Hawai‘i creative folk are drawn to the historic Johnson house. For Brennen Cunningham, the residence’s lasting nature presents reminders to elevate one’s design practices.

Images by Viola Gaskell

Since early 2022, woodworker Brennen Cunningham and creative producer Hannah May have been residing in a historic home perched among the treetops of Mānoa Valley’s ‘ewa slopes. Situated at the end of a steep path composed of approximately 84 lava rock steps, the house presents an unassuming exterior which shelters a warm, monastic Japanese-inspired home. Built in 1938, the residence, colloquially called the Johnson house, a reference to the esteemed Hawai‘i architect Allen R. Johnson who initially built it as his personal home, is an ode to the Oʻahu outdoors and to the refined simplicity of Japanese architectural design. The structure’s uninterrupted planes reach out towards Lēʻahi and the sea beyond, separated only by screen and redwood framing.

For Cunningham, living in the Johnson house gives a sensation of physical and mental spaciousness, while also serving as a reminder to keep the standards of his own woodworking craft high. “As a woodworker, it’s really inspiring on a daily basis to live in a nearly 100-year old home filled with detailed carpentry that still functions perfectly,” he says.

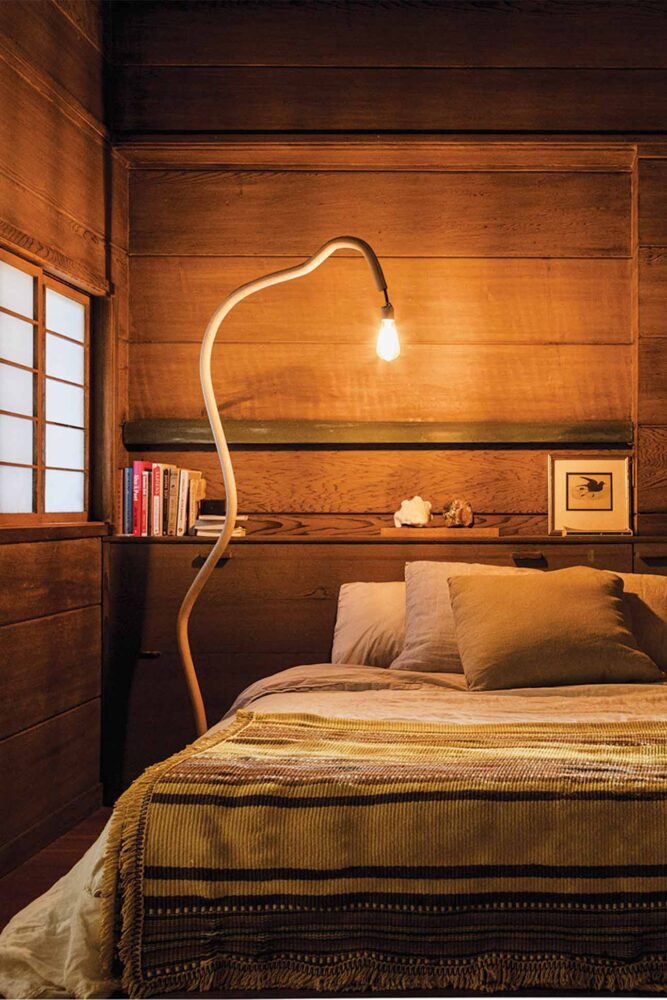

Like much of the furniture that Cunningham builds, the house he resides in is linear in nature, shaped by hard edges and clean lines. But it is his signature curved lamps that usher an organic playfulness into the space, for example, the original prototype which resembles an ‘S’ reaching out towards its cohabitants. In 2019, Cunningham began designing the distinctive lamps, which became the namesake of his company, Good Lamp. Last winter, lamps came to the forefront of his work during a residency at Single Double, the boutique-cum-art space in Honolulu’s Chinatown, where he experimented with new materials and shapes to create a line of shorter acrylic lamps that complement his tall curvaceous ones.

Drawing inspiration from traditional wooden boat builders who would use steam to bend the hulls of ships, along with techniques used by Indonesian rattan furniture makers, Cunningham created his own method for bending the same pliable wood. His method materialized as a board, taller than he, covered with holes of varying size used to hold moveable dowels that he bends steaming rattan poles around, securing them until their shape solidifies. The board’s modular form enables him to create curves of varying sizes and intensity, a process that renders each lamp one of a kind. For Cunningham, the arcs of his lamps are a nod to nature. “Curved shapes appeal to the ancestrally connected part of us,” he suggests, and “in a way that comforts your subconscious by adding an organic element to what is mostly a manufactured, rectangular, straight space.”

Growing up in upcountry Maui, Cunningham, age 33, gained his foundation in carpentry by spending summers building houses and furniture with his dad, Bill. The elder Cunningham’s craftsman’s approach left an impression on his son; Cunningham readily brings to mind the elegant spiral staircases with broad handrails and detailed grain-matched cabinets his dad built. While studying science at University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, Cunningham became engrossed in photography. He went on to work as a photo assistant in San Francisco and New York, until he felt called back to work with wood again. For a year, he worked at the New York fabrication studio Friends and Family where he built out interiors for brands like Outdoor Voices and Everlane. In 2018, he returned to the Bay Area and started designing and building custom dining tables, bed frames, and desks, along with interior projects on his own, including a handsome, slatted wood bungalow and listening lounge for the tasting room at Juneshine, a hard kombucha company, in San Diego.

He and his partner, May, who grew up in Hilo, were debating whether to move back to Maui or Hawai‘i Island when they learned that their friends were moving out of the Johnson house, and it would soon be up for rent. And, so, Cunningham and May officially moved into this “house without walls,” as Graham Hart, the Honolulu architect and co-founder of Kokomo Studio, describes the dwelling. Hart says he has known the various tenants of the Johnson house for over a decade, and they’ve all been creatives: first his classmate in architecture school; next, a pair of designers; then, Cunningham and May, who is a creative producer for Instagram. “It seemed like too good of an opportunity to pass up,” says Cunningham.

As a woodworker, it’s really inspiring on a daily basis to live in a nearly 100-year old home filled with detailed carpentry that still functions perfectly.

Brennen Cunningham

While many modern and Japanese-style homes were built during the postwar era, the Johnson house is a rare example of authentic Japanese architecture in Hawaiʻi built before 1939, according to Hart. Johnson and his partner, Thomas Perkins, who built his own home next door, came to Oʻahu in the mid-1930s at the behest of their contemporary, Vladimir Ossipoff. Hart says that the majority of Johnson & Perkins’ residential designs are larger iterations of the Johnson house: screened-in engawa decks, deep overhangs, and shoji panels to separate spaces. Johnson learned carpentry from local craftsmen originally from the Japanese archipelago. Cunningham supposes these craftsmen were responsible for the more unique details strewn throughout the house; for instance, the use of bamboo (which resemble ʻopihi stamps) as door handles on the shoji panels that separate the bedroom from the living room.

Despite the mist that sometimes drifts in from the screen-enclosed, engawa-style wraparound deck, the house is remarkably well-preserved. Cunningham attributes the Johnson house’s resilience, in part, to the woods used for its creation: redwood, mahogany, and Douglas fir. “Each brings their own sense of warmth and durability,” he says, the latter proven by remaining intact for 85 years. Ultimately, it’s the spirit and ethos of the house which endures, according to May, as a “living, breathing space that welcomes all life forms.” The generous rains and the howling winds that rip down and through Mānoa Valley to grace the home are a testament to this. “The geckos really own this house, honestly,” she says. “We are just visitors. You can’t be precious about everything in this house, you just be the best steward you can.”

HOW TO LIGHT YOUR LIVING SPACE

Here are some tried-and-true tricks of the trade that will enliven any room, according to Brennen Cunningham.

1. Think beyond overhead lighting.

Many modern homes are over-reliant on central overhead lighting, but research shows lighting like this has its drawbacks for sleep. Instead, arrange an assortment of lamps to create a warmer atmosphere.

2. Tuck lamps into corners to expand your space.

Lighting corners, or otherwise “dead” space, can bring dimension to a room.

3. Use a warmer bulb in your lamps to make a space feel more cozy and intimate.

Good Lamp’s light bulbs are 2,100 kelvin LEDs.

4. Balance indoor and outdoor light.

For instance, when the sun is setting the lights can be weighted towards the side of the room the receives less natural light.

Learn more about Good Lamp Co. at

good-lamp.co.