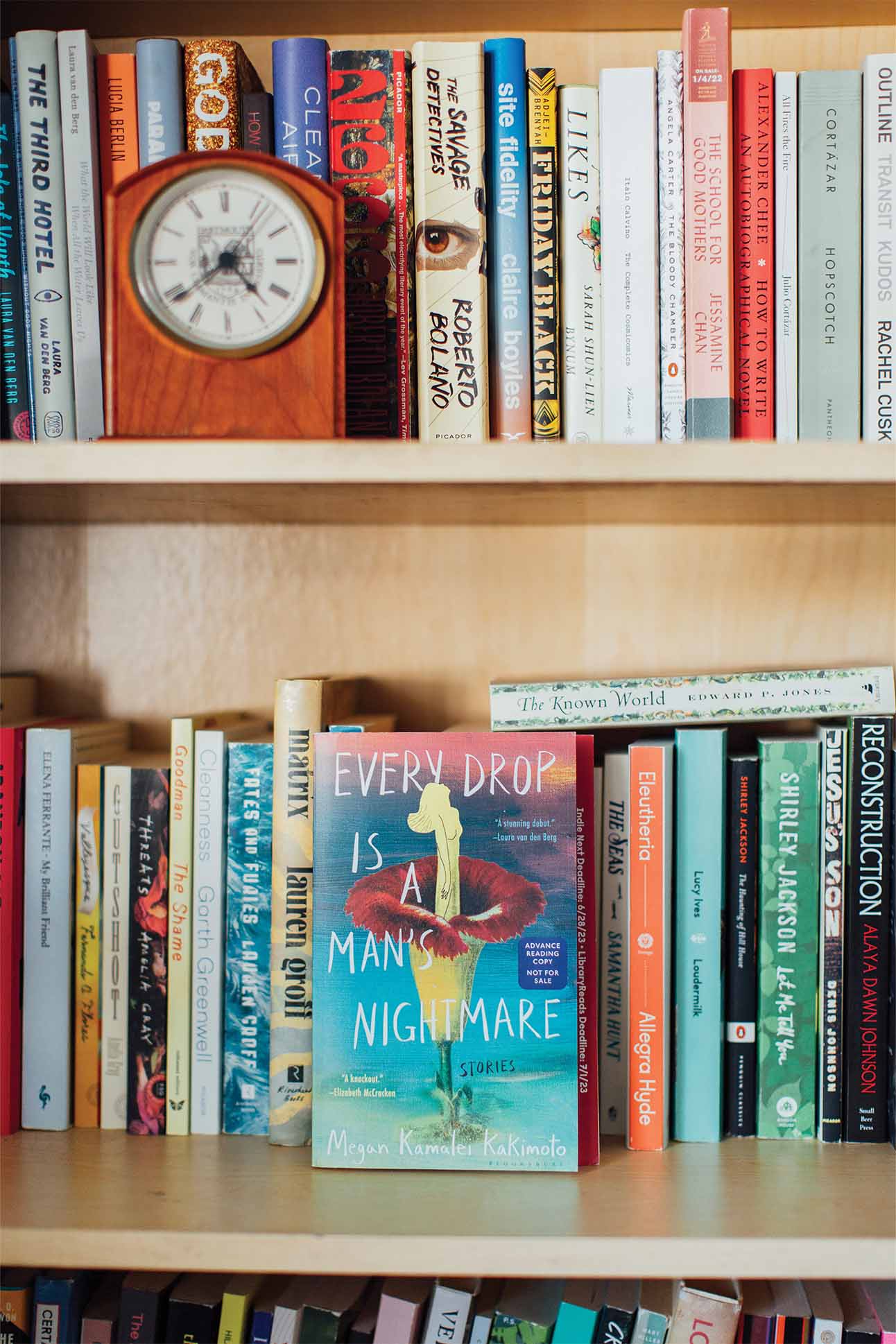

Megan Kamalei Kakimoto embraces the macabre and ghostly side of Hawai‘i in her debut short story collection.

Images by Meagan Suzuki

A thrilling examination of the psyches of Native Hawaiian women, Megan Kamalei Kakimoto’s debut collection of eleven short stories Every Drop is a Man’s Nightmare is as haunting and titillating as its title suggests. The Hawaiian Japanese writer from Honolulu muses on ancient moʻolelo and a tragic history of colonization and exploitation, in order to conjure a present-day Hawaiʻi where cunning menehune appear on one’s doorstep, military strikes shower the island of Kauaʻi, deadly night marchers are summoned through kapu words, and bringing pork down Old Pali Road has dire, atavistic consequences.

The collection drastically veers from popular literature about the islands, which tend to set their narratives against a soothing tropical background. Kakimoto, however, prioritizes penetrating the intimate lives and troubled minds of her characters as they contend with motherhood, lust, ambition, and grief. Kakimoto’s women aren’t mad, but they aren’t “all right” either. The stories that result are unsettling, touching, absurd, and humorous, an ode to the complexities of Hawaiian femininity.

Despite the book’s serious subject matter, Kakimoto herself is naturally lighthearted and joyful, eager to discuss her love of Hawaiʻi and the women she admires. The 30-year-old has had her stories published in Granta, Conjunctions, and Joyland; Every Drop has been reviewed by Publishers Weekly, selected by independent booksellers as an Indies Introduce title, and featured by Book Riot as an excellent short story collection by an Asian author. We sat down with Kakimoto to talk story about her women, the kuleana of writing about Hawaiʻi, and the drop that is every man’s nightmare.

Kylie Yamauchi Let’s start with the story which lends its title to the entire collection. What led you to write about menstrual blood and Old Pali Road? How’d you even begin to bring them into conversation with each other?

Megan Kamalei Kakimoto Blood captures the beauty and horror of the female body, and it’s always been something that I knew in all my stories I’d be interested in exploring. I get excited when I see other fiction that unabashedly celebrates menstruation and talks about it in a very casual way because it’s a part of normal life.

As for Old Pali Road, so many superstitions that I grew up being warned about and am still reminded of by my family figures into historic sites. The Pali is so rich in moʻolelo, like the familiar story of not traveling with pork in the car. The Pali was part of the trek that I would make as a kid from here in Makiki to Gram and Papa’s place in Waikāne Valley. No matter how often we went, my mom always brought that story up. It really stuck in my head.

I was interested in taking a sacred site, figuring it as a central place where there’s so much heat already in terms of its history and moʻolelo, and zeroing in on one story of a girl: Tracing her from the moment of her first maʻi in this monumental place and chronicling her life as she contends with what it is to be a woman and to have a physical body, and to be concerned with things like bleeding and weight. It felt like a great intersection to start that story.

I really love exploring women’s bodies, the violence that’s visited upon them, and the immense power of them. I’m also interested in questions of isolation and questions of belonging. A lot of these passions extend outside of Native Hawaiian identity.

Megan Kamalei Kakimoto

KY Speaking of places, in the entire collection, there’s not a single image of Hawaiʻi as a paradise. The images that we’re so used to from tourist advertisements like white sand beaches, none are in your collection. In “Every Drop,” a lot of it takes place in private and grimy spaces. When it’s not in these spaces, it’s at Old Pali Road. What fascinated you about portraying this dingier and darker side of Hawaiʻi that people aren’t used to?

MKK I think a lot of that decision was subconscious. But maybe there was also my awareness of mainstream media’s depiction of Hawaiʻi. There’s, on the one hand, a real gut reaction of excitement that these [depictions] produce, from seeing your people and culture portrayed in art. But the consequence of our lack of representation in media is that when we are afforded entry and allowed to take up space, gratitude occludes the larger questions: Are these depictions respectful, are they authentic, are they thoughtful? A lot of times, contemporary portrayals of Hawaiʻi don’t let these questions enter into the conversation.

With this collection, one of the biggest things I struggled with was fear. I resisted writing about Hawaiʻi for so long. I had this big fear of failing to do right by this place and the pressure of that silenced me. When I decided to lean in and force myself to write into that fear, that’s when these stories came alive and I was able to meet the women who charge through this collection. It didn’t become a question of whether or not to write about Hawaiʻi because at that point Hawaiʻi was inextricable from the characters. And these women don’t live in glamorized portrayals of Hawaiʻi. It was a pleasure to explore a very different side of Hawaiʻi that I hope is still recognizable to Native Hawaiians and people who live here as well.

KY It sounds like you felt a heavy kuleana when writing this book. That’s not just something that Native Hawaiian writers face but all writers of color share, I imagine. You touch on this anxiety in the story of “Aiko, the Writer.” How there’s an expectation of writers of color to only write about their race and their own racial experience. As someone who works in publishing, I can say that’s how a lot of writers get pigeonholed. Do those concerns cross your mind ever?

MKK There’s this Carl Phillips quote I love so much that I have pinned on my desk. He talks about how he writes from a place where his gender, race, and sexual identity are never outside of his consciousness but they’re not the forefront of his consciousness either. It’s about allowing space to explore other interests as well.

I really love exploring women’s bodies, the violence that’s visited upon them, and the immense power of them. I’m also interested in questions of isolation and questions of belonging. A lot of these passions extend outside of Native Hawaiian identity. What I’ve come to terms with is being okay with following whatever obsession is in front of me and not letting questions of readership or audience or representation enter into, at least, the first draft phase.

KY In the short story “Aiko the Writer” there’s that great quote from her tūtū about the white gaze: “There are ways to tell Hawaiian stories and ways to make Hawaiian stories vulnerable to the white hand. And you’ll need to be extremely careful with your choices.” I assumed this is directly applicable to your writing process. When does the white gaze come into play?

MKK I think it only comes into play in revisions, for me. I also don’t know if it’s helpful at all to think about. I’m often overcome with anxiety: Will white readers read this and pull from this only the negative? Will they think I’m depicting a particular character as a villain? I have to remind myself that I know what readers I want to be reaching and what readers are going to resonate with these stories. I also understand there are certain things out of my control, in terms of how some stories are read and interpreted, especially by people outside of my lived experience. Having to come to terms with that has been a bit of a process, but it’s been important to keeping my sanity [laughs].

KY I think you did a really good job in this book of not explaining too much to white readers.

MKK That’s good to know.

KY That you don’t define every Hawaiian word, or that the Hawaiian words aren’t italicized and spelled with the correct ʻokina and kahakō, makes a difference. What also struck me was how all of the women in this collection were far from perfect. They’re not what I’d call “mana wāhine.” Sadie, for instance. If you read the collection in order, Sadie is the first Kanaka woman that we meet and she’s not what we expect her to be. She’s sickly, kind of a pushover, and silent. What went into the construction of this character and why not write someone who is more traditionally feminist, if that’s even the right word? I feel like she changes by the end of the story, so how do you read her at the end?

MKK I love a messy protagonist. Starting with her maʻi, the story tracks monumental moments in Sadie’s womanhood. These are also moments when anyone would be really vulnerable and probably making bad decisions. I appreciate fiction that affords women the space to make mistakes and be messy, while also being rebellious and strong. Sadie’s a really great example of a messy woman and a silent one, like you said. She has moments of silence that feel incredibly frustrating to me but also deeply human.

So much of the story for me was tracking Sadie’s relationship with her body, which then becomes her pregnant body, and then it becomes the body that has housed a baby and has lost a baby, simply by giving birth. I actually don’t know if she’s in a different place by the end of the story as she was in the beginning.

KY Just to be clear, what even happens in the end?

MKK [Laughs] It’s super ambiguous. I know it’s a weird, open-ended ending. I hope it feels like one of those endings where there’s a whole other life to be lived beyond where the story ends. I really don’t think there’s a wrong way to read it. One could wonder, is it even a baby?

KY All the mothers in the book have really troubled or ambivalent relationships with their children. A question that I’m sure will upset some readers: How do you think motherhood factors into “madness,” or to put it less controversially, into a shared struggle?

MKK I am not a mother, so my perspective is going to be incredibly different. But I am a daughter and so much of my upbringing has been wonderfully influenced by my mom. But I have a lot of fear and anxiety of ever becoming a mom, because it feels like the most pivotal responsibility. Something that has drawn me to writing about motherhood has been investigating the different ways to be a mother and ways to care for a life. A lot of times, in my own experience as a non-mother, as a woman, there’s so much expected from me all of the time. I think it’s often hard to even conceive of what my life would look like with a child.

KY Yeah, I think about this all the time.

MKK It keeps me up at night sometimes. Some of my biggest obsessions are my biggest anxieties. So having the space on the page to explore what it means to be a mother is almost therapeutic. It doesn’t take away the anxiety, but it gives me an outlet to consider what being a mother even looks like.

KY This collection was very much in the same vein as Her Body and Other Parties by Carmen Maria Machado and The Dark Dark by Samantha Hunt. I love how there’s been an outpouring of these short stories, tackling what it is to be a woman. But a lot of times, it’s usually written from the point of view of a white woman. “The Yellow Wallpaper” is most people’s first creepy short story about a woman losing her mind because of the pressures of marriage. I really like how your collection is very specific to Hawaiian women. What makes the “madness” of Hawaiian women distinct?

MKK When conceiving of this book, I was interested in locating the intersection of Indigenous women’s bodies and the wounds of colonization. How do native women respond to this violence and what is the horror that’s innate in possessing a body already rooted in a history of violence? Seeing these women in the collection react messily or horrifically was just as thrilling as when they chose camaraderie or compassion. Affording that range of responses was really important to me.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

MEGAN’S OWN OBSSESIONS

We asked the author for her recommendations.

Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma by Claire Dederer

The question of discomfort and of how to handle art made by monstrous individuals is one that’s constantly on my mind, and Dederer’s book-length negotiation with it speaks to all my interests.

Walking on Cowrie Shells by Nana Nkweti

What I consider a must-read collection. Truly impossible to finish it unchanged.

“Not” by Big Thief

Lately I’ve been listening to this song on repeat while writing fun flash pieces. I’m obsessed with the idea of an entire song made up of negations.

PopCorners, Kettle Corn flavor chips

Yes, I did order these delectable salty-and-sweet treats in bulk while working on revisions to the collection and novel-in-progress. If anyone deserves to make it into both books’ acknowledgements, it’s PopCorners.

Kakimoto’s debut collection was released in August 2023. The stories that result are unsettling and touching, and an ode to the complexities of Hawaiian femininity.