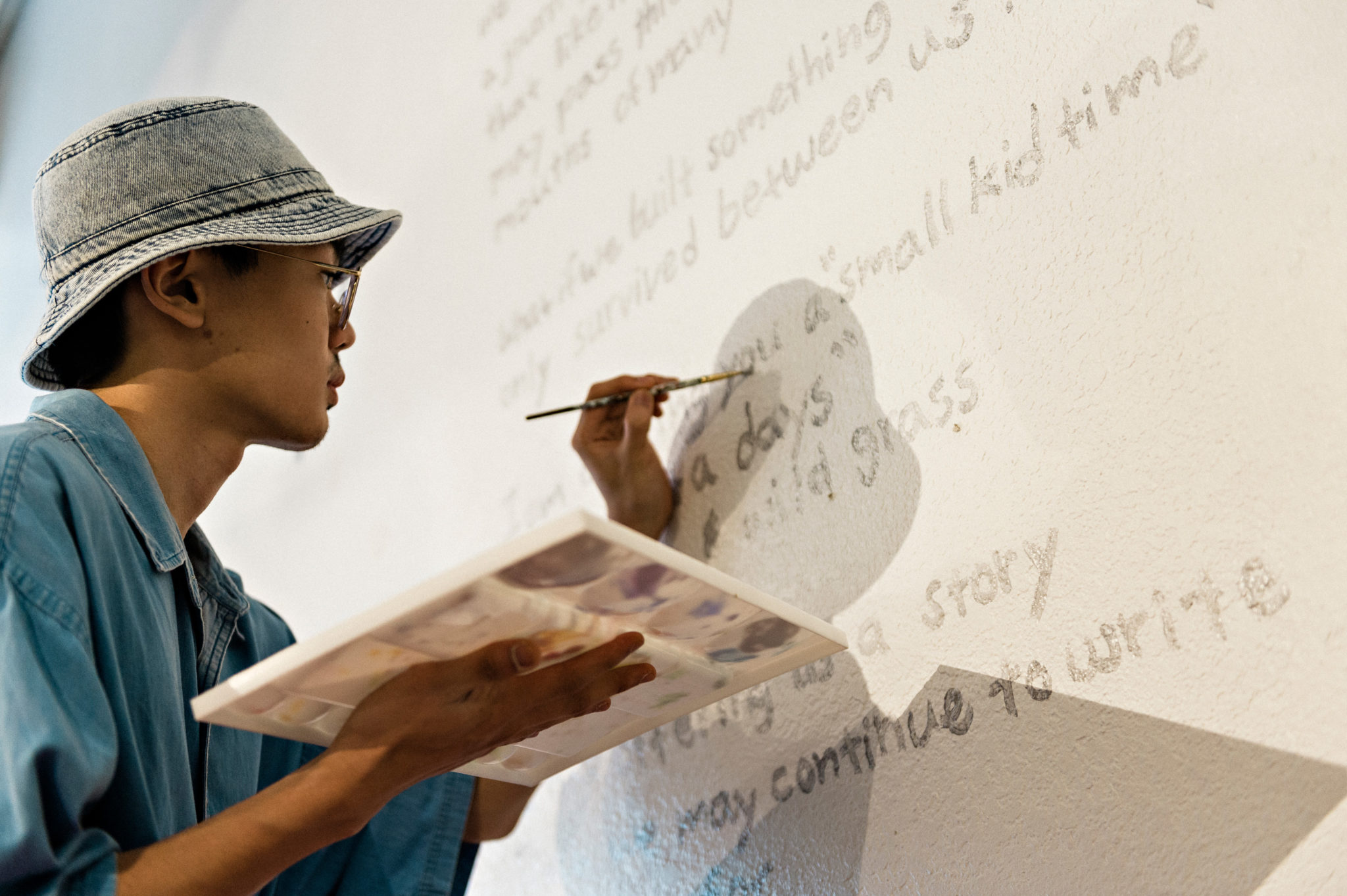

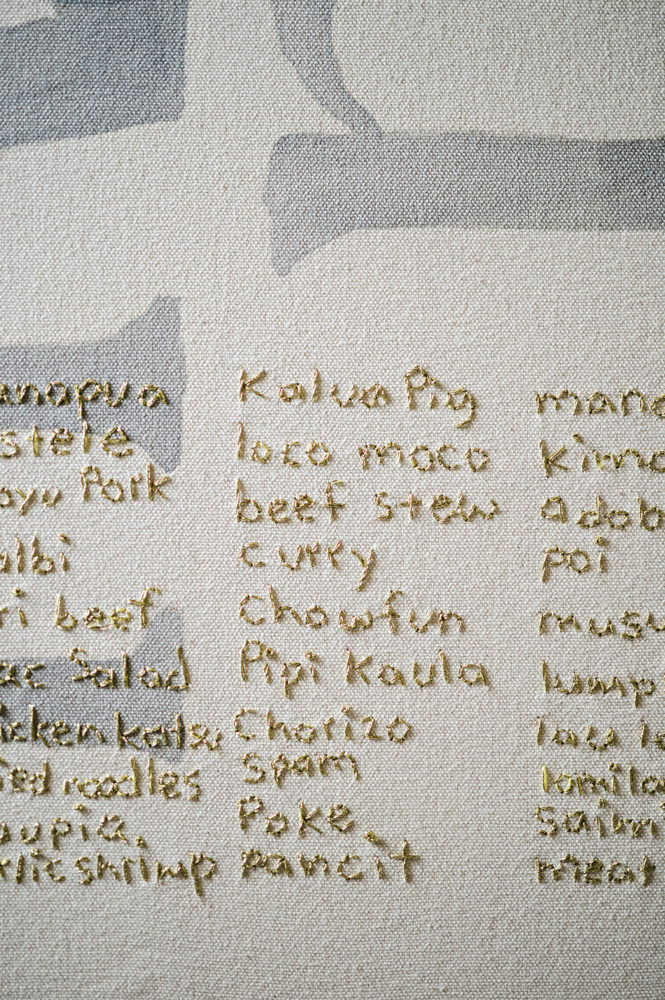

In his 2021 gallery shows, Mukashi Mukashi and Talk Story, artist and viral TikTok creator Dane Nakama presents a love letter to local culture and a sly critique of Hawai‘i’s blunt realities.

“I would say this room is best viewed with your shoes off,” says artist Dane Nakama before leading me into a gallery carpeted with AstroTurf. “The grass costs plenty money that’s why.”

Going barefoot is just one of the many sly references to local culture in Mukashi Mukashi, Nakama’s first gallery show in Hawai‘i, showing at The Gallery at Hawaii Theatre through the end of April 2021. Its presiding ethos? If you know, you know.

In one piece, jalousies open into a painting of a rainy blue sky, a green clay gecko perched playfully on the window frame. In another, the word “paradise” is painted upside down with li hing mui. He equates the flavor of the dried Chinese plum with growing up in Hawai‘i.

“When you first eat it, it’s not the most satisfying or easy to get acquainted with because it’s sweet, salty, and sour,” says Nakama, a 21-year-old senior at the California Institute of the Arts. “But that’s the experience of living in paradise.”

Last March, over spring break, Nakama flew to Hawai‘i with the intention of doing research for his senior project, an art show focusing on local Pidgin and the history of immigrants to Hawai‘i’s sugarcane plantations as it relates to his Japanese-Uchinanchu ancestry. Then the pandemic hit.

“I was like, wow, I guess I’m going to do my research for a really long time,” says Nakama, who grew up in Pearl City. Forced to move home, he turned to TikTok to connect, posting missives as @umeboi_ on everything from Asian settler colonialism in Hawai‘i to process videos of his art. Most prominent are his TikTok videos explaining art history, which reveal Nakama’s knack for translating art jargon into language both conversational and informative. (One post on the work of Swedish artist and mystic Hilma af Klint has been viewed 1.2 million times).

Following in the footsteps of his parents—his mom is a third-grade teacher and his dad teaches seventh-grade history—Nakama wants to teach one day.

“I know it’s probably biased,” he says, “but I honestly think teachers are one of the most influential occupations you can have.”

A week after the show’s opening, sitting barefoot on the artificial grass surrounded by his art, I spoke to Nakama about Mukashi Mukashi, accessibility in the art world, and myths. Nakama’s most recent show, Talk Story, is currently on view at Fishcake, a showroom and gallery space in Kaka‘ako.

You’ve been home unexpectedly for over a year now. How does it feel?

Being home was kind of a really exciting experience actually, because this is the first body of work I made about being from Hawai‘i. I’ve never addressed that topic before.

Was something holding you back?

I thought being Japanese-Uchinanchu from Hawai‘i was so specific of a narrative that nobody in my school would care or be interested in it, which was ignorance on my part. But it was also partly that, as I was making this work, I didn’t have the vocabulary, visually and literally, to talk about it with myself—negotiating that type of upbringing-slash-identity.

And so objects in this show are co-made or were made long ago by my grandfather or passed down by my great-grandfather. I really wanted to bring as many people with me to this show. Maya Angelou said it whenever she gave a talk: she brings everyone from her life, her past, with her. That really resonated, especially with a show like this.

There’s a sense of whimsy throughout Mukashi Mukashi, including strains of folklore interpreted through the lens of Hawai‘i. Like this piece depicting Momotaro-san in the sugarcane fields. What role do myths play in your work?

I like the term “mukashi mukashi” because it can both mean “once upon a time” and “a long time ago.”

With that comes a sense of reality rather than strictly myth based or fiction—more of a fantasy-inspired view of reality. But I do think that this approach to storytelling has allowed me to confront myths of my own identity. Both in a sense of acknowledging the blunt realities of Hawai‘i, be it the dismantling of the coloristic image of paradise enforced and profited from in Hawai‘i, to the honest appreciations of little moments, like interacting with banana trees when I go on walks.

I think I tried to use the tool of a fairytale—or rather, reconstructing a fairytale—to frame my own relationship to Hawai‘i as one that isn’t over-romanticized but still allows me to appreciate aspects I’ve previously taken for granted.

This approach to storytelling has allowed me to confront myths of my own identity.

Dane Nakama

In an alternate reality, Mukashi Mukashi would be showing in California as your senior project. What does it mean for you to be showing it here in Hawai‘i instead?

Beforehand, I didn’t know when my family would ever get to see my work. I had my first art shows in Japan and California before I even had one in Hawai‘i, which is very telling as far as my family knowing what I do.

So I was very much like, this is the moment. I had my grandmas come, my 100-year-old auntie was able to make it, people that I didn’t at all take for granted. Like if I’m going to show this, I’m going to make sure that it’s a show that they can appreciate. It was stepping out of my comfort zone because in the art world, we have a tendency to cater towards only art-world people, and as much as we don’t want to admit it, it’s very much this bubble.

And so me having to reconsider and be like, OK, how am I gonna frame the show so that my family can understand it while also spearheading the ideas that I want to get at in my work? I’m not going to compromise for either side, but how can I meet them in the middle?

So making the show more accessible in a way?

A bit. I mean, even previous to this show, a big aspect of my practice was accessibility. My big goal is to break down visual literacy and confront ideas that are equally rigorous as they are democratic.

Is that what made TikTok so exciting to you?

Yeah, I ultimately want to teach, so when that community [on TikTok] started to develop, it taught me so much about navigating that space—like every video was a test of what words I should or shouldn’t use, and in what matters I should explain something so it could be well received and people could walk away like, wow, I actually learned a lot. That totally reframed my approach to artmaking as well. If I talk like this in my videos and I’m satisfied, I shouldn’t hold myself back from making work that I just want to make, or [from making] failed attempts in my work as well. I was not at all anticipating that.

Many of your pieces incorporate two dots. Has that become your signature?

I’ve used them for about two years now—kind of going in the same line of, how do I make art both accessible and conceptual? I always tell people art is the relationship one develops with an artwork, and when I put two eyes on any object, I can tell people, Oh, it’s eyes. These objects are looking back at you, like imaginary friends. You’re more enticed to give it time and stare back at this thing. It’s also kind of cute—I think the two dots are the closest I’ve gotten to actually bridging the gap between cuteness and conceptualism. And cuteness as a means of disarming viewers is very effective.

I don’t know if I’ve ever sat on the floor of a gallery before. Why the fake grass?

I first used AstroTurf in a show at my house, for an open studio showing. A big part of it for me is to dismantle the white-gallery feeling. I love the art world, but I can understand that it’s a very sterile environment. It can be very intimidating and very professional. I want people to come into this space and feel like they can spend time.