Images by Chris Rohrer

pō.polo (n.)

1. The black nightshade (Solanum nigrum, often incorrectly called S. nodiflorum), a smooth cosmopolitan herb, 0.3 to 0.9 meters high. It is with ovate leaves, small white flowers, and small black edible berries. In Hawai‘i, young shoots and leaves are eaten as greens, and the plant is valued for medicine, formerly for ceremonies. Also polopolo. The fruit is hua pōpolo. Because of its color, pōpolo has long been an uncomplimentary term: see lepo pōpolo.

— Hawaiian Dictionary by Mary Kawena Pukui and Samuel H. Elbert

Jarmila Jarmon says her skin carries a lot of history. She grew up in Salt Lake and Pacific Palisades on O‘ahu, and recalls moments of feeling like “the only one.”

When slavery was discussed in class, she says, “People would look at you and ask, ‘What do you think about that?’” Jarmon wanted to talk to other local kids about these things, but there weren’t many kids like her. She also felt her experiences seemed too manini, or small, to discuss with her parents, who lived in North Carolina during the Jim Crow era. Years later, she feels like she has found a group with whom she can share her experiences as a black person: the Pōpolo Project.

Akiemi Glenn, the 37-year-old executive director of the Pōpolo Project, says she started the project in 2015 as a way to learn about the black experience in Hawaiʻi after moving to Honolulu from New York. The black community represented less than 4 percent of Hawaiʻi’s population, according to the 2016 U.S. Census, and Glenn wanted to support her community by creating a space where people could talk about their stories and culture.

“We don’t necessarily have an agenda or really want to be able to have a definitive representation of the black experience in Hawaiʻi,” Glenn says of the Pōpolo Project, which has since grown into a collective of community members with a board of directors. “It’s really about creating a space for us to ask questions about what it means to be here, what it means to be in our bodies here, what it means to be representatives of our different lineages here.”

When Pōpolo Project members talk about their experiences, there is a palpable sense of relief, a meditative exhale in the midst of tension. The opportunity to do so is one some have not had before. Throughout the year, and especially in February (Black History Month) and August (Black August), the Pōpolo Project holds events like film screenings with panel discussions or art exhibits featuring works by members. Glenn continues to seek out stories of black people in the islands and gather research about black history in Hawaiʻi. (The resulting Pōpolo Syllabus is available on the group’s website.)

At early Pōpolo Project events, people shared their painful histories with the word “pōpolo.” Also the Hawaiian name of an indigenous herb with rounded leaves, white flowers, and edible black berries, time and context have given the word an uneasy racialized weight. Although “pōpolo” is sometimes used plainly as a marker of black race, people told Glenn that there are racist connotations to the word. They cautioned her about including “pōpolo” in the project’s title.

As a linguist and a black woman, Glenn understands this difficult relationship with language very well. Elders in her family still don’t like using “black” to reference their community because of how negatively it was used in the past. Yet “black” has undergone a cultural restoration, and is used to symbolize strength, unity, and celebration. The Pōpolo Project aims to add more layers to the word “pōpolo” by sharing the stories of black people in Hawaiʻi. If a harmless word for a medicinal herb can be weaponized as a slur, there is an equal chance that, with the right treatment, it can be used to empower.

Akiemi Glenn

Age: 37 Residence: Pālolo Occupation: Linguist and executive director of the Pōpolo Project

“There’s not one way to be black from Hawaiʻi. It’s not just about being Barack Obama or Janet Mock. It’s about the different experiences. It links to a larger question of what it means to be black anywhere.”

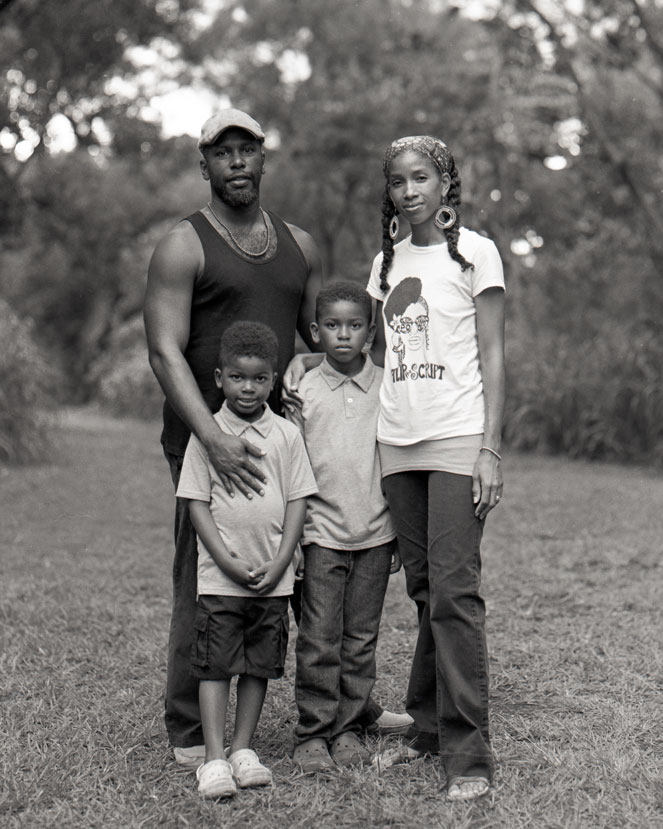

Ade Milligan (age 6) Amari Milligan (age 8) Nicole Maileen Woo (age 43), and Mark Feijão Milligan II (age 41)

Residence: Waiʻanae Occupations: Artists and students

Nicole Maileen Woo

“Art has always also been at the crux of social and political change throughout the ages. And as a potent change agent, art holds the transformative ability to tell the stories of the marginalized with resounding voice and vigor. Stories build bridges. Yet for any story to be heard, a platform is crucial. The Pōpolo Project is such a platform.”

Mark Feijão Milligan II

“As a U.S. Virgin Islander, I see clear connections between the Native Hawaiian experience and the experience of people of the African diaspora. What we experience in the Atlantic, you experience here in Hawai‘i. Both peoples have spiritually rich cultures with strong ties to ancestral energy and ʻāina. Both peoples have withstood colonial oppression and are reclaiming our true legacies with unwavering pride as we move toward the future.”

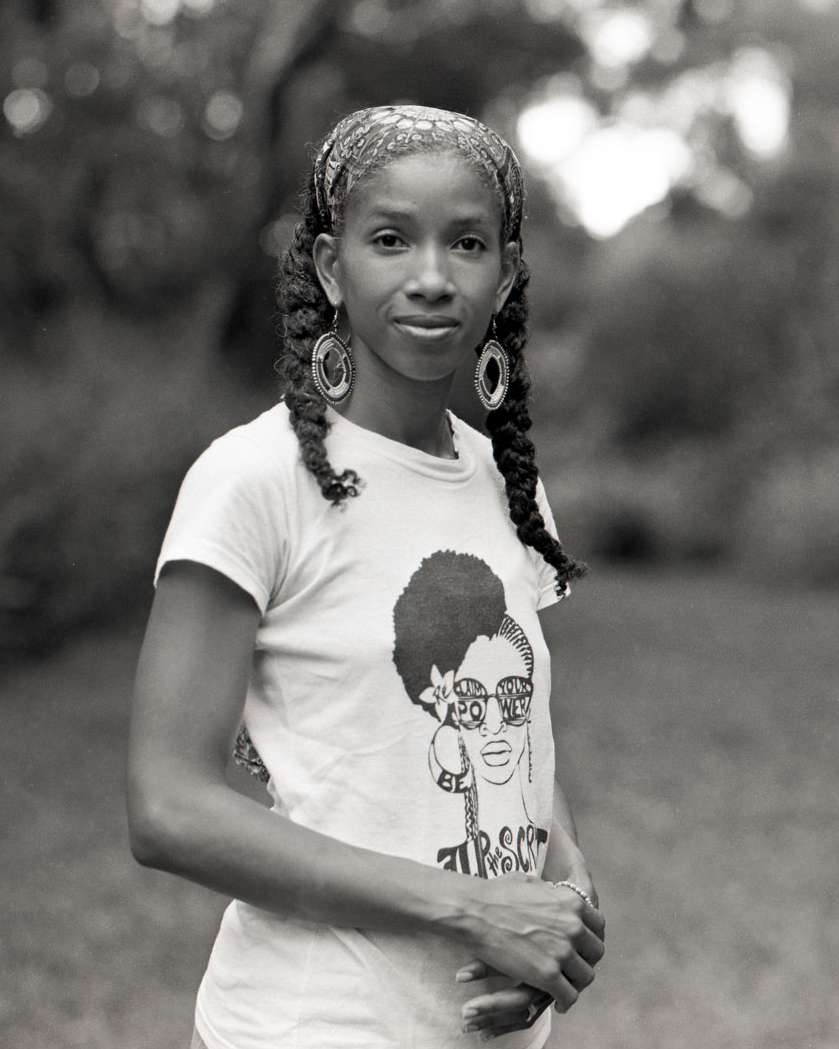

Jamila Jarmon

Age: 35 Residence: Honolulu Occupation: Special Projects at Elemental Excelerator

“I grew up here in Hawaiʻi, and I kind of grew up thinking I was the only one. Hearing about the Pōpolo Project and being able to create community is something I missed as a child. If we can do that now, at least I can have it as an adult, and we can create a community for children growing up in Hawaiʻi who are black.”

Edward Hemphill

Age: 28 Residence: Kahaluʻu Occupation: Grant writer

“Storytelling is so important. The stories you are told about this place often ignore the stories that highlight injustice here. That’s what is really important to me about the Pōpolo Project—making the connections between stories of those impacted by colonization.”

Rechung Fujihira

Age: 35 Residence: Honolulu Occupation: Owner of The Box Jelly

“Being black here is like being a super-minority. When we were younger, there weren’t many black people. So I think our experience is definitely different, and we have been able to share and talk about that. Finding a community has been great.”

Hasan “Sonny” Scott

Age: 40 Residence: Honolulu Occupation: English teacher at Kamehameha Schools at Kapālama

“As an African-American living in Hawaiʻi, I always appreciated when I saw my people out here, and I knew I wanted to connect with them and be able to expand that familiarity that we share. There’s nothing like being yourself around your people.”

Serena Michel

Age: 22 Residence: Kaimukī Occupation: Student at University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa

“Before I moved here, I felt that I was always Dominican, but no one had ever given me permission to go back in time and connect to that—not even myself. So when I came to Hawaiʻi and saw how much ancestry and genealogy is so important here, I finally felt I could give myself permission to travel through the histories of colonization and trauma and revive that history through my writing.”

Learn more at thepopoloproject.com.