Illustrations by Matt Honda

At the turn of the millennium, the classic escapist cocktails of marijuana, LSD, methamphetamines, Psilocybin mushrooms, and good old-fashioned alcohol were in demand and used with enthusiastic fervor. While this was true around the nation, it was especially so in Hawai‘i—a paradise where drugs could accentuate a Waikīkī stay or offer an easy escape from the harsh, repetitive nature of living on an island.

When outsiders think of Hawai‘i, they envision a certain ideal, one of bronzed, beautiful people smiling and throwing shakas back and forth. That version of Hawai‘i exists, but beneath the illusory veil of swaying palm trees, towering high rises, and sparkling blue-water beaches lies a seething subculture of those desiring to chase the tail of metaphysical dragons and spiritual awakening, struggling against the rising tide of malaise. Beyond the recreational dip into pot-smoking on the weekend or the occasional delve into psychedelics on a day off, there is an alarming truth coming to light about the extent and lethality of Hawai‘i’s growing addiction to prescription drugs.

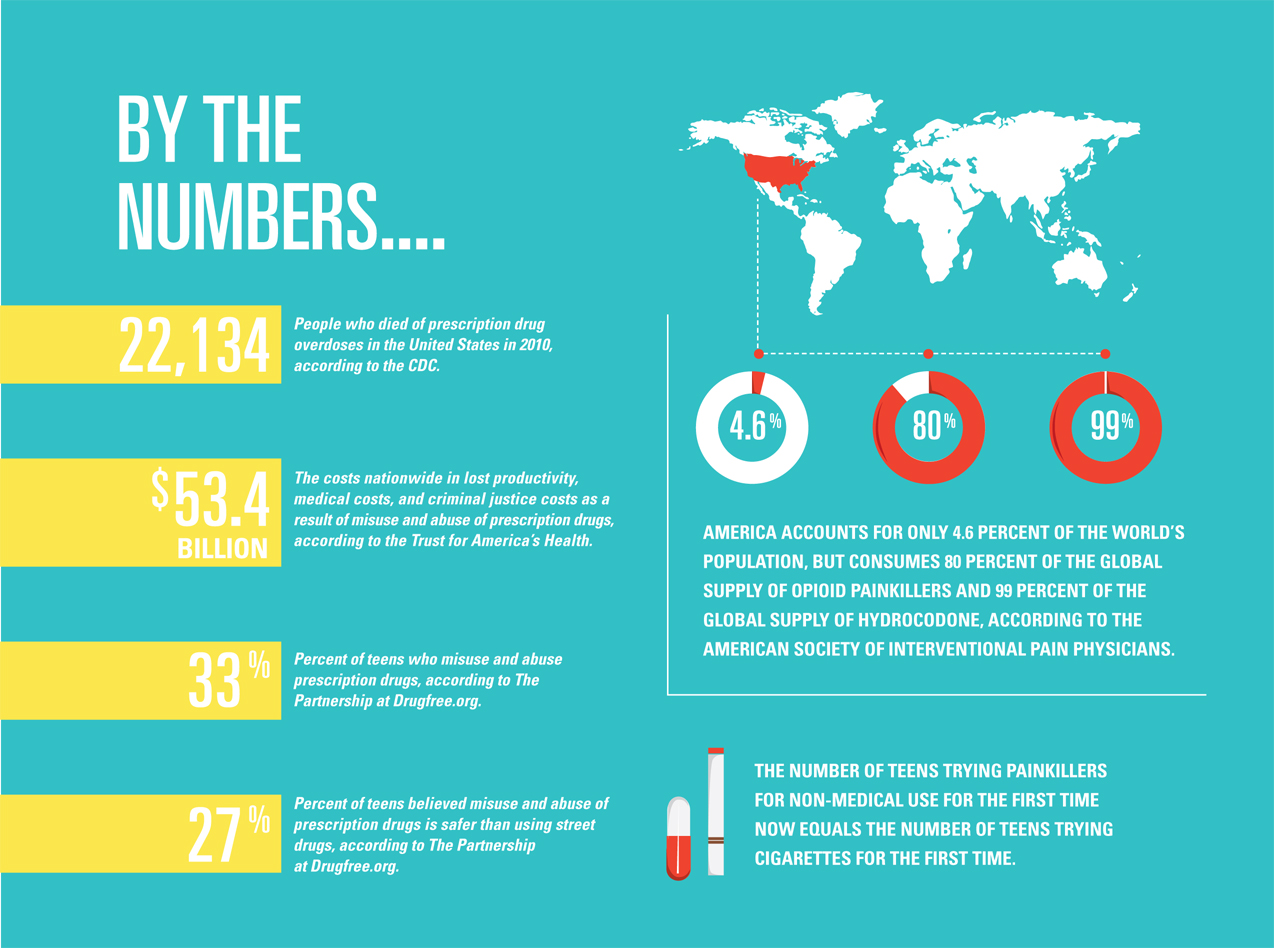

Around the nation, the number of addicts, recreational users, and abusers of prescription drugs has dramatically increased over the last decade. In 2010, the National Center for Disease Control declared prescription drug overdoses an “American epidemic,” responsible for more overdose deaths than heroin and cocaine combined. Sixty percent of drug overdose deaths involved pharmaceutical drugs, with opioid analgesics (painkillers like oxycodone, hydrocodone, and methadone) involved in about three of every four pharmaceutical overdose deaths. It’s estimated that the misuse and abuse of prescription painkillers alone costs the country an estimated $53.4 billion a year in lost productivity, medical costs, and criminal justice costs.

In Hawai‘i, the numbers are just as bleak. According to a 2013 report by the Trust for America’s Health, a Washington D.C.-based health policy organization, drug overdose deaths in the Aloha State—the majority of which are from prescription drugs—increased by 68 percent over the last five years. Matt, a local entrepreneur and friend of mine, was among the statistics.

When I met him, Matt had a sharp mind and was loaded with physical talent. He excelled in most everything he could lay his hands upon. He had the tools to play basketball with guys who were twice his size and yet had the agility and coordination to become one of the most naturally gifted skateboarders at Aiea High School. His mental aptitudes were astounding as well, and it seemed to me that he could run circles around the local drug dealers and tongue-tie the authorities that sought to curtail his extracurricular activities.

He, like many others back then, was an avid marijuana smoker. Where pot sometimes stifles or mellows others, it had the inverse effect on him. He would sit and analyze the minutiae of design and art like a savant. His mind was unleashed from its earthly coil, and he would wax philosophical for hours while deconstructing problems in his mind. Back then, he might have been called a dreamer, an altruist, a complex and versatile humanist. These attributes led him to start his own clothing company, Barely Human, in 2004, with all the dreams and aspirations of breaking into the streetwear scene. He had hopes of changing the way the world viewed itself, and faith that he could inspire and build a better world for his newborn daughter.

In 2006, following a fight outside of a karaoke bar, Matt was seriously injured and one of the vertebrae in his back was permanently disfigured. The doctors advised him that his active lifestyle would further compound his injury, possibly leading to more debilitating results. He was prescribed oxycodone as a way to cope with the lingering pain in his lower back. After six months, he was taken off oxycodone and told to treat his chronic back pain with acetaminophen and other over–the-counter measures. However, already physically addicted to the sedating effects of oxycodone, Matt immediately began to experience nausea, weakness, and the plethora of other negative side effects resulting from withdrawal.

Eventually, Matt’s desperation to alleviate these symptoms led him to what is known as “doctor shopping,” a process of scheduling multiple appointments with a variety of doctors in an attempt to mislead, misinform, exaggerate, or outright lie about ailments in an attempt to take advantage of the ambiguous guidelines for prescribing controlled substances. Since pain is subjective, these types of schemes are just a numbers game that involves playing the odds. A person who is actively doctor shopping will schedule as many doctor appointments as need be until a physician either fraudulently or ignorantly (though with good intentions) prescribes the desired medication.

It didn’t take long to achieve what he needed. After a couple of visits to multiple doctors, he was loaded with prescriptions for oxycodone, Vicodin, and oxycodone hydrochloride, or Oxycontin as it is commonly called. He was stocked with enough pills to sedate a small zoo, but like most addicts, his tolerance had increased, and his addiction had become insatiable. His drug use had extended way beyond therapeutic.

As is the case with most drug abusers, the appetite for louder, stronger, more intense, more visceral, eventually leads most to one of two options. The first option is what most people attempt: They pull back, and rein in these urges. Refocused after their sabbatical to the fringe of commonly accepted debauchery, they muster the strength to switch gears and devote themselves to the church of labor or family or plain sense. This decision is a practical one. This decision leads down the winding pathways to success, stability, and lawful gains. Those who simply cannot abide to put these temptations at bay choose option two.

Matt chose option two.

Ten years ago, Matt’s standard deviation into drug abuse was a joint laced with cocaine, or a drop or two or three of LSD, but with intensified scrutiny on these stock drugs and the increasing ease of accessibility to “legal drugs,” he focused his efforts on the pharmaceutical variety. No longer content with merely sedating his pain, he began applying his industrious and fatalistic tendencies toward swapping his analgesic stockpile for other types of chemistry-altering pills. With prescription drugs able to produce the same effects of archaic drugs but with less oversight and regulation, Matt began to slide further into the abyss of pill-popping and prescription-mixing activities. His company went into default during this time, and he sold off the remaining equipment in his defunct warehouse for more extraneous cash. Barely Human was officially dead.

There are common misperceptions about prescription drugs. A cocaine user knows that he is killing brain cells, and either doesn’t care or is too addicted to stop. The common misperception amongst first time users of prescription drugs is that it is not unhealthy for them, has limited side effects, and in fact, that it may have healing properties. This could be attributed to a variety of factors, from the propaganda of pharmaceutical companies pumping out advertisements of smiling housewives running in white clothing on a summer day while sucking back on some Ambien, to the fact that your local doctor prescribes it to your grandmother.

According to a report published in the Journal of the American Medical Association Internal Medicine, “Most people who abuse prescription opioid drugs get them for free from a friend or relative—but those at highest risk of overdose are as likely to get them from a doctor’s prescription.” (Those considered at the highest risk are those who use prescription opioids non-medically 200 or more days a year.) Because of a belief that doctors will follow their Hippocratic oaths to practice medicine honestly, the average consumer innately trusts his or her prescribing physician.

Matt initially believed the same thing. “I used to think, ‘Why would the doctor give me something that isn’t safe?’” These days, he knows better. Following a two-year stint at Waiawa Correctional Facility for robbery following a dry spell of prescription pills, he began to clean up his act. He goes to Narcotic Anonymous meetings regularly and meets with fellow addicts looking to spread information and awareness. Looking back, he realizes that that he has to accept responsibility for his downward spiral, but has no qualms about giving the powers that be their due as well. “The government and doctors are the biggest drug dealers, and it is absolute shit that doctors get paid by pharmaceutical companies to push their products. When they give you drugs, they always seem to fail to mention the addictive nature and possibly life-fucking side-effects.”

With the prevalence of prescription drugs in the marketplace, abuse among teens and young adults has, inevitably, also increased. Pychostimulants like Ritalin or Aderall, which are used to treat attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, are being snorted or injected to aid in things like weight loss or academic performance, or to achieve feelings of euphoria, as fast as they’re being prescribed. “The dramatic increases in stimulant prescriptions over the last two decades have led to their greater environmental availability and increased risk for diversion and abuse,” according to a report by the National Institute on Drug Abuse. “For those who take these medications to improve properly diagnosed conditions, they can be transforming, greatly enhancing a person’s quality of life. However, because they are perceived by many to be generally safe and effective, prescription stimulants, such as Concerta or Adderall, are increasingly being abused to address nonmedical conditions or situations.”

Research by The Partnership at Drugfree.org supports those perceptions, finding that nearly one-third of parents say they believe psychostimulants “can improve a teen’s academic performance even if the teen does not have ADHD.” Among the estimated 1.1 million people who use stimulants drugs for nonmedical uses is Kaimana, a 22-year-old who doesn’t drink or smoke and rarely goes out on weekends. “The rigors of being in school and working are very taxing, and I just need a little something extra to keep my grades up and keep myself focused,” says the University of Hawai‘i student, who regularly takes Ritalin, one of the most popular stimulants abused among users 12 and up, before midterms. Though Ritalin provides Kaimana with a quick boost (resembling the stimulant characteristics of cocaine), the long-term effects of abuse include permanent damage to the brain and heart, which can lead to heart attack or stroke; liver, kidney, and lung damage; respiratory problems if smoked; tissue damage in the nose if snorted; psychosis or depression.

What might have begun as an honest and thoughtful excursion into the swirling abyss of experimentation and reverie has descended into a growing subculture in Hawai‘i of increased acceptance and use of pharmaceutical drugs, a fever pitch of crushed dreams and frantic grabbing hands. In this paradise, it is easy to become swept up in the scintillating vibrancy of metropolitan nightlife, or the rigorous tribulation of higher learning. The irony is that in our rush to augment the quality of our life and the possibility of our future, we may have unwittingly loosed a dire and even sobering reminder of our own fragile mortality.