” historical objects. Also, I wondered, “How could internet culture get the museum attention it deserved?” The objects from Shangri La’s archive, and the images from the early internet, needed to be given the honor of contemplation. A museum at its best allows both context and contemplation.

I love the visual aesthetics that you play within. What were your favorite websites as a child?

AOL defined what I thought was the internet. My dad never came to Iran with the rest of the family because of his former employment as an engineer during the Shah’s reign. Instead, the rest of us would visit and would come home to a fridge full of sodas (a sort of “welcome back”). One time, we came home to a computer. It was the first family computer. Fairly soon, we popped in one of those AOL trial CD-ROMs that was regularly mailed out (“127 Hours Free!”).

Back then, I wasn’t aware of websites. For AOL, you just typed in a keyword “MTV” or “Nickelodeon” and it took you to a “page” owned by that entity. I didn’t learn about the “www” of it all until much later. My favorite keyword was “CLUELESS” because it took me to a page based on the movie. I printed out the official lingo dictionary from the film so I could study “Bettys” and “Barneys.” Eventually, Geocities became my favorite site because it allowed me to create my own web pages. I had at least three, each with a persona of its own. My most prized one was called The Enchanted Forest. I don’t remember what was on it, perhaps a few vignettes I wrote, a moody rose GIF, and a Britney Spears banner. I also loved finding Angelfire pages about witchcraft. Oh, the spells I tried.

I’ve only recently come to terms with my diasporic identity. I used to feel a sternness to ‘carrying the torch of culture,’ which was counterproductive. Instead of feeling a weight of obligation, I decided to lean into the weightlessness of play.

Navid Sinaki

What does internet purity mean to you?

Internet purity is a complicated concept. So much hinges on the word “purity,” and I never want to sound facetious about the early internet elements I collect, composite, or re-imagine. There is a “purity” in knowing the impermanence of these collections. I made a few e-diaries in my pre-teen and teendom, and for me there was this beautifully private space where I could create a world of my own. That worldbuilding was quite simple: a font, a page name, a few graphics, and a custom visitor counter at the bottom. That was all it took to feel a sense of public privacy. It feels innocent in retrospect for a number of reasons. For one, the idea of making the private public was far more humble. Meaning, a fan blog about the show Felicity wasn’t tied to the website creator as directly as content is now. Finstas aside, content production can be incredibly identity-based. “Look at what I made, buy the supplements I take, believe the joy from this documented trip #ad.” But a fan blog was just a fan blog. A MIDI choice on a website just meant you liked that song. But these early website pages were also monetized. For example, there were Amazon.com headers that gave the website owner a few fraction of cents if anyone redirected to Amazon from their page.

More than anything, depictions of grief were so earnest in early internet websites, it feels brutal. For my process, I click through the Internet Archive to fill thematic folders I keep on my desktop: clouds, fairies, blue, glitter, memory are a few folder names. Every so often, I come across a website that is a tribute to someone’s death. The text is as heartbreaking as the imagery. Sometimes they are decorated with photos of the deceased. Sometimes they are customized composites: a baby photo in a pixelated “snow globe” with birth and death dates digitally engraved. Spelling errors are common on most old website personal pages I peruse. There’s this quick energy of “I love this, I feel this, I want to document this” that is captured.

I would call my perusal a version of internet purity. I go into the search not knowing what I will find or come across. There are broken links and corrupted image files during my digital tourism. What follows is a glimpse of someone else’s immediacy, now partially documented in a way that likely wasn’t imagined: incomplete but still emotionally impactful. Searching the word “heart” can lead to many early GIFs that sparkle and float. Or something unexpected might pop up: a 9/11 eagle in a heart charm GIF, or another dead baby in a heart frame with Winnie the Pooh in the corner. My reaction is pure — bruise for bruise, I feel a morsel of what someone else might have felt. Through my work, I hope to bridge the ache.