Artists Nanea Lum and Lehuauakea, two creative contemporaries who bring a modern lens to their respective art forms, discuss kapa making, colonial institutions, and the hard-bitten truths of being a contemporary Kanaka Maoli artist in Hawai‘i.

“The Western concept of art is not really translatable into the Hawaiian ideal or identity,” says the kapa artist Nanea Lum. She appears as a floating head in my computer monitor. Next to her on screen, Lehuauakea, a contemporary of Lum, nods emphatically within their own virtual square on Zoom.

The two are thousands of miles apart — Lehuauakea resides in Oregon, Nanea lives in Hawai‘i. Yet, as Kānaka artists, their paths are constantly converging. At present, the topic: breaking down the differences between Western versus Native Hawaiian notions of artmaking. While the subject reads didactic, their first-hand experiences ground it in something urgent. Their discussions often straddle this line, pedagogical themes steeped in real-world relevance.

Their art, too, straddles binaries: traditional practices worked within modern-day contexts; contemporary narratives told through multigenerational stories; and reexamining institutions while existing within them. It is a liminal space within which Indigenous artists often find themselves, particularly as they work through the artworld. Here, Lehuauakea and Nanea discuss the complexities, dualities, and realities of being a contemporary Kanaka artist today. —Eunica Escalante

Nanea Lum. Image by Kara Akiyama.

Lehuahuakea. Image by Moriel O’ Connor

Nanea Lum In Hawai‘i, as a Hawaiian artist, I’m still having to support myself by working night time jobs just to pay my everyday bills or even to start paying back my student loan.

The unfortunate circumstance in Hawai‘i is that Hawaiian fine artists are largely unsupported by industry benefactors, creating an inauthentic market for art here. The creative industry in Hawai‘i is bottom-line limited; increasing the value of your work is limited to who is made aware of its importance.

As much work as I do as an artist in the community, working for a nonprofit like the Hawai‘i Arts Alliance or as a teacher, it’s still not enough to give me consistency and security. So, I have to put myself in the line of fire during this pandemic. I have to go to work every night and talk to tourists — be a “good person” of this place by hosting others.

I’m not going to lie, sometimes I think about where you’re at in Portland, Oregon, where there is an Indigenous community with more support for the arts. Diaspora is still a state of being Hawaiian, one that so many of us have to navigate. I really admire the way that you’ve stood your ground as a Hawaiian artist, but getting to be with other, more supportive communities.

Diaspora, it is what it is. It doesn’t make you any less Kanaka or Indigenous. It just means that you’re being those embodiments of your identity somewhere else.

Lehuauakea

Lehuauakea It’s been a lifeline for me. It’s not just Native Hawaiian support up here. It’s not even just Pasifika support. It’s an Indigenous community as a whole that has really floated me the whole time that I’ve been up here, especially during the pandemic.

I was talking to my grandma the other day, and she was giving me a hard time for not moving back—she was just joking because, you know, grandmas. I told her that I’ve been trying to move back ever since I graduated college. That was the plan. But then work kept coming in for me here, opportunities for my career and what I had gone to school for—which is not always the case for everyone, especially in the arts.

It makes it more complicated to have roots in so many places. My heart and my spirit is back home on the Hāmākua coast. And my financial security is here, in this completely different place that’s over 2,000 miles away. Eventually, I do want to move back. But it’s all contingent on my financial security, when it’s feasible.

Diaspora, it is what it is. It doesn’t make you any less Kanaka or Indigenous. It just means that you’re being those embodiments of your identity somewhere else. I think that’s the story for an increasing number of us these days. A huge reason I do what I do is to encourage people like me, who have split stories, to keep going and to connect in whatever ways that they can.

If I can provide that connection, through workshops or showing my work and creating spaces for other people to do the same, that’s how I can contribute. But it hasn’t always been easy for me. There are tons of times where I felt lesser than, you know?

Aloha ‘Āina is the resistance from inside all of us—to keep expressing our vitality, loving our life, water, and land.

Nanea Lum

NL Yeah, and I think that that’s kind of consumerism we are all living through now, right? The discourse of our art goes onto an online market for consumers, they either want it and need it right away, or they just say, “That’s nice,” and keep scrolling.

This discussion we’re having about contemporary art is about guiding people towards how they can spend more time looking at Hawaiian contemporary art rather than just being like, “Oh, can I consume it? Can I go to Hawai‘i, put it in my portfolio of life experiences, and then just back go home?” Sometimes people want things so immediately.

Really, we’re cultural leaders as contemporary Hawaiian artists. We’re looking at philosophy and culture and how those things inspire us to keep innovating.

As I have been coordinating the Grric Contemporary Gallery at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, I’ve collected perspectives about this contemporary art market from the artists themselves on contemporary art in Hawai‘i— which is very different from contemporary Hawaiian art. I’m asking questions like: “How do you describe your creativity? How is our Hawaiian art a part of ‘āina? How does it fit into the context of Aloha ‘Āina?”

All of their answers explained that Aloha ‘Āina is the resistance from inside all of us—to keep expressing our vitality, loving our life, water, and land despite its improper use and it being illegally occupied by the federal government of the United States. We’re all just being forced into the machine, right? But there’s still these people who live resistance and who breathe new meaning into our ‘Ōlelo Hawai‘i.

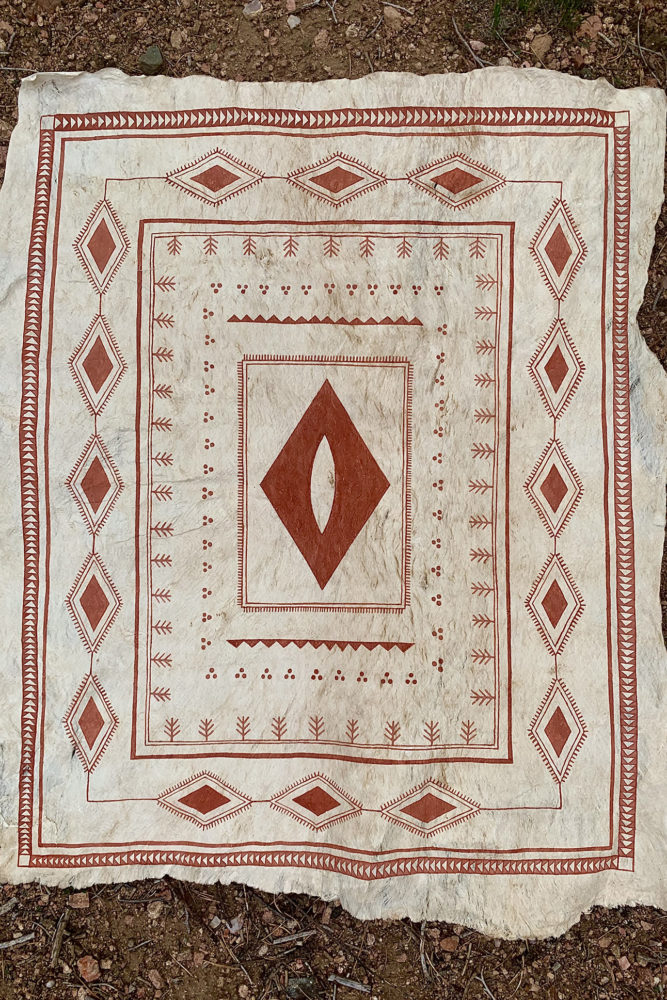

I mean, kapa work, right? Being a kapa artist, you’re really using the symbols of old and the language that the materials give us to be in context with our kūpuna long past.

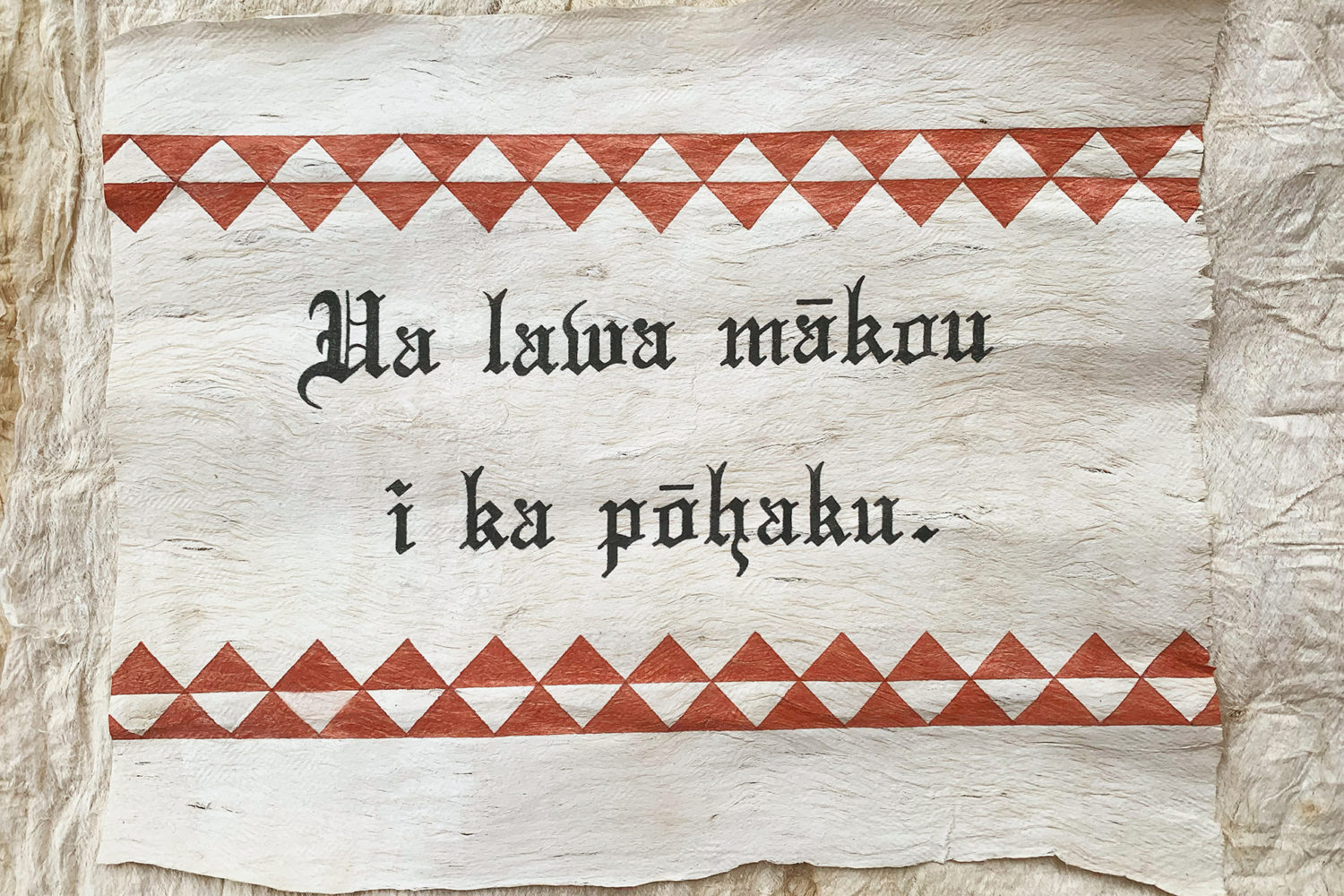

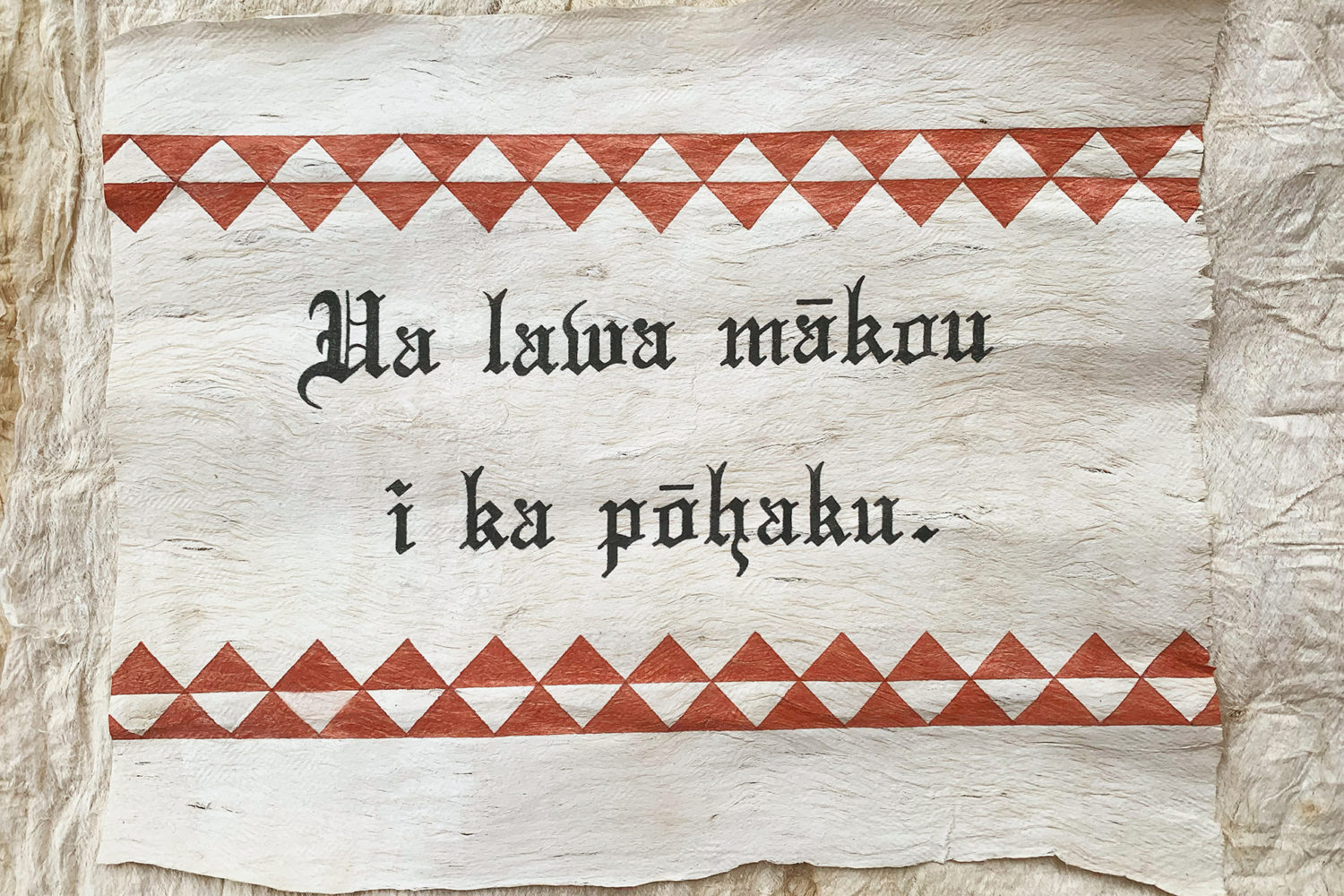

Nanea Lum for her Single Double residency.

Courtesy of the artist.

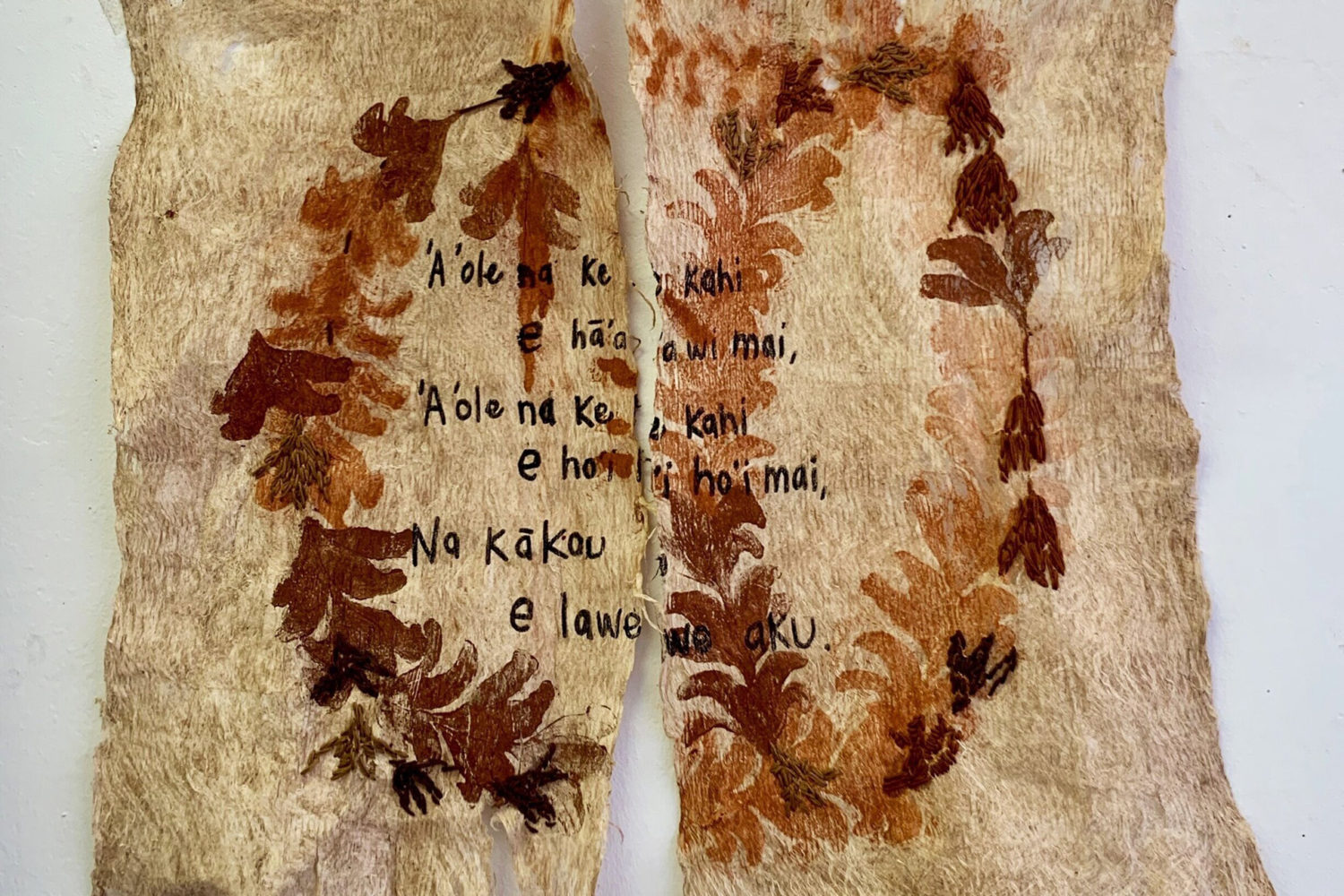

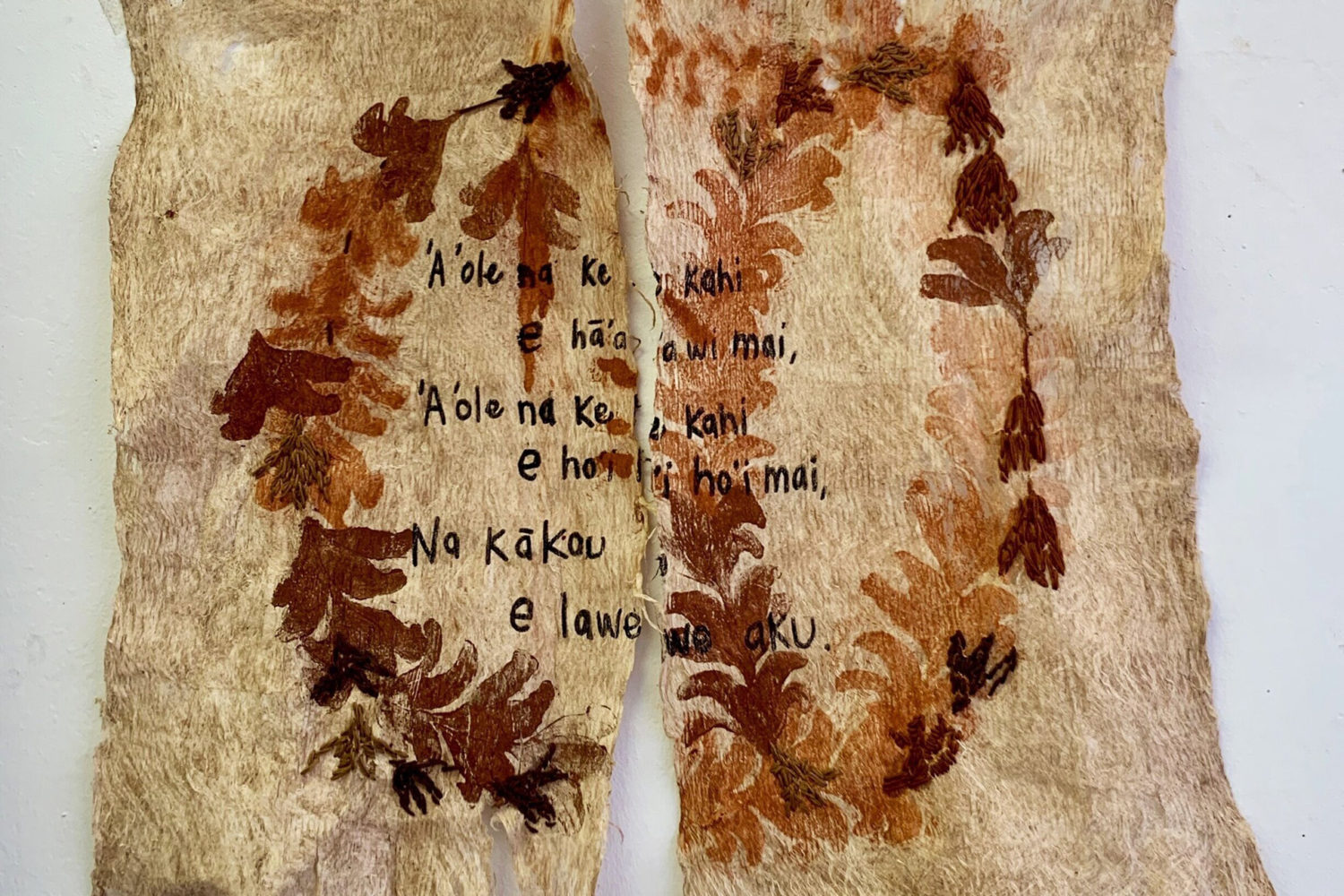

Lehuauakea beating kapa.

Image by Garrett Vreeland.

L I was talking to Uncle Tom, who you probably follow, @homaikapono on Instagram?

NL Yes!

L Super cool uncle, super ‘olu‘olu vibes. But he asked me to be a part of this hui for the next year, focusing on mahina (moon) cycles and situating yourself within time and place according to what’s in the sky. He was talking specifically about kapa makers, who he believes are critical to the revival and reclamation and resilience of the Hawaiian people.

Kapa making includes one of those non-mediated rhythms, similar to kākau. That tap, tap, tap, tap. It’s one of those ancestral rhythms that still flows unmediated from thousands of years ago. And not only that, it’s also a flow in the rhythms of ‘āina, of the mahina cycles, and how to do that work within a certain context of place and time.

I never really thought about it like that. Kapa makers are so important. We are, like you said, in touch with putting ourselves in the company of our kupuna, their form of communication and telling stories. But we’re also creating new stories and new ways to tell those stories using new patterns, new ways of working with this material.

Then, I think about the others who are part of this growing force of resistance and resilience. It’s not just kapa makers. There are other artists, activists, and community members. There’s not just one textbook way of engaging. We need that diversity in our approach because that’s the resilience. It’s that varied approach that creates a strength between everyone who is involved.

Being a kapa artist, you’re really using the symbols of old and the language that the materials give us to be in context with our kūpuna long past.

Nanea Lum

NL Exactly, those are the discussions that need a longer look. I’ve asked other creators too — those who refuse the title of artist because it denotes too much societal privilege — how can art made by a Hawaiian person transcend Aloha ‘Āina. And their answers really draw back to those two realms that you just spoke about.

Some people talk specifically about getting into the wā, that unmediated rhythm. Their art is really tapping into that Hawaiian methodology: a heritage of aesthetic that considers the wā ma mua, the time before us. This way of knowing the world comes from a familial relationship to ‘āina. Retelling the nature of this relationship is what being a Hawaiian artist is about: being able to work towards a hana no‘eau.

Then there’s also, like you said, those mahi‘ai people who are influenced by living resistance. These aloha ‘āina activists use a different Hawaiian methodology: a responsibility of building and protecting relationships, to repair the past, and to see into the future. These artists activate earth, and display knowledge coming from their experience of the ‘āina.

I guess what I’m doing from my critical lens as a Hawaiian artist is to make it explicit that those people are still contemporary artists like I am. Even though they’re only carrying pōhaku to rebuild our fish ponds, I really see them as an artist because of the wā that they tap into in order to create. Like us, they really understand how to process material. Their work is still a kind of art even in this contemporary time.

There are all of these examples through time and history that tell us what art is. We in Hawai‘i don’t have that same history for our people to tell us what our version of contemporary art is.

We are still treated as the token in a lot of spaces. We’re seen as the other or labeled as ‘the Native artist’—not just as artists. There’s always going to be that inherent distinctive label put on it.

Lehuauakea

L You bring up a good point because the word artist is not our word. We never really had a word that directly translates to the English artist.

NL Hana no‘eau. That was one answer from Nālamakūikapō Ahsing. He says that the Western concept of art is not really translatable into the Hawaiian ideal or identity. Instead, we think of our creation as these hana no‘eau: methods that teach lessons, define talents or instill a knowledge pathway.

L That’s good. For me, that’s the closest translation or bridge-crossing term that I can think of: creation or creative. It speaks more towards the Hawaiian understanding of where all this is coming from. It becomes shallow when you think of it in a Western art context. But, for a lot of, if not most, Hawaiian artists nowadays, creation can mean tapping into something deeper.

It’s the creation of Pele, the force behind her energy to create entirely new land masses. Or the power of creation held within a seed versus just taking a brush and splattering some paint on a canvas. They both have elements of creativity, but one is rooted in something deeper, something intergenerational and spiritual. And I think that’s what makes a lot of Indigenous art rooted in something that transcends time. That’s where a lot of the power comes from.

NL One issue, too, is that Indigenous creation is outside the scope of the Christian concept of creation. And so most audiences come with a personal baggage towards creation and creativity because they usually view it from a myopic, Western lens rather than something that is truly generative. We both went to art school, and we had to deal with that a lot. People would usually take our stories for granted because not everybody has the same level of deepness to their roots.

I hope that our audiences can start to see the world not just though how they were raised, but through the fact that they can learn from other peoples’ stories.

Retelling the nature of this relationship is what being a Hawaiian artist is about: being able to work towards a hana no‘eau.

Nanea Lum

L A lot of our non-Hawaiian audiences are starting to shift their appreciation for works that are created beyond the context of their own worldview. Just in my experience, there has been more open-mindedness for contemporary Native artists and what they’re contributing, what they have historically gone through and how that resilience plays out in the context of their own work.

On the other hand, it’s something that we always have to deal with. At this point in time, we are still treated as the token in a lot of spaces. We’re seen as the other or labeled as “the Native artist” — not just as artists. There’s always going to be that inherent distinctive label put on it.

I’m not necessarily saying that’s always bad. But it does at times put you in a pigeonhole, where you’re expected to deliver some extravagant, often exotic package. Especially being from the islands, viewers often expect a certain level of performative experience from us.

A lot of the work that I’ve been doing lately is saying fuck you to that. Fuck your expectations. Fuck your postcard images of what you expect my ancestral islands and culture to be. This is how I’m showing up now, and you guys need to wake up to that. Part of that for me is not providing translations for the titles of my pieces. I used to, but in the last year or so I’ve stopped. And that goes back to the colonization of Hawai‘i and how our language was stripped away from our families and our kids. We’re only now starting to really get that momentum back.

As a Hawaiian artist it’s deciding what you want to share. Is it going to benefit your community, your family, and you as the creator? Or is it just going to be appropriated instead of appreciated? Doing this kind of work you walk a really narrow line straddling these two fields.

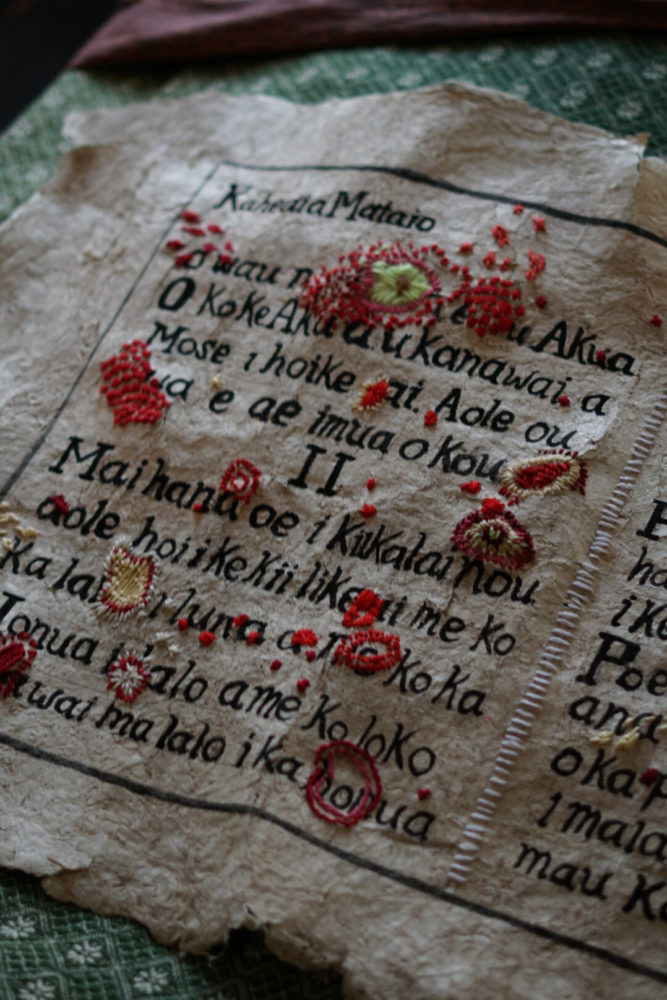

“O Haumea Kino Pāhaʻohaʻo” by Lehuauakea

“ka ‘ōlelo o ke Akua” by Nanea Lum.

NL That’s really great that the museum structure can appreciate your work and start to show it to an audience whose worldview you can really influence.

In 2021, you came and saw my thesis show Eia Ke Kumu. There was no kapa on the walls, but kapa being made in the room. And that was my insistence because a lot of our institutions, like museums, will take kapa made by contemporary makers but appreciate it only as an Indigenous story. Yet, we know that there’s more to the work than just the final piece.

My kumu Verna Takashima, she makes kapa so rigorously and at such scale. She lives in Papakōlea, she has a haumāna. She inhabits these very spiritual places, and all of that is connected to her art practice completely. Yet the museums and institutions here are still only interested in the final product, in the kapa moe itself. Which is cool, we need our kapa moe to be shown in museums, especially as a representation of Hawaiian culture. But there should be more focus on our makers and the process of making because that is going to help bridge the gap between appropriation and appreciation.

You can look at a finished kapa and marvel at how wonderful it is. But if you haven’t seen the hard labor that went into making it, then you might not fully understand how special it is. So, I’ve been making a lot of videos and installing them in galleries or physically going to galleries to make sounds with my tools. I’ve began beating kapa there so that that the audience can understand that this is not just about the finished projects. This is about living our resistance, making and tapping into the wā as often as we can.

L It’s like looking at the tip of the iceberg without seeing the huge, massive resistance that lies underneath the surface. That’s language reclamation. That’s land reclamation. That’s understanding the roles and the cycles of the plants that we use for the dye, the beating.

NL The water.

L Totally, which is a huge issue for native people right now, not just Kānaka. As artists, it’s in our nature to recognize these things because we’re in it. We’re in the process, we cannot make kapa by just doing one part. You have got to commit to the whole thing. And once you start doing one part, you realize, “Oh, I got six other parts I’ve got to learn.” And the journey never stops.

It’s not going to happen in one generation. We’re undoing generations of these systemic obstacles that were established by foreigners to keep us down, to force us to assimilate, to claim that we’re not beneficial to ourselves or our culture or our ‘āina. And whether we’re doing that back home or for our diasporic communities abroad, I think that still carries just the same amount of weight.

Kapa making includes one of those non-mediated rhythms, similar to kākau. That tap, tap, tap, tap. It’s one of those ancestral rhythms that still flows unmediated from thousands of years ago.

Lehuauakea

NL That’s beautifully said. We’re really making sure that the next generation doesn’t have all the same obstacles as us because we did the work to free up the language. That was what my whole thesis was about, freeing up the language.

But also in these spaces, we need to make room for unapologetic Hawaiians like you who don’t need to translate. They are speaking to their audience. They’re speaking to their hoa ‘āina. Why should there be translations involved here?

L Yeah, I think it’s important to for us to be unapologetic. We’ve been born into this culture that really was trained to cater to haole or to foreigners, to make our culture palatable to them, to make it sellable. If we’re too-this or too-that, we feel the need to apologize or to tone it down. Where I’m at in my work and in my own personal growth as an individual, I’m just like, enough already. We’ve spent our whole lives being that way. And not just us — our kūpuna and their kūpuna too — everyone was toning it down to make other people comfortable.

NL Or were they being clever? The act of subversion and of being subversive is a concept that often feels elusive to me, but I think it is so important. On one hand, you can try to erase the meaning of an artist’s work. But on the other hand, they’re going to keep creating and subverting the white dominance of everything.

At the end of the day, if our hoa ‘āina are the only ones who understand us, then we won. We did exactly what we were trying to do. Our art is not for the masses. It is for awakening of our Indigenous community and for decolonization. Our people have all met us at that mana and we continue to create.

L Yes, real mana recognizes real mana. If people cannot understand our art — if they cannot hold a tree and feel water — then they haven’t done the work yet. And that doesn’t mean that they’re not going to, but that they have not been immersed in the kind of mana that it takes to recognize that deeper relationship.

It is about decolonizing our relationships to ourselves, to each other, to all the things that go into whatever it is we’re doing. And it goes back to the importance of finding solidarity with other Native people who are not just from our community, not just from Pacific Islander labels, but Indigenous people as a whole. We’re all very different, but there’s a lot of similarities between our cultures.

It makes the work even more powerful. I feel more affirmed and that what I’m doing is bigger than myself. I know that we’re not alone in what we’re doing or what we faced historically. That kind of solidarity expands generations.

Real mana recognizes real mana. If people cannot understand our art — if they cannot hold a tree and feel water — then they haven’t done the work yet.

Lehuauakea

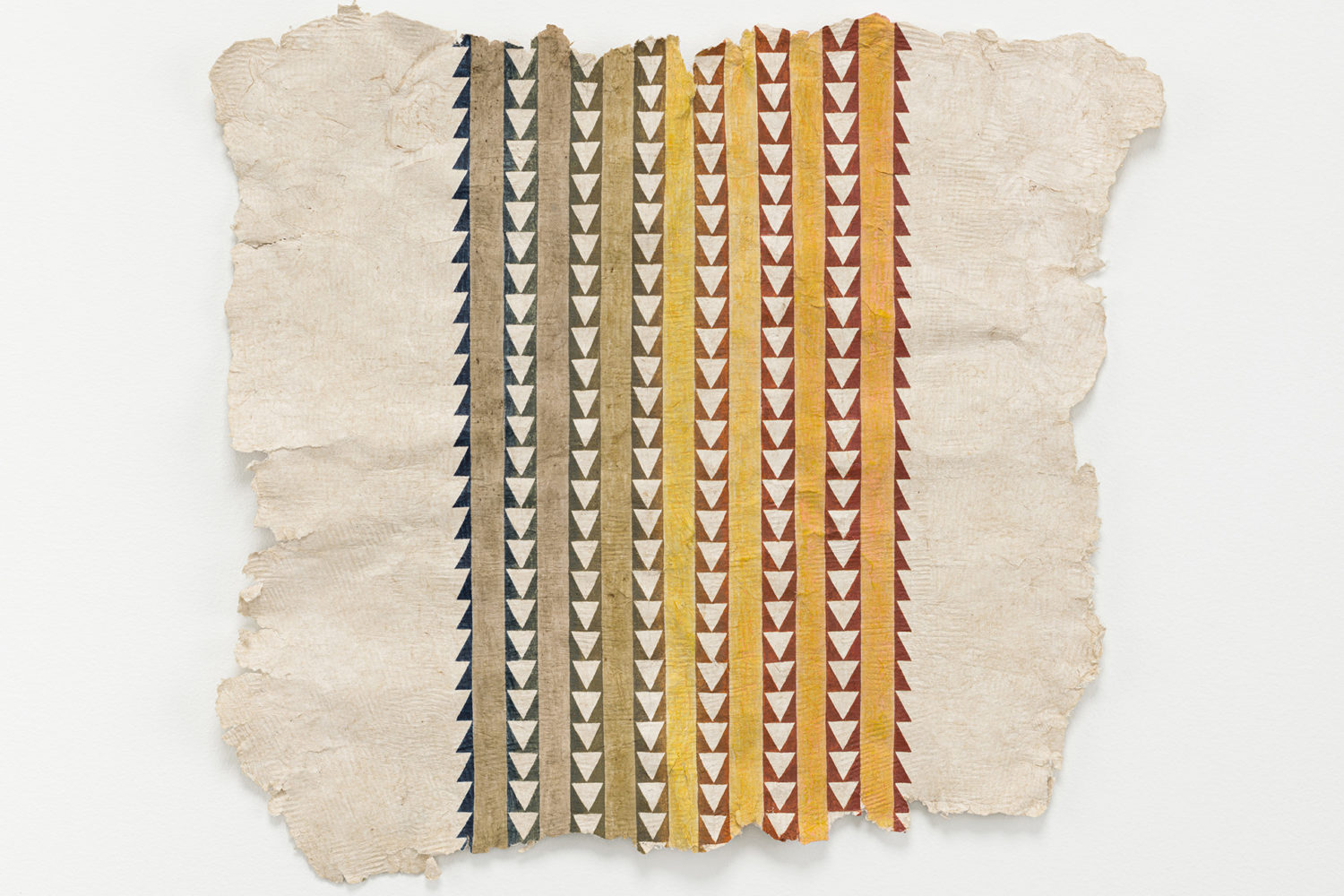

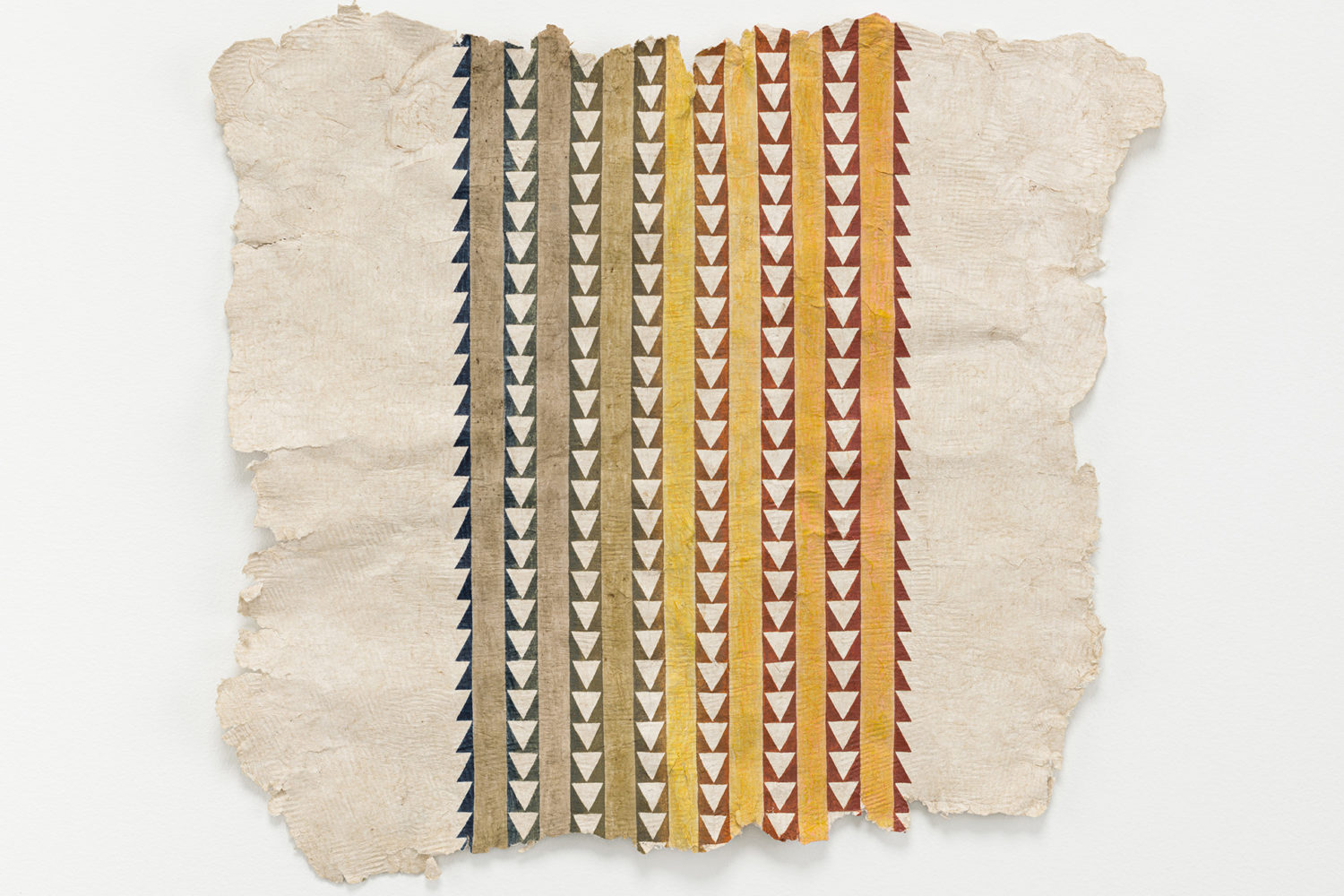

NL I’m looking at the photos that we chose for our Zoom backgrounds. It’s really amazing how we both have versions of our kapa behind us. I think discussing them would be the perfect way to cllose this conversation for Flux.

The kapa you’re showcasing embodies that material kapa, the symbols and patternology of our kūpuna in order to navigate the surface for yourself. Am I right?

L Yes, exactly.

NL I love that. Now, you go for me. What’s my kapa doing for me?

L To put it simply, your kapa is getting down and dirty with it. It embodies actually, literally going to the roots. And I think that’s super important for kapa makers to know where their trees are coming from and to have access to that. As soon as you put up this photo of your painting, there was this instant recognition. The way you captured the light going through the wauke leaves, it’s spot on.

NL Yes — I’m really using painting to relive all the things that kapa teaches me. Making kapa, it enhances my life in such profound ways that I have to paint what those changes are. There’s these moments during the creative process where I think, “This is where I want to stay. Stop time forever and just leave me right here.” Those are the moments that I try to translate so that people can understand why we love making kapa so much.

L And it’s hard to translate with words. In fact, it’s impossible. When I’m getting into the zone and beating, that rhythm is just like my heartbeat. It takes me out of the physical form. It stops time. Ultimately, that carries into the finished piece itself. If people are open to receiving that, they’ll see it.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.