E heluhelu i ka ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi (Read in Hawaiian)

With a rising interest in Hawaiian language, island media can foster broader havens for the native language to thrive outside of the home and classroom, writes a leader in the field. It’s only the beginning.

Images by Mahina Choy-Ellis

Edited by N. Ha‘alilio Solomon

English translation by Kimopō

Greetings, dear reader of the same mode of expression, my companion with whom I find rest in the shelter of the Hawaiian language.

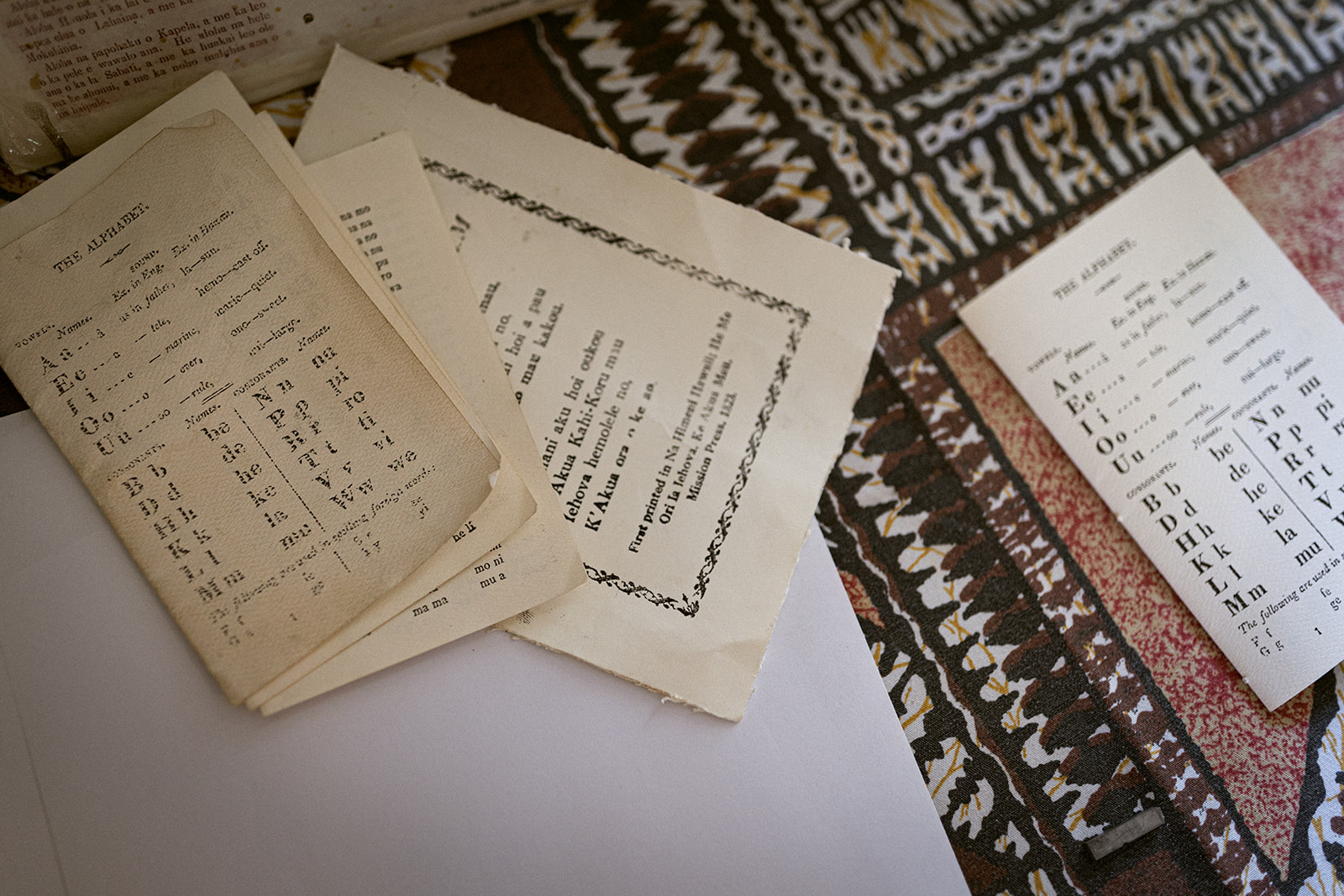

Your author has been asked, what is the role of Hawaiian-language media as a foundation, a support, or perhaps a nourishing hand in reviving the language of our ancestors here in the present time? As a product of the university, my thoughts turned quickly to the sage words already captured in various texts and pages that hold such wisdom. Noenoe Silva, for example, and her extension of Benedict Anderson’s concept of imagined community in her reference to the Hawaiian language newspapers as a venue in which Hawaiians actively participated in nation-building. And Leanne Hinton, who advises that the life of the language is in its pervasiveness in all aspects of human life, from the neighborhood to the courtroom, from commerce to the ball field, and in every channel of our abodes — newspapers, television, cinema, magazines, etc. And there are many other brilliant theorists out there as well.

However, during our time here in the delicate confines of this publication, I lay those voices to the side and pay heed to a different one. It is the voice of aloha, the voice of life, a voice that resonated in my ear just a few weeks ago. That voice belongs to ʻAnakala Eddie Kaanana. A native son of the lands famed for ʻōpelu fishing, of Miloliʻi. He was a man who would always turn his hands to the soil to learn the lessons and the life that the kalo provides for his people. He was also a native speaking elder beloved by those he raised, those who cherished him from Miloliʻi to the verdant valley of Pālolo. My meetings with this native of the land were few when compared to others’. The value of those meetings, however, is priceless, incomparably so. And here he is, still teaching this young one.

It is because of Hawaiian-language media that there is space for our havens to exist, as well as space wherein we can speak our language.

My thoughts go back to one such meeting in the year 2000. It was when ʻAnakala agreed to travel with the Hawaiʻi Delegation to the Pacific Festivals of the Arts, which was being held in Kanaky (New Caledonia). Then there was me, a member of this delegation through my mother’s hula school. Just prior to our departure from our home for those distant islands, ʻAnakala mentioned that perhaps we should all get to know each other and share the things that we would showcase abroad. So, we did. Dancers danced, singers sang, actors acted, and crafters showcased their crafts. As for ʻAnakala, he talked about fishing in the ways in which he was taught.

In the middle of his storytelling, he grabbed two small stones. One black and one white––it was coral. He must have seen the puzzled looks of the onlooking novices, because you could hear the excitement as he teasingly asked, “And? What are these stones for? Anyone know? Sheesh! Probably not! These are for attracting fish.” Floored! I thought only sticks were used to entrance fish, yet apparently the old folks used stones to fish! Here is what he showed us.

These two stones were used for fishing in tidepools. When one stone was submerged, the water would bubble and rise up, and the fish in the pool would gather to observe the event. At that point, one could catch them by hand or with a net. The tricky thing was as soon as the bubbles would stop, so, too, did the interest of the fish, at which point they would retreat, shortening the opportunity one had to catch them. That would happen when the black stone was used in rocky pools, and the white stone in sandy ones. However, according to ʻAnakala, should one submerge the light stone in a dark pool, the fish would not be as quick to hide. Due to the disparity between the stone and its surroundings, curiosity arose in the fish, attracted to hang around the stone. The same happened when the dark stone sank to the sandy bottom of the pool. Perhaps we can think about Hawaiian-language media in a similar way.

The writer Kahikina de Silva, Mānoa.

The editor N. Ha‘alilio Solomon, Honolulu.

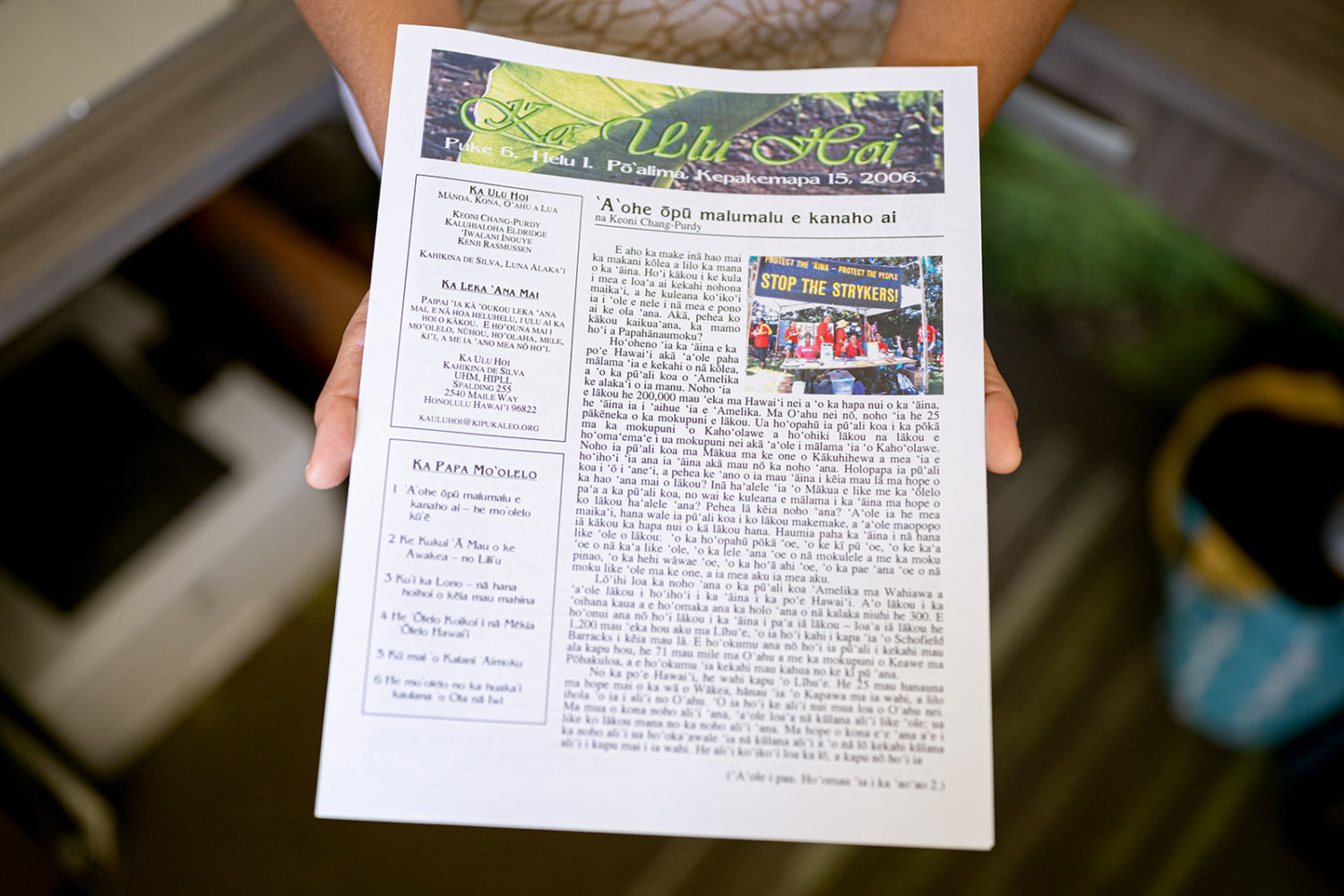

In this sort of tidepool, the Hawaiian language forms the bubbles that pique the initial interest to congregate, and the interest is indeed rising. It was at the theatre where us fishes schooled, in person for Nā Kau a Hiʻiaka, and virtually for He Leo Aloha. Every week, we gather among the inked words of Kauakūkalahale and the gentle voice of Ke Aolama to receive today’s news in the voice of our elders. Together, we tune into Kīpuka Leo to revel in the authentic sound of Hawaiian singing and conversation. And so on and so forth.

These efforts are incomparable in value, forming a pathway upon which Hawaiian language speakers of the home can meet up with those of the world. It is as if today’s Hawaiian way of life is a safe haven, especially for Hawaiian language speakers. The Hawaiian language may be fostered in our families’ homes, or in immersion schools and Hawaiian language classrooms, but when we leave these strongholds, auē! Our ears are struck by English, not long after which our mouths may follow. It is because of Hawaiian-language media that there is space for our havens to exist, as well as space wherein we can speak our language. Then, one day, the islands of Hawaiʻi will become a safeguard where Hawaiian language echoes on.

So, we have seen the importance for the Hawaiian language to be in all forms of media available today, as bubbles that attract the fish to gather. It seems, then, that the next question is, what kind of stone makes these bubbles? Is it the one that assimilates with its environment? Or perhaps, one that stands apart? The prosperity of the language and its people depends on standing apart.