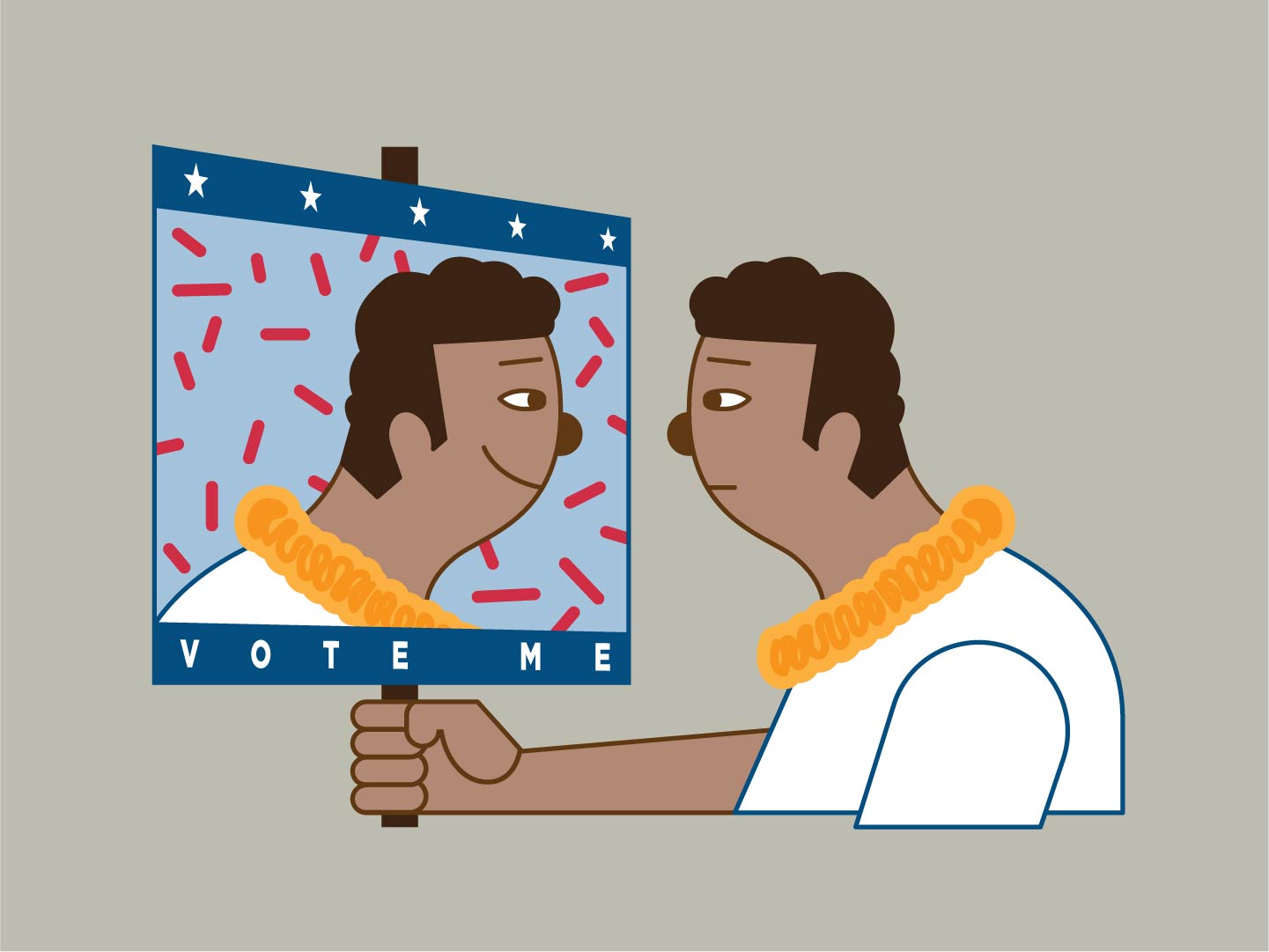

A Millennial journalist-turned-hopeful politician tracks the rise and fall (and rise again) of his political ambitions.

Illustration by Mitchell Fong

I didn’t dream of being in politics as a kid. My childhood experiences with prefects and bullies fostered a lasting distaste for power. If I identified most with anyone at that age it was the anthropomorphic fox from Disney’s Robin Hood. Like him, and most people who are powerless, I view the elite with a healthy dose of skepticism.

Early on I figured that if I would never have political power, at least I could understand it, and maybe outsmart it. Later came college degrees in policy and political science, a law degree that emphasized critical race theory. I wrote everything possible about broke artists and struggling athletes. I paid the bills representing domestic violence victims and those in the vice grip of the criminal justice system.

Then I found myself in Kalihi, home to a working-class community of Filipinos, Pacific Islanders, and the islands’ growing Micronesian and Chinese immigrant community. They reminded me of my own mixed-up immigrant family. I attended funerals and first baby lū‘au. I walked with kids along streets with potholes that seemed like portals to alternate dimensions, by gambling houses as famous as the Bellagio, through a 10-block neighborhood that floods most days.

Even the progressive advocates told me the neighborhood used to be a swamp; as if it’s just the natural order of things, the way regular working people get swept away when the waters rise. As if Kalihi wasn’t a mile away from the most advanced military base in the history of the world. As if places like Washington D.C., Manhattan, London, or Waikīkī weren’t swamps too. Nothing seemed fair when I met kids who got lead poisoning, kids with the worst dental health in America, local kids without shoes.

So, what if I broke character and sought power? What if I ran? Over the years, the politicians I met were, for the most part, well-meaning people with shortcomings similar to my own. Many of them are straight-up lazy. I hit the streets with my dad and tita who spoke Tagalog and Illocano, friends, lovers, and anybody willing to wave a sign. The new mode of life went against the habits I had acquired over the previous three decades.

I felt like an outsider at every turn. I spent six months in the elements, punctuated by constant meetings and awkwardly plastering my face all over the neighborhood. The equivalent of a down-payment for an apartment was spent on mailers, websites, and community events. They described a goofily simple platform of fairness, dignity, and labor. I worked so diligently to avoid being exposed as a political fraud that I ended up becoming a legitimate politician.

We lost, barely, but that’s a subject for another essay. The next campaign begins in a few months. In Tagalog we’d say “pag pag,” kicking the dust off your feet to keep moving.

I’m hoping the next campaign goes like the last scene in Robin Hood, when the fox exclaims, “Fear not, my friends. This will be my greatest performance!” as he dodges an arrow to the butt and another gets stuck in his hat, shoots the camera a wink, just before scaling the castle wall.