Images by John Hook

In the late 1960s, a great gray wave crashed onto the shores of Hawai‘i. It had originated from Europe nearly 20 years earlier. It traveled west to the Americas and east to Asia, and as it rolled from continent to continent, city to city, the swell grew. By the time it reached Honolulu, arriving from both the United States and Japan, the architectural movement known as Brutalism had become one of the dominant styles for civic buildings around the world, from hospitals to public housing, university buildings to city halls.

Born out of post-World War II austerity, Brutalism was defined by bold, sculptural, monumental concrete forms assembled in ways that seemed to defy gravity. Hawai‘i’s first and arguably best Brutalist building is the Financial Plaza of the Pacific, which takes up an entire city block bounded by King Street, Bishop Street, Merchant Street, and what became Fort Street Mall. The building is actually three: a 21-story tower flanked by two office buildings, one 6 stories, the other 12, all rising from a large public plaza. The tower, top-heavy with a hypnotic grid of recessed windows, was a stark departure from the inventive yet largely delicate architecture of the midcentury, which by then had taken hold in the Hawaiian Islands.

The Financial Plaza of the Pacific was a landmark project for Honolulu, one that its boosters hoped would solidify the city’s status as a hub for both commerce and culture. World War II had hurt the islands’ economy. In 1958, to help revitalize Oʻahu’s central business district, a group of business owners formed the Downtown Improvement Association, which had three objectives: Attract more tourists downtown, keep the state and county seat near ‘Iolani Palace, and give the business district a defining anchor, something akin to New York City’s Rockefeller Center. The Financial Plaza of the Pacific became this anchor. The consortium hired some of the period’s best-known architects to design it, including Victor Gruen, who helped invent the indoor shopping mall, and Lawrence Halprin, the now legendary landscape architect who had just designed San Francisco’s Ghirardelli Square. The lead architect, Leo S. Wou, had emigrated from China to study in the United States and worked for Louis Kahn (a soon-to-be master of the Brutalist style) before opening his own office in San Francisco.

The buildings housed three distinct and powerful entities: Bank of Hawaii, American Savings and Loan Association, and Castle and Cooke, all of whom had been convinced by Robert Midkiff, the vice president of the Downtown Improvement Association, to pool their land holdings and create a joint headquarters that would redefine downtown Honolulu.

DeSoto Brown, the historian at the Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum, remembers watching the towers go up as a teenager. He’d gotten his first glimpse of Brutalism a year earlier in Montreal at the 1967 World’s Fair. (At the time, Brutalism was on everyone’s minds, if not their lips; the term was used by a select few.) Brown’s family stayed at Place Bonaventure, a soaring concrete hotel and exhibition center in downtown Montreal. He was mesmerized by its bold, unadorned concrete walls, which were juxtaposed against eye-popping, red-orange carpet. The combination was so unusual that he walked up to the wall and touched it. A year later, when the Financial Plaza of the Pacific opened in Honolulu, Brown’s father, a stock broker, moved his offices there, giving Brown VIP access to what was, at the time, the city’s most exciting architectural addition.

The concrete towers multiplied. The American Savings Bank Tower went up catty-corner to the Financial Plaza in 1972 sporting jagged vertical and horizontal ribs so sharp they threatened to cut careless passersby. The nearby Municipal Building (now named the Frank F. Fasi Municipal Building) was as smooth as the American Savings Bank Tower was rough. Resorts, airports, shopping centers, and university buildings all were designed in the Brutalist language. It showed up even in the unlikeliest places, like working-class Kalihi, where Japanese architect Sachio Otani designed a fortress-like dojo for a little-known religious sect called Tensho Kotai Jingu-kyo. However, downtown Honolulu remained the epicenter. By 1980, you could walk a half mile in any direction from the Hawai‘i State Capitol and never be out of sight of at least one of these monolithic brutes. Hawai‘i had entered a new era.

From the beginning, however, Brutalism had its detractors. Ian Fleming so hated the style that he named the James Bond villain Goldfinger for the Brutalist architect Ernö Goldfinger. In Hollywood, the style became the go-to architecture of pop culture villainy. From Blade Runner to RoboCop, Brutalism became, in one critic’s words, the “backdrop of evil.”

The irony is that Brutalism was born out of utopian idealism. The style’s progenitors—Peter and Alison Smithson, Le Corbusier, Moshe Safdie—shared a commitment to social welfare through architecture. Many early Brutalist buildings were grand experiments in social housing, such as Safdie’s Habitat 67—which debuted at the World’s Fair in Montreal—and Le Corbusier’s Unité d’habitation in Marseilles, France, for which the architect specified “beton brut,” or raw concrete. In the United States, which had escaped the lion’s share of wartime devastation visited upon Europe, monolithic concrete architecture represented authenticity, honesty, strength. As Amanda Kolson Hurley recently wrote in the Washington Post Magazine, architects of Brutalism were revolting against “the previous generation and its cool, glassy modernism, which by that point had become the architectural language of the corporate world.”

“Being monolithic meant eliminating applied surfaces, hung ceilings, sheetrock—eliminating everything except the concrete,” the architect Henry Cobb explained in an interview published in the 2015 book Heroic: Concrete Architecture and the New Boston. “We were enchanted by the idea that once the concrete was poured, the building was essentially finished.” This fascination with concrete was partially practical. In the years after World War II, steel was prohibitively expensive, especially in Europe. As a result, European architects had begun designing large-scale concrete buildings. Since many of America’s best-known architects of the time emigrated from Europe, they brought this ethos with them.

The same characteristics that drew mainland designers to concrete—its economics, its authenticity, its expressiveness—swayed architects working in Hawaiʻi. Unlike steel, which had to be imported, concrete could be made in the islands. The first known use of concrete in Hawaiʻi was in 1864 for the construction of a sugar mill on Maui. One hundred years later, it had become the material of choice for everything from hospitals to resort hotels.

Despite the style’s moniker, Honolulu’s Brutalist buildings were never meant to be dehumanizing. On the contrary, they were seen as benevolent additions to the urban fabric. The Financial Plaza of the Pacific was the first private development downtown to include such a large public plaza, complete with artwork. “Up until then, every building in downtown Honolulu built right out to the sidewalk,” Brown explains. The city’s metamorphosis was well received both in Hawaiʻi and abroad, and travel magazines fawned over the city’s “sophisticated new towers, malls, plazas, parks, sculptures, stores, and restaurants.” This is the Honolulu that Brown remembers, an increasingly cosmopolitan city that couldn’t get away from the past quickly enough. “You’re in the space age, you want to be different, you want to be modern,” he says of the late 1960s. There was an attitude of tabula rasa. “It was up, up, and away.”

No architectural style thrown into the utterly unique milieu of Hawaiʻi emerges unchanged. Soon Brutalism was metabolized into a more acceptable and appealing island aesthetic. Still wooed by concrete, architects found ways to soften their buildings to better fit Hawai‘i’s climate and culture. They ringed their buildings with coconut palms and hala trees, incorporated lava rock, and added concrete murals.

As ornament and indigenous material found their way into Hawai‘i’s concrete buildings, the architecture became something else. A resort like the Mauna Kea Beach Hotel on Hawai‘i Island—at the time the most expensive hotel in the world—was already anathema to the socialist ideals of the Brutalism’s earliest champions. But in blending wood, steel, and tile with massive concrete forms, such buildings also said goodbye to the stylistic purity being pursued by people like Paul Rudolph. A sort of hybrid architecture emerged, something both tropical and Brutalist and distinctly Hawaiian.

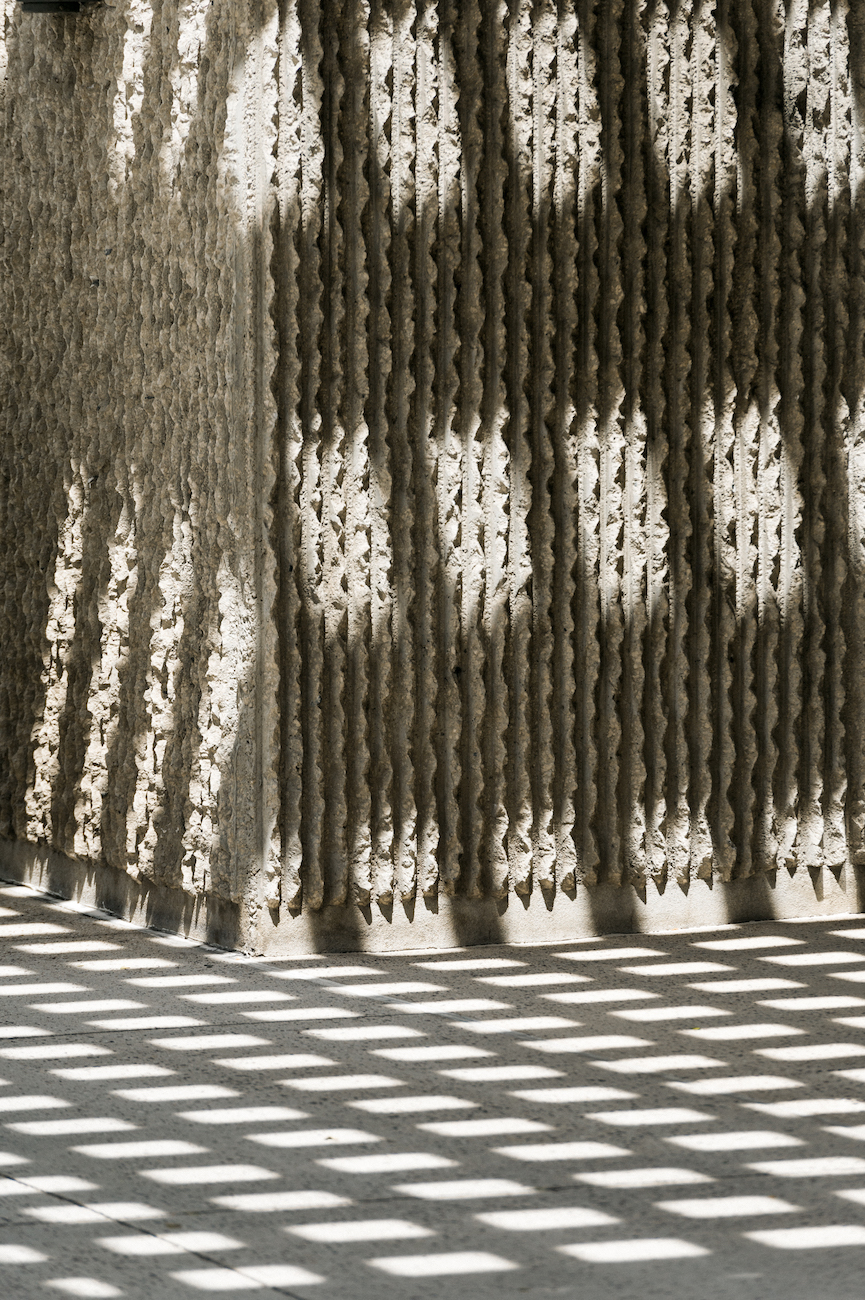

Despite the use of terms like “monolithic” (often used to mean not just large but devoid of character), there is an almost obsessive attention to detail in Brutalist buildings. On some, the exposed concrete is intentionally chipped or broken; on others, it swirls with the patterns of its wooden forms. Architects like Joseph Farrell, an acolyte of Rudolph’s and arguably one of the masters of Hawai‘i’s tropical Brutalism, chose different sizes and colors of crushed local rock to echo the area’s historic stone structures and evoke Hawai‘i’s beaches. What looks gray and lifeless from a distance becomes white and red and blue up close, an elemental architecture with a geologic patina.

Eventually, economics steered architects away from this labor-intensive way of building. The political climate shifted, too. In the 1980s, the welfare programs Brutalist architecture represented—and often housed—were gutted, as were the budgets to maintain these so-called monstrosities, a phenomenon known as “active neglect.”

However undeserved, the Achilles heel of these hulking brutes remains their misanthropic reputation, which threatens to allow them to be erased from public memory, just like generations of buildings before them. Chris Grimley, one of the authors of Heroic, recently mounted an exhibition titled Concrete Demolition at Boston’s Pinkcomma Gallery to highlight the destruction of this once-utopian architecture. In Hawaiʻi, Ward Plaza, a low-rise Brutalist office building at Ala Moana Boulevard and Ward Avenue, is actively being dismantled.

With loss often comes renewed appreciation, however, and there’s evidence that Brutalism is trending upward. A group known as #SOSBrutalism has built an online database of thousands of Brutalist buildings around the world in order to advocate for their preservation, and local preservation groups are beginning to rally around Hawaiʻi’s unique tropical Brutalism. Elsewhere, Brutalist history is being preserved in amber: London’s Victoria and Albert Museum acquired a three-story slice of the public-housing complex Robin Hood Gardens—the rest was demolished—and exhibited a portion of it at this year’s Venice Architecture Biennale.

Some architects think concrete buildings still have much to offer the islands. In his office at University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, Martin Despang, a professor of architecture, has a model of a speculative project dubbed Primitiva, envisioned as 30 stories of exposed concrete softened by wood finishes and left open to the air, with each residential unit screened by bamboo. Unlike the hermetically sealed steel-and-glass towers rising in Kakaʻako, Primitiva would take advantage of the island’s cooling tradewinds through what’s known as the stack effect, in which a central courtyard pulls cool air through the building as warm air rises. As for the concrete, Despang sees it as an indigenous material able to be made here on the islands.

Will the public ever see the beauty in this concrete architecture? It’s hard to say. Derivative architecture and the ubiquity of concrete has spoiled the novelty that Brutalism once enjoyed. Architects also may have been idealistic thinking that people would ever see concrete as humane. If a lava rock wall feels somehow warm, a concrete wall feels cold, impersonal—at least to many people. Perhaps concrete feels too rigid, too regular, for a species that seems to respond best to biomorphic forms found in nature.

Not every building is a work of art, no more than every paint-splattered canvas is a masterpiece. But whether or not it is beloved today, Hawai‘i’s strain of Brutalism helped define the islands. In its most shape-shifted form, it is a style of architecture found nowhere else. If these concrete buildings were idealist to a fault, that seems less the flaw of a villain, and more that of a hero.