For Barbara Pope, books are more than the spaces they inhabit. They’re reservoirs of living cultures.

Images by Chris Rohrer

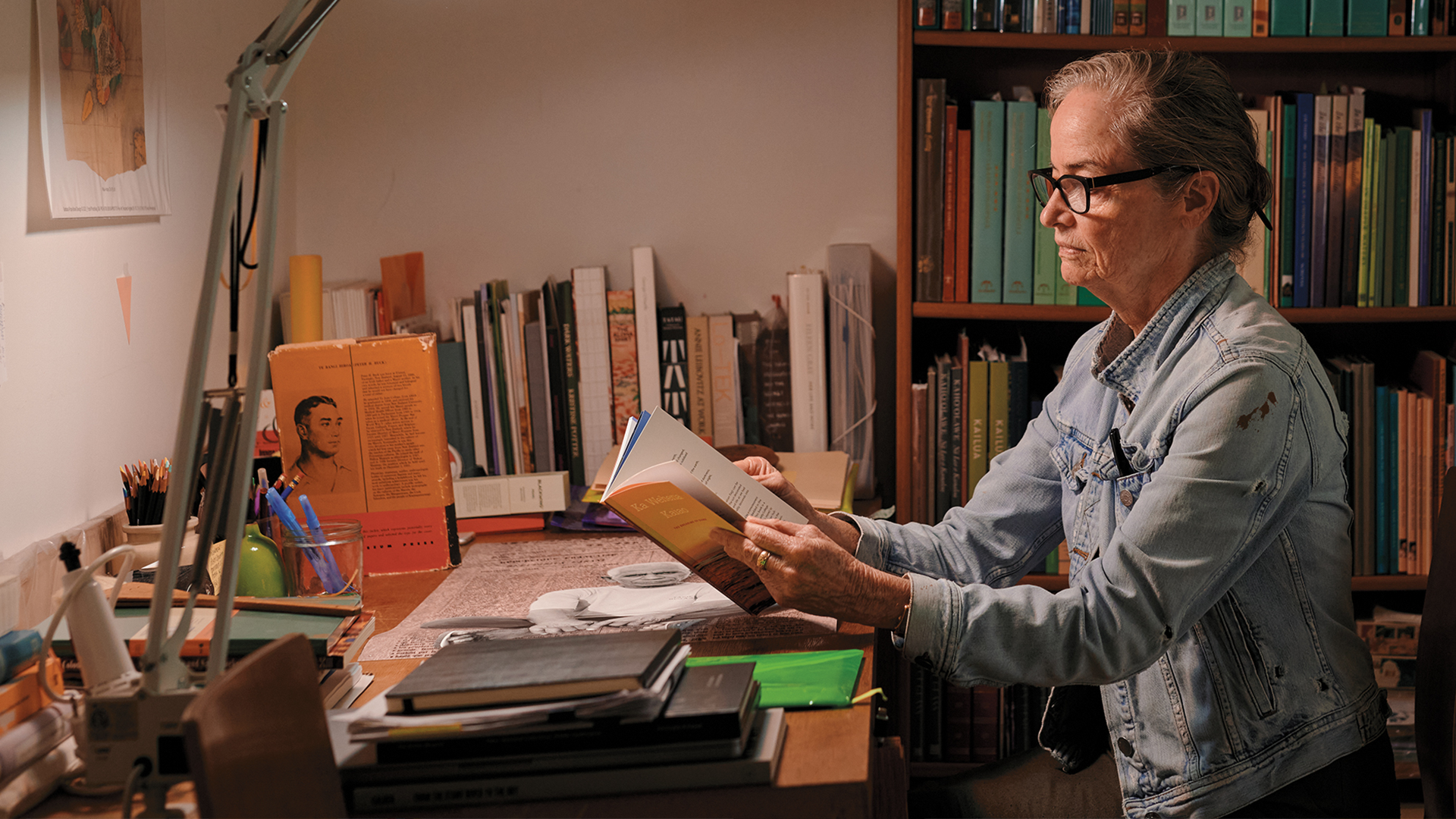

When I first meet the book designer Barbara Pope, on a summer afternoon at her Nu‘uanu studio, she is juggling so many projects she nearly cancels our interview. “I can barely remember my own name,” says Pope, who, along with a lean staff of three, are in the throes of assembling a literary arts exhibition for Festival of Pacific Arts and Culture, the world’s largest celebration of Pacific Islanders, held for the first time in Hawai‘i this past June. In her queue, there’s also a bilingual English-Hawaiian book on the writings of Kamehameha dynasty advisor John Papa ʻĪʻī; a retrospective on the Ossipoff jewel, Liljestrand House; a pocketbook compendium for Windward Community College on Hawaiian protocols; a catalog of 20th and 21st century shell lei by Niʻihau artisans.

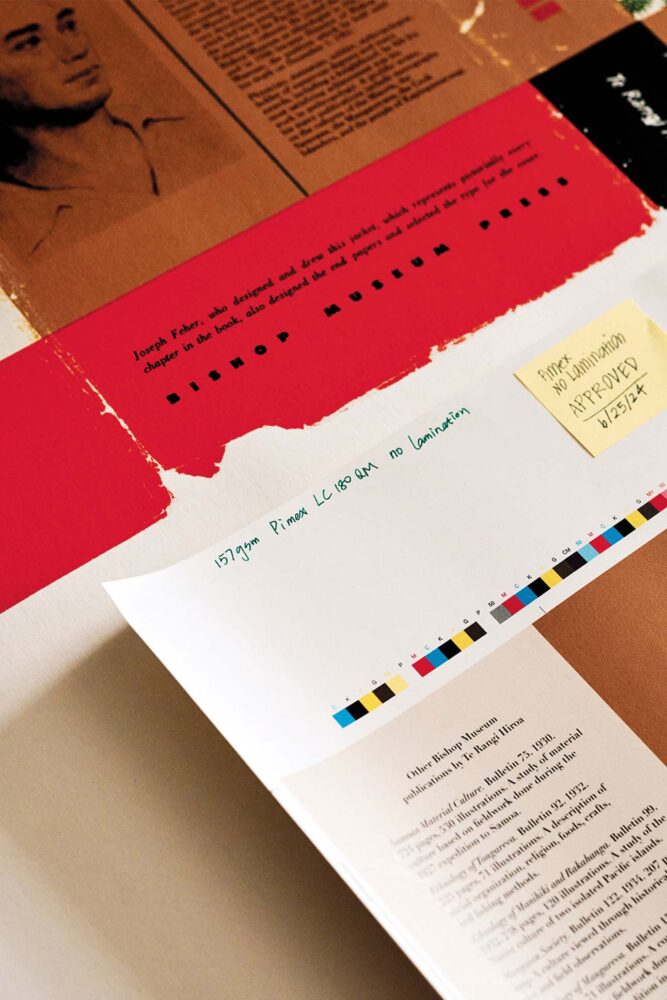

“If you like,” she adds, “I’ll show you something else that’s fun.” Pope leads me to a back office where she unfurls a sheet of opaque glassine paper, revealing a vibrant silkscreen reprint of the book jacket for the seminal 1950s instructional, Arts and Crafts of Hawaii, by anthropologist Te Rangi Hīroa. Pope and her team took great pains to preserve the jacket’s original design by watercolorist Joseph Fehér, whose mid-century prints of Hawai‘i enticed travelers the world over to visit the islands, by scanning the one copy they could find at Bishop Museum, then enlisting a Los Angeles-based silkscreener to reproduce its layers of blocky graphics. “It was really a tour de force to do this, and I’m incredibly proud of it,” she says.

Although her company, Barbara Pope Book Designs, is noted most times in a modest corner of a book cover or listed unobtrusively in an acknowledgements page, Pope’s work has outsized influence and has propped up the canon of Hawai‘i and Pacific Island literature for more than four decades. Many of the texts that pass her desk are grounded in cultural tradition, the result of growing up in Maunawili in the 1960s surrounded by a tight-knit community rooted in agriculture. Pope remembers exchanging eggs, milk, beef, and produce with her neighbors, many of them kuleana families with deep connections to the land. “People engaged in a rural lifestyle seemed to have an innate responsibility for the land itself, caring for the watershed, the kalo, the ancient sites or stone walls,” she says. “There was a really healthy exchange that I saw, with benefits both to the environment and to the families themselves.”

Books have transformative power. They enable a community to come together to say for themselves, ‘This is who we are, this is where we come from, and this is what’s important here.

Barbara Pope

In 1975, Pope left Hawaiʻi to study at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, before moving to New York to attend Columbia University a year later. Her first official foray into design came while she was teaching figure drawing at Columbia in 1983, when the opportunity of a lifetime came knocking at her door. It was Andrew Elston, who was then the press director of Bishop Museum’s publishing arm: Would she like to design a new book with the family of Mary Kawena Pukui, whose Hawaiian Dictionary had long been — and remains today — the definitive authority on Hawaiian language? Although she wasn’t formally trained in it, Pope always had an affinity for design and typography, and she immersed herself whenever she could in advancing that interest, whether perusing Columbia Library School’s rare book collection, taking summer classes in printing at Rochester Institute of Technology, or just “fooling around” with drawings of letterforms based on the Hawaiian language.

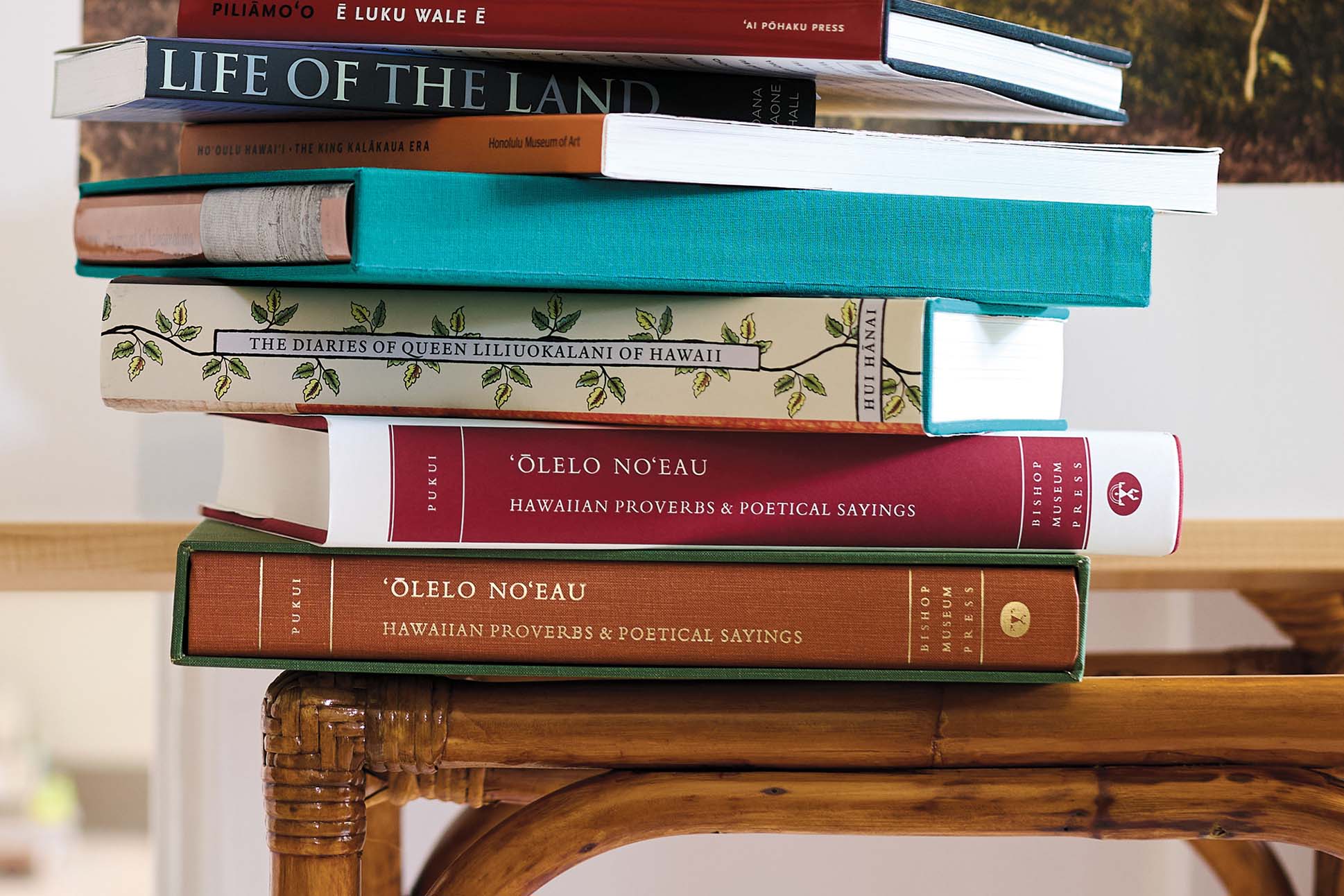

The book, as it turned out, would be ʻŌlelo Noʻeau: Hawaiian Proverbs & Poetical Sayings, Pukui’s groundbreaking tome of Hawaiian aphorisms, quips, and idioms amassed over the course of her lifetime and compiled by her daughter, Patience “Pat” Namaka Wiggin Bacon. “It was like someone grabbed me by the scruff of the neck and said you need to pay attention and learn something here,” recalls Pope, realizing the weight of the project. Putting the material into book form and keeping it in print, Pope says, helped to advance the accessibility of the vast amounts of cultural knowledge that, for a long time, was cataloged primarily in one woman’s head.

Since ʻŌlelo Noʻeau, Pope has worked on more than 150 titles under her namesake company, as well as through ‘Ai Pōhaku Press, an independent publisher she founded with Maile Meyer in the early 1990s, just as Congress was finally returning Kaho‘olawe to the people of Hawai‘i and halting the live fire exercises, military trainings, and bombings that had devastated the island since the 1940s. Although protests by Native Hawaiian activists in 1976 thrust the military’s degradation of the island into the national spotlight, there was little visibility of the bombings’ effect on Kaho‘olawe’s terrain. After a yearslong effort, amassing a drawerful of paperwork seeking permission to send photographers to document the island in its entirety, ‘Ai Pōhaku published Kahoʻolawe: Nā Leo o Kanaloa. The 116-page volume introduced the world to the beauty, cultural history, and tragedy of the uninhabited island with images by photographers Wayne Levin and Franco Salmoiraghi.

‘Ai Pōhaku, or “to eat stones,” is a reference to “Mele Ai Pohaku,” the famed mele of resistance, also known as “Kaulana Na Pua,” written by Ellen Wright Prendergast in 1893, shortly after Queen Lili‘uokalani was deposed by the United States. The idea behind the press, explains Pope, “came from that awareness of what it took to get Kaho‘olawe out of the hands of the military … of what it takes to turn the tide on something that is clearly detrimental and destructive to the land.”

Even after reading thousands of pages of text over the years, Pope remains inspired as much by the words that fill her page layouts, as well as those who write them. Two books she worked on — Kailua: In the Wisps of the Malanai Breeze for Kailua Historical Society and Life of the Land by Dana Naone Hall — in fact, gave her the courage to purchase 1,000 acres of commercial land that she will eventually turn over to the state for conservation, as well as to two nonprofits that will utilize it for agricultural and educational purposes. “Books have transformative power,” she says. “They enable a community to come together to say for themselves, ‘This is who we are, this is where we come from, and this is what’s important here.’”