For more than three decades, photographer Ed Greevy documented land struggles and political strife in the Hawaiian Islands. Here, a look back on how those movements formed and resisted, as he observed from behind the camera.

Ed Greevy’s first camera lens—a 500-millimeter Telefoto—was an extravagant purchase for 1962. An aspiring surf photographer, Greevy reasoned he needed the heavy-duty piece of equipment to zoom in on Oʻahu’s powerful breaking waves from the shore. He aimed to produce images that made it seem as if the viewer was right there in the barrel.

It is this creative impulse to reach the center of a subject that would drive and inform Greevy’s photographic career in the decades that followed. The images for which he became most known have little to do with surfers or surfing, yet they zeroed in on a sea of change, swelling around Hawaiʻi’s rising social consciousness.

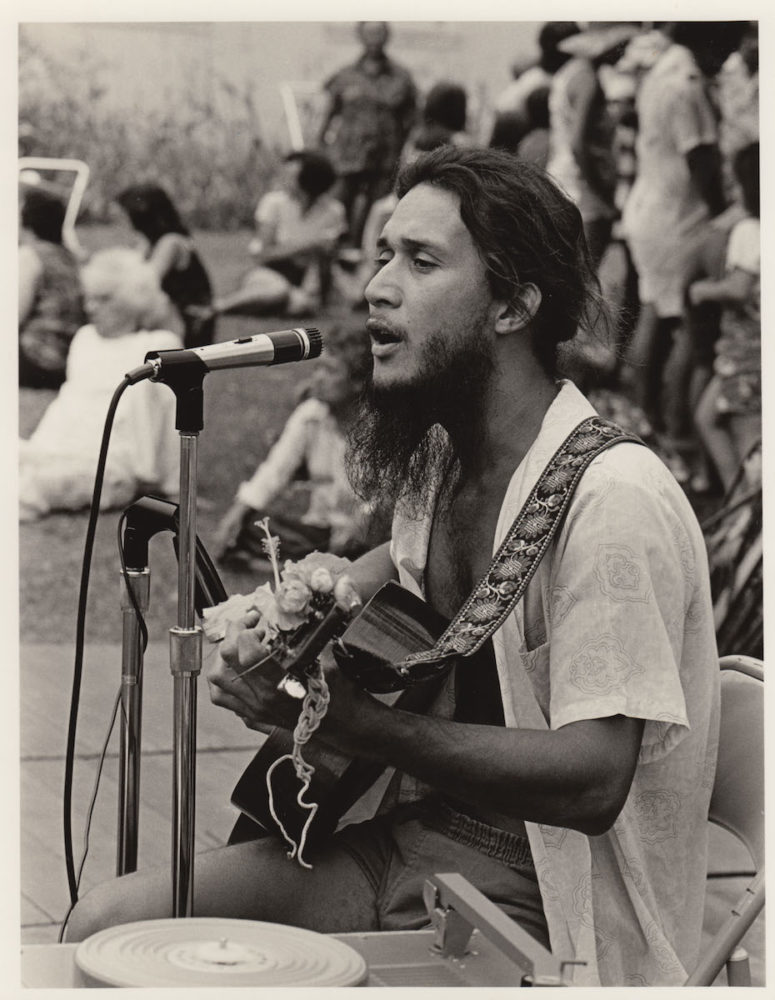

His coverage of protests, speeches, and civil disobedience in the ’70s, ’80s, and ’90s over the development of Hawai‘i’s beaches, the displacement of local communities, and desecration of Hawaiian culture would achieve the visual depth he searched for in those waves.

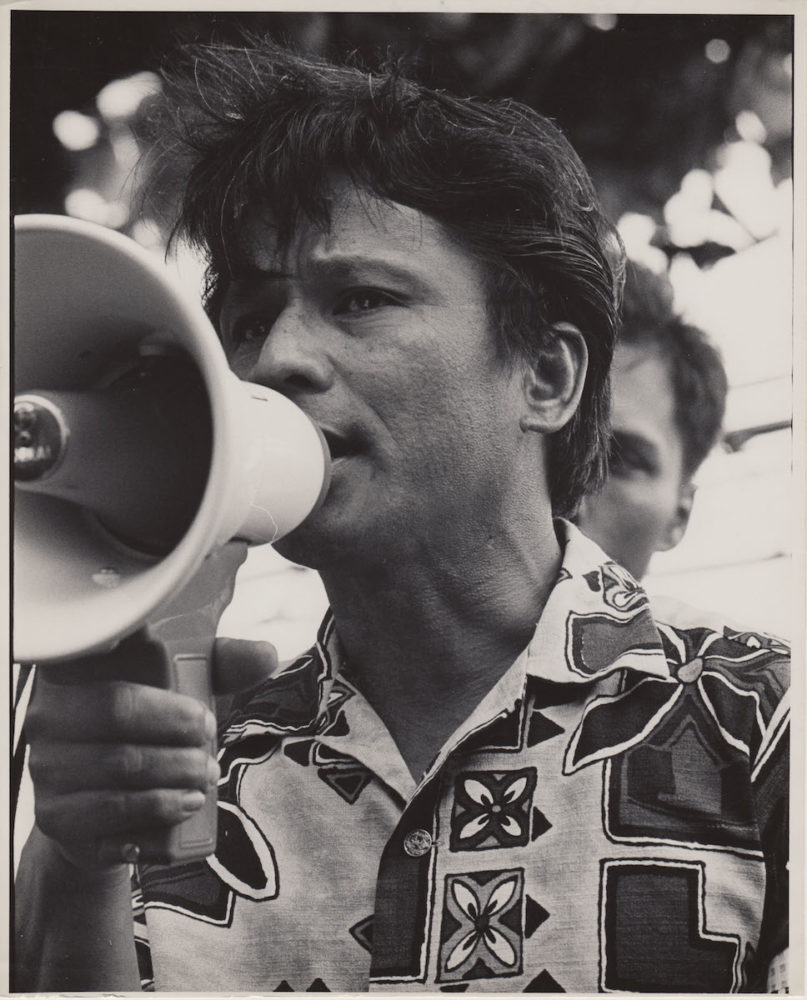

A tight frame could be dedicated to a person rallying at a podium or a wide shot of a crowd so overwhelming it was rendered a single solid shape. The effect of these visual rhythms transports the viewer into the same psychological sphere: You feel in the middle of something big. Instead of shooting power from a distance, he shot it up close among the people and the crowds—and he would never need that Telefoto lens to do it.

Definition of a Good Photo

On a summer morning at Ed Greevy’s apartment in Makiki, sunlight streams through a window and glints off his spectacles. He has a thought.

“The definition of a good photo is something that impacts you emotionally,” the 79-year-old says, “and imparts a lot of information.”

His living room is packed with black-and-white prints he has taken over the years—some are scattered across a coffee table, while others hang on the walls, covering nearly every inch. Like a roll of negatives in a canister, the room feels like a tightly filled space in which time stands still.

“In a complicated photograph, the subject needs to be very clear,” Greevy says.

Set flush in a corner of the room is an industrial metal cabinet. It stands more than six feet high and has two gray doors. He swings them open to reveal neatly stacked black trays. The cabinet is largely organized by location, and on the side of each tray, bold, Sharpie-scrawled words announce their contents: “Kalama Valley,” “Chinatown,” “Mokauea Island,” “H-3,” “Makua,” and so forth—his filing system marching through Hawaiʻi’s notorious history of razing the natural landscape and evicting people from their residences. Inside there are, he estimates, 60,000 prints and negatives.

The definition of a good photo is something that impacts you emotionally and imparts a lot of information.

Many people already know a Greevy photo without even knowing they do. Think of activist Haunani-Kay Trask, her fist thrusting forth from a gazebo at ʻIolani Palace, following a march in 1993 on the 100th anniversary of the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawai‘i.

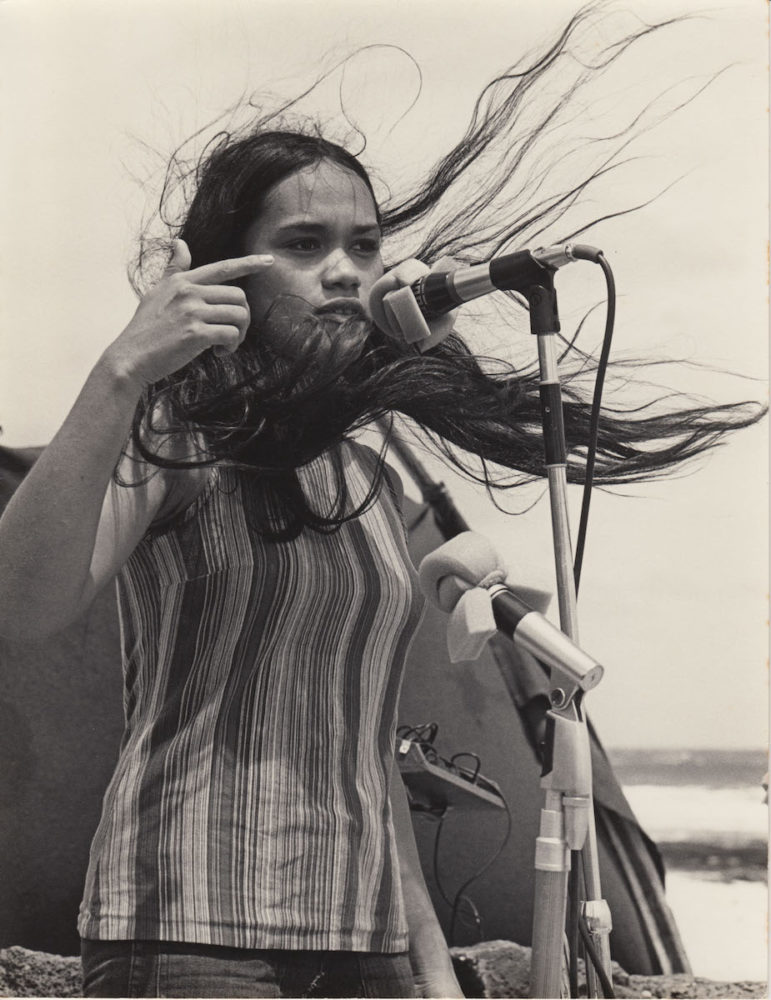

Or recall Terrilee Keko‘olani, a young adult defending Sandy Beach in 1972 against city plans to build a 5,000-unit housing development across the shoreline, the wind blowing dark locks of hair across her face as she speaks into a microphone. In another well-known visual, a Hawaiian man in a gourd helmet, his arms crossed defiantly, protests the military bombing of Kahoʻolawe at the Hawai‘i State Capitol in 1977, a motion blur keeping only his eyes and head in tight focus. Everything else in the frame is shaken and disoriented, as if the world is exploding around him.

Photo Collections

Today viewers are able to consider Greevy’s tremendous output collectively, most readily in Kūʻē: Thirty Years of Land Struggles in Hawaiʻi, a hardcover photo essay book published in 2004. While many photographs rely on captions to provide context, Greevy’s are illuminated through his concentration on signage: “People Not Profits,” “No Bulldoze,” “Housing is a Right,” and “Decolonize.”

They both show and tell us their battles and the climate of the times. This printed retrospective, however, casts his photographs in a different light than that of the more practical and urgent purpose for which they were intended.

Greevy’s earliest images were developed exclusively for leaflets and notices to be handed out by community organizers. The images were a conscious currency used to rouse public support for the groups and nonprofits—Save Our Surf, Protect Kahoʻolawe ʻOhana, Kōkua Hawaiʻi, Ka Lāhui Hawaiʻi—that began to energize the local landscape.

More often than not, this collateral would circulate without his photo credit. “And that was fine,” Greevy insists. “It was never about me.” A self-proclaimed leftist, Greevy’s intention was to help sharpen the struggles and political efforts of these groups. “I’m not a photojournalist, I’m not neutral, and I don’t pretend to be,” he says. “I always support the underdog, and the photos are my way to do that.”

Born in 1939 in Los Angeles, Greevy first visited Honolulu in 1960 as “an adventurer,” he describes himself then, with a group of friends. The plan was to attend the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa for a semester, but he fell hard for surfing and dropped out after two weeks. “If I could spend eight hours a day in the water, then that was a good day,” he remembers.

He spent the following spring and summer chasing waves, and then returned to California to finish a degree in political science at Long Beach State University. In the years that followed, he picked up his first camera, a 35-millimeter Nikon F, and began a career in insurance that took him to New York City. Greevy eventually made a move back to Oʻahu in 1967, immersing himself in commercial photography including travel advertisements and promotional material for musicians. He also set up his own film lab on Cummins Street.

“Besides the newspapers,” Greevy says, “I probably had one of the biggest darkrooms on the island.”

The first protest Greevy photographed was on March 31, 1971. It was a mass demonstration at the Hawaiʻi State Capitol where two community groups, Save Our Surf and Kōkua Hawaiʻi, joined forces to raise concerns over a number of burning issues, including the planned widening of Kūhiō Beach and the evictions of residents living in Kalama Valley.

Electric Times

“It was electric,” Greevy says, of the estimated 2,500 people who turned out. The Capitol, which had only been built a few years prior, had not experienced a focused rally of that size before. “The legislators closed and locked their doors,” he says. Greevy was swept up in the impassioned tempo of the crowd comprised mainly of young adults in their late teens and early twenties. But it was John Kelly, the 52-year-old founder of Save Our Surf, moving back and forth from speaking at the podium to the fringes of the crowd, who captured Greevy’s fascination because he noticed Kelly using his own camera to document the event. Inspired to help, Greevy offered up his own Nikon, so Kelly could stay immersed in the action. “The photos were my way to contribute,” Greevy says. He left with eight rolls of film and a lifelong friendship.

Kelly understood how to use photography to seize public attention. At his home at Black Point, Kelly had a printing press that he used to materialize Save Our Surf’s political ephemera. “John always said the only free press is your own,” Greevy says. Because Kelly’s tactics relied on dynamic photos, he began to call Greevy when he needed someone to chronicle the group’s activities.

With Greevy’s images, Kelly could streamline and customize Save Our Surf’s communications to get the word out. Greevy became more invested and involved. “John never went anywhere by himself,” Greevy says. “He never went to argue with a state official on his own. He always brought people with him. Because he always wanted to demonstrate power. That’s what the politicians listened to.”

If I was going to support someone, I was going to make them look good. Heroic, even.

The intense proximity between the camera and the subject has always been a source of drama and satisfaction in a Greevy photograph. In a memorable image of resisters forming a human barricade to block police officers from entering a Chinatown building to evict residents, Greevy is close enough to the action to lock arms with them. During an anti-racism rally led by Hawaiian Studies students at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, his camera is so deep in the fold that the final images are swallowed by signage. Because of Greevy’s comfort in navigating these contentious spaces, it’s impossible to ignore the resisters’ message.

When first visiting a community, Greevy “never went in cold,” he explains. “I always went with someone respected or known [by the community]. Often that was John.” Alliances between groups were major sources of amplifying their messages and actions.

Following statehood, Hawaiʻi underwent a considerable period of urbanization as its economy began to shift from agriculture to tourism. Eventually, Kelly began to bring Greevy to document the struggles of affiliates of Save Our Surf such as Kōkua Hawaiʻi, which was fighting against evictions at Kalama Valley, Chinatown, and Waiāhole-Waikāne.

Landowners were terminating short-term leases of residents who had lived in neighborhoods for generations in order to pave the way for hotels and more commercial businesses. “From there, relationships develop, people remember you,” Greevy says, “and welcome you the next time you come in alone.”

Facing the Familiar

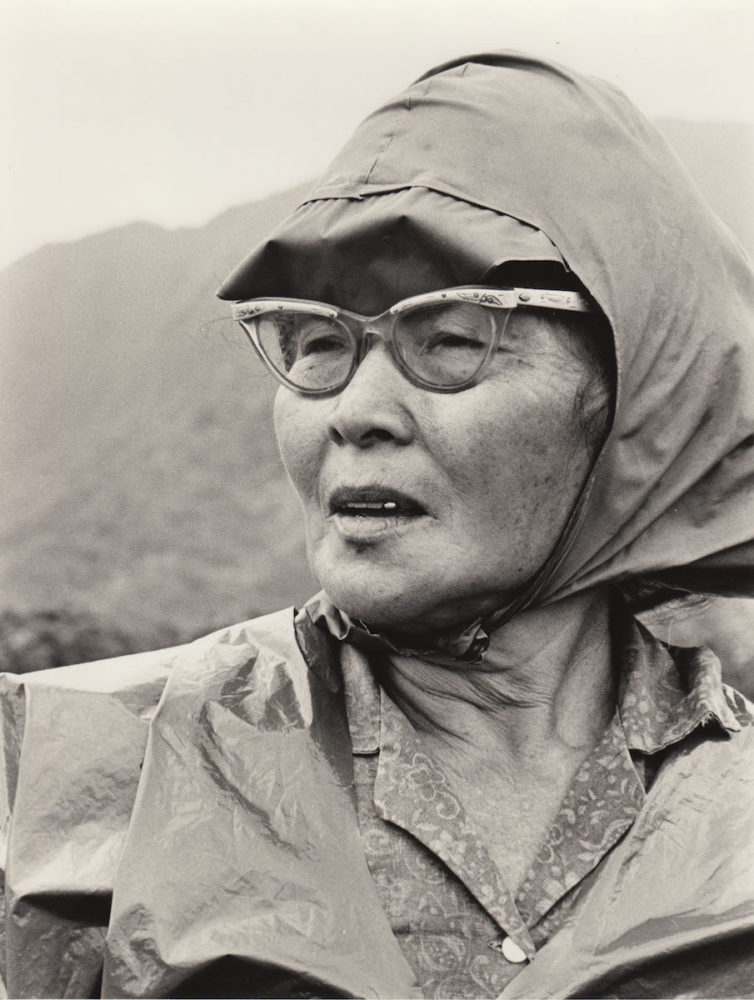

There’s a sense of familiarity with the communities and organizers in Greevy’s photography that is most arrestingly on view in his portraiture. The intimacy asks a compelling question: How did this Caucasian man from Los Angeles gain the trust of so many groups wary of outsiders?

Greevy recalls management training he attended in the mid-1960s in New York City. It was a session on how to work a room, assert one’s influence quickly. “They were all the rage then,” he says, smirking. He realized that most of it didn’t translate in Hawaiʻi.

As Kelly began to introduce him to more communities, Greevy grew sympathetic to their struggles. While attending their town halls and group meetings, he made a conscious effort not to be seen as the “pushy haole,” he says. “Don’t feel like you have to intervene. Just shut up and listen.” Greevy’s ear was most sensitive to when people were talking among themselves. In the conversations he overheard, he was able to better understand how people felt about an issue and connect with them.

This patient approach to his subjects is what makes the portraits so emotionally generous. While they are primarily absent of the cues that conventionally represent power, such as crowds and onlookers, Greevy’s images of individuals command respect nonetheless.

His close-ups aligned impassioned citizens with well-known leaders. “I would shoot at a low angle to make the everyday person look more powerful,” Greevy says.

“If I was going to support someone, I was going to make them look good. Heroic, even.”

Greevy’s biggest influence was the American photojournalist W. Eugene Smith, who was known for black-and-white compositions and an evocative emphasis on contrast. But there are shades in Greevy’s work reminiscent of other photographers, namely Gordon Parks and James Barker, both of whom documented race relations in the United States during the Civil Rights era.

As in Parks’ photos, there are the rallies and the signs, but there are also homes and children. The visual grammar of Greevy’s images has similar parallels—they speak in shouts, but also in whispers.

“A lot of the people I was shooting were from marginalized communities and hadn’t had photos taken of them before. They hadn’t ever seen themselves,” Greevy says. “I wanted to help them see themselves.”

Kaua’i

There’s a tray in Greevy’s cabinet labeled “Kauaʻi” that’s a poignant example of this. In 1974, he visited the Nāwiliwili-Niumalu area to meet with organizer Stanford Achi, who was uniting the community in resistance to urbanization along the southeast coast of the island. Hotels were scouting the beaches and backyards for future developments.

Greevy, as expected, tirelessly photographed the meetings, the speeches, and the sign waving; his posed portraits of the group affirmed their human army. After this is where most photojournalists would exit the scene. But Greevy lingered to show their way of life: landscapes of men and women tilling taro fields, young girls in muʻumuʻu laughing while they walk their bikes home, paddlers in canoes in the Hulēʻia River, the water glistening and the river beds untouched. When Greevy clicked away at a subject, he was aware that something was always at stake.

I just hope my photos inspire people and remind them of their power.

Greevy, who is retired and doesn’t shoot as much these days, is content with the legacy his photographs leave behind. He’s been researching archives to someday house this library of images.

“I just hope my photos inspire people and remind them of their power,” he says, as he locks up the cabinet that holds his life’s work. “That’s their only value.”