In manuscripts and photographs, Hawai‘i’s historical record at the Hawai‘i State Archives is rich with untapped ‘ike. A kanaka street scholar reflects on its magnitude.

E heluhelu i ka ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi (Read in Hawaiian)

In 1862, prolific Hawaiian writer Joseph Ho‘ona‘auao Kānepuʻu saw a fragmentation of a chant in the moʻolelo of Hiʻiakaikapoliopele published in Ka Hoku o ka Pakipika. Concerned, he wrote in to Kapihenui, the newspaper’s editor, on the October 30 issue: “E makemake ana ka hanauna Hawaii o na la A.D. 1870, a me A.D. 1880, a me A.D. 1890, a me A.D. 1990.” (Translation: “Generations of Hawaiians in 1870, 1880, 1890, and 1990 are going to want [these moʻolelo and mele].”)

This excerpt, dusted off and translated by Noenoe K. Silva in her book The Power of the Steel-tipped Pen, reminds us that our kūpuna chanted in the rising sun with the same fervor that their voices reverberate in our archival materials, ensuring that if the sun rises, our people will too.

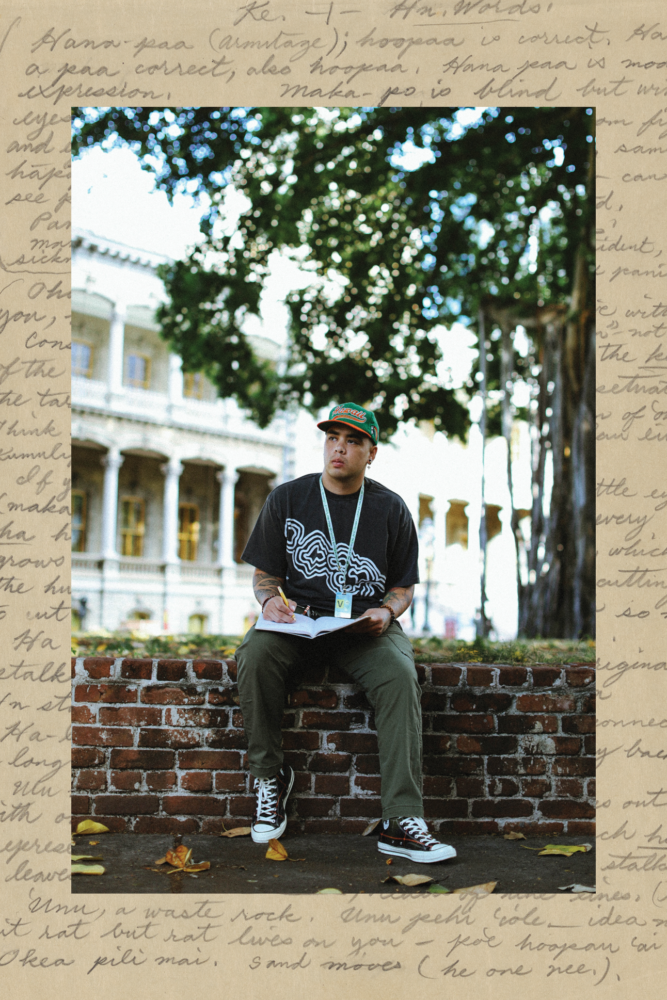

As the sun’s rays warm ʻIolani Palace from behind Mānoa, a few of us are nestling into the cold of the Hawaiʻi State Archives, jacketed and warming ourselves and spirits for the day ahead with coffee, māmaki tea, and laughter.

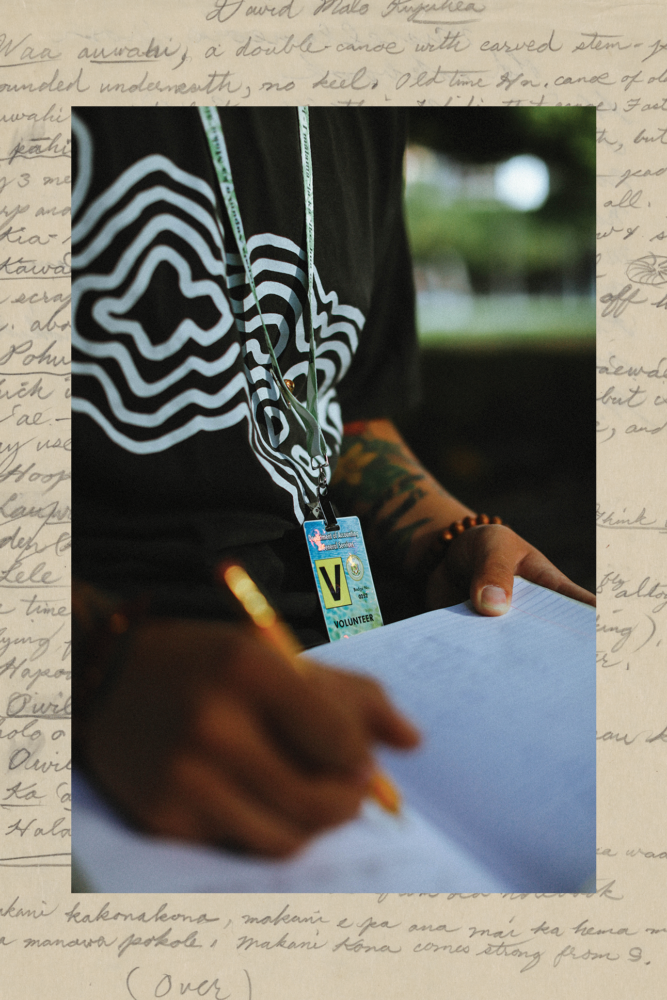

Then we part ways, heading toward our isolated rooms. Some of the archivists go upstairs to search for records, some prepare the digitization station, and a few of us head to our translation spaces. As a graduate research assistant for the archives and “honorary archivist,” a title appointed to me by the Hawaiʻi State Archives, I tirelessly bounce between all of these capacities.

Our kūpuna chanted in the rising sun with the same fervor that their voices reverberate in our archival materials, ensuring that if the sun rises, our people will too.

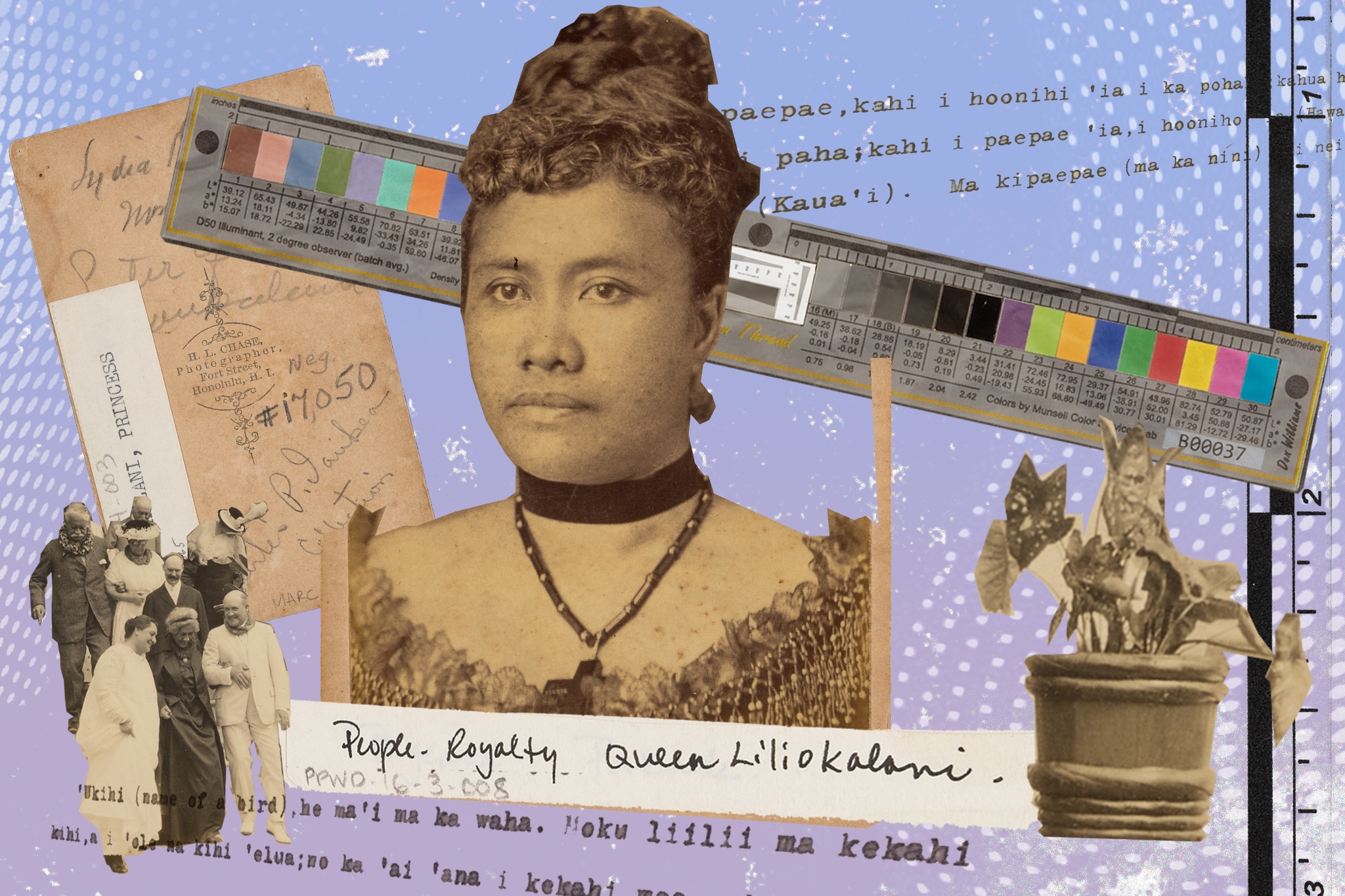

About a decade ago, I was a troubled undergraduate student at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa when activist and professor Lilikalā Kameʻeleihiwa tasked me and better prepared scholars in her Hawaiian Genealogies class with visiting archives. On the 20-minute ride from UH to the State Archives aboard the A bus, I prepared myself with paʻi ʻai, ʻawa candy, pule, and bumping Aquemini by Outkast. When I arrived, a small crowd of students were already slowly finding their ways inside. I followed them into a hidden elevator and headed upstairs to see a daguerreotype of Lydia Pākī who later becomes Liliʻuokalani and we stepped into the mana of our intellectual cosmogony.

There exists a dichotomy of jovial and tragic moments in Hawaiʻi, and at the Hawaiʻi State Archives, there are 400,000 such moments intimately documented and crying out to be dusted off at the Hawaiʻi State Archives. These documents—material ancestors in a multiplicity of languages—are elders holding knowledge like tattoos across wrinkled, dainty bodies. Through the archives’ sterile walls wafts a fragrance of an ancestral past, inundating a revolution of consciousness, enticing us. Our ancestors carry this fragrance like rustling leaves whose veins are inked with cursive, wanting to hold, caress, pray for, and provide refuge for us all.

Such ancestors are accessible to the public by way of short encounters with rascals behind the archives’ counters who enjoy baked manapua, poi malasadas, and deep talks about spirituality. Occasionally I will hear researchers crying with joy after seeing a photographic emulsion of their ancestor for the first time or holding a document that an ancestor signed. If you are here long enough, you’ll likely also hear grunting and grumbling about the people who conspired to overthrow Mōʻī Liliʻuokalani on January 17, 1893.

You have probably asked, though, what is archival research good for? Archives, like trees, store information and communicate through root systems across generations. The Hawaiʻi State Archives houses the minutiae of ancestral pasts and futures, the good and bad, at moments which needed instantaneous documentation. There are various types of materials and collections. My personal favorites are the manuscript collections, which provide running dictionaries of chanters, different versions of moʻolelo, recipes for ‘ōkolehao, drafts of mele, personal newspaper clippings, and photographs. There are photographic collections of glassplate negatives that remember ancestors both human and non. The Governmental Collections house petitions, the draftings of funeral processions for various aliʻi, menus for evening parties of our reigning monarchs, an account of the 400 pounds of poi per week that was consumed within the Palace walls, the nightly watch minutes for ʻIolani Palace, and the amount of coffee the night watchmen drank on a typical evening. There are even maps colored by place names and names dusted away in chants.

Archives help us remember the songs composed for the Wilcox Rebellion which recollected the way the land protected the restorationists-turned-political prisoners. They help us recollect that while some brilliant men attempted to create the first draft of the Kūʻē Petitions against annexation, it was the more brilliant women who revised, crossed off, and corrected the petitions, then organized to get more than 20,000 signatures from children, women, and men from all across Hawaiʻi to sign. We now know, because of archived letters sent home from her Royal Majesty the Queen Liliʻuokalani while seeking restoration abroad in Washington D.C. in the tumultuous aftermath of the Overthrow, that she provided money to ensure that the children of multiple schools across Hawaiʻi were well fed.

These documents—material ancestors in a multiplicity of languages—are elders holding knowledge like tattoos across wrinkled, dainty bodies.

Archives ensure our relationships outlive us and ardently make refuge for the future. As the Holoʻuhā breezes across the knees of Kaʻau Crater and Pālolo, it becomes a memory of keiki sitting on their parents’ lap during late evenings games played by Aʻa Mākālei, the Hawaiian Language Softball Team, in the 1990s. The Ua Līlīlehua drifting softly down the cheeks of the valley reminds me of Uncle Keala Kawaahau, who taught me how to write my first rap in ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi as a student at Ke Kula Kaiapuni ʻo Ānuenue. Here, the Pāʻūpili rain glides off rooftops with the warmth of an aunty whose dress, stained by sour poi and warm squid lūʻau, does as she glides across a room. This crater, where we mix ʻawa for our lāhui at Da Muliwai on Māhealani moons, is simultaneously old and new. These moments reactivate moʻolelo to remind us that archival research weaponizes our stories with knowledge of our past for a better future. To know, diligently, that prior to American Occupation, life in Hawaiʻi was superior. It is no longer an abstract thought—there is documented proof. Archives free us from the shackles of a colonized mind.