Illustration by Mitchell Fong

When I left Hawai‘i to be a writer, my carry-on was organized something like this: a) Hawai‘i driver’s license; b) receipt of final paycheck from previous employer, just in case it didn’t go through; c) four composition books brimming with empty pages waiting to be wildly scribbled in; d) those paperbacks with underlined sentences that, at the time, meant everything to me.

When you’re relocating your life, it can seem a waste to allocate precious real estate in your luggage to Joan Didion’s The White Album or Bruce Wagner’s I’m Losing You. My reasoning was less sentimental, more plain and ordinary—these books were for work, the work I was looking to get as a writer in Los Angeles.

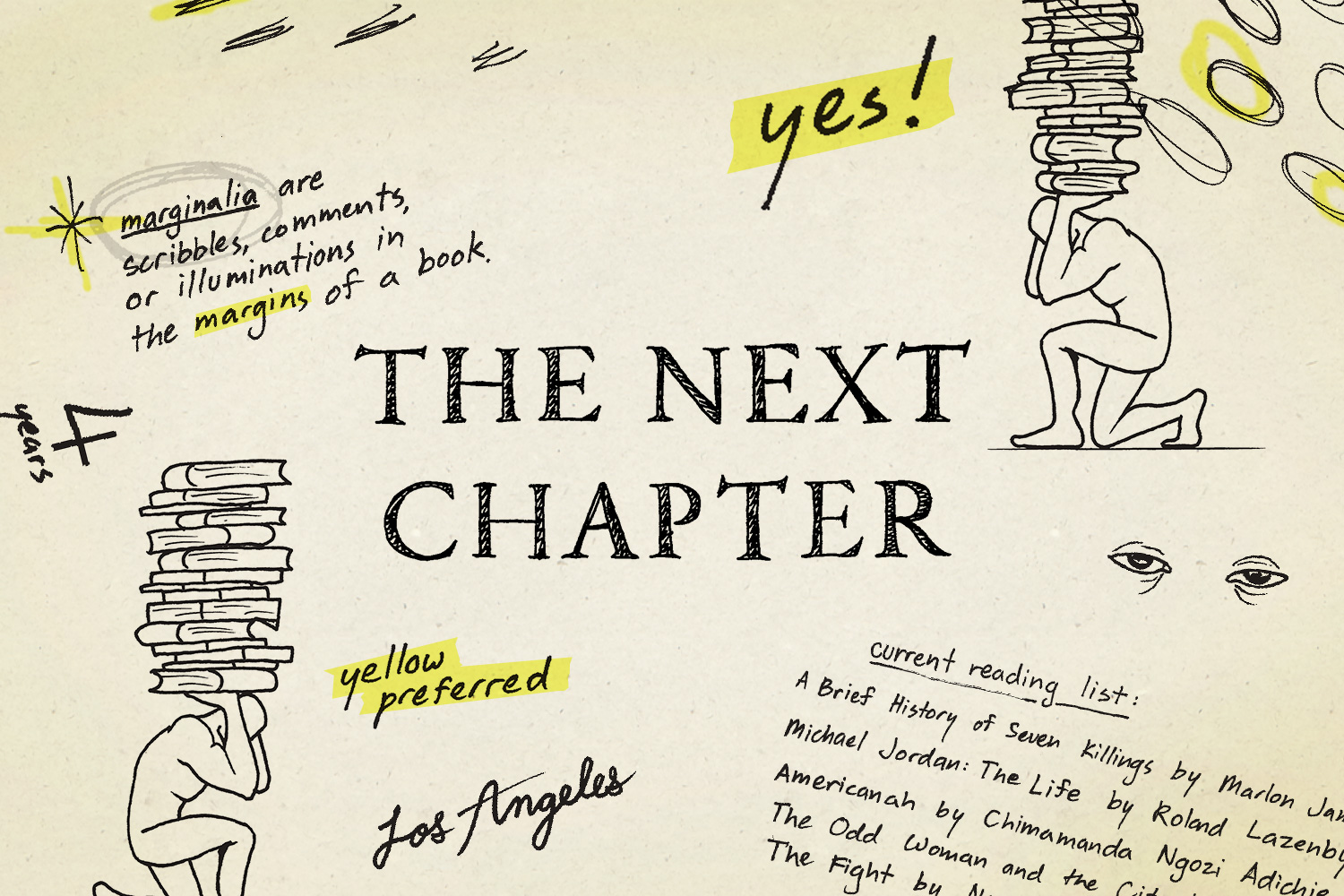

But having those books also helped drive home this notion of myself, the protagonist who loves a bad analogy, moving on to the next chapter of his life. I didn’t just want these books—I needed them to keep me going. I needed the highlighted sentences that sparked realization and recognition, and the stray words that I had circled to remind myself to look up their meanings, as if corralling them into my vocabulary. I have this thing about forgetting, and I never want to forget.

Sometimes it feels like I could rip out all the pages I’ve ever made a notation on and staple them together into a single cryptic, sacred text. Of course, in reality, how rude! Cruel! Like picking only the parts of people you enjoy and discarding the rest—keeping the quick wit of a friend who consistently makes you laugh over pūpū, but not the part where she’s routinely late for the reservation. The important books always feel like people to me, like someone I want to be around. You need the whole to truly understand them. You need to discover that turn of phrase that leaves you undone, wondering, how’d she do that? You need the word that persists even after you’ve moved on to the next page, filling some small cavity in you with enormous feeling.

Four years after hauling these books across the Pacific Ocean, the paperbacks went into another suitcase, this one headed back to Hawai‘i. While unpacking in Honolulu, I flipped through them again. Every time I encountered something I had marked, it took me to exactly where and who I was when I did so. Show me the jerky line in Glamorama by Bret Easton Ellis, and I can tell you I was in the passenger seat of a car headed to Kamehameha Bakery at 5:30 in the morning. Turn to the medley of exclamation points beside the closing paragraphs of White Teeth by Zadie Smith, and I’m there outside the old Barnes and Noble at Kahala Mall, sitting in the stairwell with the best outdoor lighting at 9 p.m., unable to move until I read the last page.

I returned to old books and notes many times my first week on O‘ahu, trying to pin down who I once was through words glowing in faded highlighter, and reconciling this past identity with who I am today. Growing up in Hawai‘i, the idea that you have to leave in order to do anything creative is instilled early. But somehow, upon my return home, those pencil-scribbled markings centered me. They became the most peculiar and unexpected reminder that maybe we’re all books that can unfold anywhere. I moved back to Hawai‘i to be a writer, and I brought those books with me.

This story is part of our Companions Issue.