Text by Matthew Dekneef & Rae Sojot

Images courtesy of Hawai‘i State Archives

Breaking Kapu: When hawaiian Men and Women first Ate Together

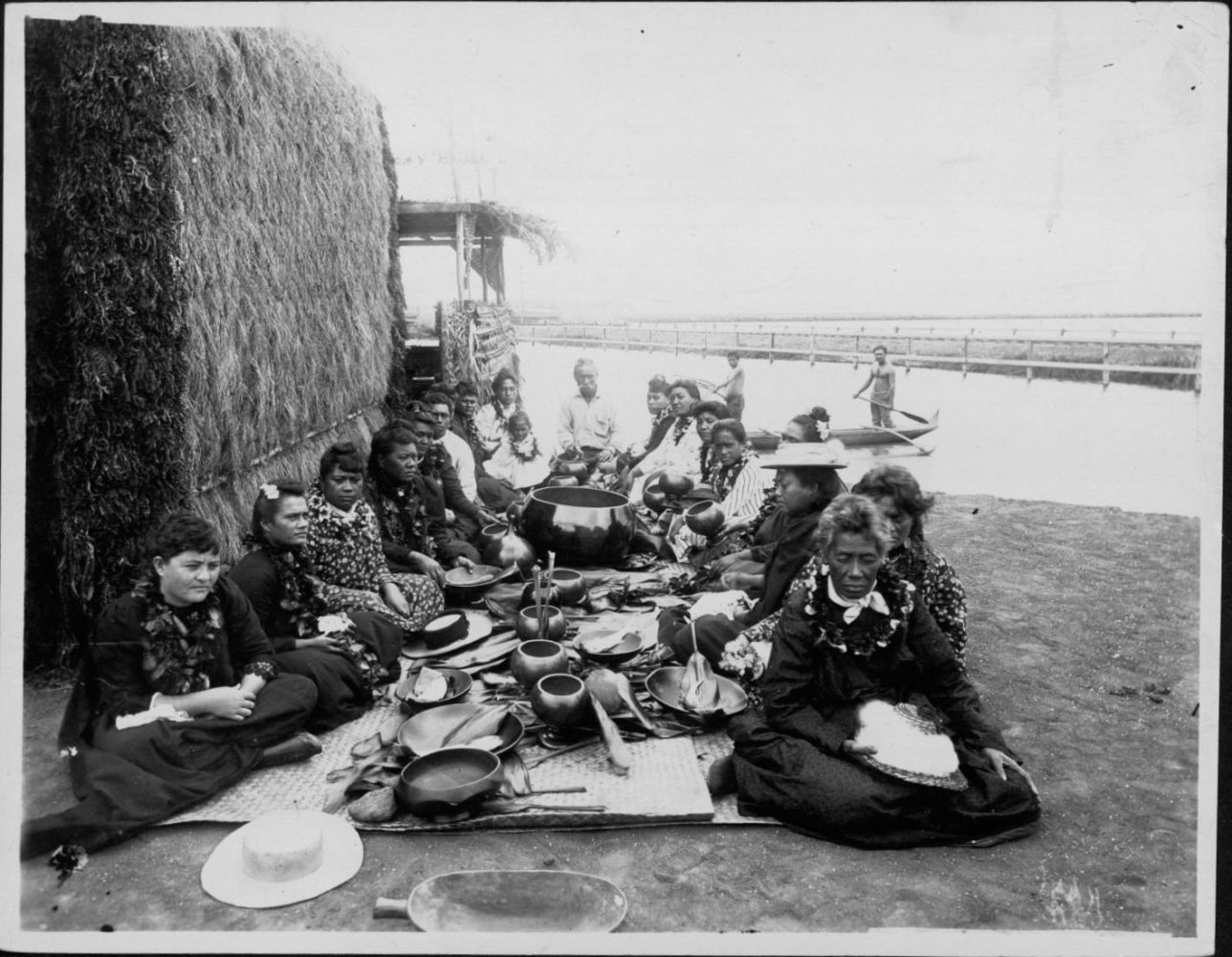

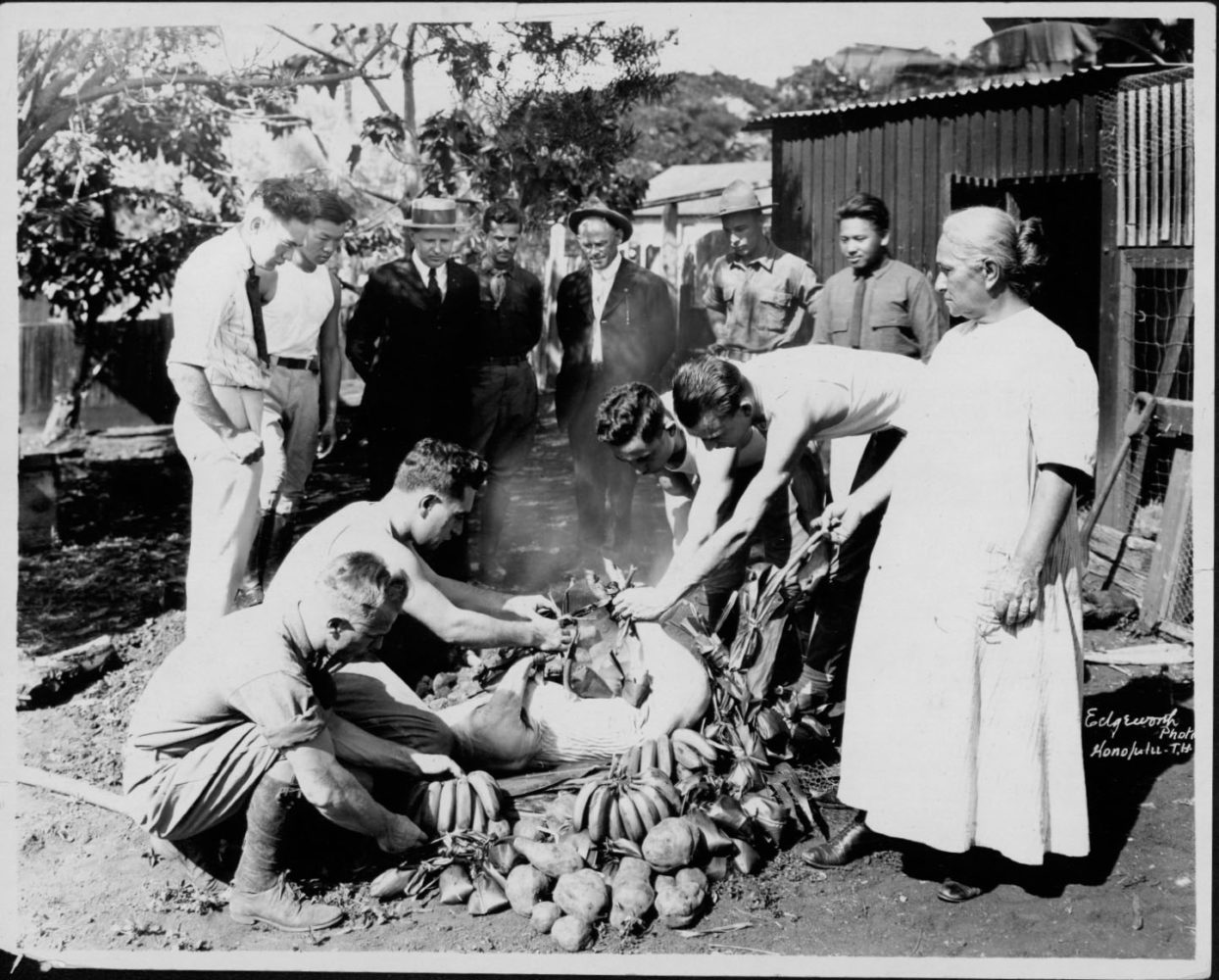

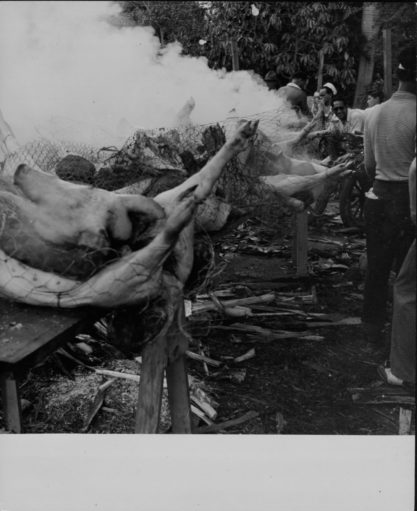

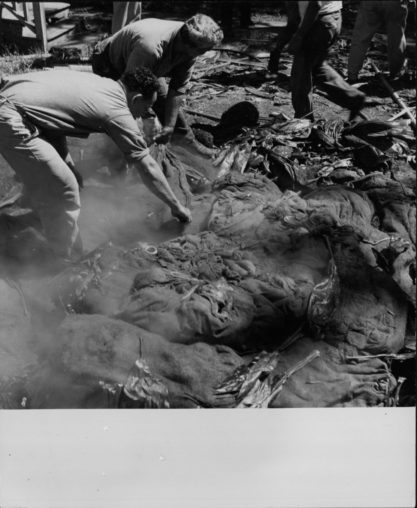

November, 1819. On the shores of Kailua, Hawaiʻi Island, the stage was unassuming, but set: two tables and woven mats—one for kāne, the other for wāhine. Seated with the women were Kaʻahumanu and Keōpūolani, two of the recently deceased King Kamehameha’s highest ranking wives, in the company of their royal female attendants. In front of them was a spread of kalo, iʻa, and limu (taro, fish, and seaweeds). Dining separately, at a generous tableau strewn with calabash bowls of puaʻa, maiʻa, kalo, ʻulu, and niu (pork, bananas, taro, breadfruit, and coconuts), the tender and savory staples of the people’s diet, were the leading chiefs of the time, sharing these foods with a handful of European male visitors. On the surface, this gendered scene was following standard protocol of the ʻai kapu, or “sacred eating” law. For centuries, this and other kapu laws, infused with political and spiritual powers, organized the daily fabric of Hawaiian society.

However, Kaʻahumanu, in alliance with Keōpūolani, was intent on ensuring that this evening’s meal would take a new course. She began by persuading Liholiho, Kamehameha’s chosen successor and Keōpūolani’s son, to call upon a dinner and surprise his brethren by explicitly breaking the ‘ai kapu by eating with the women, instead of the men. Liholiho, who was last to arrive, was visibly nervous as he entered the feast, clearly torn between upholding the framework of laws followed closely by his father or setting in motion the new progressive ideals of his mothers. He slowly circled both tables two or three times, as if considering the array of dishes being served on each.

In Hawaiʻi, food had always carried clear religious overtones. The act of eating itself was seen as communing with the multitude of godly beings Hawaiians worshipped. The women, even consorts with unquestionable political clout like Kaʻahumanu, were not considered sacred enough for such an exchange, and refrained from eating the specific foods associated with male deities, such as bananas, a land form of Kanaloa, and pork, the beastly shape of Lono. ʻAi kapu went so far as to require women to only partake in foods that had been prepared in an imu designated for their gender, so as not to defile the holy communion between a man and his pork, his bananas, his coconuts, and his gods.

Kaʻahumanu was determined to dismantle this deeply ingrained edict. Upon Kamehameha’s death six months prior, she had emerged the most powerful person in the Hawaiian kingdom, as he had decreed her the kuhina nui, the co-ruler, of his newly unified islands, alongside Liholiho. She could order that all the guns of the neighboring aliʻi be collected and taken into her possession, which she commanded following Kamehameha’s last mortal breath. On any given day, she could be wrapped in new exotic fashions gifted by European explorers, a symbol of her boundless relationship to lands and luxuries the male aliʻi didn’t possess.

Yet, she still couldn’t feast from the same bowl as any of the men. Because of this, she hungered for a change. After all, dinners, from a Western perspective, displayed the power to bring people together, not divide them, and was something Kaʻahumanu witnessed intimately during her rise to power. She indulged in ignoring the ʻai kapu often throughout her youth. In her 20s, she spent an afternoon eating in the company of a young haole lieutenant under the watchful eyes of her all-female court. She offered him fruit and sent to have coconuts, a forbidden food, gathered from a nearby tree and presented to him. While the two ate together, her attendants continued to wave Kaʻahumanu with kahili, fanning a scene they hadn’t witnessed on their ‘āina before. In her 30s, while entertaining a Russian commander, she called for a watermelon, then cut it and offered it to him with her bare hands, a sacrilegious display, since women were never allowed to touch a man’s food. In the commander’s expedition journals, he described her as one who “united a clear understanding with masculine spirit, and seems to have been born for dominion.” Most importantly, according to historians, is that Kaʻahumanu always performed these displays in the presence of other Hawaiian women. Already she was stirring an appetite for a new social dynamic among her circles.

As Liholiho orbited the segregated diners, Kaʻahumanu and Kēopūolani watched him closely. Without warning, he sat at a vacant place with the women. Beside them, he ate voraciously—a symbolic mastication of his kingdom’s concrete rules—while the astonished guests erupted in applause, crying out, “ʻAi noa! ʻAi noa!” Free eating!

The effects of this single dinner were far-reaching and immediate. With no religious mandates to follow any longer, Liholiho and Ka‘ahumanu ordered all the islands’ heiau destroyed and idols burned. Within days of the ʻai noa, their official instructions enjoining men and women to feast together of the same foods had reached Honolulu. In the diaries of a Spaniard living on Oʻahu, he noted a day in November that appeared to carry on like any other. Nothing out of the ordinary, he noted, except out along the waterfront, all the women were eating pork.

— M.D.

The Plantations: Where Local Flavors Were First Married

O‘ahu, 1918. A newly married Ayako Kikugawa proudly wrote home to her father in Japan that she had made miso soup for the first time. The 19-year-old’s burgeoning cooking skills were borne of necessity. Like many women who lived on Hawaiʻi’s plantations, Kikugawa was responsible for preparing meals for herself and her new husband. Rising before dawn each morning, she made breakfast, then packed twin bentos of rice and tsukemono, pickled vegetables, for their day’s labor in the field. When they returned home in the evening, she’d commence cooking dinner over an open fire.

From the late 19th to the early 20th centuries, Hawaiʻi’s agricultural economy boomed with the rise of pineapple and sugar empires. To satisfy these growing industries, a large immigrant workforce arrived, settled, and found a permanent home in the islands. Many of these workers were single Japanese men who desired to marry but were unable to afford passage home to seek brides. Instead, they employed the popular services of matchmakers who paired potential brides and grooms through photographs and family recommendations. Known as “picture brides,” nearly 20,000 Japanese, Okinawan, and Korean women, Kikugawa among them, left their homes and embarked on the 4,000-mile journey to Hawaiʻi, where new husbands—and new lives—awaited them.

It wasn’t easy. After an arduous 10-day voyage by sea, the picture brides disembarked and filed straight into the immigration station at Honolulu Harbor, casting curious glances toward the group of men assembled on the dock. Once paperwork was processed and a battery of physical and competency exams completed, the brides and grooms met in person for the first time, moments of anxious anticipation for both as they matched black-and-white portraits to the faces before them. A quick marriage ceremony followed on the dock, conducted en masse in groups of 20 or so couples. Any additional matrimonial fanfare was curtailed by a lack of time and finances—most newlyweds headed straight back to the camps. There, women were thrust into a new relationship with a veritable stranger and the demands of plantation living.

Life in the sugar and pineapple fields meant long days of toil under the hot sun. In addition to cooking and cleaning, women weeded the fields and stripped pineapple crowns, which left their hands raw and blistered. They dug ditches and carried heavy bundles of cut cane. When they became mothers, they brought their children along, often working with their infants strapped to their backs. But there was a silver lining: friendships, forged in the midst of hard labor.

These friendships led to shared meals, and soon, foods made on the plantation began to reflect a creative melding of the various ethnic groups that lived there. Rice, the economical and filling mainstay of the Japanese laborers, was no longer only served with miso soup and tsukemono. It found satisfying places alongside Hawaiian dried, salted akule, Filipino pork adobo, and Chinese stir fry.

As the plantation women cooked and communed together, they helped to shape local cuisine unique to Hawaiʻi. They left a lasting, tasty legacy: Their new bentos of assorted ethnic dishes served as the precursors to Hawai‘i’s beloved plate lunches.

— R.S.

The Rise of Luxury Liners: A Tourists’ First Taste of the Islands

Spring, 1953. When Los Angeles resident Rose Yampolsky boarded the S.S. Lurline bound for the Hawaiian Islands, the cruise staff provided guests with their first taste of Hawaiʻi: a celebratory “Poi Cocktail,” which blended Hawaiʻi’s beloved purple taro paste with cream and a shot of bourbon. For Yampolsky, the indulgence technically fell under doctor’s orders. Recently widowed, she had been encouraged by her psychologist “to go out, get out and do something,” grandson David Dichner recalls. So the plucky 55-year-old sought out new adventures, booking a cruise across the Pacific Ocean. “It was the glamorous thing to do back then,” Dichner says. “Hawaiʻi was exotic and faraway and that’s where everybody was going.”

It was post-World War II posterity that bolstered a surge in American travel overseas. Mesmerized by advertisements featuring swaying palms, white-sand beaches, and tropical seaside lūʻau, a robust influx of tourists arrived upon Hawaiian shores, eager to experience all things Polynesia—food included. Cruise ships served as the fulcrum of Hawaiʻi’s tourism, disembarking and boarding nearly 700 passengers via Pier 11 at Honolulu Harbor each week. The Matson Lines’ S.S. Lurline, along with her sister ships the S.S. Malolo, S.S. Mariposa, and S.S. Monterey—collectively known as the “White Ships”—glittered as the four crown jewels of its fleet of luxury ocean liners. Providing a first-class-only transit service between California and Hawaiʻi, the ships gained prestige for their glamorous accommodations and amenities. By capitalizing on the allure of paradise, these cruises proved instrumental in establishing Hawaiʻi as a world-class destination. In 1955, tourist arrivals numbered 109,798. Within two decades, the arrival numbers had swelled well into the millions.

The S.S. Lurline’s luxuriousness was legendary in attracting hoi polloi and celebrities alike. John Wayne and Clark Gable were special guests, as were Shirley Temple and Elvis Presley. The weeklong crossing allowed for shuffleboard and movie screenings, trap shooting and tennis. When not reclining in their air-conditioned three-room “lanai suites,” guests could swim in a seawater pool or indulge in champagne parties and midnight buffets. Dining was an extravagant affair, offering a preliminary if not downright regal taste of the islands: opakapaka meunière with buttered cucumbers, clear turtle soup with Amontillado sherry, fresh frosted pineapple au crème de menthe. Even the menus that announced such dishes were posh, graced with vivid murals by artists like Eugene Savage that captured the gaiety of tropical island culture, as commissioned by Matson Lines.

These meals were merely appetizers before the overall travel experience. Upon arrival in Honolulu, guests received a jovial welcome. Outrigger canoes sidled up to the ship, shouting warm greetings. Thousands of fragrant lei were bestowed upon the debarking travelers. Along the crowded dock, women danced hula and musical groups sang “hapa haole” music to the tune of ʻukulele and steel guitar. For guests of the S.S. Lurline, their Hawai‘i adventures were about to begin.

— R.S.