In art, as in life, men are constrained by old notions of masculinity. How do we break the mold?

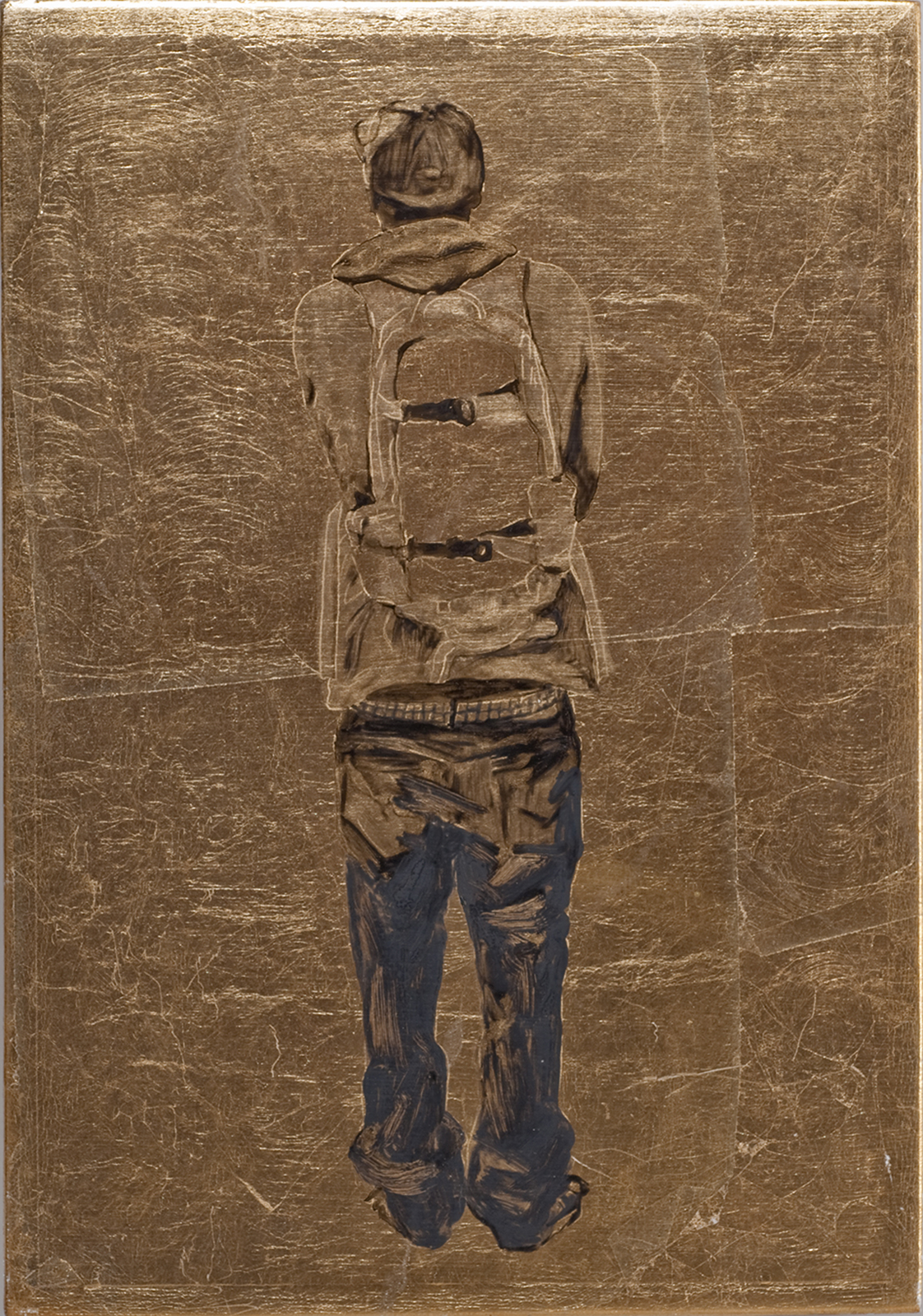

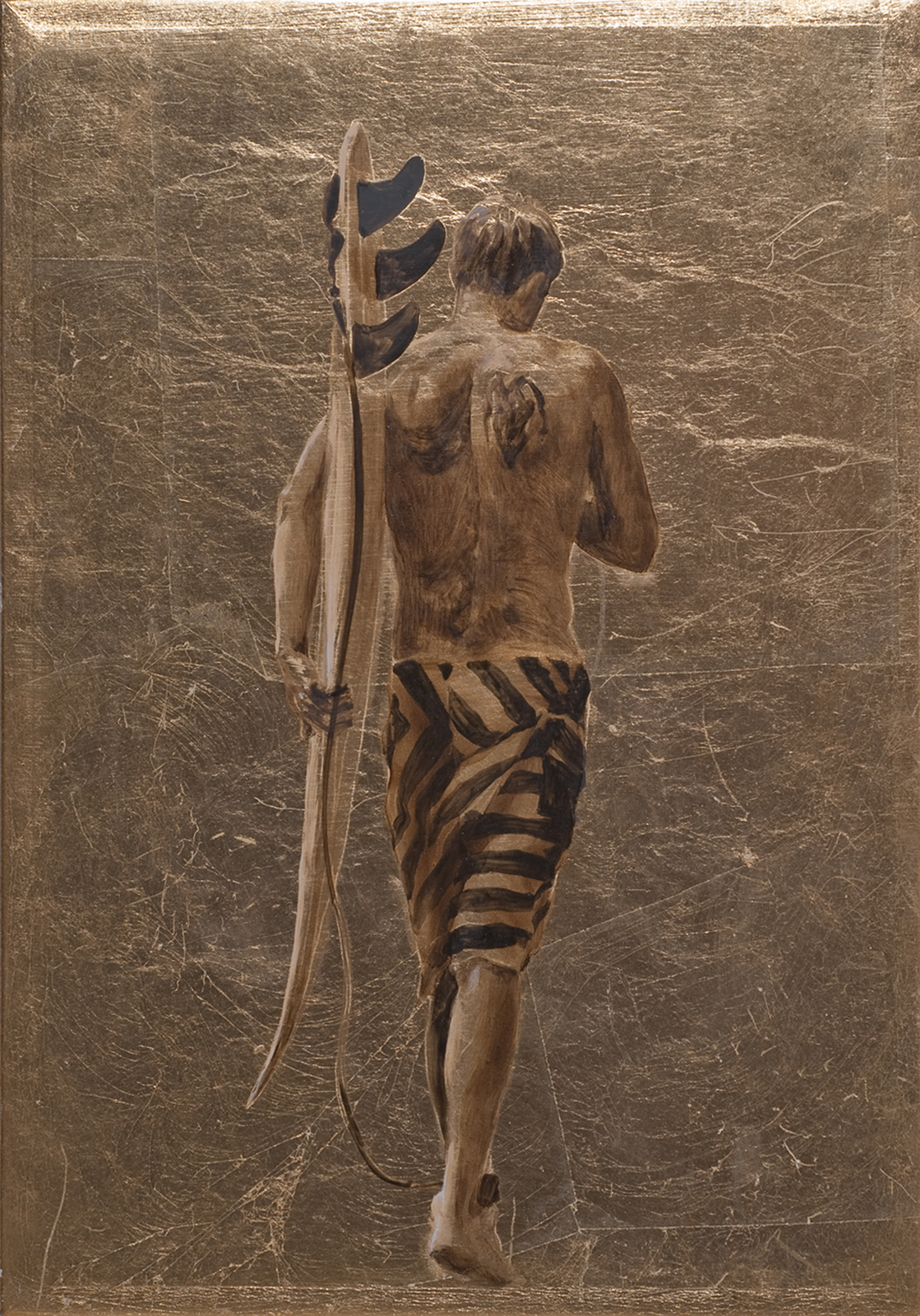

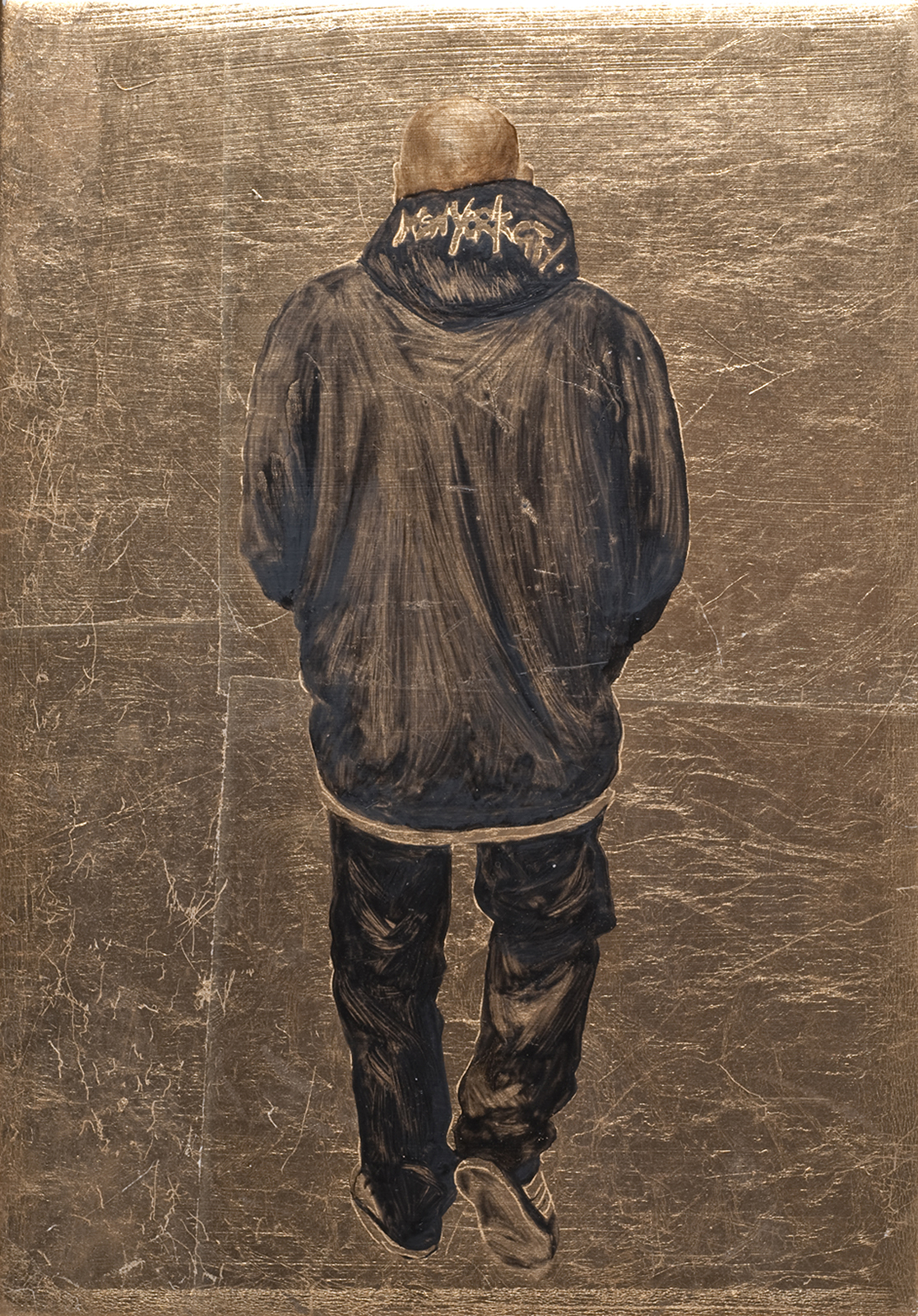

The men are alone. That’s the first thing I notice. Despite their differences—for they are old, young, black, brown, Czech, Hawaiian, heavy, slender, muscular, soft, real, symbolic, and fictional—almost all of the figures in MEN, an exhibition that debuted in September 2018 at the Hawai‘i State Art Museum, are depicted solo.

This isn’t so unusual. A portrait is, almost always, the study of an individual. Many artists begin by drawing the human body, and that body, too, is often a lone figure in a room. And yet there is something profound in the bodies of the men here, not least because, besides being alone, many of their faces are obscured. They show us their backs.

Too many boys are trapped in the same suffocating, outdated model of masculinity, where manhood is measured in strength, where there is no way to be vulnerable without being emasculated, where manliness is about having power over others.

The second thing I notice is that, again with exceptions, the men are all doing something. They dive beneath the waves or bend over fishing nets. They hunt or surf or plant rice in dark paddies. Elizabeth Baxter, the show’s curator, said she didn’t select such images intentionally, but that’s the beauty of art: Even in a collection as small as the museum’s Art in Public Places collection, from which the exhibit was assembled, one can start to see patterns. That so many of the men in MEN are frozen in action says something about us.

The question is: What? What does it say that when we look at men, we largely see them as archetypes concerned with age-old tasks of hunting and gathering?

The exhibit, which spans the century between 1910 and 2010 and features work by Francis Haar, Carol Bennett, James Surls, and Jean Charlot, among others, leaves the question largely unanswered.

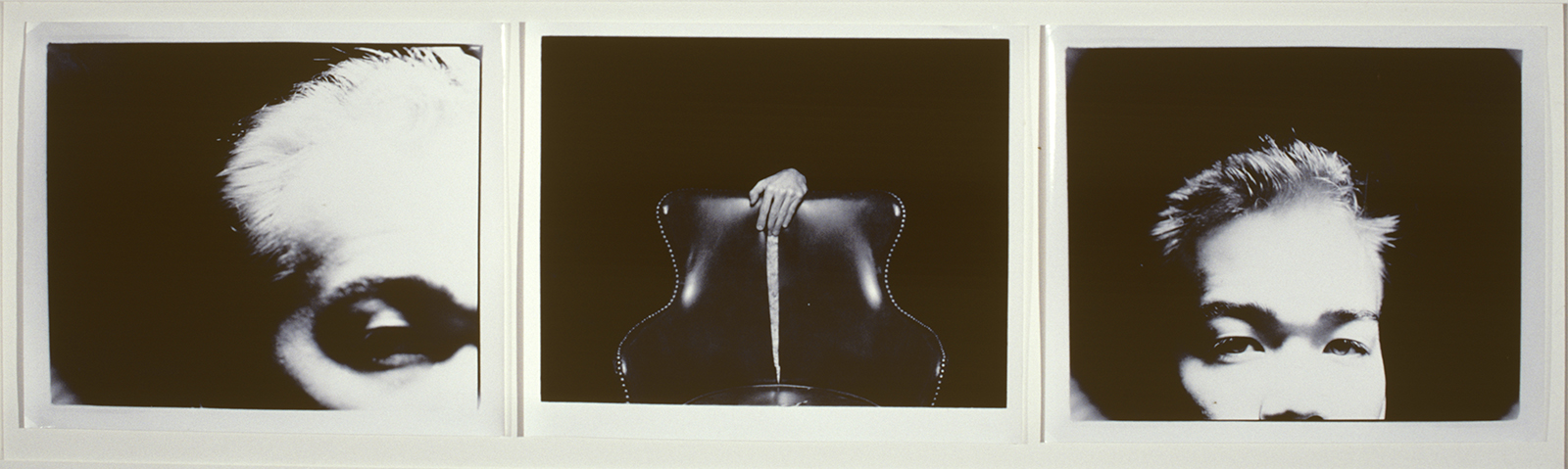

Only a few pieces, such as Melinda Morey’s series on young men’s public posturing or Rick Allred’s La Bouche, address the topic of masculinity directly. And yet somewhat inadvertently, the show joins a much larger conversation. In the past few years in the United States, there has been an explosion in the number of people trying to answer a very basic yet very complicated question: What does it mean to be a man?

New York Magazine devoted an entire recent issue to the topic, as did the podcast Death, Sex, and Money, while Devin Friedman published a meditation—in GQ of all places—on the sad lack of intimacy in male friendships. In the wake of #MeToo, discussions of toxic masculinity now can be found in the unlikeliest of places, such as Playboy, which published an exploration of the science of extremism featuring the work of Michael Kimmel, the executive director of Stony Brook University’s Center for the Study of Men and Masculinities.

It can also be found in think pieces about the Harry Potter spin-off Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them, whose highly sensitive, deeply human protagonist, Newt Scamander, has been praised for existing outside the macho mold of the typical Hollywood hero.

Or in the national conversation surrounding the death of Anthony Bourdain, who publicly called out chefs who harassed women but also examined his own role in perpetuating the restaurant industry’s toxic culture. “Bourdain’s death is the loss of an ally,” penned one female writer.

Understanding what men are being taught has become an urgent task, and not just because every day seems to bring new sexual assault allegations. There is also a growing awareness that we are poisoning ourselves. According to a 2018 poll of 1,000 kids aged 10 to 19 in the United States by PerryUndem for PLAN International USA, while the definition of what it means to be a girl has gradually expanded—the result of decades of hard work by women—boys continue to be taught that the number one thing a man should be is “tough.”

“Too many boys are trapped in the same suffocating, outdated model of masculinity, where manhood is measured in strength, where there is no way to be vulnerable without being emasculated, where manliness is about having power over others,” Michael Ian Black wrote in a New York Times op-ed in early 2018. “They are trapped, and they don’t even have the language to talk about how they feel about being trapped, because the language that exists to discuss the full range of human emotion is still viewed as sensitive and feminine.”

Black was responding to the mass shooting in Parkland, Florida. As of September 2018, there had been 104 mass shootings in the United States since 1982, and all but three of them were committed by men. Men are also responsible for the vast majority of rapes, sexual assaults, and instances of domestic violence in this country. Our violent rage is also aimed inward. Men commit suicide at more than triple the rate of women; in the United States, roughly 80 men kill themselves every day.

At least part of why men are prone to violence is because we are taught that vulnerability is a sign of weakness. As a result, as men get older, our relationships, especially with other men, tend to fade. Our social circles become smaller and smaller until we find ourselves more or less alone. This sort of social isolation, we’re learning, can be just as deadly as physical violence. Researchers now believe that loneliness is a much greater public health epidemic than obesity, able to increase mortality risk by as much as 50 percent.

If men are struggling, we have only ourselves to blame. We mistook our power for strength. We believed our own hype. We couldn’t see the warning signs, or if we did, we largely ignored them. In our silence, we forced women to do our emotional thinking for us. We outsourced to women any question about how we ought to behave in the world. We rely on women to tell us, “This is OK. That is not.” We ask women not only to suffer our boorishness but to fix it too.

Art and film have romanticized the image of the lone male hero, but rugged individualism is less rosy in real life. It comes at a price. While men retain the power in a patriarchy, we are also imprisoned by it, taught to assert ourselves but only in ways that do not threaten the system. Like war, patriarchy maims even the victors.

Standing in the gallery at the Hawai‘i State Art Museum, I think about the ways that I’ve internalized messages about shame, weakness, vulnerability. I never bought into the idea of machismo; I’ve been the shy, sensitive guy for as long as I can remember. Still, it seeps in. Like a muscle, our ability to be emotionally honest can atrophy. It’s taken three years of therapy to decode the breadth of my own feelings and learn how to access them in real time. And I still have a long way to go.

Clearly, more than ever, there is a need for men to listen to the women in their lives—at home, at work, in school, on the field. But men also need to seek out one another, not for empowerment, but for help. We have to unlearn what we were taught as boys and instead remind each other that it’s OK to be vulnerable, to look “weak.” Looking weak takes tremendous courage.

After I leave the exhibit, I find myself meditating on one image in particular, a black and white photograph by Robin Kaye, who documented Lāna‘i throughout the 1970s. The work is named for its subject, Jonathan Mano, who in the photograph wears a loose-fitting T-shirt and smiles proudly as he leans on the carcass of a huge pig, which is stretched out on a table, its skin sagging in huge, long folds.

At first glance, the image is full of all the old symbols: physical strength, violence, death. But then we read that the pig was not wild. Mano raised it for the occasion, a lū‘au that was about to take place. The circumstances of the animal’s death are a clue to something else as well: Mano is part of a community. A lū‘au is not a solo event but a raucous, often celebratory feast, full of uncles, aunties, cousins, friends. In his book, Lāna‘i Folks, Kaye wrote that the preparations for one lū‘au took months and, during those days beforehand, “It was as if the party had already begun.”

We know very little about Jonathan Mano and nothing of his wellbeing in the moment that Kaye made his picture. But his is one of the only smiles in the exhibit. And at least a portion of his happiness seems to come from his participation in this communal ritual. I wonder: How can men recover this kind of community? To start, we’ll have to admit that community requires human connection and human connection requires vulnerability. A lot of men are learning this. I’m learning it. As I do, life gets a little bit easier, for me and for those around me.

Shortly after Mano posed with his pig, the animal would have been hauled to the imu. It would have been set on a bed of kiawe wood and red-hot stones, itself the result of much hard work performed by dozens of hands. What we see in the photo is a solitary man, but Mano is not alone. A party is about to begin. The feast is imminent.