A certified forest therapy guide explains forest bathing, the art and practice of slowing down.

Upon arriving at our meeting place of Lyon Arboretum in Mānoa Valley, forest bathing expert Phyllis Look invites me into her “office”—a tree-shrouded gazebo near the visitor’s center—where she explains that, despite the name, forest bathing doesn’t involve any water. The term refers to the therapeutic practice of soaking in the forest atmosphere and allowing it to nourish mind, body, and soul.

Look is Hawai‘i’s first and only certified forest therapy guide, but she’s not alone in her conviction that nature is a powerful source of healing. The recent retiree started her company, Forest Bathing Hawaii, after training with the Association of Nature and Forest Therapy Guides and Programs, an organization that has certified more than 700 forest therapy guides in 46 countries since its founding in 2012. As we amble across a sunny, sloped lawn dotted with birds dipping their beaks in the grass, Look is careful to specify that she’s a guide, not a therapist or scientist. It isn’t her goal to convince anyone of the benefits of forest bathing, she says, though decades of research into the practice show compelling findings.

Forest bathing has been around since the 1980s, an answer to the culture of toxic productivity that emerged in Japan during the country’s rapid economic growth after World War II. To address the rise in chronic disease and a phenomenon known as karoshi, or death by overwork, the Japanese government launched a public health campaign to promote forest bathing, or shinrin-yoku, a term coined in 1982 by forestry minister Tomohide Akiyama. Today, there are approximately 100 government-supported forest-therapy bases throughout Japan. Rooted in the notion that humans are wired to thrive in natural environments, where we’ve spent the vast majority of evolutionary history, forest bathing and other forms of nature therapy are gaining traction around the world as a means to cope with the stresses and mental fatigue of modern, urban life.

You May Also Like: The Need to Breathe

“I think slowness is the key,” Look says, pausing in a quiet, shady area downhill of the lawn to present the first of several guided exercises in her forest walk. She refers to these exercises as “invitations.” In this one, which she calls “pleasures of presence,” I’m meant to anchor myself in the present moment through mindful engagement of the senses. “It’s as if you’re a connoisseur of grass,” she says, sipping the air through pursed lips. “Taste the oils in the grass and swirl them around in your mouth. Bring your nose closer to the ground and inhale the secret aroma inside of that dried leaf or those pebbles of dirt. If any of these bring you pleasure, be with that pleasure. Give yourself over to it.”

The pleasure evoked by the smell of cut grass, the breeze on our skin, or the murmur of a distant stream isn’t just in our heads. Researchers have found that people who spend at least two hours per week in nature demonstrate a number of physiological changes, from reduced blood pressure and lower levels of the stress hormone cortisol to improvements in immune function and cognitive performance. In Japan, one of the most densely forested countries in the world, studies have centered on the effects of being around trees—namely, the disease-fighting properties of phytoncides. These airborne compounds, emitted by trees and other plants as defense against harmful microorganisms, are also shown to activate cancer-fighting cells in humans. One study discovered the anti-cancer benefits of phytoncides last up to 30 days after a three-day immersion in nature.

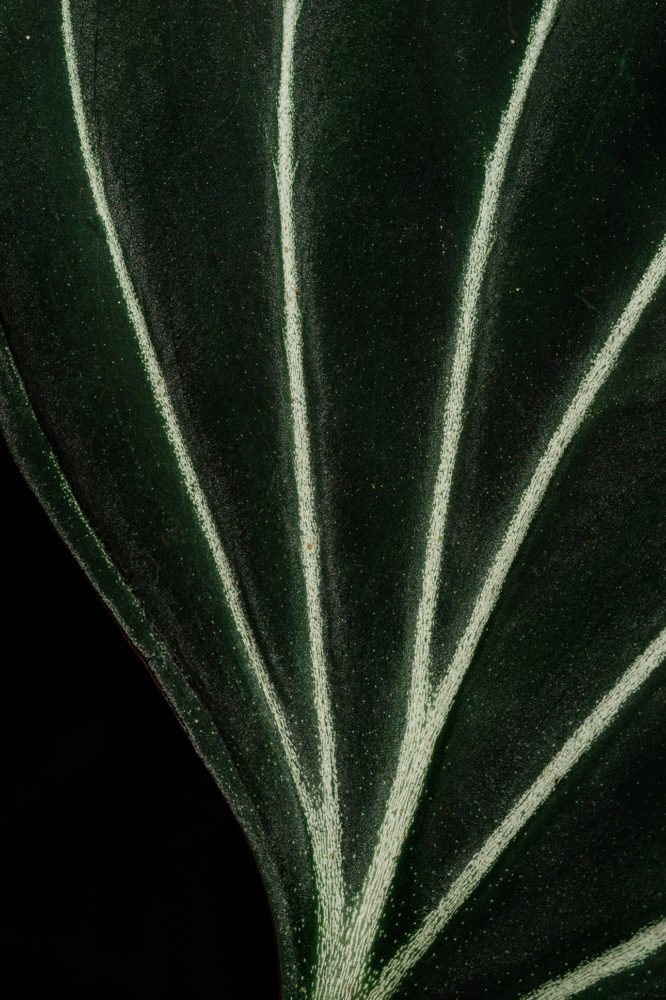

Given that Japan is also the birthplace of Shinto, an ancient faith that recognizes a spiritual power present in the natural world, it’s no surprise that forest bathing advocates often regard nature as both sentient and sacred, a sentiment shared by forest therapy guides outside of Japan. “It’s always the underside of the leaf that has the stories,” Look says, pointing at the veins of a nearby fern. “Imagine that the leaf wants to be seen—that it’s tickled by being observed.”

Wordlessly, we make our way uphill along a gravel path, sunlight flashing on the glossy surfaces of the leaves. A bird lands nearby and warbles from its unseen perch in the trees. Look beckons me over to a dense patch of beehive ginger and, in a sudden movement, shakes the base of one of the vibrant red cones, showering my outstretched hand in the fragrant water released from its bracts. I’m struck by the playfulness of it all. “The benefit of a guide is like having a playmate,” Look says, grinning. “Someone who can say, ‘Try this,’ or ‘Let’s do that!’”

You don’t need a guide to go forest bathing, Look says, but there is value in forest bathing with someone dedicated to your rest and relaxation. A guide can watch the clock, for example, so you don’t have to. “Time is very flexible,” our guide muses amid preparations for a tea ceremony, the last portion of our forest bathing session. “You can completely let go, and that’s really restful for the brain.” It’s fitting, she reasons, that the Japanese kanji for “rest” appears to be a combination of two others: the symbol for “person” and the one for “tree.”