For the past three years, filmmakers Joan Lander and Sancia Miala Shiba Nash have been digitizing and cataloging the Nā Maka o ka ʻĀina film archives.

Images by Vincent Bercasio

The installation for Ahupua‘a, Fishponds and Lo‘i, despite a spartan title that conjures impressions of agricultural abundance, was sparsely furnished. No framed works or large sculptures decorated Koa Gallery, the arts space at Kapiʻolani Community College. In a corner, a pair of small video monitors played outtakes from the 1992 documentary which shared the exhibit’s name. Inside a dimly lit alcove, the film’s full 90-minute runtime was projected on a loop. Placed modestly at the room’s center were two desks; one held an iMac, the other a pair of binders labeled “Hoʻomana Logs/Transcripts Oʻahu.” To the unacquainted they would have seemed like footnotes to the exhibit. For those familiar with the work of documentarians Joan Lander and Abraham “Puhipau” Ahmad Jr., however, their contents were a revelation of utility.

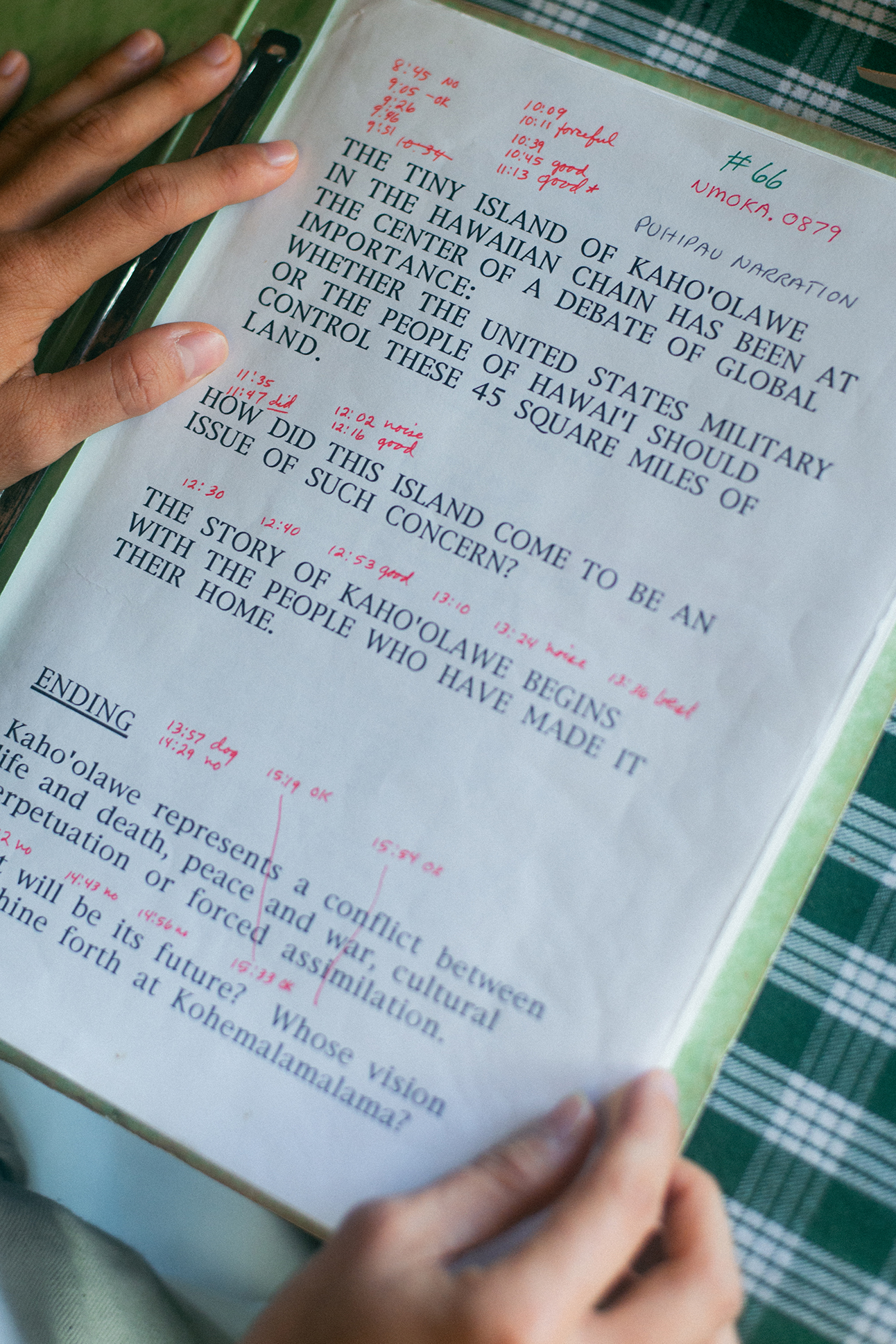

The binders housed a stack of transcripts two inches thick, meticulously cataloged by Lander and Puhipau as they filmed the Oʻahu segment of Ahupuaʻa, Fishponds and Lo‘i (1992), their seminal Nā Maka o ka ʻĀina documentary on Hawaiian aqua and agricultural practices across the islands. The installation made the film’s unabridged transcripts and outtakes public for the first time in 30 years, showcasing more than 80 unedited hours of oral histories on traditional Kānaka knowledge, storied places, and Hawaiian history.

One scene followed Marion Kelly, an activist and ethnohistorian credited with reorienting academia’s view on Native Hawaiian history, as she and educator Charles Kupa toured Ka Papa Loʻi o Kānewai, Mānoa Valley’s last intact taro patch. In another interview, omitted from the film’s final cut, kumu hula Frank Kawaikapuokalani Hewett traced his ancestral origins to Puʻu Hawaiʻi Loa, a wahi pana, or storied place, made inaccessible by the creation of Kāneʻohe Marine Corps Base. “Where did we get this beautiful word, this magical word, this word that imparts life called aloha?” Hewett asks, standing in ankle-deep water with his homelands in the background. “Believe me when I say, and I truly believe this, that the Hawaiian people or Hawai‘i are truly blessed because of that.”

Film stills from Mauna Kea Temple under Seige (2005), Kaho’olawe Aloha ‘Āina (1992), and Pacific Sound Waves (1986).

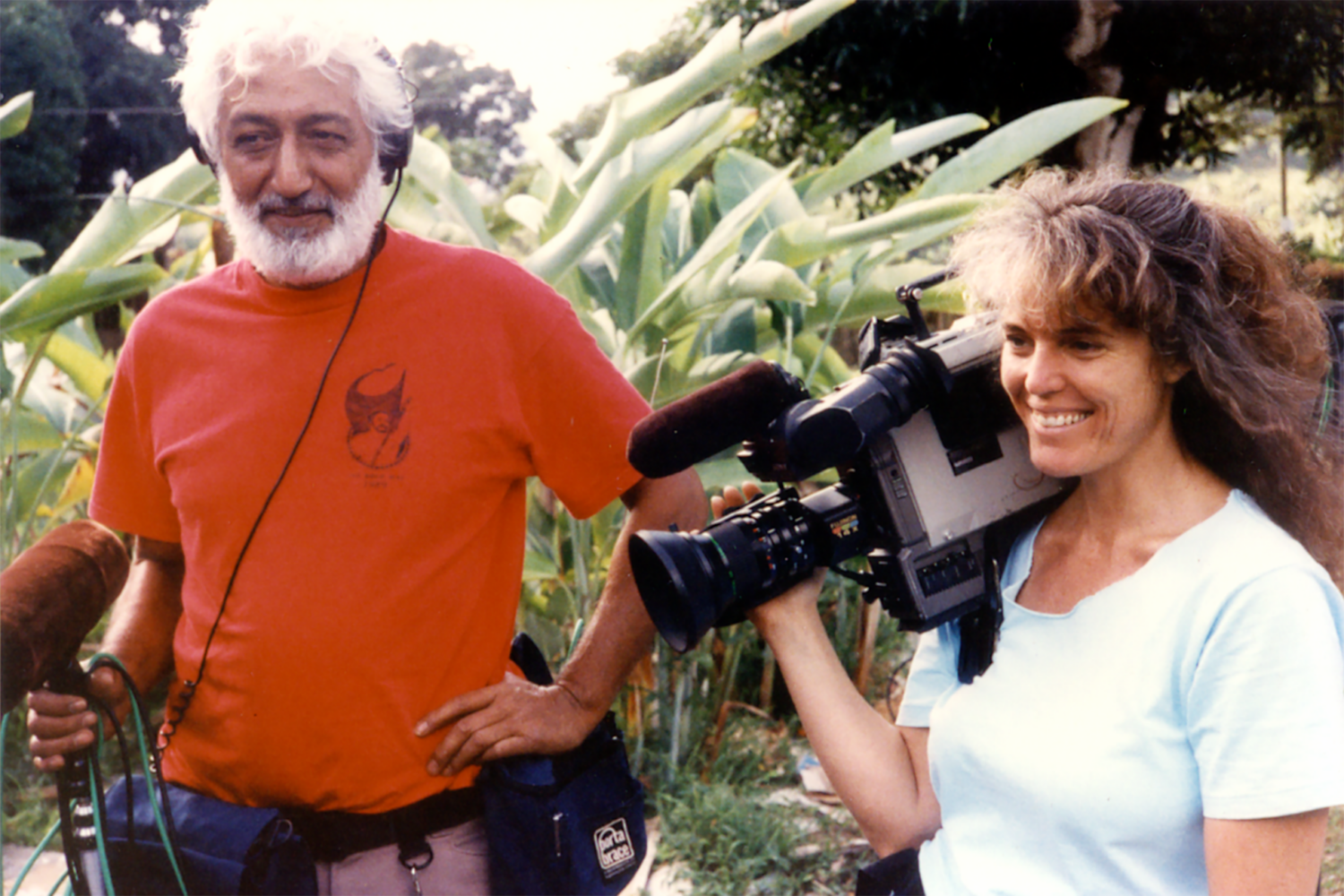

The installation was the culmination of a three-year collaboration between Lander and filmmaker Sancia Miala Shiba Nash, enlisted by the Native Hawaiian non-profit Puʻuhonua Society to help catalog and digitize Nā Maka o ka ʻĀina’s vast moving picture archive. Lander and Puhipau founded the independent video production company in 1981 after meeting in the post-production process for Victoria Keith and Jerry Rochford’s The Sand Island Story, which documented the state’s forceful eviction of a largely Native Hawaiian community on Mauiola (Sand Island). Lander was the editor; Puhipau, as one of the residents facing eviction, was asked to narrate. The pair’s serendipitous beginning was a portent of the work they would accomplish in the ensuing years.

It was the 1980s, the decade after the Second Hawaiian Renaissance, which had heralded a political and cultural rebirth. There was a renewed focus on Native Hawaiian history and art. Political resistance called for a return to sovereignty. Lander and Puhipau turned their lens to the social movements occurring around them: evictions, land and water rights protests, and aloha ʻāina marches. It was all, according to the Hawaiian-Palestinian Puhipau, “for one purpose only, and that purpose is to speed up the process towards sovereignty.”

For more than 40 years, the duo covered traditional and contemporary Hawaiian culture, history, and politics, producing the resulting footage into award-winning programs. By 2006, Nā Maka o ka ʻĀina had amassed over 8,000 videotapes, stored in Lander’s Kāʻū home. The recorded materials were fragile, the technology used to play them facing obsolescence. To avoid losing the archive, Lander and Puhipau began cataloging, digitizing, and archiving. They transferred most of their edited programs online. Then, in 2016, Puhipau passed away, making Lander the archive’s sole proprietor.

The stories that we record are important because they can offer solutions for the future of Hawai‘i.

Sancia Miala Shiba Nash, filmmaker

The next four years Lander continued alone. Yet, digitizing thousands of hours of footage proved to be a monumental project to undertake solo. In 2020 she began working with Puʻuhonua Society, a Native Hawaiian nonprofit who provided funding for additional equipment and manpower. Nash was enlisted to digitize the transcripts, applying precise metadata like names and locations, and to organize public programming opportunities.

Nash, who studied film and anthropology at Bard College in New York, moved back to Hawaiʻi in 2020. A family friend, kahu and musician Wilmont Kamaunu Kahaialiʻi took her to storied sites across Maui upon her return, recalling the moʻolelo tied to the land. Among them was Honokahua, an ancient burial site reinterred in 1987 to make way for a Ritz-Carlton resort. Shortly after, she watched Nā Maka o ka ʻĀina’s Na Wai E Ho‘ōla I Nā Iwi—Who Will Save the Bones? (1998) about the desecration. The pivotal moment soon led to her collaboration with Lander. Their partnership was named Ho‘omau Nā Maka o ka ʻĀina, ho‘omau meaning to continue.

They first tackled the more than 86 hours of footage filmed in 1989 to 1990 that became Ahupuaʻa, Fishponds and Loʻi, produced by Nālani Minton. “We had to go through the dozens of stories left on the cutting room floor, identifying the subjects and distributing the footage to families,” says Lander. “Puhipau and I believed that the people on the tape had as much right to the footage as we do. The most satisfying thing has been to put a copy of the tapes in the hands of the people who were on it or relatives of those who have passed.” With the permission of the families, certain tapes were made available to the public via installations like the one at Koa Gallery, which featured interviews done on Oʻahu.

“It’s one of these programs that you are both absolutely honored to be part of and completely overwhelmed by the sheer amount of work that it requires,” says Emma Broderick, executive director at Pu‘uhonua Society, which also provided funding for the public programming.

As I grow older, I feel such a responsibility and urgency to get the tapes out there and accessible.

Joan Lander, co-founder of Nā Maka o ka ʻĀina

The most interactive aspect of the exhibit was the iMac set up in the middle of the room, which housed the transcripts digitized by Nash along with an archive of previously unseen Oʻahu tapes. The metadata in Nash’s transcripts made the hours of footage easily searchable. One could type in “taro” and find where among the tapes it was discussed. Instantly, there Kelly would be, explaining how the sugar industry diverted water away from the taro patches. Or kalo farmer Charles Reppun showcasing the traditional irrigation methods of his Waiāhole farm. The tapes provided invaluable knowledge, made available to journalists, researchers, students, teachers, and cultural practitioners.

In a way, the program isn’t merely to create a historical archive for researchers or future documentarians. It presents a tangible link to Native Hawaiians’ past, proof of the ways in which Kānaka Maoli have fought and continue to fight for the rights of their people and land.

“I feel like many grassroots documentary filmmakers of Hawaiʻi would agree that Nā Maka o ka ʻĀina left a vital resource for generations to come,” says Nash. “We still look to their educational programs and video archives for insight, as many of the issues they recorded still persist today.” In documenting the stories of ka pae ʻāina, the Hawaiian archipelago, Nash believes that Lander and Puhipau’s legacy played a critical role in educating the people of Hawai‘i.

Eventually, the Ahupua‘a, Fishponds and Lo‘i installation will travel to the various islands in which the documentary was filmed. The next island will be Maui, where the Maui portion of the tapes will be on display. Although the Oʻahu exhibit closed in 2024, the digitized footage and transcripts remain housed at Arts & Letters in Chinatown and, accessible by appointment, the Kualoa-Heʻeia Ecumenical Youth Project in Kāneʻohe.

“I appreciate the ho‘omau, the continuity piece that spans across generations with Nash and Joan. Not only are they able to continue the work as it exists and honor it as a source, they can evolve the work,” says Broderick. “It is beautiful to have a filmmaker working with a filmmaker, and not necessarily a filmmaker working with an archivist, as Nash brings her perspective to the project, as we can see with the exhibits.”

The project has made a mark on Nash and her experimental filmmaking, which is influenced by oral histories. The Hawaiian proverb “i ka wā ma mua, ka wā ma hope,” meaning the future is in the past, is particularly inspiring for her work. “The stories that we record are important because they can offer solutions for the future of Hawai‘i,” she says.

There’s much more work still to be done. Lander and Nash continue their collaboration with the next set of 256 tapes from Nā Ki‘i Hana No‘eau Hawai‘i, a 30-part series on Native Hawaiian culture created for the Department of Education. Once all the tapes from Nā Maka o ka ʻĀina’s archives are digitized and cataloged, the raw materials and transcripts will be deposited at ʻUluʻulu: The Henry Kuʻualoha Giugni Moving Image Archive of Hawaiʻi, the official state archive for moving images, to ensure their future preservation.

“As I grow older, I feel such a responsibility and urgency to get the tapes out there and accessible,” Lander says, “and I’m so grateful to have the partnership of Pu‘uhonua. They’re treating my and Puhipau’s work with such respect and have seen its value.”

Correction: A print version that ran in Issue No. 46 misstates the name of a subject’s family friend. His name is Wilmont Kamaunu Kahaialiʻi, not Aaron Kamauna. The online version also includes an attribution for the film, Ahupuaʻa, Fishponds and Loʻi, to producer Nālani Minton.