The soulful and pertinent artworks of the Hawai‘i Island-artist defies medium and description.

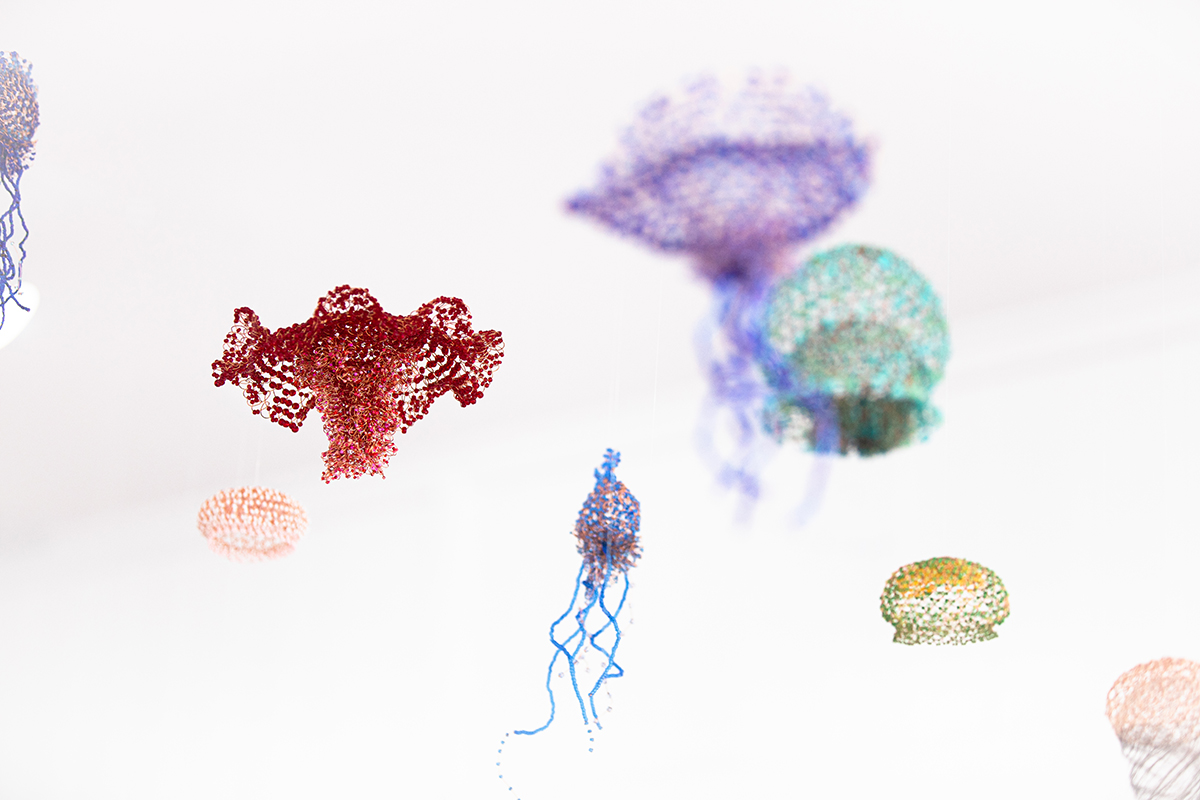

Bernice Akamine has found endless fascination in jellyfish. For the 71-year-old artist, these mystic creatures are a symbol of ancestral connection as well as environmental imbalance. When I spoke with Akamine from her home in Volcano, Hawai‘i Island, she was finishing Pololia, a series of 35 jellyfish sculptures made of finely crocheted copper wire and glass beads for Above the Equator, the new contemporary art gallery and project space in downtown Hilo.

Though best known for her socially engaged projects, it was during this past year of isolation that Akamine turned her focus back to making small, meticulously crafted art objects with nothing more than her two hands.

In the Kumulipo, life begins in a dark, primordial slime with the creation of a single floating coral polyp that anchors itself to the seafloor and begins to grow. (Genetically, these coral polyps are microscopic organisms closely related to anemone and jellyfish.) Recently, studies have shown large increases in jellyfish populations around the world. Jellyfish thrive in temperate and warm conditions, where they can reach sexual maturity quicker.

When the conditions are right, jellyfish can quickly spawn and multiply in a short period, especially when their populations are left unchecked by larger predators. These large and increasingly more common blooms are directly linked to an imbalance in marine ecosystems, as well as declining fish populations, especially in already over-exploited fisheries.

“We don’t think about how we’re impacting things,” says Akamine.

And as waters continue to warm, jellyfish blooms proliferate. Jellyfish have unfortunately become an omen of future potential climate catastrophe even if it’s not their fault.

Born on Oʻahu in 1949 and raised in Waimānalo and Kalihi, Akamine, who holds a Bachelor of Fine Arts and Master of Fine Arts in sculpture from the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, didn’t begin her formal Western art training until later in life after raising her family. Early in her studies, she took a glass-blowing class taught by longtime professor Rick Mills in the early 1990s.

“From the moment I stepped into that studio, I was drawn in by the heat and the energy, the movement and spontaneity,” she said.

However, it was during her graduate studies in the late ’90s as an exchange student at California College of the Arts in Oakland where she began to explore the possibilities of a socially engaged art practice. In Oakland, Akamine was an assistant to artist, feminist, and social practice pioneer Suzanne Lacy.

At the time, Akamine was working with Lacy on a project called Expectations, which covered a spectrum of issues around teen pregnancy, from its impacts on the health and education of young women to its role in political stereotyping, lawmaking, and social policy. All of these new experiences sent her practice in a new direction.

Akamine moved home in 1999, to finish her final semester of graduate school at UH-Mānoa. But before returning home, Akamine wrote Kahu Kaleo Patterson, a Hawaiian Episcopal minister and houseless community champion from Mākaha. She wanted to propose a project that would take her and members of the Hawaiʻi Ecumenical Coalition, a network of ministers and churches from around the islands that Patterson founded, to different houseless encampments, most of which were found at beach parks and roadsides adjacent to Hawaiian Homestead communities.

The final work, Kuʻu One Hānau, called attention to the rising rates of houselessness among Native Hawaiians in their homeland. As a part of the sculptural component of her thesis, Akamine created a tent structure whose roof was made of an oversize canvas Hawaiian flag. Finished in 1999, the work was most recently shown in 2019 as a five-part iterative work during the Honolulu Biennial to highlight how Kānaka Maoli are still disproportionately represented in houseless statistics compared to other ethnic groups today.

That year’s biennial also featured another monumental community-centered work by Akamine entitled Kalo. The large-scale installation featured 87 kalo sculptures of paper, wire, and pōhaku. More than just a staple food of the Hawaiian diet, the kalo plant holds special significance in Kānaka Maoli cosmologies. (Hāloa, the first Hawaiian, is the younger brother of Hāloanakalaukapalili, a stillborn from whose grave grew the first kalo plant; kalo is thus considered an elder sibling to the Hawaiian people.)

In Akamine’s piece, the leaves of the kalo plants were constructed from copies of the Hui Aloha ʻĀina Anti-Annexation Petitions of 1897 to 1898, which saw 21,269 Hawaiian Kingdom patriots stand in firm resistance to American annexation. The corm of the kalo was made of a pōhaku sourced from communities in Oʻahu, Molokaʻi, Kauaʻi, Maui, and Hawaiʻi Island. For the biennial, the project was installed at Aliʻiōlani Hale, the site of the 1893 overthrow.

On the morning that the project was installed, over 150 people from across the islands formed a procession from ʻIolani Palace to Aliʻiōlani Hale, following the same route Queen Liliʻuokalani would have traveled from her home to government offices across the street. Each kalo sculpture was carried by kūpuna, ʻōpio, and descendants of those who signed the Kūʻē Petitions and placed in the central rotunda of the building.

Kalo, like much of the work in Akamine’s oeuvre, connects communities across the paeʻāina, across time, and generations, in aloha ʻāīna and ongoing resistance to American annexation and occupation in our islands.

Often, it’s the impactful projects of this scale that require months, sometimes years, of research, development, grant funding, and strong community partnerships to accomplish. But for now, Akamine is taking a pause and finding satisfaction in the solitude of making small jellyfish at her home studio.

“I still make pieces, just to make, for joy. But I always try to balance that with work I feel that is important to give others a voice.”