Through historical records and nūpepa research, Kānaka voices reveal an archive of pilina.

Images by Chris Rohrer

Ua ala kue mai la na kanaka o Gasa.” Gazans Arose to the Fragrant Path

of Resistance.

A simple phrase, nestled in the naʻau of an article published on the final page of the June 17, 1892 issue of Ka Nupepa Kuokoa, interprets the story of Alexander the Great into ʻōlelo Hawai‘i. It may seem odd for Kō Hawaiʻi Pae ʻĀina, a nation constellated in the middle of the ocean, to be studying, translating, and then publishing the story of Alexander the Great during the late 19th century. However, Kānaka Maoli and writers in Hawaiian language archives were attuned to stories from around the world and our kupuna imprinted our genealogy in their public archive as a means to contest, contextualize, collaborate, radicalize, organize, and share ancestral stories while remaining active historians documenting the experiences of our own people.

In tumultuous times, especially around the time of the illegal overthrow, our kupuna turned to our own mo‘olelo for solutions while also reading stories of liberationist struggles from around the world. This archive of pilina bundles Kānaka Maoli genealogies of liberation to global genealogies of liberation like bundles of pili grass atop a house.

1839

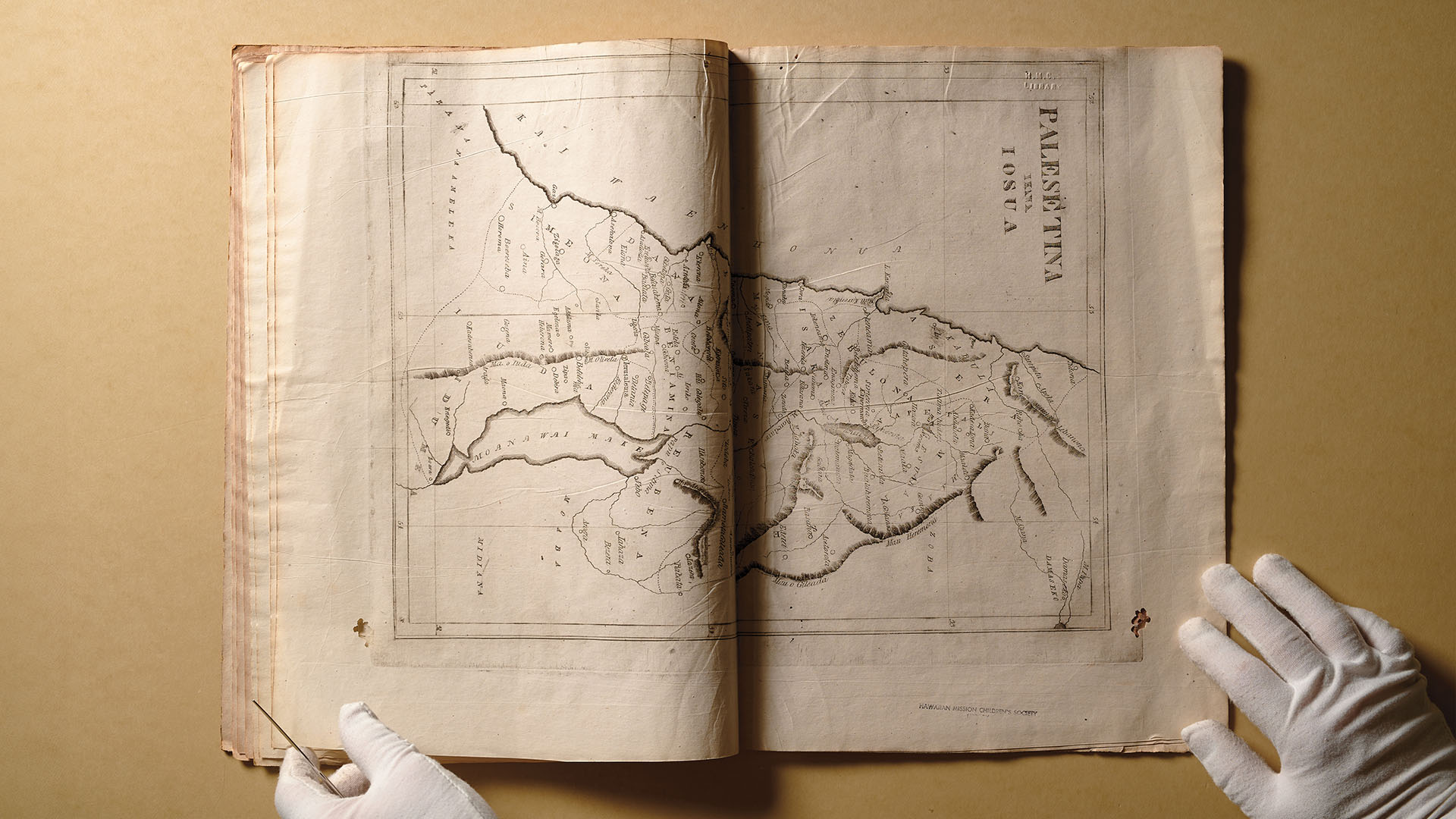

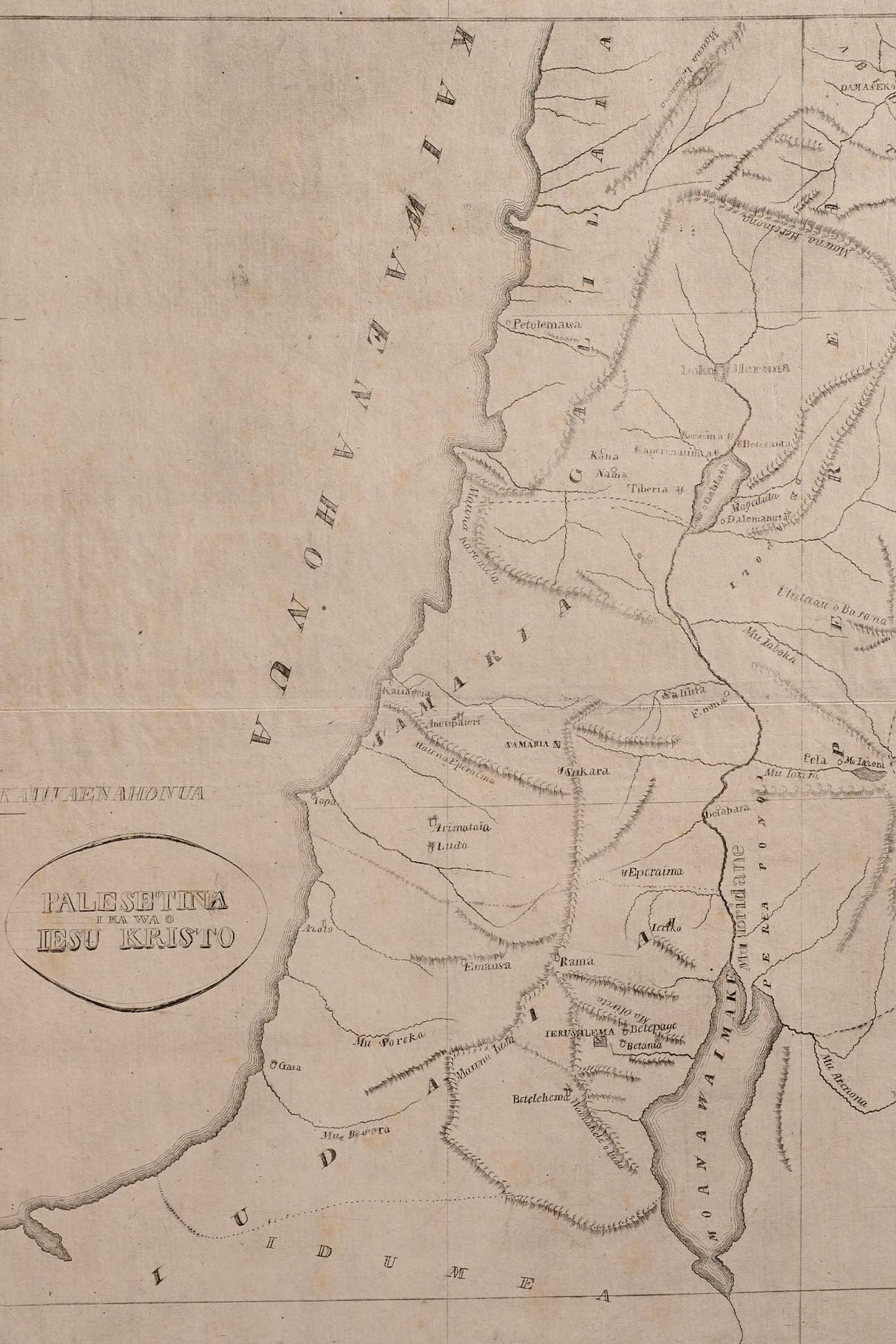

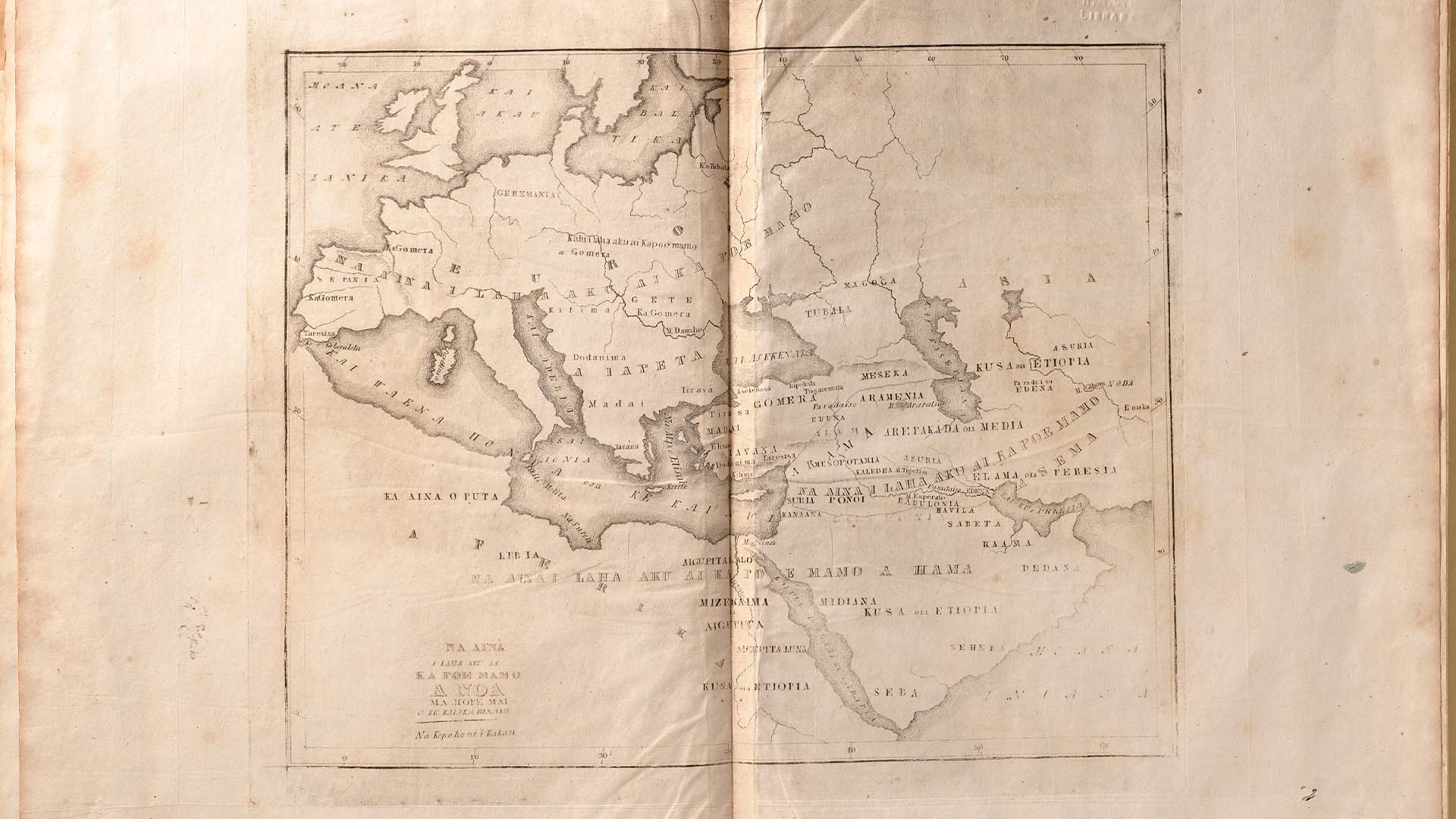

In ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi archives, stories about Palestine are evoked by names such as Palekekine, Palesetina, Palestina, Palestine, Gaza, Gasa, Ierusalema, and Tel Aviv, among other names. The introduction of new religion also introduced reading and writing to Hawai‘i, and from that, the name Palesetina to Hawaiʻi. A series of maps guarded by Hawaiian Mission Houses in Honolulu detailing Palesetina were primarily carved by a Kānaka Maoli cartographer named Kunui onto woodblock and imprinted onto large archival paper at Lahainaluna. Kunui’s carvings of Palesetina began in 1839 and ended in 1843, a year many Kānaka Maoli hold as significant because it was the first celebration of Lā Hoʻihoʻi Ea.

An assembly of articles mentioning Palesetina appear in nūpepa, Hawaiian language newspapers, from the time of the first publication in Hawai‘i in 1834 in Ka Lama Hawaii until the late issues Ka Hoku Hawaii in 1948, which was the last nūpepa in circulation for a stint of 30 years. Many of these stories are digitized and some are not, but all of them are protected in Hawai‘i archives. Just over a century of writing details the intimacy of daily life, draws connection between aliʻi and Palesetina, charts our connection to another, and is concluded by recollections of The Nakba. The Nakba, meaning “catastrophe” in Arabic, refers to the ethnic cleansing of Palestine and the near-total destruction of Palestinian society in 1948 through mass displacement and dispossession of Palestinians during the 1948 Arab-Israeli war. While the phrase Nakba is not interpreted into ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi, it is recounted in multiple articles of Ka Hoku Hawaii.

A constellation of genealogy and connection are offered over that century of literature surrounding Palesetina through nūpepa, links between their land, cultural practices, mourning practices, dance, song, and food. Of significance to Kānaka Maoli is an invitation by John L. Nailiili to compose new mele while offering mele that have been passed down in ʻohana. On October 21, 1845 in Ka Elele, Nailiili composed a kanikau for Timoteo Ha‘alilio, an aliʻi held in high regard who brought formal recognition to Hawai‘i as a sovereign nation-state by the West. This kanikau, or lamentation chant, also serves as a form of performance cartography, intimating site-specific and familial connections to the places associated with the person for whom it was composed. Traditional names for rains, suns, and famed locales throughout Hawai‘i are presented, followed by the sharing of a significant passage: “Aloha o Lilinoe ka wahine noho mauna / Aloha ka nahele o Opuola / Aloha na waipuna a me na kio wai o Palesetina,” interpreted as “Aloha to Lilinoe who resides and rules the mountain [Mauna a Wakea] / Aloha to the forest groves of Opuola [in Koolau, Maui] / Aloha to the multitudes of springs and pools of water of Palesetina.”

Other accounts published in Ka Nupepa Kuokoa, between March 31, 1866 and October 13, 1866, account for 19 installments of daily life in Palesetina to educate ko Hawai‘i Pae ‘Āina about the aina they’d been reading about for decades. Descriptions and translations of famed mountains, valleys, and rivers in Palesetina are so fertile that nupepa articles overflow with flowering descriptions of the lands that raise Palestinians. Some examples include mauna Karemela (Mount Carmel), Iapa (Jaffa), Awawa o Sarona (Valley of Sharon), muliwai o Kisona (Kishon River), and mauna Tabora (Mount Tabor). A favorite installment describes the abundance of laau oliva (olives trees), the way these olives grow, the heights the trees reach, and Mauna o Oliveta (Mount Olivet). Over two centuries later, the symbolism of the laau oliva resonates and echoes a haunting ancestral rhythm.

In Ke Aloha Aina, another favorite nupepa, many passages about Palesetina are published. Ke Aloha Aina’s original head editor was Iosepa Kahooluhi Nawahiokalaniopuu, sometimes referred to simply as Joseph Nawahi. At the time of Nawahi’s passing, Emma Aima Nawahi, his partner in aloha ‘āina, took over the nupepa and continued to print revolutionary thought. The Nawahi ohana was radical amongst Kānaka Maoli in the late 19th and early 20th century for being explicitly anti-colonialist and anti-imperialist through aloha ‘āina. This atikala highlights relationships between moolelo and place where multitudes gathered to incite change by having a deep relationship to the land. The highlighted portion below weaves in these sentiments in relation to Palesetina. Here is that passage followed by an interpretation: “oia hoi ka aina o Palesetina, oia ka aina o ka meli a me ka waiu, e kahe ana, he aina i piha i na mea e pomaikai ai na kanaka oia mau aina” interpreted to read “that is the land of Palesetina, the land where the honey and milk flow, abundant with blessings for Palestinians.” It can be used in a similar context to revolutionary Ghassan Kanafani who states, “The Palestinian cause is not a cause for Palestinians only, but a cause for every revolutionary, wherever he is, as a cause of the exploited and oppressed masses in our era.” Remembering, unearthing, and archiving these connections can sustain our ʻono for the milk and honey of liberation that will be the sweetest when they are from a Free Palesetina.

Kō Hawaiʻi Pae ʻĀina, a thriving constitutional monarchy in the 19th century, had aliʻi and makaʻāinana who engaged with nations all across the planet while remaining steadfast in defending our culture and home. This dynamic internationalism was intentionally orchestrated by Kānaka Maoli and is evidenced in innumerable articles in Hawaiian language newspapers which fasten our connection to each other while simultaneously critiquing colonialists and colonialism. Amongst the many nations that Hawaiʻi had developed a web of relationships with is Palesetina. Diplomacy between Hawaiʻi and Palesetina was forged through mutual recognition, respect, culture, and adoration for each other’s homeland, while Western diplomacy is a multigenerational beneficiary of systemic violence through dominance, extraction, and Western forms of sovereign recognition.—D. Kauwila Mahi

2024

The events that transpired on October 7, 2023 have garnered unprecedented attention for Palesetina. However, Hawaiʻi has a centuries-long connection to that beloved and storied land. Today, more than ever, we are unearthing connections as colonies experiencing displacement and occupation by imperial forces. We do not conflate the occupation of Hawaiʻi with the occupation of Palesetina; the violences inflicted by our colonizers are distinct. Hawaiʻi experiences slow violence through occupation: fuel bleeding into the veins of our aquifers, military occupation of sacred land, continued land dispossession, continued land desecration, mass exodus of our homeland, continued prostitution of our culture, missing and murdered Indigenous women, and the consistent threat of violence upon our land and people. Palesetina suffers the violences of occupation through land dispossession as well as continued land desecration; however, the genocidal campaigns of their occupier have erased whole genealogies from the earth in perpetuity, maimed and murdered women, children, and men, starved people who are seeking refuge, ethnic cleansing, made rubble of generational homes through bombs, turned ancestral food systems into ash, and destroyed their national archive. Put plainly, their colonizer is attempting to erase evidence of Palestinian existence. We have another commonality, our deep love and affection for our lands, so much so that we are committed to protecting her by any means necessary, which sometimes emerges as Aloha ʻĀina in Hawaiʻi and sometimes emerges as Intifada in Palesetina.

The world is different than it was centuries ago and we continue to fasten our relationship tighter to each other, especially in these dire times. We are bound by the same cause — the struggle for liberation. Our words do not serve as a comprehensive history of connection between Hawai‘i and Palesetina, rather, we ulana, interweaving both our histories into a liberated future woven as a fine mat in the present to hold ceremony for those willing jump off the cliff of the colonial paradigm and dive into oceans of anti-colonial consciousness. As we submerge in this ocean we have a kuleana to emerge. While we are rising to the surface, the moon will playfully tug upon the ocean, we swim nearer the surface through our privileged responsibility of political education. As we emerge, we breathe in a constellation of deep love and struggle.

We as Kānaka Maoli striving for ea, emergent sovereignty, cannot have a politic constrained exclusively to our island home. To think that we could ever achieve liberation in isolation is the product of a colonized paradigm. We refuse this loneliness and choose to be Aloha ʻĀina. An Aloha ʻĀina, a steadfast lover of land and protector of Hawai‘i, must also stand alongside other Indigenous peoples who love their homeland just as we do ours. This also means standing in solidarity with our Black kin who have been forcibly removed from their ancestral homelands. We are not only fighting for a decolonial world, but an anti-racist one as well. One that is intolerant of anti-Blackness and anti-indigeneity. A world that holds the possibility for folks to make and remake connections to place.

The archive of pilina that Kānaka Maoli and Palestinians have to one another remains steadfast. Despite our respective ongoing battles against colonialism, we continue to recognize and celebrate each other as indigenous peoples and fight for collective freedom. One of the strongest examples of this relationship can be witnessed through Palestinian solidarity. In July 2019, a Palestinian delegation showed up in support of Kānaka Maoli protesting the construction of the Thirty Meter Telescope on Maunakea. On the Ala Hulu Kūpuna where respected elders blocked the access road to the summit, the Palestinian flag was raised among other national flags in solidarity with Kānaka Maoli. In Palesetina, Palestinians showed support for Maunakea by holding up signs and creating a mural in support of our struggle expanding our archive of pilina. Despite suffering violent regimes because of their occupation, Palestinians fastened our solidarity with one another. This unwavering support under dire circumstances should compel us as Kānaka Maoli to reciprocate that aloha and commit to speaking out against genocide. As colonialism seeks to erase us, we add to our archive a history of resistance so that we will always remember that we have stood for one another.

The archive of pilina that Kānaka Maoli and Palestinians have to one another remains steadfast. Despite our respective ongoing battles against colonialism, we continue to recognize and celebrate each other as indigenous peoples and fight for collective freedom.

‘Ihilani Lasconia

Even within our educational institutions, Palesetina has been a topic of conversation for generations. University of Hawaiʻi professors such as the late kumu Haunani-Kay Trask, Ibrahim Aoude, Cynthia Franklin, Heoli Osorio, and Dean Saranillio have taught about the occupation of Palestine and its connection to movements for Hawaiian sovereignty. Outside of the academy, activists and organizers from Hawaiʻi have gone on exchanges to Palesetina through the Palestinian Youth Movement to strengthen our pilina and gain organizing strategies. Political organizations and activist groups such as Af3irm Hawaiʻi, Hawaiʻi for Palestine, and Women’s Voices Women Speak have been organizing around educating people about what is happening in Palestine and holding actions protesting Zionism and the atrocities carried out by the Israeli Occupying Forces.

Another organization in particular has been critical to re-strengthening the relationship between Hawai‘i and Palestinians. Created in 2013 by professor Cynthia Franklin, Students and Faculty for Justice in Palestine (SFJP@UH) is centered on fighting for a campus where the history of Palestine is able to be taught and discussed. Recently, SFJP@UH has called for the University of Hawaiʻi to divest from its ties to Israel. For years, SFJP@UH has brought out Palestinian artists, activists, and scholars to Hawai‘i to share their work with students, faculty, and community members. These exchanges include educational talks, art exhibitions, visiting historical sites, and sharing countless meals with one another. These events have been absolutely crucial to fortifying our archive of relation and strengthening solidarity between Hawai‘i and Palestinians.

All of these efforts are part of a mo‘okūʻauhau of consciousness that brings us closer together. Through education, resistance, and celebration we deepen and strengthen our commitment to one another as well as the ʻāina who raised us. Hawaiʻi continues to rise up against American imperialism in our homeland while standing with Palesetina. These moments of world-making carry us through the pain of living under occupation. There is deep joy and love in building this archive of resistance. It is because of this archive and longstanding memory that we have the ability to create opportunities to feel what it would be like to live freely, even just for a moment.—‘Ihilani Lasconia

Under the ever-impending doom and gloom created by imperialist forces, it can feel impossible to envision a reality not dominated by the West. For some, it is easier to imagine the end of the world due to climate catastrophe than to confront or contest colonization. One hallmark of capitalism, the system that created colonialism, is that it prevents us from dreaming and carving a way out of the current suppressive system. We are inscribing a k/new archive via photos on our phones as well as analog and digital cameras; enunciating poems on stages, in classrooms, in public; dropping banners as the settler-Amerikkkan government attempts to propagate and perpetuate the fallacy of their legitimacy; shifting consciousness through guerilla education in public; in street-art through graffiti and wheatpaste; through screen printed art on our clothing; and through Aloha ʻĀina music.

A series of pieces by street artist Tonk connects The Nakba of Palesetina in 1948 to Ke Kāhuli Aupuni, the Overthrow in 1893 of the Hawaiian Monarchy and Moʻīwahine Liliʻuokalani. These pieces are part of the public archive we are establishing which mark dissent for the colony and signals of affectionate-solidarity which unsettle the settler-state as well as the settler-within ourselves. We must prioritize pilina with those who are seeking an end to this cataclysmic structure. This relationship can be weaved by returning to and rebuilding an archive of pilina through solidarity. Everything was once k/new, remembering our pilina to one another before we experienced conquest is essential. We are extending the legacy of relations that our aliʻi and kūpuna left for us to maintain. Between Hawaiʻi and Palesetina, there are two centuries of pilina and we intend to make 1,000 more. Memorializing these generations of connection offers us a cultural foundation to stand upon — it is an ancestral wisdom. Nearly two centuries after the initial connection between Mauna a Wākea and Palesetina in nūpepa, our kupuna stood together once again. He wahi manaʻo kēia no nā mamo a ka ʻĪ, ka Mahi, me ka Palena. ʻAʻohe lua e like ai me ka ʻono a ka hani aʻo ka hulihia, we’d like to offer this knowledge to descendants of the ʻĪ, the Mahi, and the Palena clans. There is no honey sweeter than the taste of liberation. We must remember that there was a time before colonization and there will surely be a time after it.