Sally Lundburg and Keith Tallett’s artwork present urgent meditations on Hawai‘i families’ trying times.

It’s a warm summer morning and artist Sally Lundburg is not getting dressed for work. Rather, she’s getting undressed for it. While walking past stands of koa and ‘ōhia on the four-acre Pa‘auilo homestead she and her husband, Keith Tallett, call home, Lundburg strips down from her jeans and T-shirt and into a black swimsuit.

Nearby is a small pond, its still surface reflecting the deep greens of the surrounding forest. Lundburg slips into the water soundlessly and lines of inky water unfurl around her in languid, concentric circles. A few meters away, a floating piece of cordwood from a 2012 Honolulu Academy of Arts installation Lundburg created of koa logs, inkjet prints, silk, and epoxy resin reveals a sepia image of a man from Hawai‘i’s bygone plantation era. His gaze is stoic amid the rise and fall of the incoming eddies. Camera in hand, Lundburg examines the log with interest. It rests partially submerged at a curious slant, its exposed surface now textured with thin, white, raised wrinkles. It has no doubt been affected by its time in the pond.

The piece is one of 37 logs used in Sink or Swim, Lundburg’s mixed-media installation commissioned as part of a collaboration between the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center and Aloha United Way. In this work, Lundburg examines concepts of fragility and resilience—all-too familiar themes in Hawai‘i, where the struggle for financial security resembles a path along the razor’s edge. Living expenses in Hawai‘i are on average nearly two-thirds higher than the rest of the United States, and almost half of all residents live paycheck to paycheck, according to the Aloha United Way “ALICE Report: Hawaiʻi 2018.” According to this report’s findings, financial hardship is especially felt by a segment of the population termed as ALICE, an acronym for Asset Limited, Income Constrained, Employed. These are households with working adults who struggle to cover basic necessities such as food, housing, transportation, healthcare, and childcare and yet remain ineligible for government relief programs. In other words, households that are poor, but not poor enough.

Lundburg and Tallett, who is also an artist, were both commissioned to create a piece in response to the Aloha United Way’s findings. The two were given carte blanche to transform the report’s sheer volume of research and complex analytics into something alive: art. “It’s this giant, almost overwhelming document full of data, graphs, and numbers,” Lundburg says. The report struck a personal chord with the couple, too. In reading about struggling families, they recognized their own. “I remember thinking, ‘Whoa,’” Lundburg says. “We fit into that category.”

In reading about struggling families, they recognized their own. “I remember thinking, ‘Whoa,’” Lundburg says. “We fit into that category.”

Upon reading the report, Lundburg recalls being drawn to the idea of buoyancy: the ability to rise or sink depending on one’s internal and external circumstances. Observing cordwood’s interactions in nature undergirded what Lundburg describes as interconnectedness—how each decision we make in turn affects other decisions, an endless ripple effect influenced by personal strengths and weaknesses, resources or the absence of them, and the people individuals surround themselves with. Lundburg says, “All of these factors affect how we collectively or individually rise or become submerged.”

With achieving financial stability in Hawai‘i often a Sisyphean task, the “starving artist” who strikes gold and now lives comfortably off her art alone is the exception rather than the rule. “When you go to art school, you’re told the odds are stacked against you,” Tallett says. For Lundburg and Tallett, being artists requires a twin mindset of creativity and pragmatism. Though long-established and active as artists, both still hold full-time jobs in order to support their family, which includes their teenage daughter, Kia‘i. But making ends meet is no easy task, and it is made more challenging by their decision to live in a rural area on Hawai‘i Island where creative career opportunities are scarce and tough decisions arise at the intersection of priorities, passions, and paycheck.

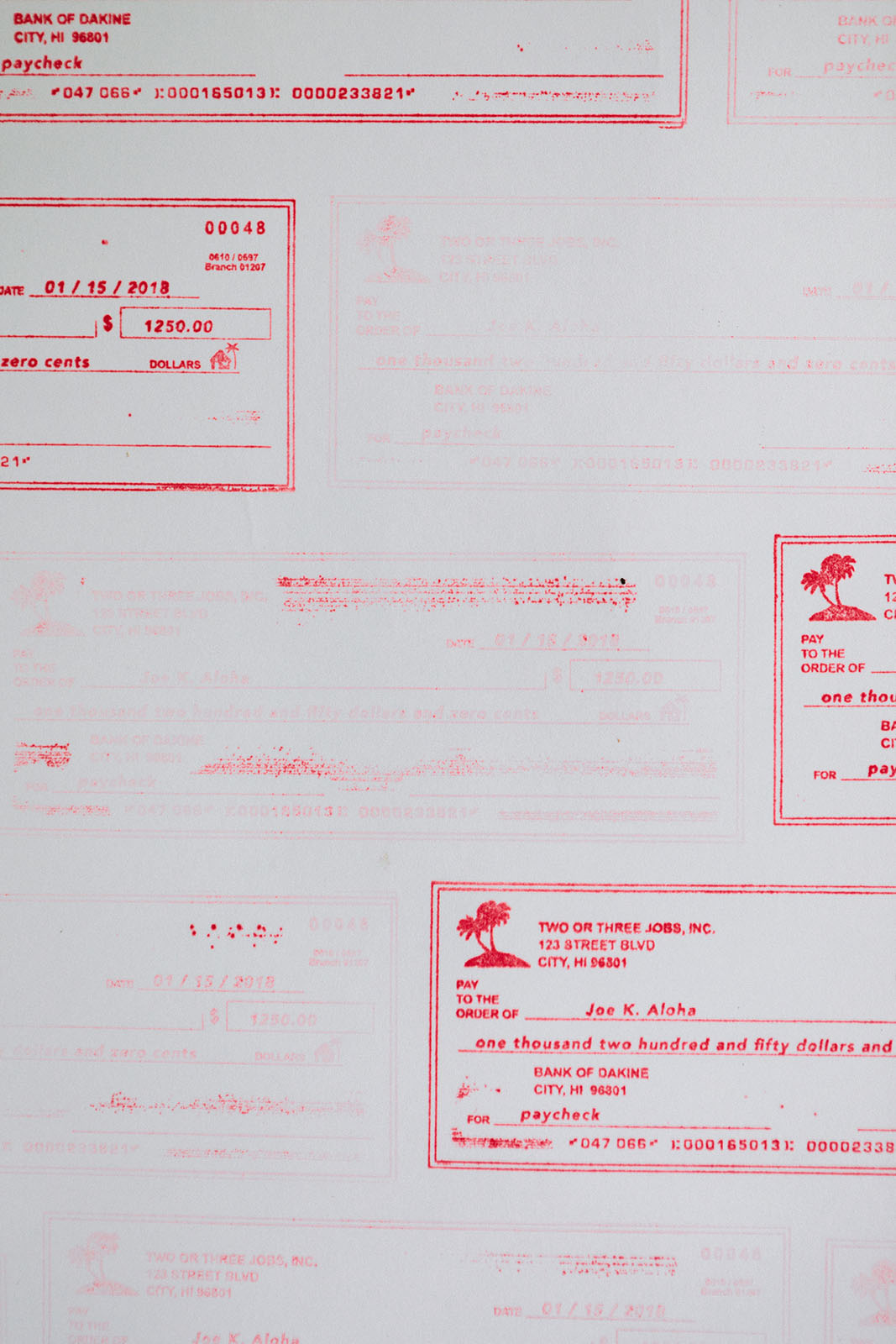

These sentiments are confronted in Tallett’s piece titled Paycheck 2 Paycheck. At the couple’s studio on their property, a massive roll of white cotton rag paper hangs near the ceiling’s edge and unspools to the floor like a massive receipt. It is systematically stamped with an unusual design: custom-made, large-scale images of paychecks. Covered with rows upon rows of crimson paychecks—Tallett chose the color red to speak to being “in the red,” fiscally—the piece looms like a formidable brick wall. Upon closer scrutiny, each stamp is a cryptograph of sorts that reveals a cache of information. The graphics reflect the sobering data found in the ALICE Report, which include everything from housing needs to income statistics to the ongoing pressures of having to stretch one paycheck long enough to meet the next. The mixed-media piece showcases how a limited income is not just a disadvantage but a palpable barrier to financial security. In the most trying times, Tallett muses, it feels like an insurmountable wall.

Creating art inspired by the stark financial realities so many Hawai‘i households face has struck home for Lundburg and Tallett. But it has also reminded them that their choices reflect their purposeful decision to live as artists regardless of income stability. “We are kind of further away from the sun,” Tallett concedes. However, wealth can be framed in a variety of ways, including what one chooses to do. “Our heads and minds are rarely still,” Lundburg says. “We want to be doing this. We imagine the life we want to live, and then figure out how we make it happen.”