Images courtesy of Honolulu Museum of Art

“When I was in art school, my professor would tell us that when times in history change, so does the art,” Aaron Padilla says, as he walks through the halls of Honolulu Museum of Art Spalding House, gesturing towards the pieces hanging along the walls. A pair of sculptures adorned with sea life and debris nod to marine pollution. Another work depicts a close-up of a clenched fist, defiantly raised in solidarity with historic resistance movements. “And right now, the times are changing,” Padilla says. “People are reacting. Artists are reacting.”

For the past five years, the museum has held annual educational exhibitions. Several, like 2016’s Plastic Fantasic?, focused on controversial issues, re-contextualizing works and curating narratives that bring different perspectives to points of contention. This year’s collection, titled The World Reflected, is no different.

In the wake of the 2016 presidential election, groups gathered to protest a stagnant government. Marches were made against social inequality. Donald J. Trump’s presidency became a magnifying glass, drawing the public’s attention to the country’s shortcomings. Times such as these, now and in the past, have served as catalysts for artists. In The World Reflected, works by renowned contemporary artists are brought back into the spotlight. But this time, amid today’s issues and conversations, their meanings are amplified.

In one room hangs a series of eight mono-prints, titled Dead Indian Stories, by Edgar Heap of Birds. On the blood-red canvases are phrases, painted as if with an urgent hand. “Happy to donate what you took,” reads one. Another, “Built three forts Indian never safe.” Across from these is the grand lithograph of an American flag by late artist Vito Acconci. Alone, the works deliver different messages. One unapologetically lambastes the suffering a group of people has had to endure. Another questions patriotism. But together, they forge a narrative that reexamines what it means to be an American.

Instances such as this can be found throughout the exhibition. The collection’s pairings create spaces for questions and conversations about today’s social climate. “An artist can react in response to something,” Padilla says. “But on the flipside, art has the power to actually elicit some kind of shift in somebody’s idea or culture.”

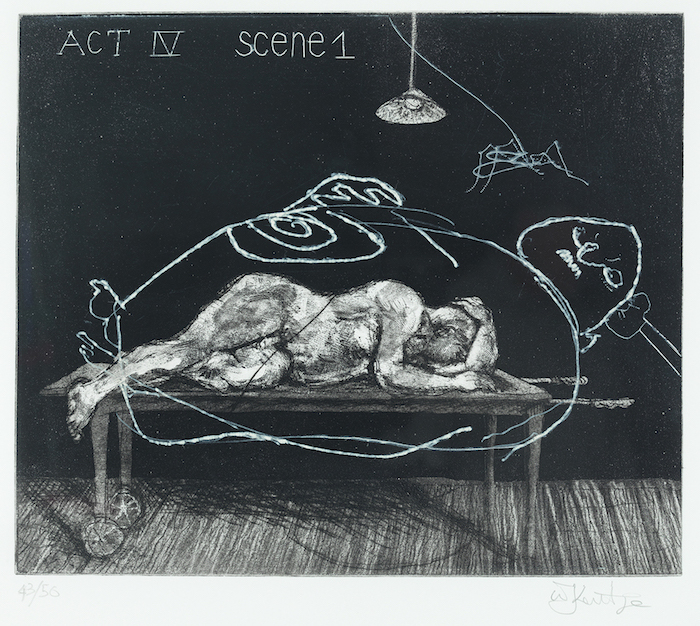

For many, art manifests the voices of the people. William Kentridge’s prints depict life during South Africa’s apartheid; Kara Walker’s works, specifically Means to an End, evoke how it feels to be an African-American woman in the United States. Viewing history through the eyes of these artists provides access to multiple perspectives. And unlike textbooks, says Padilla, they do not merely tell the audience, but show us what occurred. They let us make our own conclusions.

By contextualizing these works, Padilla and his team hope that viewers will rethink their issues. “How do you relate the work back to your own life?” Padilla says. “Sometimes it’s affirming, and sometimes it’s critical. And if you can expand your perspectives through a work of art, then that is a success.”

The World Reflected will be on view at The Honolulu Museum of Art Spalding House from July 27, 2017 to October 28, 2018.