A reflection on the influence of one of Hawai‘i’s most inexhaustible creative forces

“There’s a number 10 thread that goes through art history, a thin line that goes from one generation to the other—like Rembrandt, Picasso, all different works of art. I always wanted to be part of that and strive for it. Does the world put Satoru into that? We don’t know yet, because time is the judge.”—Harry Tsuchidana

On a warm Saturday morning, a steady stream of people trickles in and out of Satoru’s Art Gallery, a plain two-story walk-up behind Old Stadium Park in Mo‘ili‘ili. News of the gallery’s imminent closure after nearly a decade has gotten around, and patrons, friends, and family have come to pay their respects to the beloved artist, browse the immense collection of his sculptures and paintings, and of course, purchase.

The gallery’s namesake, Satoru Abe, pauses to take a picture with a woman. In front of them stands a wooden sculpture about two feet high with bronze petals flowering from the top; beneath it, the $20,000 price tag has been covered with a red dot. After a cursory glance around the gallery, I count five more red dots below similar pieces less than an hour into the opening. “Who do I make the check out to?” asks a man dressed in slippers and shorts.

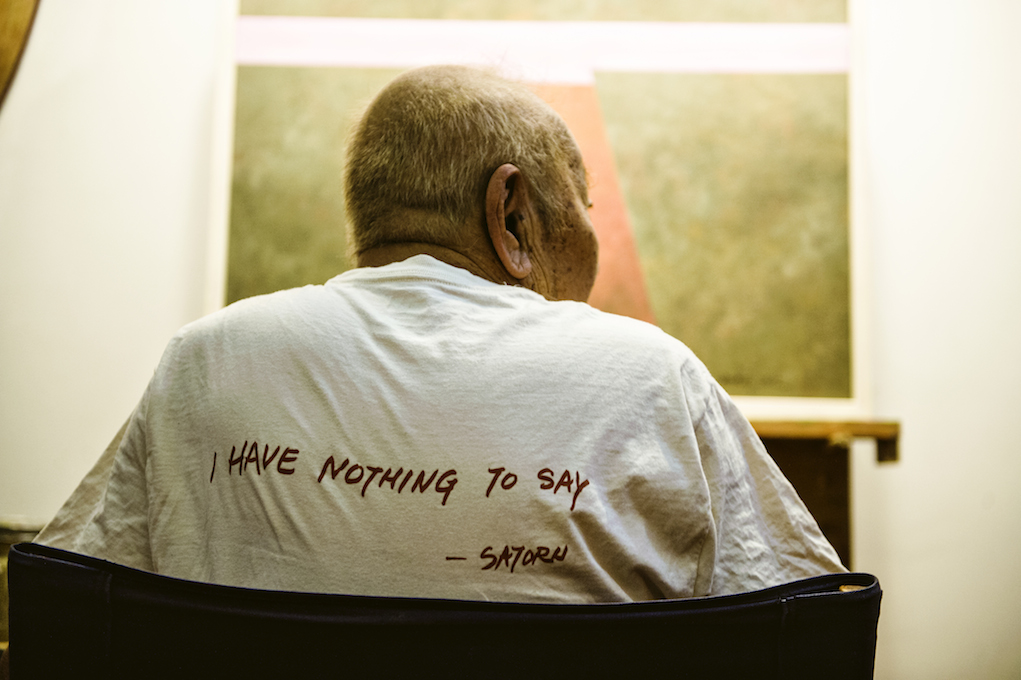

When I first asked Satoru for an interview on his influence as one of Hawai‘i’s most prolific artists, he humbly declined. “No, no, I talked too much already,” he says. And he has talked plenty. Google “Satoru Abe” and his life is in plain view: how he grew up in Honolulu as a Japanese American; how he, at the age of 22, “saw the light” while working as an assistant pasteurizer at Dairyman’s (now Meadow Gold); how he struggled as an artist to make ends meet in New York and met the love of his life Ruth, while they attended Arts Students League; how he, upon his move back to Hawai‘i in 1950, rose to acclaim with the Metcalf Chateau, his gang of local boys that included Tadashi Sato, Bumpei Akaji, Bob Ochikubo, Jerry Okimoto, Edmund Chung, and James Park, all of whom have since passed but were pivotal in introducing abstract expressionism (the playfully rebellious form that arose in New York City after WWII) to Hawai‘i; how he honed his artistic ability at New York’s Sculpture Center and returned to Hawai‘i in the ’70s; and how he, over the next four decades, would become one of Hawai‘i’s most beloved—and most commissioned—artists of all time, passionately devoted to his work and to the work of others.

And since a man cannot be all things to all people, I talked to four of those who know Satoru best about the influence of Hawai‘i’s most renowned of artists. Slowly, an impression began to emerge.

Satoru: The Friend

“His work, it’s like a multiple orgasm,” 82-year-old painter Harry Tsuchidana tells me. “Because he get lot of things going on in it. Mine, I have one orgasm; after that you smoke.”

For those who know Tsuchidana, conversations like this are typical. In the 180 minutes I spend at his home studio in Salt Lake, our talk runs the gamut of hysterical to obscene. We talk about astrological signs and how they’re excellent conversation starters; how he learned to draw by tracing comic books and that he’s older than Batman by seven years but younger than Superman by ten; and how the work that will stand out most after Satoru has passed will be cock. “Chicken?” I ask sincerely. “No, penis!” he says with a high-pitched snicker. I can’t tell if he’s joking or not. Then he says, quite seriously, “When one dies, people gonna focus on some work that was so different from the rest and that was it. … A lot of his work has innuendos. Try look. To me, he’s a voyeur. Of course,” he says, reflecting, “I’m reading into it.”

Tsuchidana first encountered Satoru by happenstance on his first day living in New York. “‘You guys was rejected’—that was my opening line to them,” says Tsuchidana, who remembered Satoru’s and sculptor Jerry Okimoto’s names after they had applied for Corcoran Gallery of Art’s biennial exhibition in Washington, D.C., where Tsuchidana had been working as a janitor. “I never did meet them before; I just saw them and felt intuitively that these were the guys—what’s the chance, yeah?” Just as Satoru and Okimoto were about to walk away from the young hassler, Tsuchidana called out, in true local fashion, “‘I know Sugar’—that’s Tadashi Sato—so they came back and said, ‘Oh Sugar, he’s at 109th Street,’” where all the artists were living at the time.

Tsuchidana was the youngest of the bunch. By the time he got to New York to pursue art in 1956, the boys from the Metcalf Chateau were already securing their spots in the art world. Satoru worked tirelessly on the third floor of Dorothea Denslow’s Sculpture Center while gaining prominence through group shows around the city (including a sculpture exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art); in 1963, he was awarded a prestigious Guggenheim Fellowship.

Roving New York with Satoru and the others, Tsuchidana was privy to some of the city’s finest galas, like the opening of the Guggenheim in 1959, and to meeting celebrity collectors like Burgess Meredith, who came to Tadashi Sato’s apartment to look at art. Mostly, though, the lives of the artists comprised of playing cards, drinking from time to time, and talking about anything other than art. “You remember Willie Mays, the baseball player?” Tsuchidana says. “[Satoru] was so intrigued by him.” “Why?” I ask. “Well, because he was the best.” This support system for a bunch of Asian guys from Hawai‘i proved essential for their growth as artists in a place that occasionally alienated them. Periodic bouts of prejudice were combated by potluck dinners with the gang.

Tsuchidana moved back to Hawai‘i in 1959 after receiving the John Hay Whitney fellowship, which granted him $2,500 (roughly $20,000 today) to further his studies in art. By this time, his paintings had evolved from abstract figures to studies in balance inspired by “Mondrian’s horizontal line,” a style he continues today. When Satoru returned to Hawai‘i in 1970, he was a well-established artist. “It was a perfect time for him, just ripe for him to have commissions,” says Tsuchidana, referring to the establishment of the State Foundation on Culture and the Arts and its Art in Public Places program, which dedicated 1 percent of construction costs for new state buildings to the arts. Because of this, Satoru’s sculptures grace many of the state’s most prominent buildings, including Honolulu International Airport, Aloha Stadium, and dozens of public schools and colleges.

Decades later, Satoru and Tsuchidana are still creating work every day; Satoru, grinding and soldering in his garage in Kaimukī; Tsuchidana , up at 3 a.m. to draw and paint at his apartment in Salt Lake, where dozens of large canvases fill one room and what must be tens of thousands of drawings neatly stored in plastic bins and Longs plastic bags fill another. “I always believe that if you create continuously, you evolve. Bumpei Akaji once said to me that I’m producing too much, but I don’t feel that way. The fact that I draw every day—I’m all greased up.” He and Satoru both.

Satoru: The Father

“What he has is something that we all want to be and do, and that’s to be better.” — Gail Goto

“The bridge column, National Geographic, the Smithsonian—he always reads that cover to cover,” Gail Goto, Satoru’s only daughter, tells me from the kitchen of the Kaimukī home she has shared with her father since 1988. “J-dramas—we always watch our J-dramas together.” Around us is evidence of a life spent in support of other artists. Satoru’s work, which overflows from bookshelves and bathroom closets, sits alongside pieces he’s bought from friends (an enormous wood vase by Jerry Okimoto, small ceramic pots by Toshiko Takaezu) and aspiring artists (a portrait of Satoru painted by Kamea Hadar, a trail of ants on canvas by Otto) alike, filling just about every spare space of their home.

Since Satoru was forced to forfeit his driver’s license the previous week, on his 88th birthday, Goto has become the unofficial chauffeur for her dad’s busy schedule, taking him to an art opening at Kapi‘olani Community College’s Koa Gallery, yoga on Thursdays, art drop-offs around town. The relationship between father and daughter has strengthened over the years; Goto remembers growing up as the only child of an artist father, which was like anyone with a parent preoccupied with an all-consuming job would. Even when he wrote letters to his daughter while she was in architecture school, he would sign it, “Satoru.” “I guess he didn’t know his place in my life then. It was just ‘Satoru,’ not ‘Dad.’ … You feel a little shortchanged when you’re younger, but as you get older, you realize that’s why he’s good at what he does, because he devoted all of his effort into doing what makes him what he is.” What he is, Goto realizes now, is kind. “He always thinks about other people. And sometimes that, in my viewpoint, shortchanges him, but from his standpoint, he doesn’t feel like he’s being disadvantaged. He used to tell me, ‘Gail, in life, it’s better to be taken advantage of than to take advantage of people.’”

Her father’s kindness was in no shortage when it came to Ruth, the love of Satoru’s life. The budding romance began while they were attending Art Students League in 1948, and despite being an artist herself, “everything my mom did was in support of my dad,” says Goto. They moved back and forth between New York and Hawai‘i before eventually settling down in a Quonset hut in Mākaha after Satoru received a grant from the Hawai‘i State Foundation on Culture and the Arts in 1970. “My mom said those were the best years of her life,” Goto recalls. “Large acreage, farming, and the outdoors—my mom loved going to Pokai Bay and swimming.” But not soon after they moved, Ruth suffered an aneurysm, then a stroke, and the other debilitating effects that come with trauma to the brain. Now, it was Satoru’s turn to support his wife, which he would do for the next 13 years. “It was really hard on my dad because he was the one solely taking care of her,” says Goto. “I think he really missed her when she got ill and passed on.”

As we talk, Satoru is busy in the garage, working on his latest commission for a residential tower in Kaka‘ako. “All of his art is about growth, the things around us like the moon, the trees, the roots,” says Goto of what she refers to as “additive art.” “It’s about the addition of stuff, reusing and fashioning the drop-offs—what he calls the cutouts—into new sculptures. … What he has is something that we all want to be and do, and that’s to be better.”

Satoru: The Subject

“The piece that Satoru has in his yard,” John Morita begins, referring to a large bronze sculpture originally meant for a Hiroshima memorial. “That is …” he trails off before nodding his head solemnly and giving a thumbs-up. “It’s got all the elements: sophistication, size, significance, all intertwined—friendship,” he says of what he calls one of Satoru’s few political pieces, a departure from his mostly non-controversial subject matter.

Morita, who studied photography and printmaking in San Francisco, knows a thing or two about political art. He spent years documenting the First Palestinian Intifada, an uprising against Israeli occupation in the region, in the 1980s. Mainly though, art to him is about telling a story, a notion he has remained fervently dedicated to regardless of the medium or message. One of his ongoing projects is documenting an artist family in San Francisco—for more than 40 years.

Morita’s fascination with Satoru’s story began in 2008 after he attended a gallery opening Satoru arranged for his friend, the late Jerry Okimoto. He became curious about the kind of person who would be entrusted with the selling of 16 of Okimoto’s ceiling-high wooden sculptures, for which he took no commission. “The family thought Satoru was the only person who could sell it for them,” Morita says. And he did. “The state foundation purchased a couple, the city purchased a couple, his friends purchased a couple—I think he’s got only a few left that haven’t sold.”

Since then, Morita has spent nearly every Saturday for the past six years visiting Satoru’s gallery, capturing the comings and goings of the diverse group of people who pass through. He has trailed Satoru at art openings, award ceremonies, and his home, casually pointing a handheld camcorder in the direction of anyone who might have a provocative clip. The 106-minute rough-cut edit of a documentary is shaky at times, but the picture that emerges in Morita’s years-long slice very clearly portrays a man who cares in earnest about the success of the people around him. In the video, Satoru is seen giving a critique to a young girl’s drawings of elephants, purchasing the work of his mentor Isami Doi, going the extra mile for a friend. “I have to sand about 20 pounds more,” Satoru is seen saying as he grinds away at a 90-pound clam sculpture made by Okimoto. “Lots more grinding to do to get it finished so I can sell it for him.”

Satoru: The Seller

“In terms of sculpture, I’d say Satoru was one of the top three or four to come out of Hawai‘i and just a special human being.” — Walter Dods

Walter Dods, the former chief executive of First Hawaiian Bank, has close to 100 Satoru Abe pieces in his personal collection. This includes one of the artist’s most iconic, which he can enjoy every day: Placed at the crossroads of commerce at the corner of King and Bishop streets, “Eternal Garden,” five large tree-like sculptures fashioned from bronze, sits in front of First Hawaiian Center, where he still has an office with a view. It’s kitty-corner from a piece by Bumpei Akaji and by no accident. Across the street, in Bishop Square, is a work by English sculptor Henry Moore, while another by Bernard Rosenthal stands at the Bank of Hawaii building. “I wanted to get the local boys back in balance,” says Dods.

Despite the many pieces that fill his home and office, as well as the Honolulu Museum of Art partnership gallery in the lobby of First Hawaiian Center, which he established, Dods initially had to be dragged “kicking and screaming” into the art world. “I was a Saint Louis High School grad who had no culture in my background,” says the Kuli‘ou‘ou-raised Dods. But once his friend Wesley Park forced him to take a look, he couldn’t turn his eyes away.

“The work of this group was forged under the stress and fire of the Second World War,” says Dods. “I hope other groups replace them, but it’s hard to find that. … In terms of sculpture, I’d say Satoru was one of the top three or four to come out of Hawai‘i and just a special human being.” For Dods, it’s essential that the arts continue to be supported. “Art and culture is the soul of a community. … You have your social problems—housing and homeless are critical issues—but I don’t see them as mutually exclusive [with art]. … Hawai‘i lacks a vibrant arts and culture community, but what we do have is special, and we need to nurture it.”

Satoru: The Man

Two weeks after Satoru initially declined my interview request, he’s finally ready to talk. “The birth certificate says that I was born 88 years ago, but for me, life started 66 years ago, in 1948, when I said I gon’ be an artist,” he says. “The first 10 years, all struggling. I don’t know what I doing, basically, but lot of emotion in the work. And the composition was poor; the technique and the colors were poor. But after that, one day I realized that I’m very unique, that if I don’t create these things, they’ll never be existing in the world. So that’s the ego that keep me going. Today, I make things without preconceived ideas. I just pick up the metal and wood and start. Along the way, your sensibility comes into play. But when I finish the work, I still surprise myself, and that’s my biggest joy.”

Despite his age, the artist continues to work with vigor. “I think I’m good for two more years,” says Satoru, who long thought he would die at 88, a most auspicious number. “I reach 88, so now I’m getting greedy; I want 90.” With a recently renewed passport good until 2024, Gail suggests her father will be here until he turns 98. “No, no, no, I’m not up for the Guinness World Record. I don’t want my last years to be—” he says, making a choking face. “See for me, if you’re not productive, doesn’t make sense living. … But little secret, I think, is you can almost live as long as you want to. If your mind is there, I think you can.”

Ten years from now, it’s hard to say with certainty what the art scene in Hawai‘i will look like or what legacy Satoru will leave behind. All this is of little importance to Satoru. Despite a lifetime dedicated to the arts, at the end of it all, Satoru wants to be remembered simply “as a good man.” If the last six decades is any indication, when we all look back in the years to come, what we see will be great.