From modest food forests to worm composting, Mā‘ona Community Garden’s hardscrabble efforts take a sustainable stand on Hawai‘i Island.

The 5.4 acres in South Kona where Hawai‘i Island’s first community garden now sits was once a virtual wasteland, degraded by years of neglect and illegal dumping. As a little girl, Chantal Chung would visit a beautiful botanical garden in the very same spot. In 2007, Chung was recruited to help set up a nonprofit that planned to build a multimillion-dollar civic center on the Kamehameha Schools-leased land. “I just had a nagging feeling that it should be something else, something better,” she says.

At the time, Chung was working as an Ohana Advocate for Keiki Steps, a Hawaiian culture-based preschool, where she and another mother had recently planted a 3 feet long, raised garden bed that successfully grew corn and bell pepper. “It’s down closer to the ocean so we really felt like we accomplished something,” she says.

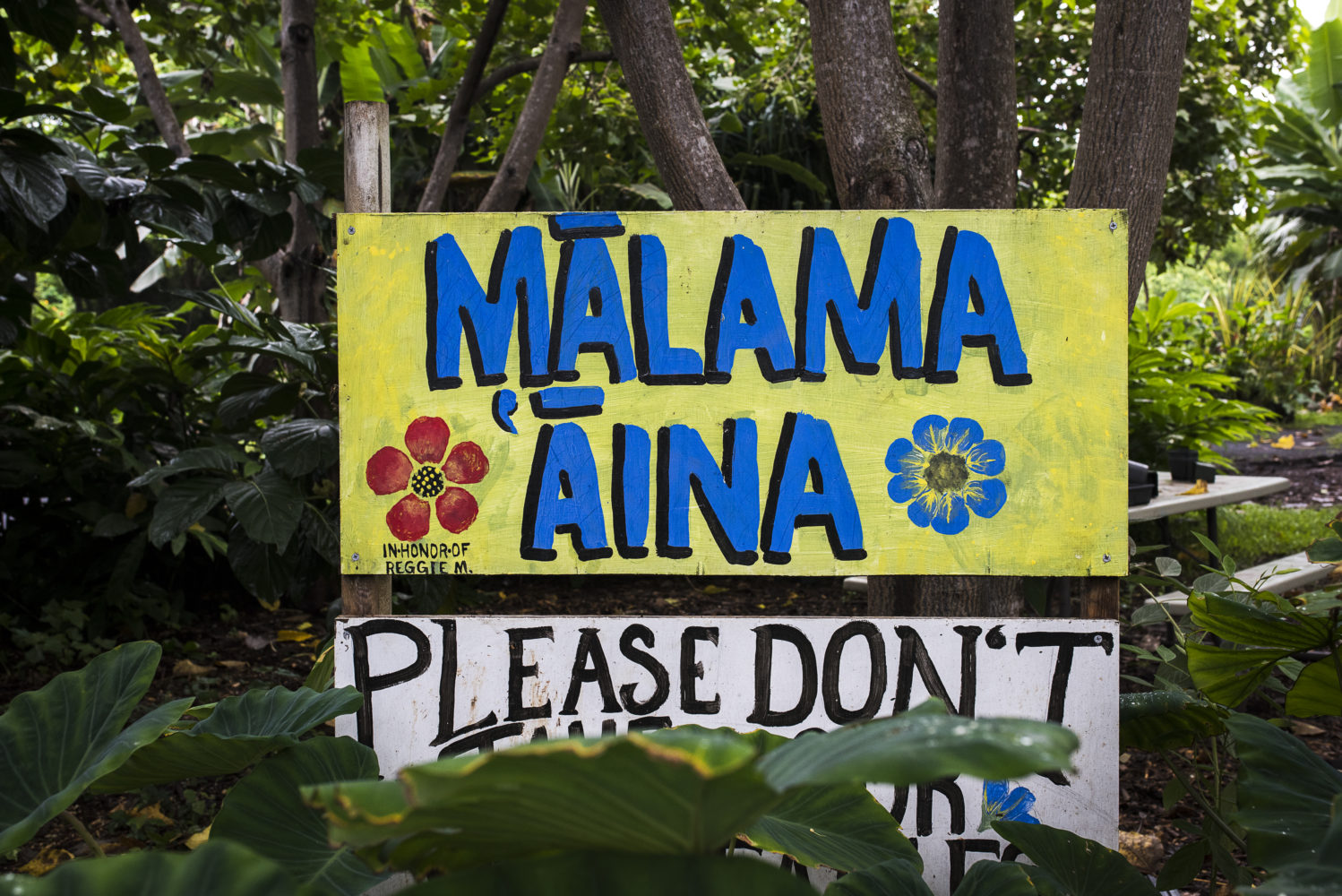

In a twist of fate, several investors backed out of the civic center project when the 2008 recession hit, and Chung set a new plan in motion for a communal garden space that could host farming and conservation ventures. With her longtime friends Lovey Simmons and Hala Medeiros, the trio founded Mā‘ona Community Garden, named for the Hawaiian word meaning “full or satisfied after eating.” By growing nutrient-dense, locally grown food through sustainable techniques, they hoped to encourage better physical and mental health among local families, especially Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islanders affected by chronic disease, and spark cultural connection and entrepreneurship in the process.

But, it would take a laborious grassroots effort to realize their vision. In the four years it took to transform the grounds into arable land, volunteers removed 55 tons of rubbish, and recycled and composted much of it. Neighbors offered hauling services, and donated excavator and backhoe equipment. “My friends and I were stripping copper in the bushes,” Chung recalls, “that’s how we made our first few hundred dollars to put gas in the machines and purchase large containers to take away what we couldn’t compost.”

With help from community partners and grants, they planted breadfruit trees and taro, and experimented with composting methods. One of the acres became an experimental food forest and fruit germplasm repository, a valuable resource for Hawaii Tropical Fruit Growers to store and study fruit seeds and genetic material. After six years of groundwork, the garden officially opened to the public in 2014.

We want to give people permission to look around at their community and ask, ‘How can we do better with what we have?’ Because no one is more powerful than you and I.

Chantal Chung

Then, in 2016, the garden began the Community Composting Project with Hawaii ‘Ulu Producers Cooperative. Unable to find vermicasting systems, a method of using earthworms to process organic waste, in the United States for less than $10,000, Chung replicated a model from India that cost $500 to build. The 40-by-4-feet bin is populated with Indian blue worms working around the clock to turn thousands of pounds of food and paper waste into organic fertilizer with no effluent or air pollution. “These worms have great power,” Chung says. “They eat waste products and output gold!” Sprinkling a single cup of the vermicast around the base of a fruit tree will inoculate the soil around the tree’s entirety. The composting project has been so successful, the garden is now able to offer its worm-made fertilizer to schools and organizations free of charge, and to farmers and gardeners by donation.

In 2021, the garden completed an expanded aquaponics system, comprising four grow areas inside a 3,500-gallon tank. Thanks to the off-grid water catchment and a solar-powered ebb-and-flow pump setup, the closed loop system sustains plants and fish using less water and space than traditional soil gardening techniques. Food plants such as watercress and ong choi thrive next to swimming guppies, which will soon be replaced by awa, ‘ama‘ama, and other fish traditionally farmed by Native Hawaiians.

Currently, Mā‘ona Community Garden offers family and individual garden plots, growing and composting workshops, food plant giveaways and volunteer workdays. They host a monthly Community Cardboard Shredding Day, where residents can bring in their boxes or pick up freshly shredded cardboard to feed their compost. Plans for expansion include adding two additional worm bins, upgrading the solar electrical system, and building a certified kitchen with attached farmers market, expected to break ground in late 2022.

A goal is to eventually get the community garden’s composting and aquaponics models to turn a profit and create living wage jobs. Chung hopes to empower Hawai‘i residents to create their own sustainable, economically viable solutions to environmental and social challenges. “The idea is to get the template of problem solving out there,” she says. “We want to give people permission to look around at their community and ask, ‘How can we do better with what we have?’ Because no one is more powerful than you and I.”