MICROCOSMIC ORGANISMS: Little Worlds, Video Sculptures by Tony Oursler

“Artworks often speak in a foreign language, but they always try to tell us something about our own surroundings: they open up potential worlds that strangely resemble the ones we live in. Juxtapose one artwork with another, and you will have a miniaturized universe, a portable solar system- a refraction of the present, and a vector to the future.”

–Massimiliano Gioni, Your Now Is My Surroundings

There exists a kind of anxiety surrounding the act of referencing a culture that is still unfolding. In the fractured multiplicity that comprises the modern-day West, experience is suspended in a state of simultaneous repletion and deprivation; all of this, set against a backdrop of seemingly endless industrial and economic expansion. This is an existence of anhedonic longing that is often posited as the byproduct of hyperstimulation; think the rise of ephemeral internet memes, YouTube sensations, fifteen minutes of fame, a.k.a the next big thing. Considering this, the epoch of the late ’80s leading up to the present day provides a uniquely fascinating stage upon which to conceive and perceive contemporary art. Video art, it seems, assumes an especially important place on that stage, often dealing with reactionary concepts like narcissism, fear, and violence.

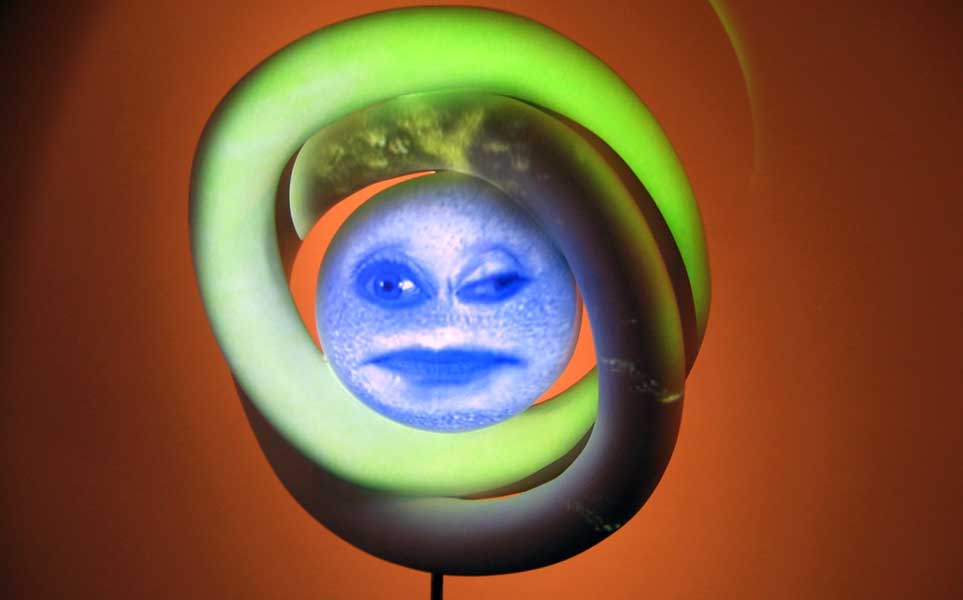

Such concepts are tackled head on in in the work of artist Tony Oursler, perhaps best known for his ground-breaking manipulation of various multimedia platforms. Little Worlds at the Honolulu Museum of Art stands as a mini-survey of his work going as far back as 1990. A selection of anthropomorphic “video sculptures” is represented from a 2007 collection, Anomalous Bodies, Resonant Dust and Worms, alongside a new body of work comprising of farcical, miniature worlds.

But what is really meant by uttering such descriptions? The question of how to accurately describe Oursler’s work is an arduous one. He is known for his use of video as a primary medium, yet his works often escape definitive categorization. With any given Oursler work, one can expect to find the projection of modified audiovisual components on to stationary surfaces (often constructed of fiberglass). This is the case with most of the pieces in Little Worlds. Many of the projections also depict monstrous and often comical visages; concerted constructs whose surreal facial features appear awkward and insubordinate in relation to one another. This inconspicuousness has much to do with transcendence; perhaps ultimately in Ourslerʻs mastery of the crossing of both material and conceptual boundaries that define what the art object can be. The parameters of such transgressions are apparent when comparing Oursler’s works to those of the relatively recent past. Take Bruce Nauman’s Bouncing in the Corner (1968) whose grainy, black and white aesthetic is the product of a self-operated VHS camcorder. Oursler’s meticulously calibrated, digital projections appear in contrast as the displaced “technological reliquaries” (to borrow from Paul Thek) of tomorrow.

Even having established such an objective, there remains a beckoning suspicion that there’s more to Oursler’s work than mere technological play. There is good reason for this. Oursler has emerged from a pool of artists whose works have come to encapsulate the attitude of postmodern society. Artists like Gillian Wearing, Matthew Barney, Cai Guo-Qiang, and Paul McCarthy (to name a few) have established various ways of exploring fantasy variations on origin and culture. These explorations reflect the frenetic and almost schizophrenic nature of modern consciousness, often embodying an uncanny mixture of diarism and the refusal of one’s origins. It is no mistake then, that Oursler makes manifold references to cosmic phenomena. Several pieces in the show bear titles that reference cosmogonic themes as a means to ontological rumination, such as I Like You Planet (2007) and Shame Phases Sun (2007).

Thanks in part to their audio components, the various pieces in Little Worlds function collectively, much like an interactive installation. In fact, upon entering the small gallery space, it is likely (however unwitting) that you have already acknowledged the exhibition as such. Co-existing in a single open space, the audio from one piece melds readily into that of the next, replicating the cacophonous murmur of mixed dialogue in a full crowd. Untethered Worms (2007), a fiberglass sculpture composed of side-winding cylindrical forms, is one of the pieces contributing to this dialogue. An androgynous voice can be heard speaking from the entangled mass of superimposed facial orifices: “Moments remain vague and free-form like storm clouds,” it recites in a slow and perplexed tone. “But deep inside my head, I have this horrible feeling.”

Across the room, Worms’ voices seem to echo in a strange exchange with those emanating from more recent pieces. Hierarchical Pastel (2012) is one of four small-scale constructions showing miniature people and objects engaging in nonsensical and sometimes futile actions. A small projected figure is seen twirling around in a seemingly endless display of physical exertion. Just a few inches below that, another crawls perpetually through a narrow corridor. Despite the initial astonishment of scale and detail (none of the projected figures stand more than a few centimeters tall), the actions that these dwarfed facsimiles carry out is what is truly substantial. Oursler has demonstrated a mastery of the use and manipulation of video as a medium, but to proclaim that’s all they are would be a mistake. In the presence of such Sisyphean imagery meant to provoke existential reflection, inquiries into the work’s technological construction or use-value appear insignificant.

Despite the doctoring-up of Oursler’s phantasmic images, what is achieved in reality is in fact the opposite of what one might expect. Through these projections, we are made to view the symptoms that have come to encompass our current epoch (schizophrenia and all) in an astonishingly clear light. Ruminations of this ilk forefront theories that position video as one the last forms of media capable of coming close to pure reflection. However subjected films may be to edits or jump-cuts, we are apt to come across instances in which they produce rough exposures of ingenuousness without the meddling of ideology . Here, a video camera frames the perfect picture of disinterested seeing; there are no exclusions of disfigurement (literal or metaphorical). There is something venerable in this; however unpalatable, it is honest.

______________________________________

Little Worlds: Video Sculptures by Tony Oursler

February 21- June 23, 2013

Honolulu Museum of Art

900 South Beretania St. Honolulu, HI 96814

______________________________________

ARTiculations is a blog on culture and the arts by Carolyn Mirante for FLUX Hawaii. Carolyn is a Honolulu-based art critic and Owner/Director of the Gallery of Hawaii Artists (GoHA), an alternative exhibition space dedicated to the contemporary arts in Hawai’ i.