Freediver and designer Nico Jager crafts shell jewelry that conjures the ocean’s elemental energy.

Images by Shiloh Perkins. Hero image by John Hook.

Styled by Single Double

Assistant styling by Raigen Brabham

The jeweler Nico Jager’s design studio is little more than an office desk. Inside the garage of his childhood home in Kāne‘ohe, the space is wedged beside a 15-foot sailing boat and surrounded by stacks of Yeti coolers, its countertop littered with hundreds of shells. Some are categorized by type (spikes, cones, cowries) in teeming jars, while others are casually gathered in stray containers, like the ‘opihi shells he has stored in a lau hala basket. I wonder aloud how difficult it must have been to harvest one for the spiked ʻopihi necklaces his brand, 444ever, has become known for, let alone the dozens that he has accumulated over the course of three years. So notorious are ʻopihi for being dangerous to harvest, clinging to rocky shorelines pounded by churning waves, that one rather grim ‘ōlelo noʻeau — “He ia make ka opihi” — deems it the fish of death. (Another adage jauntily warns: “White water coming, no foolin’ around / ʻOpihi man in the sun / ʻOpihi man grab your bag and run.”)

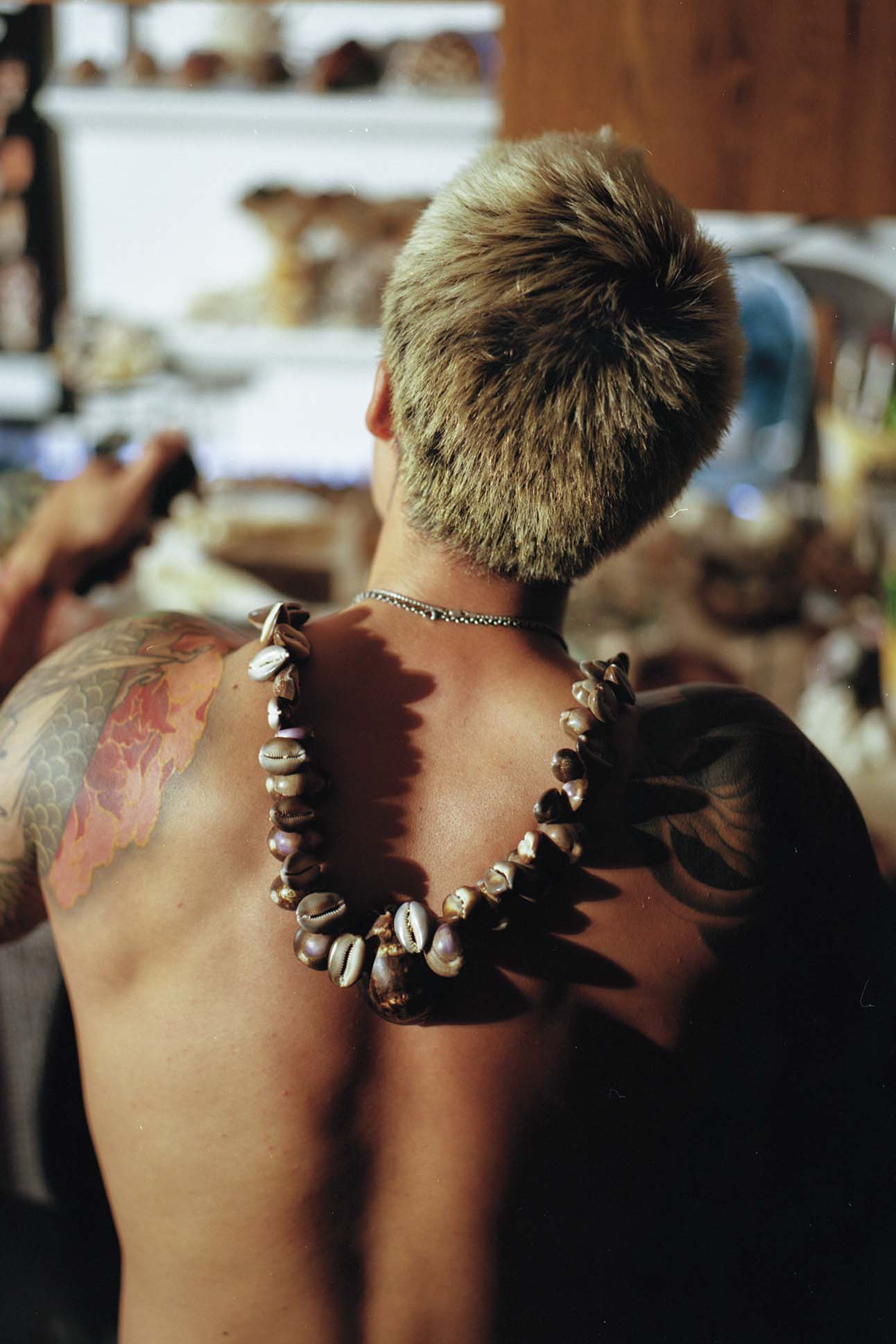

“Yeah, the danger, it’s very addictive,” says Jager, as he gives me a tour of his workshop on a brisk December morning, Jawaiian music leaking out from his phone speakers. Bleached blonde and tattooed, Jager telegraphs a certain punk attitude, describing the rush of picking shells while a large wave crashes overhead, praying that he can avoid the rocks below. “But at the end of it, the reward is these beautiful shells,” he says. “It’s like they’re so beautiful that it keeps me going back to these dangerous spots.” With this, the little conches that I thought were so dainty and charming began to take on the fact of their true form: hardy exoskeletons that dwelled in the ocean’s deep, relentless chaos.

Shells are among some of the first objects ancient humans used for self-adornment. The oldest piece of jewelry in the world is a beaded necklace of perforated shells found in Morocco, dated to be at least 142,000 years old. In Hawaiʻi, shells would be strung together into lei for personal decoration or exchanged as gifts. In an archipelago devoid of gems and metals, shells, along with bird feathers, nuts, and flowers, became the coveted materials of ornamentation. From the 1960s, when surfers began sporting them as chokers, Hawaiian shell jewelry saw periodic waves of trendiness beyond the islands. (Actor and singer David Cassidy’s iconic puka shell necklaces, as seen on episodes of The Partridge Family, is often credited with popularizing them in mainstream America.) Today, the precious shell lei of Niʻihau, made up of hundreds of miniscule shells handpicked from the island’s beaches, are considered among the most expensive shell jewelry in the world — the only shell lei that can be insured like diamonds. Many cost upwards of thousands of dollars, due as much to the labor and time it takes as to the shells’ extreme rarity, given that access to the island is limited for outsiders. Still, common association persists, deeming shells as dainty and feminine, a characterization seen in many popular, boho interpretations: a sunrise shell elegantly draped from a thin, gold chain; tiny, spiraling cone shells transformed into delicate earrings.

The waves are crashing on the rocks, and there are all these big creatures swimming next to you, vana everywhere, sharp, jagged rocks — there’s a whole side of danger and power that captivates you, and it pulls you in.

Nico Jager

To Jager, though, these shells are more than just pretty little things. “A little ocean mollusk, its whole life purpose is to create this shell as protection, as an adornment for itself. This is the outcome of the life of a mollusk, a shell. It leaves you in awe,” he says in an almost childlike wonder. Jager grew up accompanying his father to the beach, scrounging the shoreline for rocks and corals and, of course, shells, while his father kitesurfed in the distance. It’s a memory that he rhapsodizes about lovingly, recalling the joy he felt playing and foraging in the sand. Over the years, though, other interests pulled him away from the ocean, until a friend invited him to go diving for shells at Keawaʻula Beach. “It was during Covid-time. There wasn’t much we could do,” he says, referencing the social distancing regulations that rendered many public spaces, other than the ocean, inaccessible. “I wasn’t much into shells at the time. So, I was like ‘OK, I’ll go along, and just see how it goes.’” That first dive, he came back ashore with a handful of cowrie shells, nothing special considering the collection that he has now. And yet, the act, like the beachcombing treasure hunts he had as a child, unearthed a long-buried affinity for the ocean and its malacological wonders.

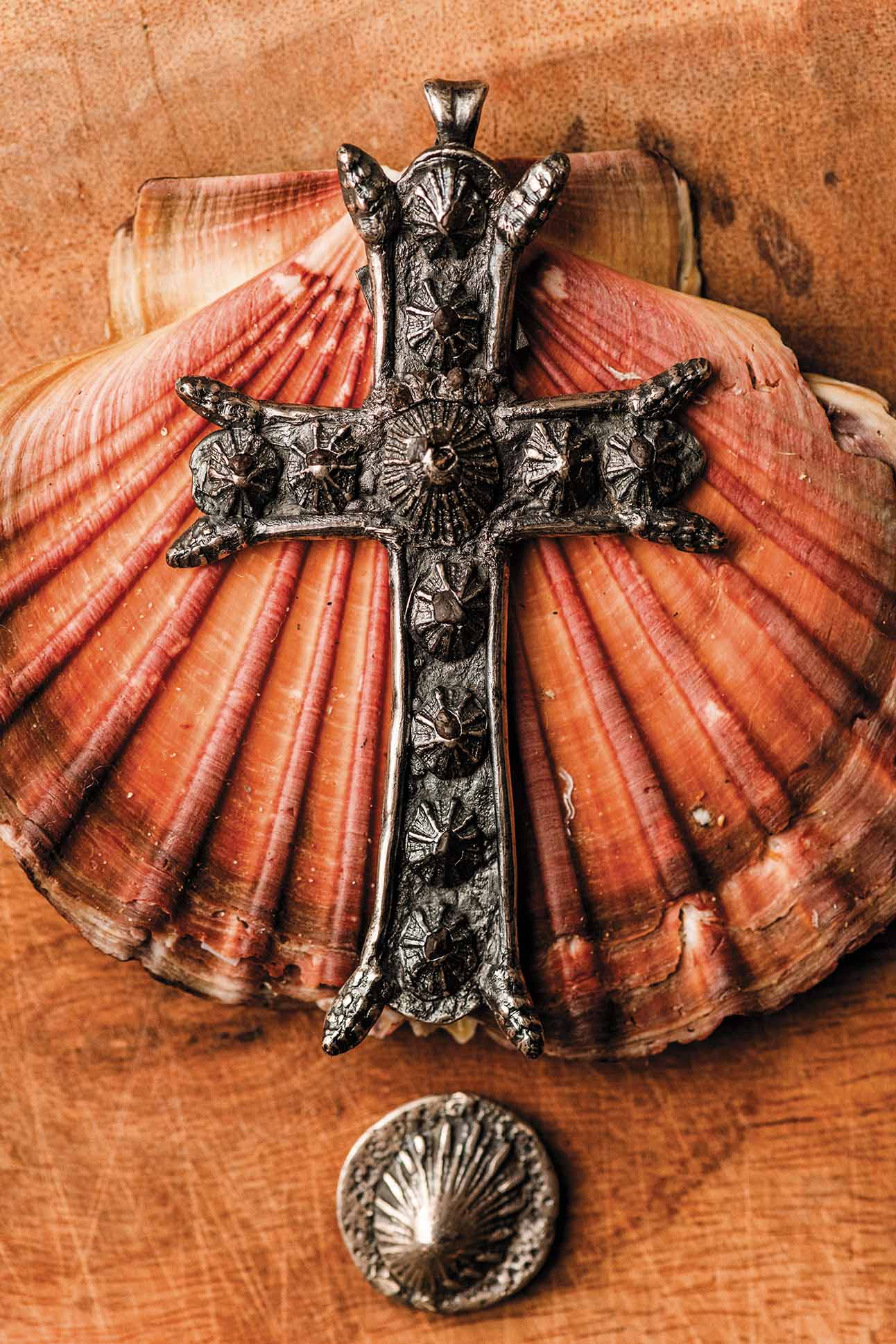

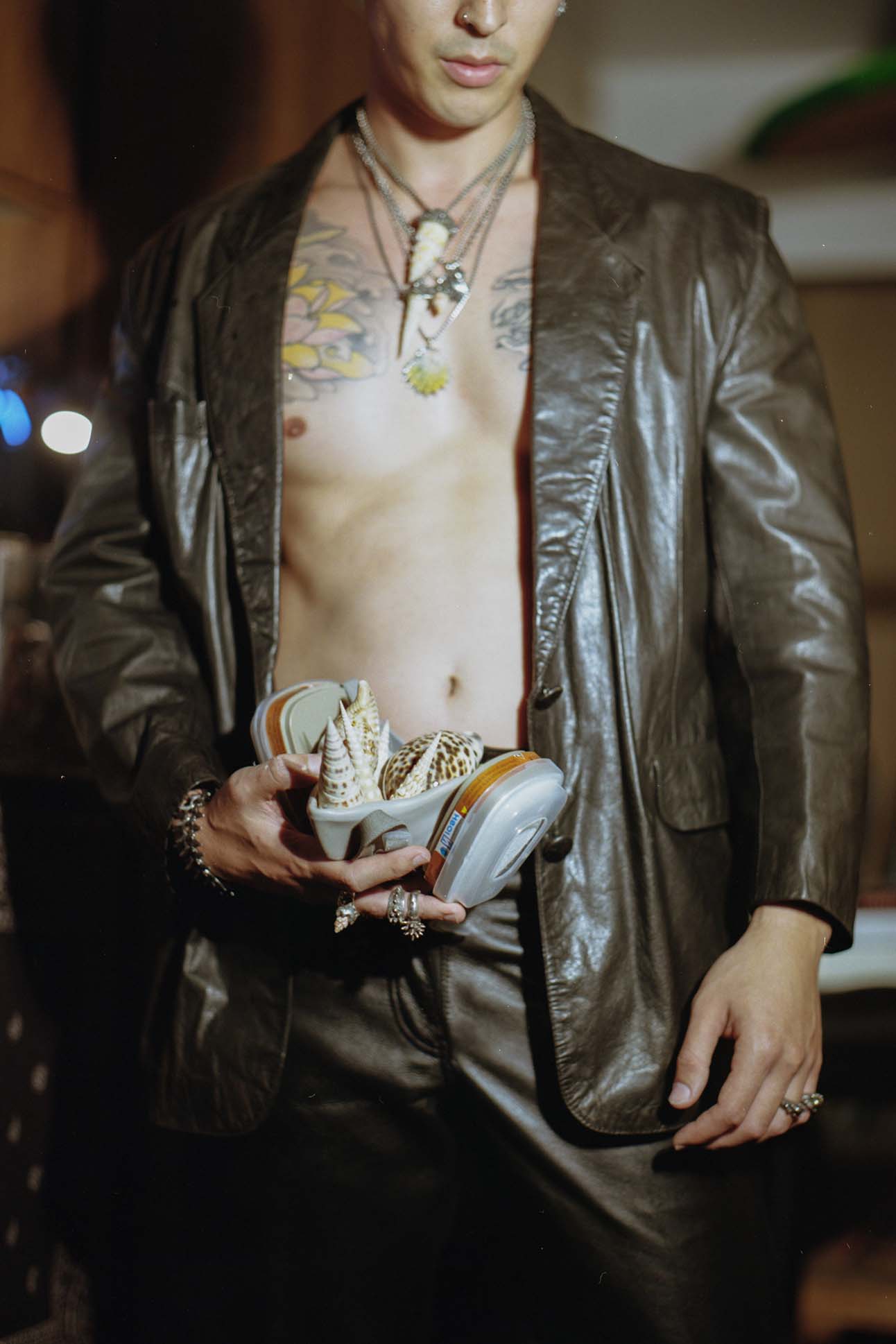

Inspired, he began to make jewelry out of the shells he dove for. He signed up for an introduction to jewelry making course at the Honolulu Museum of Art School, then taught himself the rest through online tutorials and plenty of nights improvising above the stove of his old Kaimukī apartment, smoke wafting everywhere as he solders materials together. He remembers his first iterations were merely experiments in how many spikes he could fit on a piece, hand-pulling each barb to give the shell a “raw edginess, that spice,” he says. It’s not surprising that Jager lists Chrome Hearts as one of his aesthetic inspirations, known for its gothic-inspired sterling silver jewelry. One can see the influence in Jager’s rings, thick metal biker-like bands textured with shells such as ʻōpihi and Hawaiian spindle, both of which he found on Oʻahu’s south shore, not to mention the pendants that hang from chunky silver chains styled like a large baroque cross dotted with ceramic ʻopihi or a five-pointed star casted out of shark teeth.

The sentiment behind each piece, though, is all Jager’s. He speaks about the ocean and her shells in rapt, sacral tones. “The ocean is my church,” he says. “When you’re diving, you can’t talk to anybody. You’re underwater, and you’re left alone with your thoughts. It’s so meditative for me. It’s like a spiritual thing.” In 2023, Jager began to freedive more regularly, a method of shelling that has brought a new philosophy to his process, like succumbing to a Dasein state. Without the aid of scuba tanks, each dive lasts for as long as Jager can hold his breath, making it all feel “like borrowed time.”

As a result, the chance of finding shells become all the more special. “You can put yourself in the right spot, in the right beach, you can go at the right conditions. But if the ocean doesn’t want to present its treasures to you, you’re not going to see nothing,” he says. “You’ll come out and just see rocks and sand.” Add to this the inherent dangers to diving in Hawaiʻi’s waters, from serrated rocks to pounding surf to prickly wildlife, and every shell Jager comes back with feels like a small miracle. His jewelry, then, is a wearable embodiment of that ephemeral thrill, a marriage of the ocean’s delicate beauty and crushing will. “It’s like a memory museum,” he says. “What all these shells are are just reflections of moments in time.”

The following Saturday morning, Jager is manning a booth at the Kakaʻako Farmers Market, his first public event since starting the brand in 2022. He’s chatting with a customer about his latest dive, when he came across a moray eel amongst the coral. His latest wares are artfully arranged across the countertop — studded rings and spiked necklaces and shark teeth earrings draped over black velvet boxes. Another customer, this one with a young daughter, approaches. Jager greets them both with a broad smile, carefully explaining the various shells displayed across the table, like a scientist expounding on his specimens. There’s a reverence in the way he speaks about the shells, in the way he treats them as if they were the world’s most precious jewels. Humans have held shells in high esteem for centuries, says Jager, who laments how technology has pulled us away from the earth’s natural beauty. “My end goal is to have a whole movement of our generation admiring the seashells and being in awe of that again. It’s a very raw form of art. It’s nature’s art,” he says. “I just want people to be as mesmerized as I am.”