Beneath the sweet strings and harmonies of modern Hawaiian music lie complex compositions that are laced with hidden messages and political sway.

On a Sunday in June, I took a drive out to O‘ahu’s North Shore. As I passed Dole Plantation, radio static started to consume the airwaves, until just two stations were left—HPR’s “Kanikapila Sunday” show and KTUH’s “Kīpuka Leo.” While I appreciated the beautiful Hawaiian melodies coming through the speakers, as a non-Hawaiian speaker, I failed to grasp most of the lyrics. I flipped between the stations, trying to isolate words, and then I noticed a brief phrase repeated again and again: “ka puana.” As I listened closer, I found it appeared in almost every Hawaiian song.

“Puana,” I learned, is the summary refrain, theme, or beginning of a song. To sing the word is to call for a return to that note or line, or to simply begin. This gesture reminded me of learning dances for May Day in elementary, the kumu calling out moves ahead of the song’s next lines. “OK, now do the ‘ami!” she would say, and we would rotate our little hips to the next line.

I sought out an expert to confirm my hunch—that “ka puana” was linked to hula—and was connected with Hawaiian musician and educator Aaron Salā. He explained the recurrence of “ka puana” indeed goes back to a performance style called hula kuʻi, which came into existence after Western contact and uses postcontact elements like the Western diatonic scale and modern stringed instruments. Salā said, “The last verse of a hula kuʻi song, regardless of the length of the song itself, is signaled by the haʻina,” a call to sing the song’s puana.

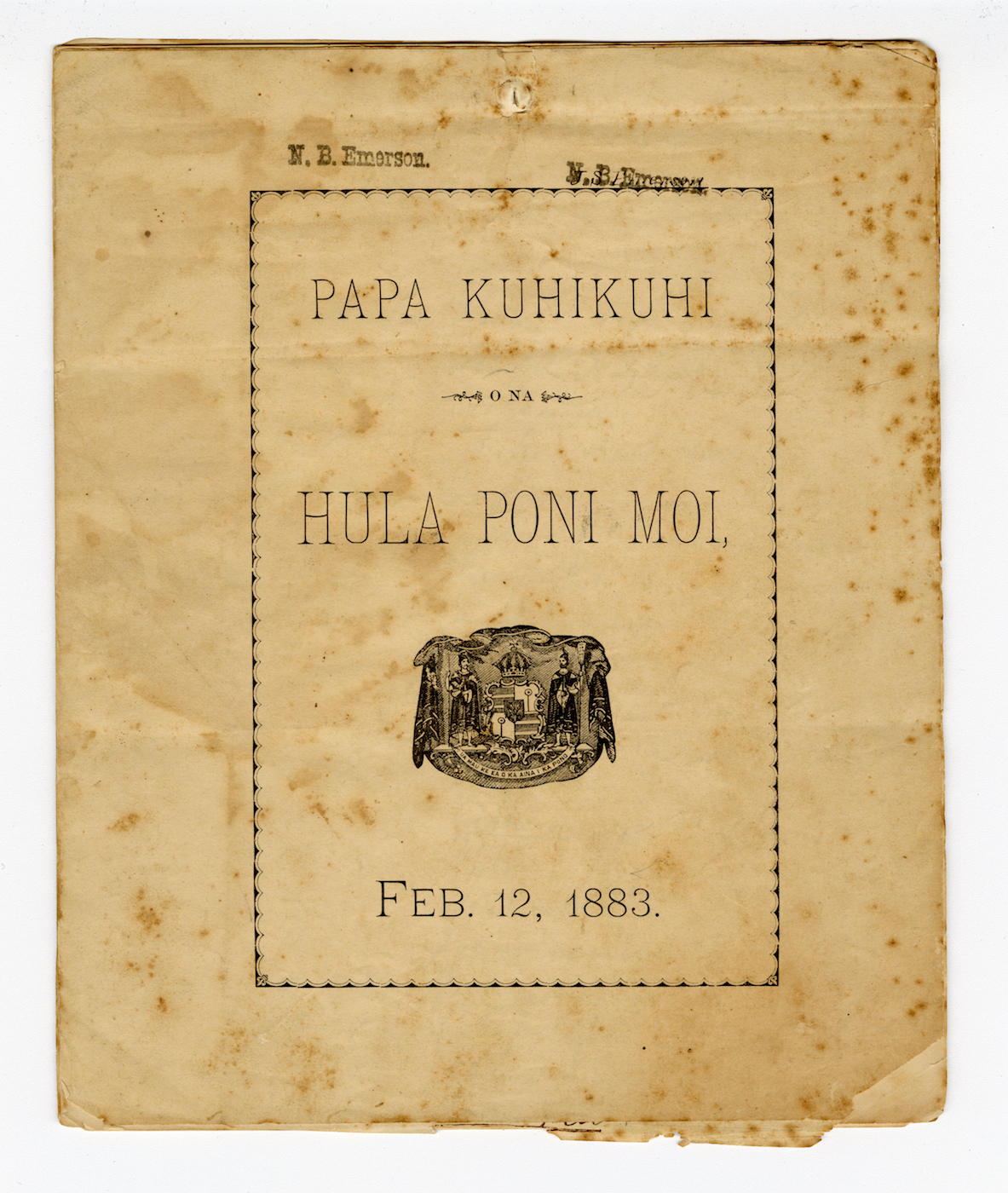

In her book, Aloha Betrayed, Hawaiian scholar Noenoe Silva states that hula kuʻi goes back to February 1883, when King Kalākaua held his month-long coronation ceremony, which was eight years overdue. To properly celebrate, Kalākaua, known as the Merrie Monarch, ordered the printing of Papa Kuhikuhi o Na Hula Poni Moi—a program of oli, mele, and hula—to be distributed ahead of the event. The schedule included hula ma‘i performances, an older style of dance often associated with procreation, as well as the formal debut of hula kuʻi, which was, according to Hawaiian music scholar Amy Stillman, “a vehicle for reinforcing Hawaiian pride and being Hawaiian and also for validating Kalākaua’s right to rule.”

However, the promotion of such hula seemed risky to The Hawaiian Gazette, a haole-owned newspaper, which predicted that “the law of the land may be broken.” The law in question was a carryover from the 1830 ban on hula urged by puritanical American missionaries. “[Their descendants] denounced the program as obscene, as well as illegal under the statute against public nuisances,” Silva writes. These self-appointed censors were especially bothered by the inclusion of hula ma‘i. Lawyer and legislator William R. Castle went so far as to have the document’s printers arrested.

But with Kalākaua’s defiant blessing, the program proceeded. The event reinvigorated hula and mele production, as well as the use of kaona, or hidden meanings, which abound in hula kuʻi compositions. The kaona tradition is thriving in the music of modern haku mele (composers), like performer Chad Takatsugi and lyricist Kahikina de Silva, who collaborated on the song “He Wehi No Pauahi,” which won the 2016 Nā Hōkū Hanohano Haku Mele Award.

The mele honors Hawaiian princess Bernice Pauahi Bishop and demonstrates how kaona can be reinforced by the puana. In the penultimate verse, de Silva alludes to the tradition of bringing roses to Pauahi’s tomb on her birthday, and then declares her as “a queen in my eyes / working for the pono of our lāhui.” This kaona-rich line can mean “the good of our people” and “the right of our nation.” This leads into the puana, which enshrines Pauahi as a lei of roses. Like a lei-maker looping the thread back through the same flower, de Silva repeats the image of the rose to strengthen the impact of the lines between them, and the kaona they confer—a lamentation for a queen that never was, and an assertion of the royal’s lasting power.

Wordplay like this is a given for Takatsugi. “In one moment, you could hear a composition of a dew-kissed lehua blossom representing the composer’s loved one, and the next moment you could hear about the steamships going between the islands, and in yet another moment you could hear about political turmoil at the turn of the century,” he explains. “It was a common practice to use the imagery of a storm to represent political turmoil, or to refer to people as ‘pua kaulana aʻo Hawaiʻi,’ or ‘proud flowers of Hawaiʻi.’”

Such is the case in the popular song “Kaulana Nā Pua,” written by Eleanor Kekoaohiwaikalani Wright Prendergast, a late-19th-century haku mele for the Royal Hawaiian Band. But few non-Hawaiian speakers realize that the hula kuʻi-style song, written in 1893, was a thinly veiled protest of Queen Liliʻuokalani’s overthrow. In translation, Prendergast tells of the flowers of Hawai‘i famous for their loyalty when “wicked delegates come with documents to cheat them.” The song offers overt support for Liliʻuokalani and ends, “Haʻina ʻia mai ana ka puana / Ka poʻe i aloha i ka ʻāina.” Translation: “Tell the story / Of the people who love their land.” Neatly ordered into strophic four-line verses and a choral refrain—the puana—these messages of hope and solidarity, unbeknownst to the oppressors, rode across the airwaves of the new Republic as if within a Trojan horse.

“Some of the most poignant and profound compositions have six to eight words in an entire verse,” Takatsugi says. “Someone who is listening with context and intent will hear the volumes of sublevel text that those six to eight words carry with them.” This understanding can start with a single word, which, like a single flower in a lei, loops you into a blossoming continuum—playing every Sunday, when all the rest is static.