An omnipresent artifact of midcentury modernism, the humble breezeblock is an undeniable yet overlooked aspect of Honolulu’s urban fabric. Is it poised for a comeback?

Images by John Hook

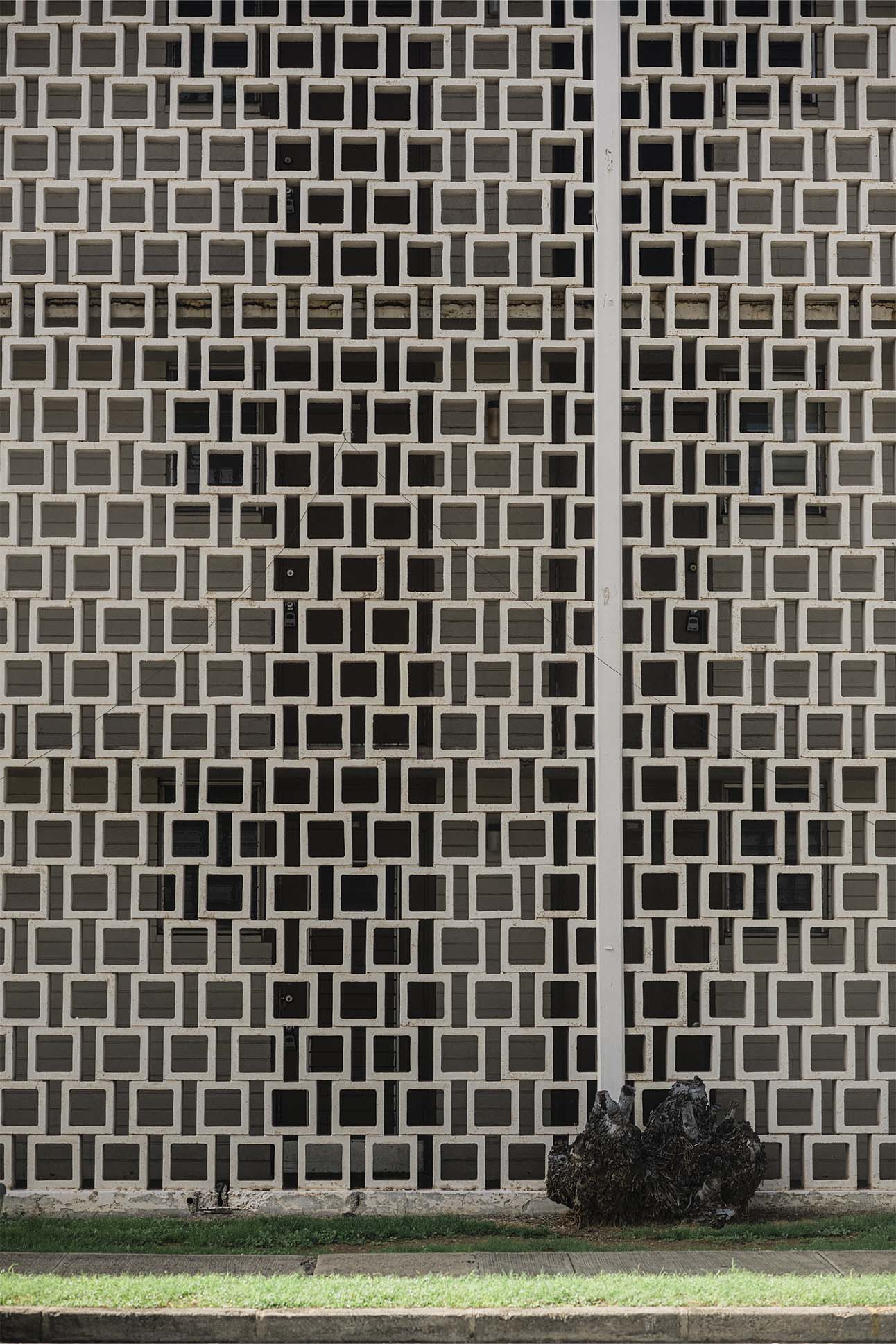

One of my more embarrassing moments as a design writer took place on Instagram in 2015. My wife and I had just moved to Honolulu from Chicago to be closer to her parents, renting a studio apartment off of the Ala Wai Canal. As I explored the neighborhoods within walking distance of our building — Mōʻiliʻili, Diamond Head, Waikīkī — I noticed the same architectural detail over and over: small, hollow concrete blocks, typically with some sort of shape or pattern in the middle, like those snowflakes children cut out of paper. Entire walls were made out of them, the repetition of dozens, even hundreds of blocks stacked on top of one another creating an even larger, more intricate pattern. The effect was an architecture that felt both solid and porous, sturdy and fragile. I was mesmerized.

I didn’t know what these blocks were called, or if they had a name at all, so I snapped a photo and posted it to my Instagram account. “I’ve been wondering for months if there’s a technical term for the concrete facade detailing that’s on everything here. Anyone know?” My friend and fellow writer Lindsey wondered whether they might be a modern type of mashrabiya, the ornate, wooden window screens common in Islamic architecture. A few others hazarded guesses as well. It was local curator and community developer Wei Fang — then of Interisland Terminal, now of Arts and Letters Nuʻuanu — who eventually supplied the answer. She wrote one word: #breezeblocks.

I learned soon after that practically everyone in Hawaiʻi knows what breezeblocks are and was retroactively mortified to have outed myself as yet another clueless mainlander. I shrunk at the imagined jeers. An architecture critic who doesn’t know what breezeblocks are? Sheesh.

In retrospect, I needn’t have felt so embarrassed. My experience is a common one for people who grow up in the chillier or more rural parts of North America. Jason Selley and Lance Walters, who now run the Instagram account @breezeblockboutique, both discovered breezeblocks only after moving to Honolulu. “Hawaiʻi definitely was the first time I tuned into breezeblock,” said Selley, who grew up in Nebraska. (A quick note: Architects tend to refer to breezeblock, singular, as in “Breezeblock came into fashion in the 1950s and ’60s.” It’s sort of like brick. A wall is made out of multiple bricks, but you say it’s made out of brick. Breezeblock is also sometimes referred to as screen block or textile block.)

Although breezeblock has recently been nudged back into popularity thanks to a broader appreciation for midcentury modernism, it still doesn’t get the love it deserves, Walters said. “Even though it is having a moment, I think it’s still kind of under-appreciated,” he said.

This under-appreciation is partly why, for the past decade, Walters has used breezeblock as a core part of his Architecture 102 class at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa. It’s the perfect introduction to Hawaiʻi’s built environment, he explained. “It’s easy for the students to draw, and it’s something that they’ve all been around but not paid attention to. It draws their eye to a new aspect of architecture that’s just lurking in their backyard.”

Students in Walters’ class document examples of breezeblock in their neighborhoods, adding them to an online database that Walters has maintained since at least 2017. It currently has nearly 2,000 entries. Students then design their own block pattern, 3D-printing miniature models before casting a full-size block out of concrete using a wooden mold. Walters keeps an assortment of the 3D prints in his university office. “I probably have 10,000 of these little Lego-size blocks,” he told me.

If breezeblock is experiencing a kind of low-level renaissance in Hawaiʻi, a big part of why is that it is democratic, unfussy.

Unlike some building technologies, breezeblock doesn’t have one single “inventor.” Rather, the idea of decorative concrete blocks seems to have emerged in multiple corners of the world in the late 1910s and early 1920s, simultaneously appearing in buildings in Brazil, France, and California. As the architectural historian Don Hibbard writes in his forthcoming booklet on breezeblock, published by Docomomo Hawaii, “As early as 1917, [Frank Lloyd] Wright had begun to experiment with what he called ‘textile blocks,’ concrete blocks impressed with geometric or floral patterns to form decoratively patterned walls.” Wright reportedly hated concrete block and so set himself the challenge of finding ways to beautify what he called the “gutter rat” of architectural assemblies. He eventually used his proto-breezeblock to great effect in the richly textured, Art Deco-inspired Millard House in Pasadena, California, built in 1923 — the same year French architect Auguste Perret completed Notre-Dame du Raincy outside Paris, a modern take on the gothic cathedral that is wrapped in a patterned concrete screen.

Breezeblock hit the mainstream in the late 1950s, following the opening of the U.S. Embassy in New Delhi, India, designed by New York architect Edward Durell Stone, the person arguably most associated with breezeblock façades. (Stone eventually patented one of his screen block patterns.) Stone’s use of breezeblock has been described as an architectural analog to pop art, though unlike Yayoi Kusama or Andy Warhol, whose art was a commentary on consumerism and mass production, Stone and his contemporaries seemed to deploy breezeblock uncritically, exploiting its means of production without comment. In a way, it was the epitome of modernists’ belief in the beauty of functionality. Breezeblock was ornamental, yes, but it wasn’t ornamental for ornament’s sake. (Still, some found it overly romantic.)

The 1960s and ’70s saw a proliferation of decorative breezeblock screens, perhaps nowhere as noticeably as Honolulu, then in the middle of its post-Statehood building boom.

Why breezeblock became ubiquitous in Hawaiʻi comes back — like a lot of its architecture — to the islands’ climate. Enabled by advancements in concrete fabrication and rises in the costs of labor and traditional building materials like stone, breezeblock became a cost-effective way to screen buildings from excessive sun while also allowing for natural ventilation, making it particularly popular in hot and humid climates, like those of Hong Kong, Miami, and Honolulu. A concrete breezeblock wall had the added advantage of high thermal mass, meaning it absorbed the sun’s heat during the day and released it at night, making it well-suited to desert locales like Palm Springs. In this way, my friend Lindsey wasn’t far off. Like Islamic mashrabiya, breezeblock is an example of geographically influenced, climate-responsive architecture, used to create what might be seen as chunkier, more modern versions of European brise-soleil or Indian jali.

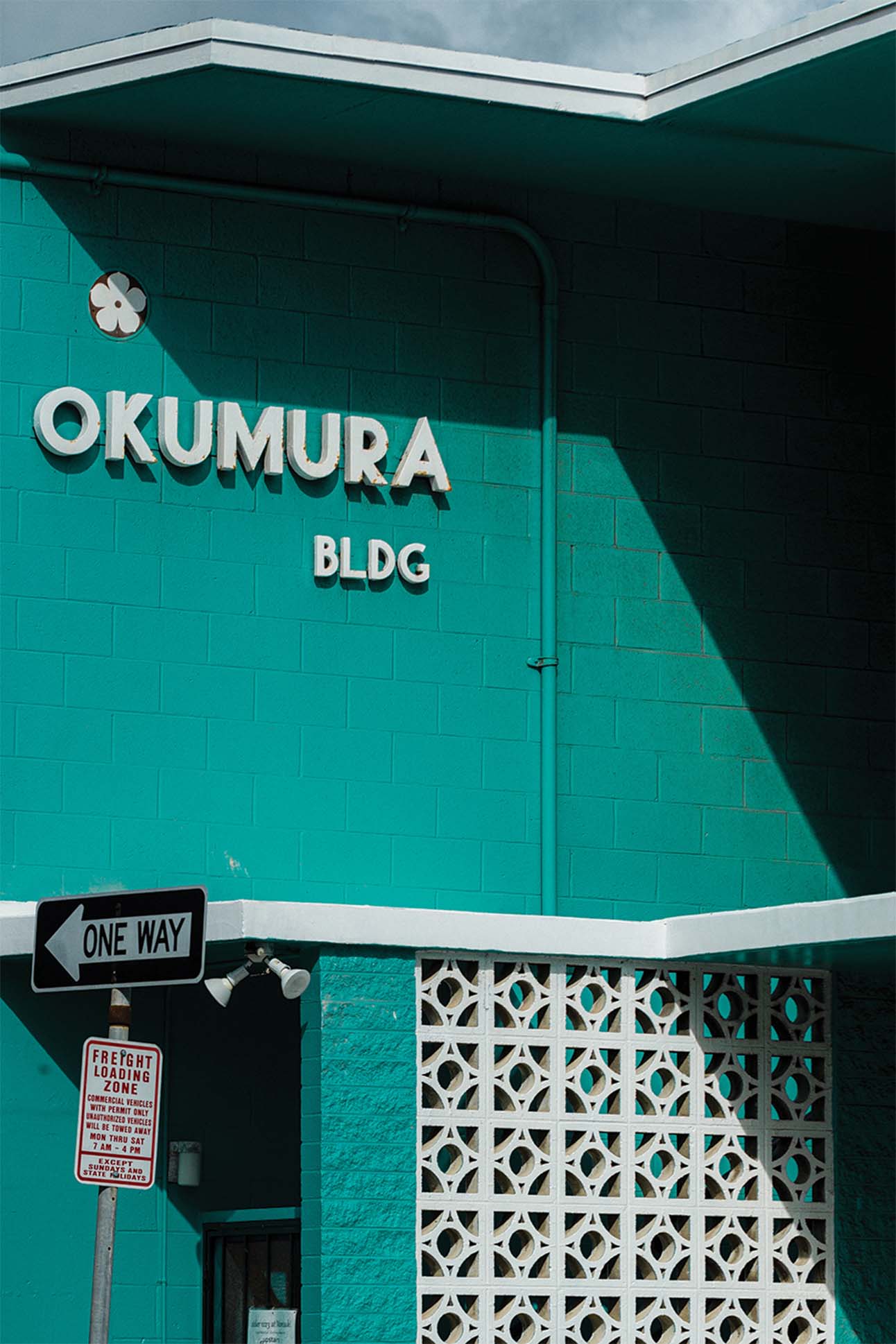

Breezeblock was also cheap to produce. Thousands of blocks could be made with a single mold — “Play-Doh Fun Factory-style,” Selley said. Concrete masonry companies began offering standard shapes and patterns, which architects could select from their catalogs. Even today, local companies like Tile Co. in Kapolei offer a selection of screen block options. #399, for example, is a square block with what looks like an elongated, four-petaled plumeria flower in the center. For architects working in Hawaiʻi, breezeblock had (and still has) the double advantage of being produced locally, eliminating exorbitant shipping costs. Breezeblock was smack dab in the center of a collision of history, economics, technology, and style.

The 1960s and ’70s saw a proliferation of decorative breezeblock screens, perhaps nowhere as noticeably as Honolulu, then in the middle of its post-Statehood building boom. Today, the artifacts of that period are omnipresent. Breezeblock can be found in houses, hotels, banks, bowling alleys, university buildings, and Board of Water Supply pump stations. Among a subset of local architects, including Selley and Walters, this ubiquity makes breezeblock one of the more recognizable, and therefore more approachable, threads in Hawaiʻi’s urban fabric, made all the more significant by its transcendence of class boundaries.

Today, you’re as likely to find breezeblock on the sun-baked streets of Pālolo as you are on the shady sidewalks of Waikīkī’s Gold Coast. That’s because breezeblock offered architects near-infinite customizability at almost no extra cost, making it particularly appealing on projects with modest budgets. In Honolulu, “there’s a lot of cookie cutter, plantation-type homes,” Selley said. A home’s breezeblock pattern was the “one area where architects could flex some creativity within a standard module.”

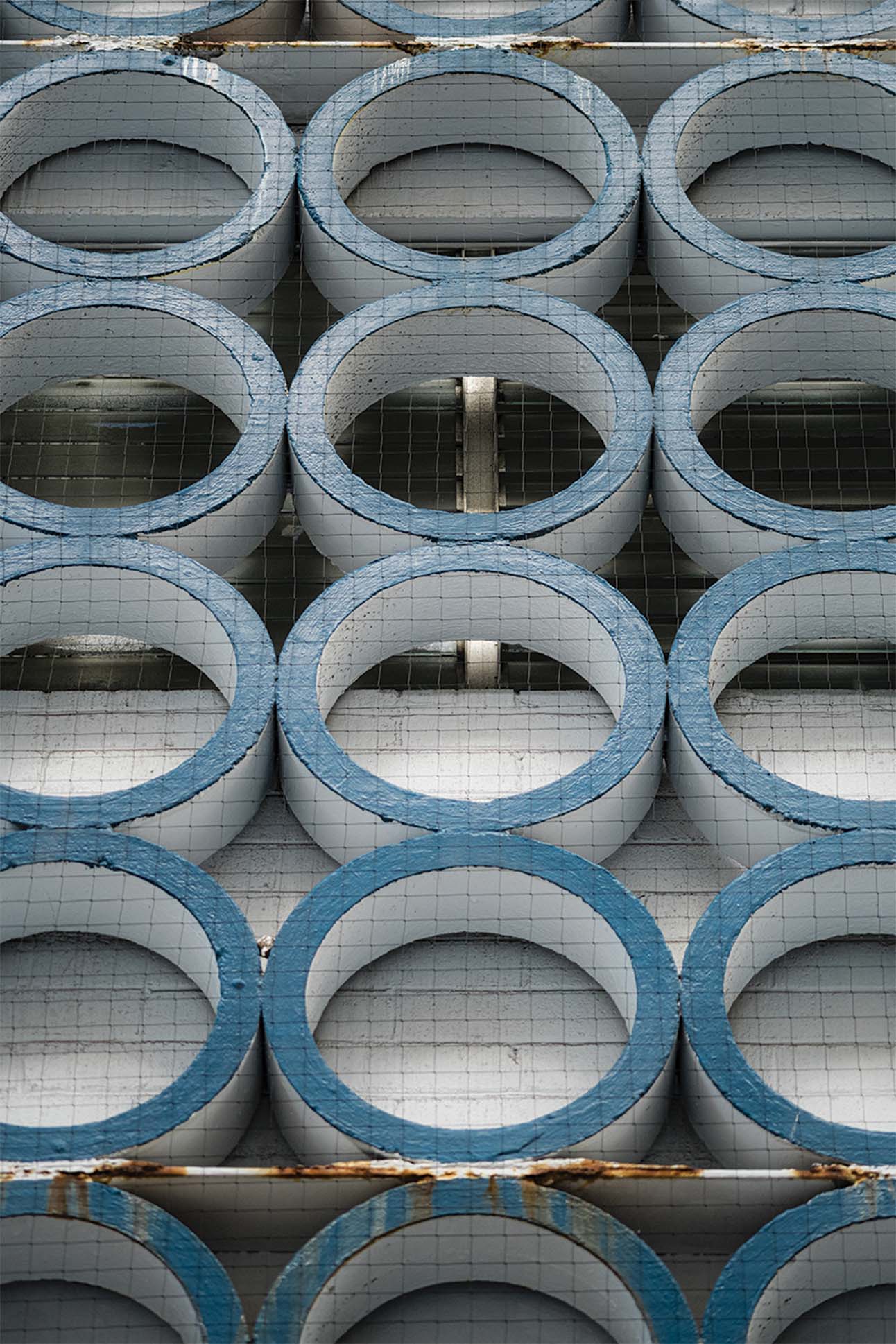

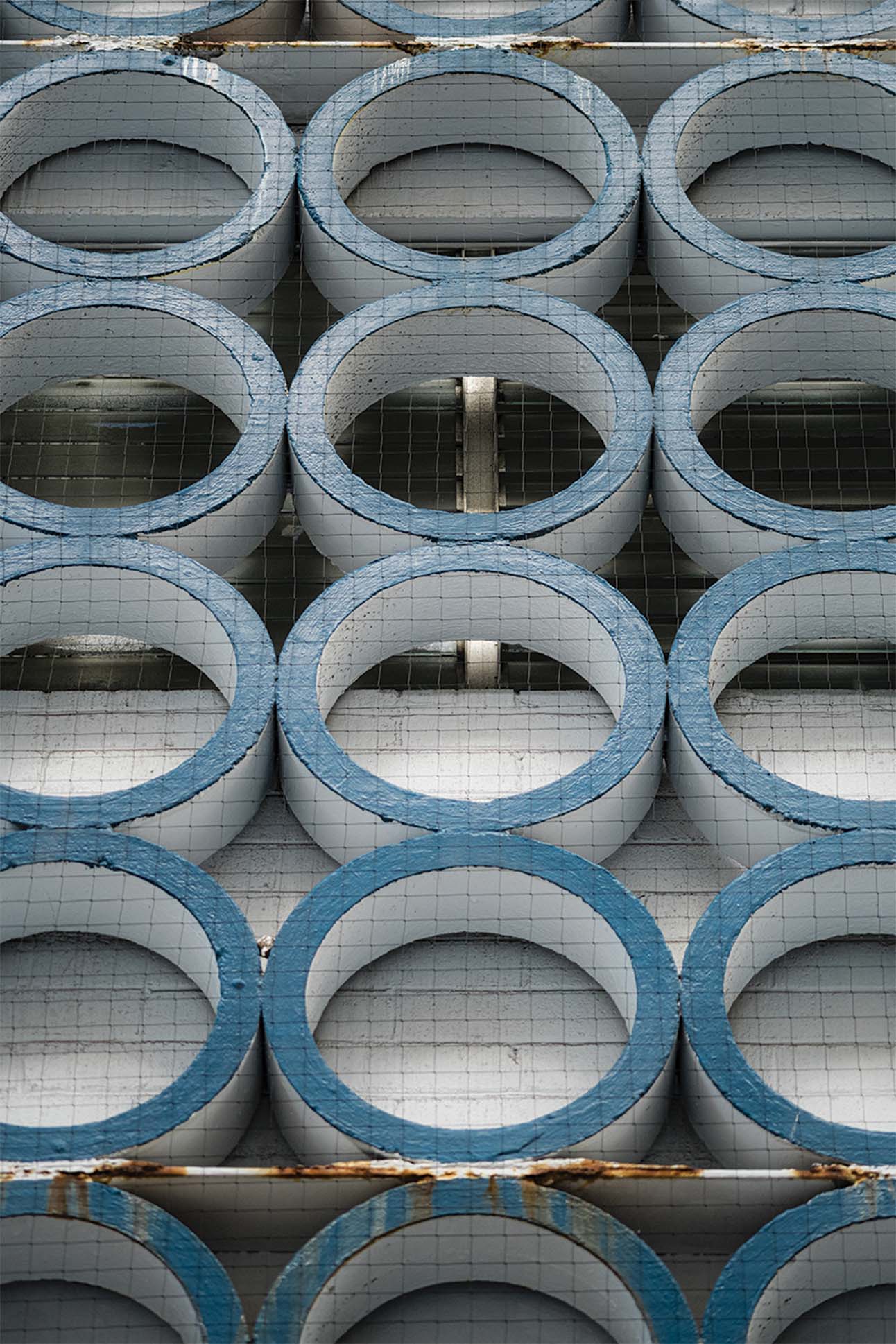

Walters and Selley have become some of breezeblock’s biggest boosters in Hawaiʻi. Under the banner of @breezeblockboutique, they’ve fabricated breezeblock-inspired coasters, ice cube trays, and most recently, with the apparel designer Roberta Oaks, a line of aloha shirts featuring the block pattern of the Pali Lanes bowling alley in Kailua, as well as other prominent styles. For Mud Hen Water, the now-beloved Ed Kenney outpost, Selley’s firm, Workshop-HI, repurposed standard, workaday breezeblock as an elegant interior element, cladding the base of the bar and window around the kitchen with Tile Co.’s #414, a rectangular block that when counterpoised forms an abstract pattern of circles and intersecting lines. “We thought it’d be a fun juxtaposition, having the old school breezeblock with a really beautiful, white marble top on it,” Selley said.

Selley and Walters are also working to design their own contemporary breezeblock, inspired by traditional Hawaiian kapa patterns, for an apartment project in Waikīkī. It would be a first-of-its-kind, not only architecturally but in terms of the block’s carbon footprint. Right now, concrete accounts for a huge percentage of global carbon emissions, largely due to the coal that’s burned to produce ash, a key ingredient in cement. This massive environmental cost is actually right there in the name breezeblock, Walters explained. Just as the “brut” in Brutalism comes not from the English word “brutal” but from the French phrase “béton brut,” meaning raw concrete, the “breeze” in breezeblock does not, as I had assumed, refer to its passive ventilation properties, or even to its architectural ancestor, the brise-soleil. Rather it refers to coal ash, technically known as coke breeze, which is added to most concrete mixes.

To reduce the carbon footprint of their breezeblock, Selley and Walters envision using CarbonCure technology, a method of capturing waste carbon dioxide from natural gas plants and injecting it into concrete, where it mineralizes into carbon carbonate. This prevents the carbon dioxide from ever entering the atmosphere, even if the concrete structure is demolished. The ultimate goal, Selley told me, is a carbon-sequestering breezeblock, which would store more carbon than is produced by making it.

If breezeblock is experiencing a kind of low-level renaissance in Hawaiʻi, a big part of why is that it is humble, democratic, unfussy. An echo of the past, it speaks to our desire for continuity in the midst of change, for signs and symbols that say to us, You belong here. Amid ever-more-inaccessible, all-glass towers and an increasingly virtual world, concrete blocks are tactile and refreshingly solid. At the same time, any newfound popularity may owe something to that virtual world, specifically to social media platforms like Instagram. In a 2014 essay on architecture and virality, Alexandra Lange wrote that the life-inside-a-thumbnail experience of Instagram rewards particular modes of presenting architecture: “Grids, shadows against a wall, baby Thomas Gurskys of the repetitive commercial landscape.” What architectural element is more perfectly suited to that format than breezeblock? Beautiful grids inside of beautiful grids, each neatly obscuring what’s behind them.”

I’ve also begun to wonder if architects’ embrace of this way of decorating buildings, and the public’s appreciation for it, may stem from the simple fact that it’s fun. Breezeblock invited modern architects to play. A single block could be flipped around or turned upside down to create new patterns. It was a totally new way to decorate façades, and yet there was something old-fashioned about it, almost reminiscent of those early childhood rites of passage of making shapes and stacking blocks.

I’ve been playing with blocks a lot lately. Our son turned one in December, and his room is slowly becoming filled with blocks. Small, worn, wooden ones and big, multicolored ones, each side stamped to look like bricks. I watch him put the smaller ones in the back of a little wood truck, his spatial comprehension and dexterity seeming to evolve in real time. Admittedly, he’s still mostly in the demolition phase, but soon, I know, he’ll be building towers or entire miniature cities, assembling blocks in intricate and surprising ways. Sitting next to him, I sometimes build my own funky structures. I find immense pleasure in doing so. The tactility of the material feels almost sensuous after hours of typing on plastic keys or cradling my sleek, vapid phone. And the process of arranging the blocks is both stimulating and meditative, my hands working almost of their own volition, the possibilities contained within a floor-full of red, yellow, and blue rectangles meaning that I’ll never exhaust the blocks’ potential.

I detect an only slightly more sophisticated appreciation in Selley’s voice when he tells me about another new breezeblock pattern, this one designed by an artist in Australia, that he’s using for a project in ‘Āina Haina. “It’s fairly simple,” he told me. “It’s just a triangle that you can flip to get different shadow lines, which is really the fun thing that adds more variety to the block, playing with the positive and negative, what you’re getting with shadows and light coming through.”

Breezeblock may be past its heyday, but hidden in its many forms is a recognition that the world is a vast and varied place, and that how we build can — and should — acknowledge that. At its best, architecture tells us where we are. It’s a record of how previous generations lived, what they valued, and why. For many of us, Honolulu’s breezeblocks are simply a backdrop, invisible in their omnipresence. But this humble detail encapsulates much more than crushed stone and coal breeze. It holds the stories and histories, preoccupations and aspirations, of those who came before us.