The Maui documentarian discusses the transportive energies present in his images of Hawai‘i.

There is a disarming clarity in the work of Brendan George Ko. Familiar images — leaves, landscapes, faces — are rendered with miraculous lucidity. The living earth takes on a fluorescent glow. His photographs, effusive and otherworldly, pulsate with a tangible breath, one that implores us to listen closely for the stories that belie them.

The lesson that I had initially gathered from Ko’s work — much of which is gathered in his digital scrapbooks released intermittently over the years — was that technical polish, far from a mechanical interpretation of reality, can be a deeply expressionistic mode of picture-taking. What Ko asks through his work, however, is not specific to photography, and is far beyond a question of formalism: How may images reveal the spiritual essence within all living beings?

From the journals of his journeys on the road and his attentive documents of flora and fauna to his record of the Hōkūle‘a expedition, Ko illustrates the magnitude of the quiet, invisible life-force that undergirds the world around us.

“Portrait of a Mother II”

“Guava”

Vincent Bercasio One thing I admire about your photos is how digital they are. I’ve grown up with the idea that celluloid was supposedly the “organic” medium, which was often held in opposition to the sterility of digital images. In your photos, sharpness, clarity, and vibrance are rendered with an almost unreal polish, but they never compromise the humanity of your subjects. They imbue a different, almost spiritual quality — particularly in your photos of nature, with colors that aren’t quite true-to-life.

Brendan George Ko I am not trying to capture something photographic, I’m trying to bring about feeling and invoke spirits contained within my images. When I look at my images I want to be taken back to a time and place, feel the spirits of that moment, and I find how I capture and later handle my color and exposure is a key part of that summoning.

I don’t follow any standard of how something should look because truth be told, photography is a very colonized medium. I am doing my own flavor of it, followed by my na‘au, and truly feeling it out. The “digital” look comes from my high standards in the medium, coming from the color darkroom, and being very technically proficient, I know how good film can look, how sharp and colorful it can be, which borrows more from a commercial practice than hobbyist.

VB I’ve noticed your forays into video work, which, in the commercial realm, are often denoted as “motion assets” and other corporate neologisms. They often imply video is an addendum to or an extension of the images, rather than an art form in its own right.

BGK I come from a film background, I was studying cinema before I moved into a BFA in photography. My practice today, though I am known as photographer, I see myself as a documentarian who sees life and stories and figured out what medium to use to capture it. There are things that speak well as frozen moments and there are things that simply need to be in motion. When I was doing my MFA, my practice shifted into visual strategies: working with a story and figuring out what mediums work best to express the narrative, whether that be text, stills, motion, sound, object, or an ensemble of different mediums.

VB We’ve talked before about your interest in films, writing, and creating mixes. How do these other mediums influence your image-making, if at all?

BGK I love films, I love it more than any other art form. It incorporates music, photography, sound design, text, time, and performance into one coherent medium. When I was first establishing my practice, I often borrowed from cinema. It is a visual language that beautifully embeds narrative into images, and I can’t think of a medium that does it better.

“Tako Time”

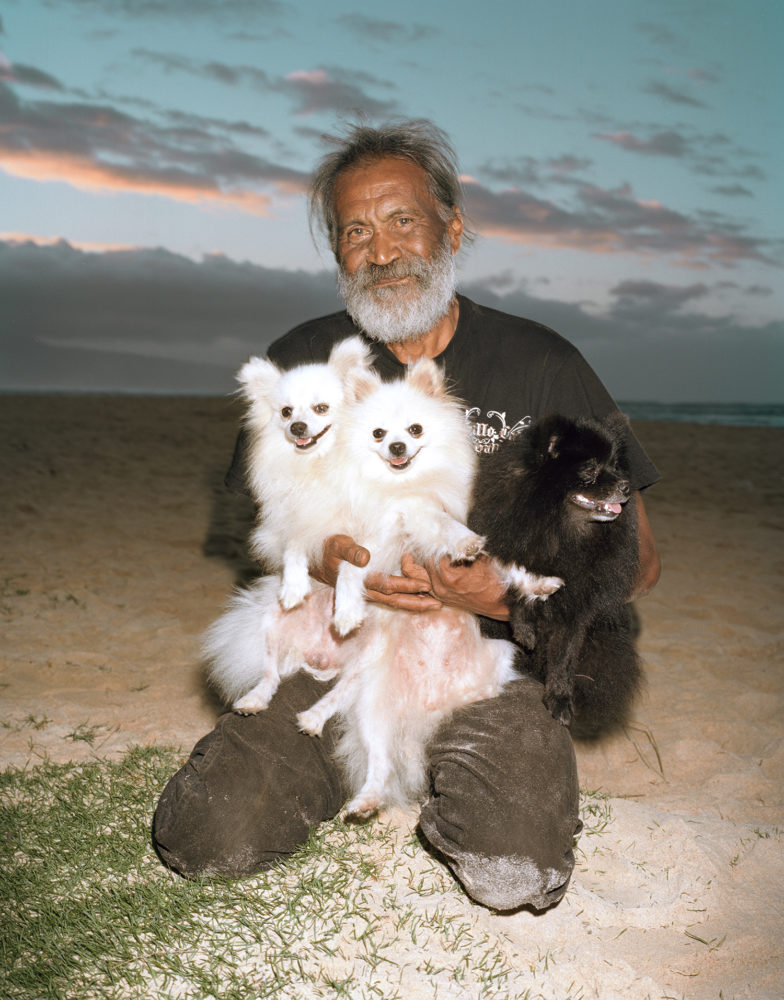

“Jamie and His Poms”

VB What do you see your role as when photographing subjects like the Hōkūleʻa and other cultural practices?

BGK My role on the wa‘a is both as a documentarian and as a perpetuator. When I first got into traditional voyaging there were all these documents available of the pioneer days that were painstakingly made to preserve a movement in time. I think of the likes of Ed Greevy documenting crucial moments of the Hawaiian Renaissance — we can hear the stories from the aunties and uncles, but to also see into the past is a critical placeholder to not having lived it. You can see spirits, captured energy, and feel something deep within that work wonderfully in tandem to oral tradition. I see my role on wa‘a as someone who is capturing today so that someone years later will be able to revisit the past with reverence. As a perpetuator, I feel a responsibility to help facilitate cultural practices, and aid in education and public awareness, which has become my secondary role in the community.

VB I find a dialogue in your work, between the typical images of Hawai‘i — often overprocessed, garish, and in service of selling a paradisiacal, false vision of the ‘āina — and yours, which smartly subvert that formula using similar techniques to radically different ends.

BGK I have always felt strongly adverse to how Hawai‘i nei is framed from the outside. It is often presented as this impossible paradise, uncomplicated by colonization and illegal occupation, where brown skin and the textures of Polynesia are exoticized as objects rather than living things with their own narratives.

I feel a responsibility to portray Hawai‘i nei in a more truthful matter, speaking honestly, and sharing both the beauty and tragedy that this place holds.

Brendan George Ko

A while back I was approached by Vogue where their editorial team asked me if I had any stories I was working on in Hawai‘i. I gave them the story of a Hawaiian voyaging canoe that traveled the world for four years and was coming back home. It was a story I had been spent many years researching and volunteering within the community. When it was published the story credit was taken from me, given to the editor, and I didn’t make an argument against the editorial team because I didn’t own the story — no one did, and I had done something I hadn’t seen in Vogue ever, a story about Hawai‘i and about Hawaiians practicing their culture on their own terms.

VB Does your upbringing in Maui play a role in the way you approach images?

BGK Maui is home, it’s the only place I have ever called that. My folks are immigrants. My mother is from Ireland, my father from South China, and they immigrated to Canada, had kids and moved those kids to New Mexico, then Texas before settling on Maui. In New Mexico I was exposed to the Native perspective there of seeing the landscape filled with spirits and stories, and it is where I became an artist. Coming to Maui in 2004, I started to see a lot of parallels between my formative years in New Mexico, and those perspectives I started to learn grew more deeply here as I learned from the Kānaka ‘Ōiwi community.

“Red Albizia”

“Makoa at Kealia”

VB What does it mean to you to be a photographer of Hawai‘i?

BGK Kuleana to this place, its spirits and its people. I find myself on a lot of projects led by agencies and organizations from the mainland that know very little about Hawai‘i’s politics, history, and culture. I feel a responsibility to portray Hawai‘i nei in a more truthful matter, speaking honestly, and sharing both the beauty and tragedy that this place holds.