Images by Matt Shallenberger

When I was young, I made maps. For a while, we lived in a house in Virginia with woods behind it: three small forests, connected by a long stream, interrupted by a marsh with winter goose nests. I named the regions of the forest as if I were an archaeologist, imagining villages and roads erased over time, traces so subtle that only I could see them. As a landscape photographer, I see every image as an attempt to get back to that experience, finding places I would have named as a kid.

Both sides of my mother’s family left Portugal for Hawai‘i in the 1880s to work in sugarcane. She was born on the Big Island, a few weeks before the end of World War II. My father’s family is from Austria, by way of California. A biologist, he came to Hawai‘i in the 1960s to study native bird life. I was born on O‘ahu 100 years after my ancestors immigrated, and 200 years after the first European landfall.

When I was 7 years old, my dad’s work took us to Virginia, Oregon, New Mexico, and then to Virginia again. My parents moved back to the islands when I left for college, and now they live near Waimea, on the last remnant of what was my grandfather’s cattle ranch. Most of my mother’s family resides somewhere near where their forbearers first settled, along the Hāmākua Coast.

More by coincidence than by design, each photography series of mine begins with finding a book. In my parents’ house, the Kumulipo is mixed in among histories, field guides, and family photo albums. I’m sure I saw it as a kid, but I was never formally introduced to it. The Kumulipo is popularly known as the “song of creation,” and describes the cosmological beginnings of Hawai‘i through to the birth of animals, plants, gods, and men. Conceived and memorized centuries ago by haku mele, or chant-tellers, the Kumulipo serves various purposes. Like the stories in my mother’s family, it connects children to their lines of ancestry. Like my father’s biological taxonomies, it classifies and organizes all the forms of animal and plant life. The themes, modes, and landscapes were all familiar to me. Rediscovering the Kumulipo as an adult, while visiting my parents, was like finding a map of a forest I already knew intimately. This became a conceptual starting point for exploring my

own history.

I studied the Kumulipo first as a work of poetry, comparing different translations, and focusing on the way the story was told: stories reflecting upon one another, paired opposites, similar and repeated symbols describing birth and death, cultivation, world creation, genealogy. The Kumulipo was meant to tell several stories simultaneously—political, environmental, personal, historical. It incorporated hidden meanings, known as kaona, to connect the layers. After studying as many interpretations as I could find, I copied out the poem, combining different translations and removing all annotation, filling the holes with my own scattered notes. I made my first map since childhood, marking places significant to my family history. And then I took pictures.

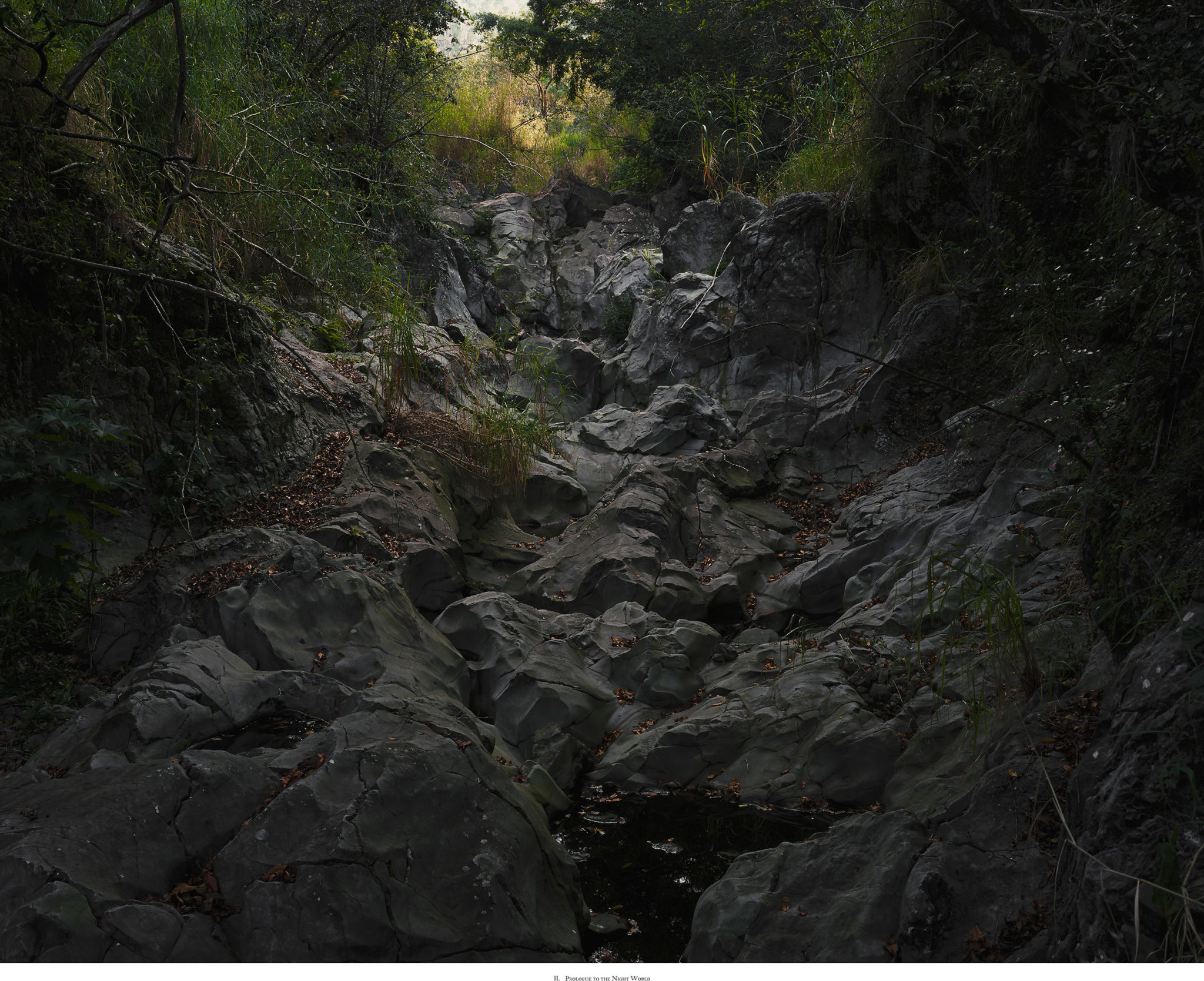

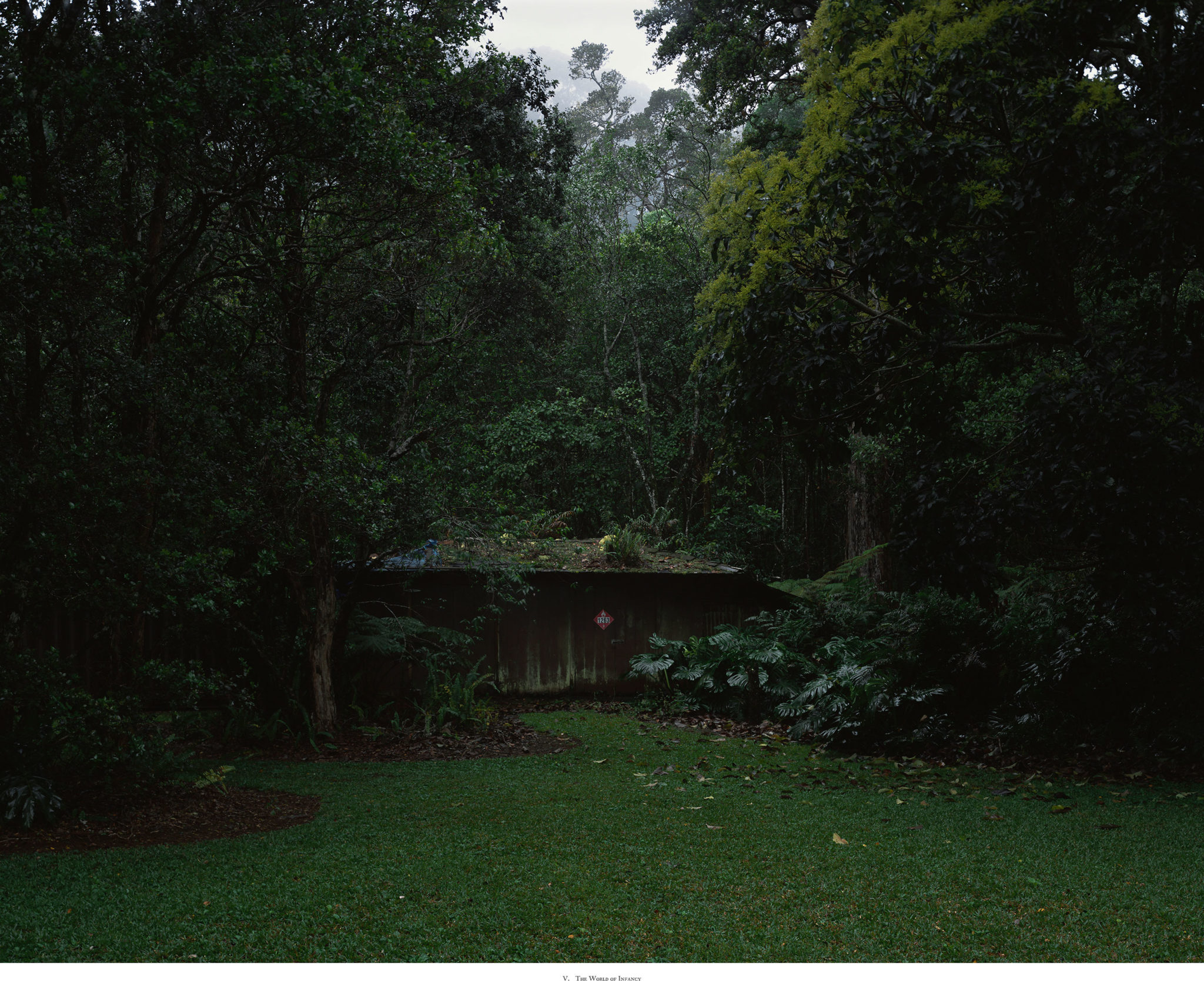

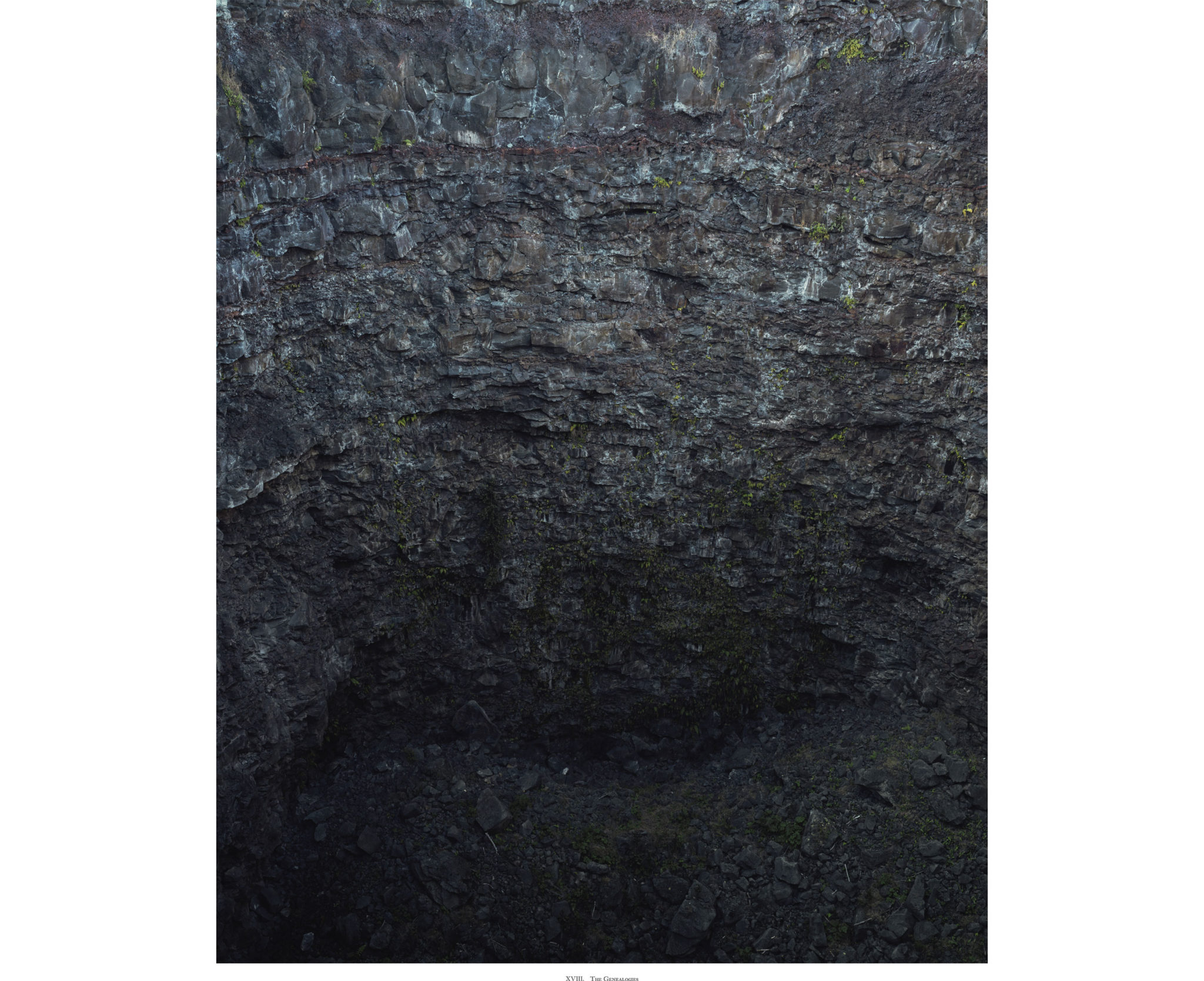

Each of the photographs is a large-format film landscape of a place with some significance to me or my family history, with each titled after a chapter in Martha Beckwith’s 1951 translation and commentary. In my photographs, some of the interpretations are literal, attempts to illustrate scenes from the stories. Others are metaphorical, or personal. Most are a foggy combination of all three.

The first photograph in the series is titled “The Master of Song.” In this chapter, Beckwith examines the haku mele himself, describing his vocal style and use of layered imagery. My photograph shows a cement pylon deep in Ka‘awali‘i Gulch, a remnant from one of many trestle bridges built for trains that carried sugar up and down the Hāmakua Coast. Above this is where my great-great-grandfather built his house. Like many of the relics of industry, the pylon has been overtaken by the forest, and is now difficult to place in time or scale. It is, for me, a totem, a place to appeal to my own ancestors, my own family gods.

People often assume that photographs are meant to say something specific, but more often than not, they’re an unpredictable mix of intent and instinct, and are offered as questions rather than statements. After sequencing and titling the series, I reached out to learn what it reveals to people with different relationships to Hawai‘i: conservationists like my father, who see a story of invasive species taking over native ones; immigrants, like those in my mother’s family, who see the small evidences of their history, the cement among the lava; mainlanders who have never been to Hawai‘i, who see a landscape more violent and complex than the idyllic paradise they’ve been painted; and Native Hawaiians, who see the conflict between the landscape of the Kumulipo’s time and that of today, altered by colonization and industry.

That’s one of the reasons I call this series The Leaping Place. The title refers to ka-leina-a-ku-‘uhane: places from which departed souls begin their journeys to the underworld. Some of these locations are commonly known, and others are a mystery. These are the places where we return to the beginning. I come from Hawai‘i as a kama‘āina (local) but not a kanaka maoli (Native Hawaiian), returning home but also discovering. Hawai‘i is made up of countless stories. I envision leaping places as pathways to our common past, and to conversations about our shared present. Each photograph is a haunted step back into my own history, and a chance to ask others about theirs. And for those whom I never meet, perhaps it’s a place on their own journeys to stop and imagine.

(titled after Martha Beckwith’s Kumulipo chapters, 1951)