An illuminating conversation with Michelle Mishina on discovering photography, fostering connection, and finding the narrative.

It may sound trite, but Hawaiʻi photographer Michelle Mishina knew it was time to return home through social media. Mishina had been living in Los Angeles for over a decade, its urban sprawl flush with creative energy in everything from fashion and food to art to music. The scene was inspiring but overwhelming at times too. There was always so much to see and do. One day, while scrolling on Instagram, a short video popped up on Mishina’s feed. It was a little clip of wind moving through grass in Kohala on Hawaiʻi Island. “It was a video of nothing really,” Mishina. Its power lay in its peaceful simplicity: “It just called me home.”

I first Mishina in 2018 on a work assignment. We met on Hawaiʻi Island where she had grown up. There is a certain pleasure in seeing someone move within the space that had shaped them. That space lights up their senses. In watching Mishina move gracefully through her surroundings to snap photos, I enjoy her curious delight in finding unexpected angles or unusual textures. She pauses, raises and lowers her camera, then smiles a quiet smile as if discovering a secret. Through the shutter, Mishina is afforded a glimpse of Life’s fleeting beauty. And then, she graciously shares it.

Rae Sojot At what point did you pick up a camera?

Michelle Mishina My dad loved taking pictures of our family. He’d have little disposable cameras scattered all over the place and would take pictures of us doing whatever random thing we were doing. He wasn’t a photographer by any means, he just liked documenting our family. I probably picked up a camera because he had them laying around. We lived in a neighborhood that was near a cliff and every day I’d walk my dog Toby down to an empty lot that overlooked Kealakekua Bay. I’d bring one of the disposable cameras with a flash and I would take a picture of the sunset– you definitely don’t need a flash when you’re taking pictures of the sunset. (Laughs) Every now and then I would capture something that made me really excited about the photo, though I didn’t know what it was. That’s when I started regularly taking pictures, but they were literally just sunset pictures with no context, nothing. Just sky.

RS When did you graduate beyond the disposable camera?

MM Once my parents saw me taking all these pictures with the disposable cameras, they got me an SLR camera for Christmas.

I eventually brought it to college, using it for snapshots of friends or if I was on a little trip, I’d take pictures in the same way that we use a cell phone camera today. During my last year in college, I took a photography class. I’d look at the photos of my friends and think, “Well, these are actually kind of interesting.” They didn’t feel as much like snapshots anymore. It wasn’t a conscious decision to learn photography, I just started to make my photos with a little more intention and care.

RS When did you think your photography could be a career?

MM I had been taking pictures as a hobby – I’d meet up with friends for little photo walks. I remember thinking, “Okay, I have a camera. Let’s see what I can make with it.” When I got the photos back from the lab, I thought, “Oh, this is kind of unexpected and interesting.” Eventually I decided that the worst day taking photos would probably be better than the best day in an office, so that’s when I decided to pursue photography full-time.

RS Did that strike something in you?

MM I was excited that I could frame the world in a way that I didn’t initially see, like, I could shift my perspective and find a way to look at it differently. So, I began to play with composition and arrange things in my frame. I think composition came pretty naturally to me.

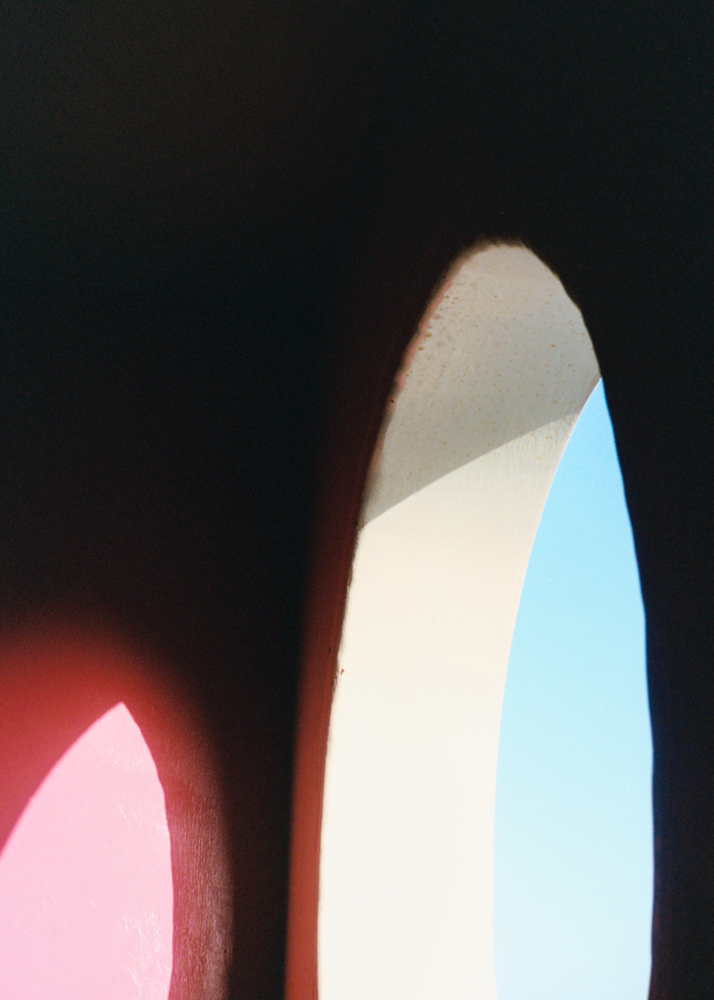

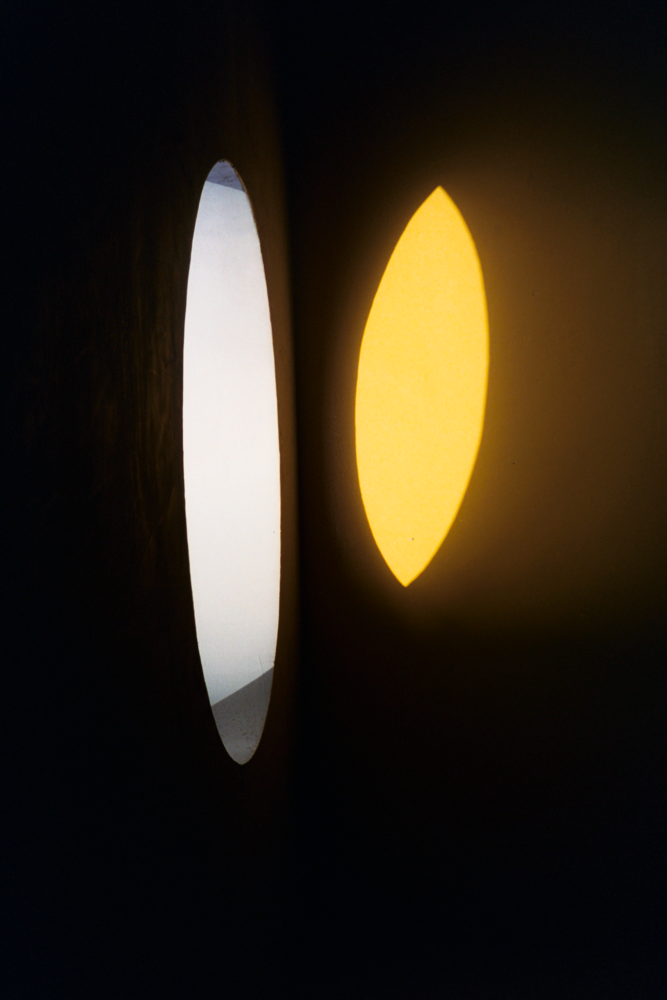

RS There have been lots of occasions where we’ll be walking together and you’ll stop because you like how light interplays. What is it about light?

MM Light’s always changing. Until I went to ArtCenter College of Design, I hadn’t really considered light as an element of pictures. I just thought about color and composition. During my first term at school, I had a class with a teacher, Ken Merfeld who was a bit grouchy and intimidating. When I walked into his class on the first day, it was dark. We had to find our seats in the dark. Once everyone arrived, he closed the door, and it became pitch black. We sat there in silence for maybe five minutes? It felt like 10 hours. Nobody said anything. And then Merfeld asked, “So, what is photography?” A couple of brave people were like, “Well, it’s a subject,” “It’s a color,” “It’s composition.” But Merfeld didn’t say anything. We were confused– what was photography? Then we heard him move a little bit. He struck a match. Suddenly you could see the shape of the room from the glow of that match. He said something along the lines of, “Without light, there is no photography. What are you recording? It’s nothing. You need light to take a picture.” We had to shoot a roll of slide film each week and project it on the wall. And every class he’d say, “None of you have found light yet. I don’t see any light. My mother could take this picture. Why did you take this picture?” It was months until someone took a photo and he said, “There it is. This person found some light.”

RS What did that photo look like?

MM It was a picture of an iron rail with a decorative ball on its end. You could see a highlight on the sphere. And all of us were like, “Oh, so that’s what light looks like.” (Laughs) We couldn’t see it before. Ever since then, I try to notice where the light is. The particularly beautiful thing with light is that it comes and goes so quickly, it’s never the same twice. Knowing that is a good way to be present in your environment and pay attention.

I love that about photography: you start describing it and you feel like you are also describing life.

Michelle Mishina

RS Can you give me examples? Because I’ve seen you stop in all different environments — urban, natural. What catches your eye?

MM Maybe the color or the quality of it. Is it hard? Soft? Dappled? Is it the main light source or reflected? We could be walking through a city and if there is bright light, the quality is different whether it’s the sun directly versus if it’s the sun reflecting off the building. Different kinds of light can evoke different feelings. If you’re in a hospital waiting room with fluorescent lights overhead, you’re going to feel one thing. But what about the golden light of the afternoon shooting through some leaves overhead? That’s going to be a different feeling. Light is changing constantly. I like to see what it’s doing.

RS (Laughs) Yeah, I’ve noticed. I can probably think of a handful of times that we’ve been walking around, and you’ll stop in a parking structure, and you’ll point out an exchange of light and shadow that I would not have even noted.

MM That’s a big part of it. You can’t just have light, you have to have shadows too, otherwise there’s no definition to that light. They influence each other, light and shadow. I love that about photography: you start describing it and you feel like you are also describing life.

RS Let’s pivot for a minute. You and I have a shared love for sensory experiences. We both love perfume. I remember you turning me on to Sophie Calle, the artist behind the Chromatic Diet who would compose items of one color into a visual monochromatic feast. What is your relationship with senses? You like perfume, you like light…

MM I like food. (Laughs.) I also love music. I like the idea of luxuriating in my senses. I love when you can be overcome with the beauty of an incredible meal, or you can lose yourself in music. Our senses are a way of both grounding us, planting us firmly in the here and now, but can also be a means of escape. If you sit quietly and listen to all the sounds around you, or you feel the breeze on your skin, if you smell a particular aroma, these are transient, temporary things and noticing them is a way of being present. But music, food, smells, they can also transport you. They feel so linked to memories and dreams.

RS Let’s pretend your photography is a perfume. What would your photography base notes be?

MM Like perfume, a good photograph has layers, some of which aren’t apparent immediately and only reveal themselves with time. Maybe you first notice the color or composition of an image, or the light. Then the second read is what’s actually happening in the frame. And the third read is what’s happening in the foreground or background, or maybe the social or political context. And with each layer that unfolds before you, your interpretation of the image changes.

RS I remember that story you told me about a woman who wanted portraits done. I remember it being a little sad because she had such high hopes and then you could almost feel her anguish upon seeing how she looked in the photos.

MM I typically work with “regular” people. They’re not models or celebrities who are used to seeing themselves and presenting a certain face to the world. And oftentimes when people see themselves in photos, they’re judgmental of their image because they know all their flaws and insecurities, and they focus on those things in the image right away. But we’ve all had those photos from 20 years ago, where we’re like, “Oh my god, I look so good.” It’s such a common thing—to not realize how beautiful you are until too much time has passed.

RS In those particular instances, how do you help navigate subjects through that?

MM I don’t do anything overtly. I have to trust that eventually they’ll see the beauty that I see in them. When I show up for a portrait with someone, I know my job is to take a picture, but my real goal is really to see who they are. I’m curious about them. The camera becomes this sort of intermediary that allows me into their space, like a passport. You can create beauty through curiosity.

RS Are some borders closed?

MM Yes, and can you tell right away if they’re not comfortable with letting that attention come. And then there are people that have a specific look or pose that they like to do and will not stray from it, no matter how much you try to guide them. When I look at someone that I’m photographing, I’m curious about them. I see them as beautiful, and I know they have a story to tell. It’s like, “Let me know you!” (Laughs.)

RS For me, as a writer, I agonize over the cadence and flow of passages, where each word is like a note. What’s most agonizing for you as a photographer?

MM The editing. When I’m taking the picture, I’m trying not to miss anything, so I shoot a lot of photos. As I’m trying to take it all in, I’m also thinking, “What is the story here? What’s the framing?” I don’t know what I’m going to feel attached to later when I look back on the experience. Editing is where the story comes out. Say we spent the day together and I photographed whatever you did. I could portray you a million different ways based on the kinds of photos I selected for the final edit. The editing process is a chance to revisit the experience and ultimately determine the story by choosing the images that best support it. That’s very hard for me to do.

RS What do you mean?

MM I can’t remember who first said this, but there are always three people in any portrait: there’s the subject, there’s the photographer, and then there’s the viewer of the photo too. Each person has their own idea of what’s happening. They’re interpreting it in their own way. The photograph is essentially a documentation of that relationship, and evolves or changes based on the viewer. Choosing the image or a sequence of images influences how the viewer perceives the story, which may or may not be different from how the subject or photographer experienced it.

RS When you look back at your work from a decade ago, what are some of your initial reactions to your previous work?

MM I wasn’t physically close enough, and the photos are either too literal or too interpretive. I think they lacked a sense of emotional and stylistic balance. I’m honestly not sure I’ve found that balance yet. I think I was afraid to be in people’s space and was a little more distant in how I photographed. Once I got comfortable being with people and asking to be in their space, that allowed for an intimacy between us. People opened up more. Sometimes they’ll share their story with me, and we’ll talk about it, or I’ll just listen. Sometimes I don’t even take the picture until much later. I’ve photographed people where at the end we have to hug because we went through an emotional experience together. Sometimes photography is less about taking photos as it is about having an experience with the subject. The camera allows me to be in these places that I wouldn’t normally be and talk to people who normally wouldn’t talk to me. That’s the most exciting thing about photography.

RS Is there any style that you really admire?

MM I admire people whose styles and processes are very different from mine. There’s a photographer, Frank Ockenfels, who does a lot of portraits of celebrities and musicians. His subjects have been photographed over and over again and yet, somehow, he still gets totally different images of them. That inspires me. It’s a different way of seeing, right? His photos are not technically perfect. They could be seen as messy or incorrect because they’re out of focus or blurry or scratched. But they give you a feeling. I think that’s what’s important—not to capture what things look like, but what they feel like. Maybe that’s why I like light.

See more of Michelle Mishina’s photography at her website.