E heluhelu ma ka ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi (Read in Hawaiian)

When the Navy’s underground fuel tanks contaminated the drinking water for tens of thousands of O‘ahu residents last year, a decades-long debate over militarism, mismanagement, and land stewardship was reignited. A Hawaiian leader invites allies—“anyone who has aloha for this land”—to remain vigilant.

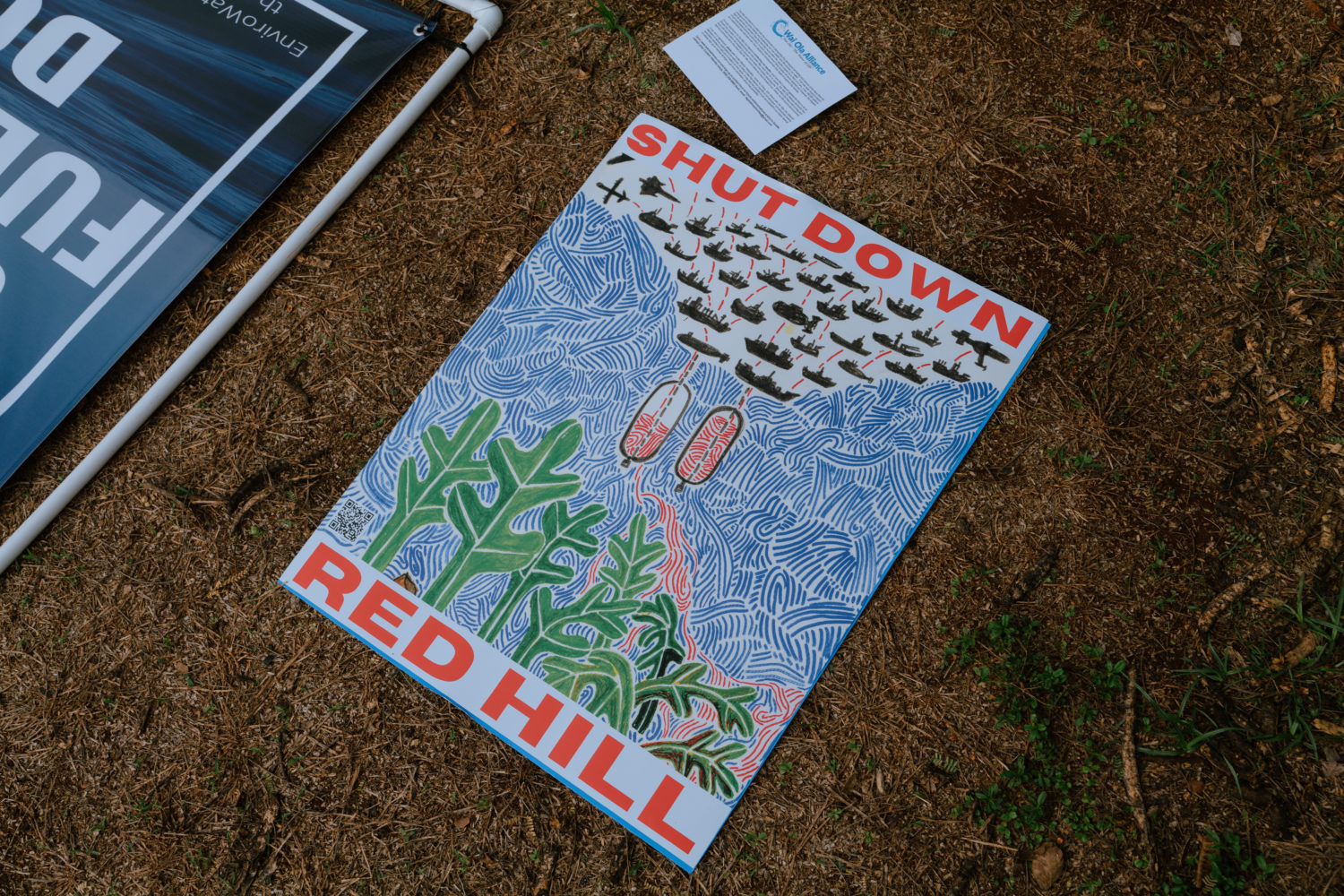

Images by Josiah Patterson

Edited by Matthew Dekneef and N. Ha‘alilio Solomon

English translation by Hilinaʻi Sai-Dudoit

While local environmental justice groups have been pushing back against the Red Hill Bulk Fuel Storage Facility for decades, it would take reports of unexplained illnesses and hospitalizations of residents and intense national scrutiny for state agencies to take meaningful action. Mistrust of the US military’s land management practices has long pervaded many pro-Hawaiian groups as well, inspiring leaders like Kalehua Krug to promote a Hawaiian worldview to guide stewardship; Krug is the principal of Ka Waihona o Ka Naʻauao, a Hawaiian charter school; a traditional Hawaiian tattooist; a musician and composer.

Krug is also part of Kaʻohewai, a coalition that erected a koʻa (shrine) near the front gate of the Headquarters Commander of the U.S. Pacific Fleet, where members regularly conduct Hawaiian ceremonies to frame the ongoing opposition to the U.S. Navy’s 20 massive, steel-lined underground storage tanks through a Hawaiian worldview.

In December, Krug sat down with Flux Hawaii in Pauoa to discuss the recent history of aloha ʻāina activism at Kapūkaki, also known as Red Hill, and remaining hopeful about the future.

N. Ha‘alilio Solomon Welcome, Kalehua. Please explain a bit of your folks’ efforts at Kapūkaki. You said previously that there is a koʻa. What is its purpose?

Kalehua Krug That’s right. We know from looking at the dictionary which Pūkuʻi left for us that the koʻa is a mound of rocks, round stones and coral, and it is built to increase [the yield of] fish or birds. It is also built at the river’s edge most of the time, or near the sea, and that’s exactly how we have it — being that this [koʻa] was constructed in front of the naval base, at the first entrance of the naval base in Kapūkaki. The koʻa was constructed there so that at the first gate, it is seen regularly by those who pass by as a reminder that the ongoing issue affects everyone. The one benefit about it being built there is that there is a stream as well. So, its manner of construction is done according to what we know about koʻa stewardship. But it will attract no fish, or birds, if we do not subscribe to the notion that birds are equal to humans, and fish are as well. Because that koʻa attracts humans, it attracts wellbeing. It draws the attention of the people to stand on the right side of this issue we need to support, regarding the leakage of fuel into the groundwater, which then surfaces in the streams, in water pipes, and in homes where military personnel are living. There are 90,000 people who have been negatively affected by this contaminated water, so that koʻa is an instrument to raise awareness and make people think, so everyone turns and comes to know about this issue — and to also inspire the Hawaiian nation to stand alongside those who built that koʻa together, and to support the side that will resolve this issue.

HS How many years has the fuel been leaking into the water? Do you know?

KK Oh, that’s the question! We know leakage has occurred several times by the year 2000 — this is shown in documents and a few testimonies before the court. In 2014, for example, a significant quantity of gallons leaked, at least tens of thousands that year. And today, more than 100,000 gallons of fuel have leaked into the land, due to the Navy’s mismanagement of those fuel tanks. (Editor’s note: After initially resisting, the Navy will comply with the state Health Department’s order to defuel the tanks and submit an implementation plan by early February; following approval by the Department of Health, the Navy will have 30 days to defuel the tanks.)

HS Who are the people appearing before the court, testifying? You folks? The Sierra Club?

KK Yes. Some university affiliates as well. But really, anyone who has aloha for this land.

HS Yes, and there’s the tricky part. For years, people have been raising great awareness to this problem, yet you folks are met with deaf ears.

KK To be expected, though. One group that was born out of the koʻa’s construction is Kaʻohewai. It is a group where people of different backgrounds come together, including individuals, schools, departments, to cooperate and show the people unity on behalf of the Hawaiian people regarding this issue. Because before the building of this koʻa, Hawaiians were not talking about [this issue] as much as they had about Maunakea. There were thousands and thousands of people who visited the mauna. This, Kapūkaki, is a new mauna for which noses may meet [in greeting], people gather, and unite in aloha for the land.

HS Recently, you folks met with a higher ranking Naval officer?

KK It was only a brief meeting to let them know our thoughts. As usual, there was a lot of smiling, a lot of flattery on their end. I would like to believe that what they conveyed was true, but in spite of their flattery, it is hard to trust them, it’s hard work even considering trusting them, it was hard before even arriving at that meeting. The meeting was simply to show them that we are not afraid to meet with them. We are still suspicious of their actions and their intentions

HS Is there a deity to whom the koʻa is dedicated?

KK An idol was erected which Andre Perez folks carved, beautifully so, that stands in one of Kāne’s likenesses, which was found on Kauaʻi. But that likeness, like the one at the Bishop Museum, is the only one we are familiar with, which stands in the form that is said to belong to Kāne. So its image, its character was used as a means by which Kāne may once again stand. Kāne, Kāneikawaiola. That’s who this is. And it has a keeper to tend to it forever, until the end of [its] life. In this custom, the custom at hand, its care will not degrade following this ordeal. It will be well taken care of. So, Kāneikawaiola is standing in the center of the koʻa, and on its left side, there is a carved stone basin. It’s like a bowl, an ʻūmeke. Some say ʻūmeke, I call it an ipu — ipu wai. That is where water is deposited and fed, so the thing to offer it is water, which is poured atop.

HS You said there was a stream there?

KK Yes, Hālawa.There is not much attention paid to this issue, so, that koʻa, if you can hear its call, it calls out for the people to know of this issue. A koʻa was used instead of an ahu because ahu are, sometimes, carelessly constructed and poorly taken care of, and the ahu is sometimes like a heiau. The koʻa was taken up because it attracts natural resources, whether it be fish, birds, that sort, so, some time ago, we had decided in our conversations regarding the structure that will stand there the koʻa was preferable to the ahu because that kind — what should I say — a stone altar of worship, just like those which stood as ahupuaʻa markers, the type of ceremony it requires is similar to that of a heiau. That is not what we wanted, so this is different. And Kānekoʻa, coral, is a body form of Kāne. It is a body of Kāne, as you can see when you break down some of his names. So the koʻa suits those things, the water of Kāne, coral, and water. Those were our considerations before deciding on a koʻa.

The one thing that lifts my spirits is being reminded of the endurance of the struggle and standing on the right side of it.

Kalehua Krug

HS This question, I bemoan, but how do you go about finding something to raise humanity’s hopes for the future? I was speaking with a friend from KAHEA. She said, “Easy to feel powerless.” That is a place so easy to go to, where the will of a person is destroyed. How do you keep your hopes up?

KK The one thing that lifts my spirits is being reminded of the endurance of the struggle and standing on the right side of it. I tell people that the koʻa, this sort of knowledge started by me observing the carved deities, the images of Kū that were toured and brought through the middle of the crowds atop the mountain, at Puʻuhuluhulu: there were women, children, pregnant mothers, elderly women and men, all kinds of people. And in the eyes of our ancestors, we can say that this is not correct. It is not right. But I am trying now to, and forgive me, for those who are reading and listening, I am not criticizing: I am simply stating, just giving a report about how things happened. But it happened, and our histories were consulted, it was not done that way. It did not suit the ways reported by Malo and Kamakau.

Nevertheless, from the Hawaiian point of view, what good is a worldview? What good is the Hawaiian way of life? This is my perspective, and what I always tell people, is that the most important parts of the language, the knowledge, the teachings, and the wisdom in all of these things, from the Hawaiian point of view, is the understanding that humans are extensions of this Earth. A person is not distinct from fish, from the wind, or from rocks. That type of personification, building relationships with those things as if they are humans, through naming them, talking to them, all of those things, it is a way for us to expand our worldview. And what I am saying, whether it is right or wrong, that is not my point. What I am saying is that such practice is a way for people to connect to the land. So when I consider what happened at Puʻuhuluhulu, and whether those things are Hawaiian, well, it is not the same as what our ancestors left for us. Yet when I ask myself whether the bond between people and land was stronger because of those actions, I would say “yes.” It drew people to gather and it increased appreciation for our gods, ancestors, family guardians, and old Hawaiian practices. And when that kind of reverent knowledge is obtained, such that the bond between man and the land grows stronger. I think that’s a victory. Because we are at war, and this is a war of worldviews, between modern existence, and that of those who came before. Our ancestors shaped their environment for the good of all things. They did not just focus on what humans need. When that decision is made, and this is a difficult question one must routinely consider when making any decisions, if we were to ask if our actions benefit humans alone, or if they benefit the entire natural world. For me, my spirits are raised by thinking this way.

Because I see the problem, it is very easy to lament the actions that took place long ago, or the decisions our aliʻi made in the past. For me, the toppling of the ʻAikapu was one step. Allowing the missionaries ashore, another step — I could list them all. Promoting a literate nation, another step. The Māhele, another step. The overthrow, another step. There were many steps that we now see led to the destruction of our worldview and our thinking. And as much as I’d like to avoid disparaging any part of knowledge, I am saying that by destroying that worldview, the bond between people and land was also severed. A bond like what was forged by the last people to connect to this land. Understand?

HS Yes.

KK In a book that I read — a book that helped me in forming this type of thinking — at the end of the book, a question was asked: With everything that can really bring you down, how does one go on? The answer is that you become the teller of this story. You raise your spirits by telling your story. By standing in front of those reporters and speaking to those people who interviewed me, I felt hope, because I knew people would hear. And that’s all we can do.

Sitting Bull, too, he said that as well. Sitting Bull said some beautiful words to raise the spirits of the people at that time, because the people were leaving, and the buffalo were declining, there was a lot of disease, they were displaced, kicked out of their lands, but he found comfort, because he was asked, “Why do you keep dancing? Why do you keep chanting? Why do you keep celebrating? Why do you keep laughing?” And he responds, “Because that is a part of being Lakota, of being who we are.” Then he said that if he stopped doing those things, and never did them again, he would no longer be Indigenous. So that’s how I like to raise my hopes.

HS It also seems like calling people to join you folks gives you hope. I saw a recording of you speaking. You were being interviewed by a reporter. What was it that he asked you? Anyway, your answer was, “Join us.” What do you think about the people who are able to come and join the movement and those who are not? What do you think about that?

KK Like I said before, this isn’t meant as an opposition to anyone, or any race. This is an objection to a certain point of view. That call for all people to unite, it’s meant to show that skin color doesn’t determine whether someone is invited to help. Their language doesn’t determine whether they are invited. The only thing is that if the worldview resonates with them, and here I am talking about an Indigenous worldview, a Hawaiian one. If you are inspired, then come join us. When your soul is touched, that’s the main thing. That’s the main goal. Grab people’s attention and try, just try, try to form a new worldview, so that our grandchildren will not need to worry about whether life will go on or not. So all are invited to share in this worldview.

HS If you are inspired, then come join us. That’s wonderful. I think such an important idea that came from our conversation was your explanation that this is a war between differing worldviews. Because we often hear the term “culture war” in English, that sort of thing. Every nation has conflict. It is about worldview. About two worldviews clashing.

KK Yeah. Well this doesn’t only apply to America. Because people in China are doing the same thing. People in India are doing the same thing. And we tend to think that the dominant perspective is the perspective that allows humans to rule the earth. We forget, the land is the chief. Yes, that is our war.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.