The young designer is skirting the boundaries of aloha wear with his buzzy, eponymous fashion label.

Images by Nani Welch Keliʻihoʻomalu and Courtesy of Michael Vossen and Rocket Ahuna

For four months, last winter, a small Waikīkī hotel room functioned as the designer Rocket Ahuna’s makeshift atelier. On the fifth-floor of Kaimana Beach Hotel, tables and a sewing machine had taken a couch’s place and the detritus of a nascent fashion house in production littered the space. “Sorry, it’s such a mess in here,” said Ahuna, stepping around scraps of aloha print fabric and poster boards with Polaroids of local models.

Ahuna’s lithe six-foot frame was styled in thrifted jorts and a blue palaka top of his own creation, feminized with coquette flairs of a Peter Pan collar and subdued puff sleeves. Under an aloha print bucket hat tumbled a mass of long wavy hair that he deftly ties into a low bun in moments of concentration. His ensemble telegraphed a keen understanding of trends and how to make them his own, an instinct reflected in the half-finished garments around the room. Tucked into a corner, a dress featured a sand-hued bodice spangled with dozens of hand stitched puka shells, a sophisticated take on Waikīkī’s famous shoreline. The dramatic silhouette — cinched waist, pannier hips — revealed an eye for contemporizing the historical, a characteristic quickly becoming among Ahuna’s signatures.

The frenzied state of the place was understandable. In four days, Ahuna would present the first ready-to-wear collection of his fledgling eponymous brand. “This collection is the learning process. Everything has been a new experience,” he said, energetically, despite an oncoming weariness, no doubt a consequence of the last few months of work. “I really love putting myself in uncomfortable learning places because it’s like, ‘Oh, I’ve never felt this before. I’m going to figure it out.’”

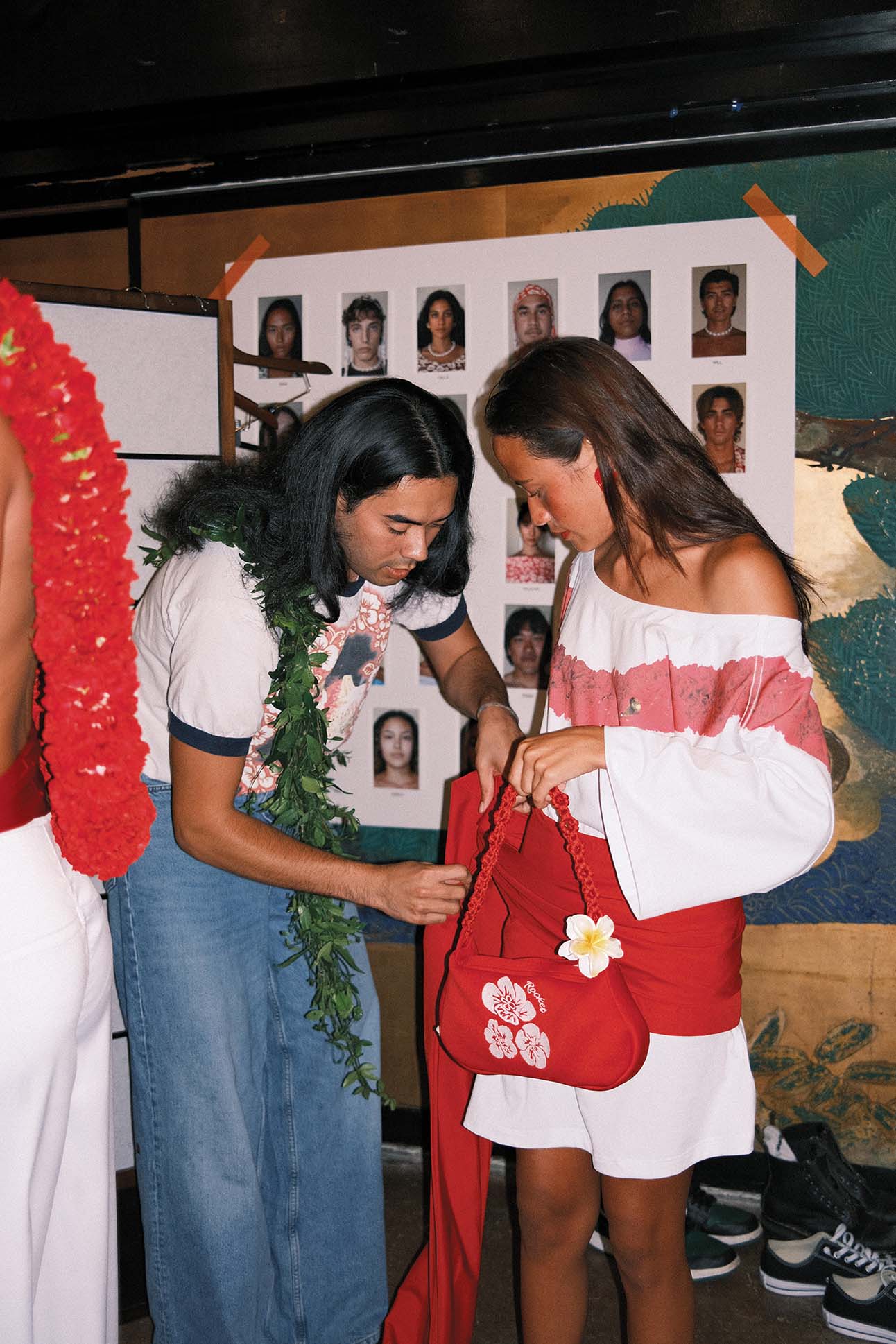

That following Saturday, the show’s crowd of invite-only guests trickled into the hotel’s second-floor ballroom, greeted by a host in a see-through holokū designed by Ahuna. Everyone was clad in bold, maximalist aloha wear prints, a panoply of island-style Sunday’s best. The usual coterie of Hawaiʻi’s fashionable set — creative directors, local influencers, and artists, including a writer covering the show for a piece in Paper magazine — mingled alongside the designer’s family and friends, some of whom flew in from other islands like proud supporters at a graduation. The duality in the guest list manifested a particular crossroads in Ahuna’s career: a local kid striving to break through the fashion industry’s upper echelons.

Ahuna’s first ready-to-wear collection was inspired by — and a subversion of — the semiotics of Waikīkī.

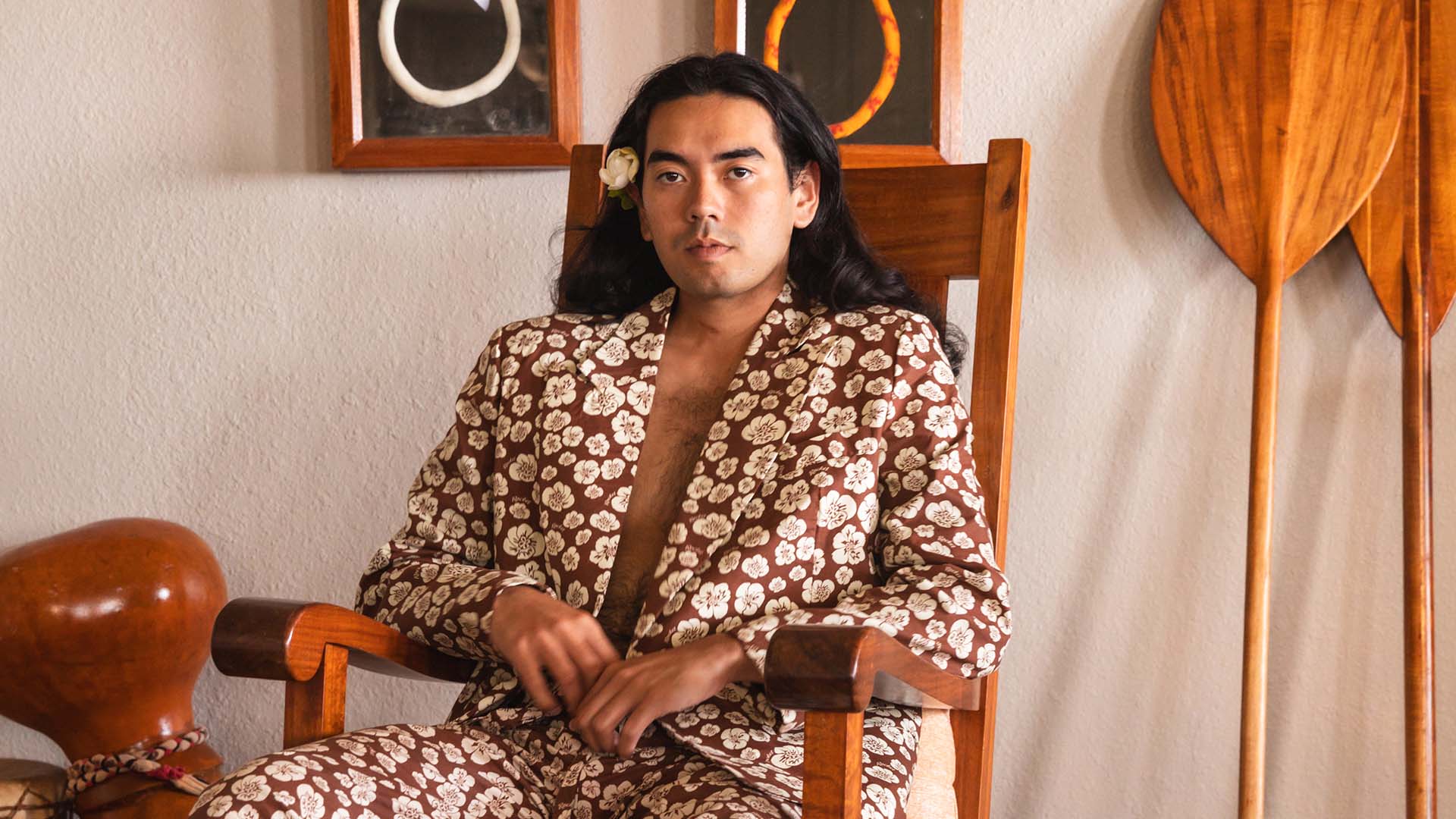

As the sun set, models glided down the runway to a custom soundtrack of piano keys and steel guitar chords reminiscent of hapa haole melodies. Inspired by the runway’s location, the show both celebrated and subverted the semiotics of Waikīkī. A duo in a his-and-hers ensemble parodied tourists with an affinity for matching aloha wear. Skull-hugging swim caps and preppy rugby sweaters referenced the old beach boys, with Duke Kahanamoku receiving a nod in a sculptural dress designed after his iconic alaia board. Most notable, though, was Ahuna’s take on the island’s most enduring fashion icon: the aloha print. Oversized blazers and boxer shorts and skin-tight lycra dresses were emblazoned with a print he designed for the show, replacing the generic, non-native hibiscus with a place-appropriate hau flower. One look took the aloha shirt silhouette to hyperbolic proportions, styled backwards as a floor-length dress.

The collection was Ahuna’s largest endeavor to date. He graduated from the Fashion Institute of Technology in 2022 with a handful of garments based on drawings of larger theoretical collections, the bulk of which only existed as drawings on the page. Even his first collection, “Lau Kī”, presented the preceding fall was largely custom couture accompanied by a small run of screen printed shirts that felt more like art show merch than of a bonafide brand. This latest collection, titled “Kaimana,” however, meant showing 25 individual looks as one cohesive narrative, 11 of which were ready-to-wear garments available for order immediately after. But if Ahuna was at all overwhelmed, he betrayed no sign of it. There was a drive in the way he approached his work — a consequence of having Scorpio as his astrological “Big Three,” or of growing up with competitive brothers, according to his mom. “Whatever’s gonna happen is gonna happen,” he tells himself whenever doubt starts to creep in. “You just gotta trust the process and go for it.”

The 22-year-old had always been a quick study. At 10, Ahuna became obsessed with lei hulu after seeing his mom, Kanoe, making one for a Daughters of Hawaiʻi event. The vividly plumed pieces have long been admired for the patience and precision they require; a single lei hulu often needs a hundred feathers to complete. “He wanted to do it so badly,” Kanoe said, recalling how her son begged to be taken to a class. But Kanoe, an educator who has been instrumental in the development of Hawaiian charter schools since the ’90s, knew she couldn’t send Ahuna to just any lei hulu workshop. She approached Paulette Kahalepuna, who she described modestly as “a traditional lei hulu maker, very famous in Kapahulu.”

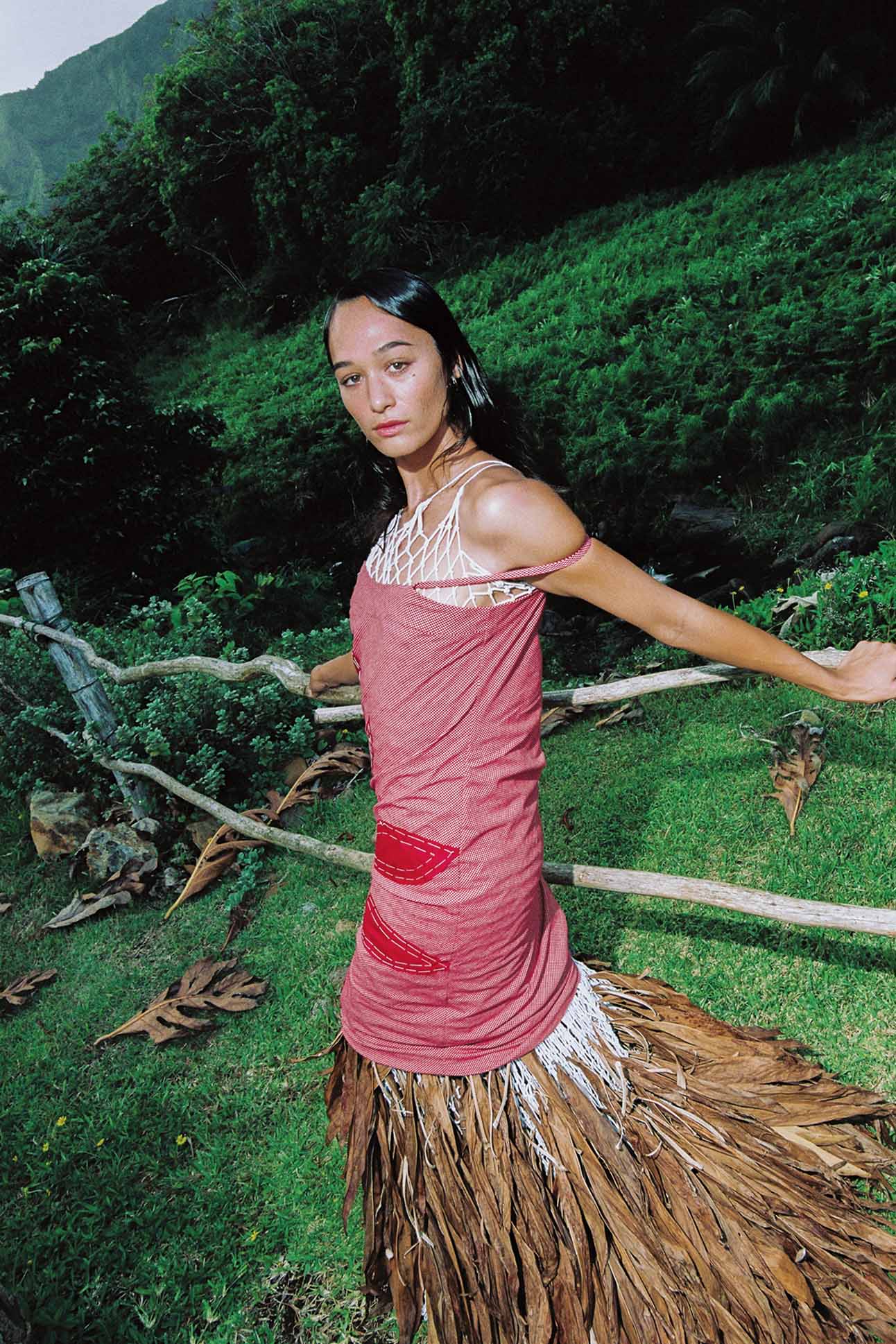

Looks from “Lau Kī,” a collection inspired by the ever-versatile leaves of the tī plant. Images by Cole Turner.

A generational master feather-worker, Kahalepuna was teaching and selling her creations at Na Lima Mili Hulu Noʻeau with her mother, Mary Lou Kekuewa, who published the first written manual on lei hulu in 1976. It was the equivalent of asking a first-chair symphonist to teach your kid their first music lesson. Kahalepuna, at the time, deemed the young Ahuna too green. “I don’t teach this young,” she told Kanoe, proclaiming she didn’t instruct anyone under 13. Nevertheless, Kanoe came back every summer, with an eager Ahuna in tow, and year after year, Kahalepuna turned them away. Then, when Ahuna turned 12, Kanoe bent the truth slightly to enroll him a year early. Finally, Kahalepuna acquiesced.

Ahuna proved to be prodigious, quickly taking to the artform. Before long, he became one of the youngest students to receive an ‘ūniki, or graduation ceremony, from Kahalepuna for mastering the craft. Today, his lei hulu are framed and hung in a place of prominence at his tūtū Reynette’s home in Papakōlea homestead, where Ahuna now lives. And each year, he teaches seniors at Kanuikapono Public Charter School, the Kauaʻi school that Kanoe directs, to make lei hulu for their graduation.

Ahuna’s childhood was often punctuated by similar cultural christenings. Kanoe and her husband, Dan, moved the family — a daughter and four sons, of which Ahuna was the second youngest — to Kapaʻa, Kauaʻi when Ahuna was two, taking posts at a new charter school on the island. In 2010, at the age of nine, Ahuna began dancing competitively with Hālau Ka Lei Mokihana O Leināʻala, whose kumu hula Leinaʻala Pavao Jardin remains a regular competitor at the Merrie Monarch Festival. It was in hula that his interest in design and fashion emerged, inspired by the intention necessary in every part of a performance. “Kumu hula are literally creative directors. They have to style, choreograph, compose sometimes, and tell a story. It’s like having a fashion show at Merrie Monarch,” he explains to me when we meet up again two weeks after his runway show, in Papakōlea. “My favorite aspect of hula was going to learn about somewhere, understanding what represents that place, and then building that garment, that dance, those facial expressions. And it was like, ‘Wow, that’s something I want to do.’”

Hula cultivated a formative grasp of his culture and history, later deepened by an after-school program his mom founded in his early adolescence. Three days a week, Ahuna and a dozen other students from Hawaiian immersion schools would be shuttled around Kauaʻi in a 14-passenger van where he “would learn about the dirt here today or learn about the leaves in the mountain or every star at night,” he recalls, attributing that culturally rooted education to his overall design approach and aesthetic. “It was such a grounding thing to have experienced over the years.”

Among the collection’s stand-out looks was an oversized red carnation-print shirt, a call-back to the golden age of Hawaiʻi travel, with a trailing cummerbund as a pseudo skirt.

In November 2022, Ahuna posted photos of his FIT capstone project on Instagram. The model was bound in a bodice of multicolored taffeta, with hundreds of individually woven strips in an uncanny mimicry of ʻulana lau hala. The sunset-hued skirt billowed out from the waist down as if a flower unfurling into full bloom. “I didn’t expect it to have that much of an impact,” says Ahuna. Truthfully, he had been too overwhelmed by the project, which necessitated learning lau hala techniques and countless hours in the studio perfecting the lattice pattern, to think about the publicity it could get. He was also worried about its public perception, knowing the weight that such a traditional artform carried. Yet, the garment quickly garnered attention on social media, amassing thousands of likes. One comment read, “You implement culture so seamlessly into your work.” Another: “Where can I buy a corset or dress like this? I’ll pay anything.” The dress was awarded the Critics Choice Award among FIT’s capstone presentations and displayed at the Graduating Student Exhibition.

More than the accolades and likes, however, it revealed Ahuna’s design sensibility, showing an early yet astute ability to marry haute-couture concepts with Hawaiʻi’s cultural tapestry. It’s a fashionable tradition that Tory Laitila, curator of textiles and historic arts of Hawaiʻi at the Honolulu Museum of Art, says has always been natural to Hawaiians. Popular perception regards their transition into Western-style clothing as a result of colonization, but according to Laitila, “[Hawaiians] knew what they were doing. They wanted the newest fashions,” and their adoption of the latest styles was less a force of assimilation than of a desire to remain en vogue.

This history is where Ahuna mines much of his inspiration. One can see parallels in his favored silhouettes (corseted waists, dome-shaped skirts) and aesthetic touches (ruffles, embroidery, elegant lines) and the garments of postcontact aliʻi. “Everything in Hawaiian fashion has that little Vivienne Westwood touch,” he says, referencing the British designer who subverted traditional Elizabethan and Victorian looks. “Everything is so elegant, that’s probably one of my favorite things about our aliʻi.”

“Clearly, he knows his history,” Linda Arthur Bradley, a scholar of Hawai‘i apparel and textiles, tells me upon reviewing Ahuna’s designs. “He’s trying to blend fashion innovation and Hawaiian tradition. That’s going to be a tough one to do, but he’s doing it.” Bradley references a look from “Lau Kī” — a red zip-up corset and a netted skirt hemmed by a cluster of dried tī leaves — that transforms the utilitarian ahu laʻi, or tī leaf capes, of old Hawaiʻi into chic evening wear. (The singer Chardonnay Pao wore a custom version of the dress to the 2023 Nā Hōkū Hanohano Awards.)

“What sets him apart is he’s able to take these ideas and bring them to life,” says Puna Joon, who for the past year has been the brand’s stylist and Ahuna’s closest collaborator. “Everybody has great ideas, but bringing them to life is the harder part. Even sometimes he surprises me. Then he brings it to life and I’m like, ‘Oh my god, I get it, I see it.’”

When I first met Ahuna, in the second-floor ballroom a few days before the runway show, the space was functioning as a temporary studio for fittings while the young designer finalized the collection’s looks. After the last male model arrived, Ahuna scanned what was left of the collection. He still had an outfit he was dying to try, except he hadn’t found the right talent to make it work. He pulled the red boxers from the rack and grabbed some leather platform sandals emblazoned with the same print. Was the model game? Yes. When he came back into the room, the easy masculinity with which the model arrived was replaced with an elegant androgyny. Ahuna nodded his approval: “I’ve been looking for someone with a fragile masculinity.” Later in the show, the model stepped out with blushed cheeks, glossed lips, and a red purse in hand — a daring burst of gender-bending within a relatively restrained lineup.

Crucial to Ahuna’s personal self-expression, this fluidity in dressing is just beginning to manifest in his brand, yet is something Ahuna sees as a key aspect moving forward. It’s also the most original aspect of his evolving aesthetic, one that has been absent from Hawaiʻi brands. In feminizing an aloha shirt as an evening dress or queering a model for the runway, Ahuna is testing the boundaries of aloha wear, an industry that remains decidedly binary. He’s not entirely sure if the local market is ready for it, though. “People here will either give you the gnarliest stares or the most slightly homophobic comment ever,” he says. “I kind of live for it in a way. It’s so driving to be pushing people’s perspectives.”

Growing up in a small island town made it difficult for Ahuna to explore his genuine self. Though he openly identified as gay by senior year, he found himself sticking to heteronormative gender constructs like playing sports or dressing conservatively. “On Kauaʻi, who was a fashion designer, you know? All of my friends are boar hunters, football players, surfers,” he says. It wasn’t until he got to FIT (after a short stint at Irvine Valley College studying international business on a volleyball scholarship) that he began to feel comfortable with his sexuality. By the time he graduated, he had a cozy side hustle making customs for drag queens, which “actually helped me to start charging at a price point that I felt comfortable with.” When he flew back home in 2023 to attend Merrie Monarch, he connected with Joon and immediately saw parallels in their upbringing and approach to fashion as a mode of gender fluid self-expression.

Everything in Hawaiian fashion has that little Vivienne Westwood touch.

Rocket Ahuna

A look conceived by Joon for the fall show holds a particular place in Ahuna’s heart. It was of his oversized red carnation-print shirt, a call back to the golden age of Hawai‘i travel, styled off-the-shoulder with a trailing cummerbund as a pseudo-skirt. “It doesn’t only represent me, but so many more kids here that had to experience the same things as me and want to pursue these things,” Ahuna says, his throat catching on tears. “It’s just fun to be with someone that constantly gets me.”

That Merrie Monarch trip unintentionally ballooned from a week to a month to a year. Now, he can’t imagine moving back to New York any time soon, especially with how well received his latest collection was. For a week, though, he had been recuperating on Kauaʻi to escape the overwhelm that hit as soon as the last model walked off the runway. The show was done, sure, but now there was an online store to launch, photos to post, and orders to fulfill. “All my friends were like, ‘We’re going to Kokeʻe because there’s no service and you need a break,’” he recounts, laughing.

But the holiday offered more than a respite. Amid stretches of lush verdure and Kauaʻi’s slow-going ease, Ahuna found fertile inspiration for his next show, inspired by the botanical allure that enraptured him as a child. And he’s eager to start, having already drawn some concepts over the weekend. “I’m ready for it,” he says, that familiar zeal back in his eyes. “I’m really looking forward to my next show now that I’ve felt it. I’m going to be doing this forever, twice a year. Let’s do it.”