A reflection on Hawai‘i’s intimate relationship with the most feared creatures of the ocean.

When I was in high school, I wanted to be an animal behaviorist. For a senior assignment, I had to shadow someone with my dream job, and the closest I could get was the management of a wolf sanctuary. Volunteers were boiling chickens to feed the wolves and wolf-dog hybrids when I showed up. After explaining what I wanted to do, one of them told me to forget it. You can’t see animals in the wild, he said. The instant humans are around, their behavior changes. Instead, he suggested, study humans.

In the summer of 2015, North Carolina experienced a rash of shark bites in shallow waters—eight, to be exact. There are 50 types of sharks off the shores of the state, of which 10 are known to have bitten humans; no one can be sure of the exact culprits, or the cause. Two encounters resulted in lost limbs, meaning these were probably perpetrated by bull or tiger sharks. The series of events sparked national and international chatter, and a wide array of speculation about why this summer was so risky, ranging from a “shift in ecology” to the fact that it had been unusually hot, meaning people were flocking to the beach.

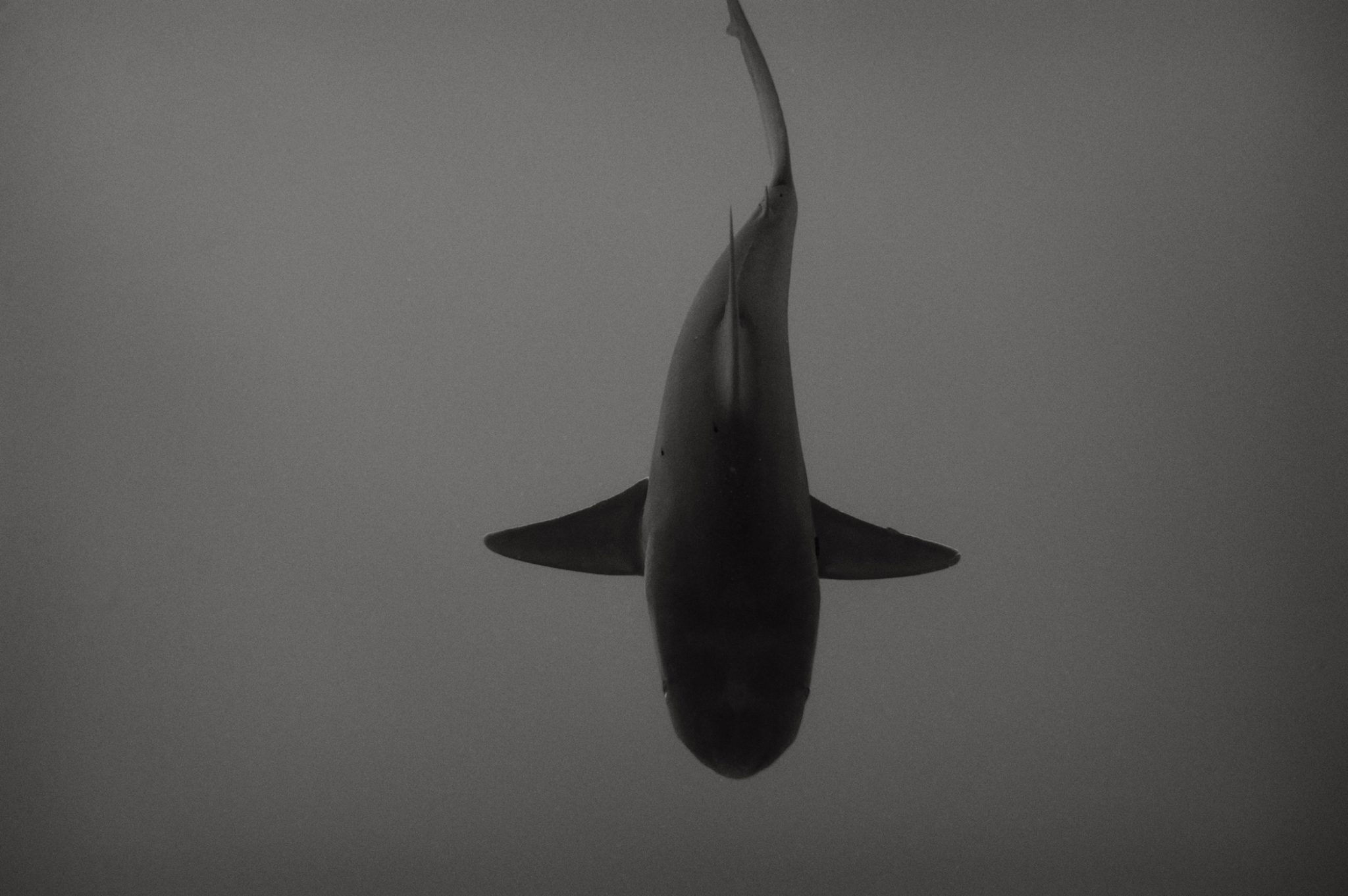

But humans, it turns out, are a much greater threat to sharks. In 2010 alone, it is estimated that up to 97 million sharks were caught as by-catch, for sport, or for their fins. Despite such statistics, humans still largely fear the creatures. This is because they are at home in a world that humans have never fully adapted to but continually enter. Sharks roam waters around the world, even those alongside urban areas, and are incredibly quick and agile; comparatively, humans are pitifully clueless and defenseless animals in the ocean. Even brief, mistaken encounters between the two can leave individuals badly hurt. To regain control of this situation, humans have turned to culling, research, and face-on encounters.

In Hawai‘i, the relationships humans have with sharks vary. My hairdresser, whose family is from the islands but who grew up for part of her youth on the mainland, rarely goes into the ocean—when she does, she gets chicken skin because she imagines a shark is near. Surfers frequent spots like Electric Beach, even though it’s known shark territory. Some Hawaiians still consider the creatures ‘aumākua, or sacred ancestors. Visitors and locals go on tours to swim with the toothy predators, snapping pictures with GoPros for Instagram accounts, telling stories of near misses; stories of how they have learned to love a creature they once feared, and still kind of do.

Including those that can be seen on such tours on O‘ahu’s North Shore—sandbar sharks, grey reef sharks, Galapagos, and the rare hammerhead or tiger sharks—there are 34 species that frequent Hawai‘i waters. (To say “shark” muddles the array of these animals, which range greatly in size, makeup, and behavior, but it’s the easiest way to group them.) This includes great whites, which only make rare appearances here. There are records of ancient Hawaiian chiefs canoe-fishing for large sharks, which they called niuhi, thought to be tiger and even great white sharks. “They could be tamed like pet pigs and be tickled and patted on the head,” wrote Hawaiian historian Samuel Kamakau of niuhi in an essay translated for a volume composed of his writings, Ka Po‘e Kahiko: The People of Old.

Hawaiian stories confirm that sharks have been here as long as we can know, and that even then, the relationship between man and beast was fraught with ambiguity. In these ancient tales, sharks run the gamut from villain to god to victim. One story tells of a “shark man” who preys on travelers headed to pick ‘opihi—he runs ahead, morphs from human to shark, and gobbles them up. Another tells of Pehu, the man-eating shark of Maui, lying in wait for a surfer to eat in Waikīkī. A third involves Pearl Harbor’s guardian shark, Ka‘ahupāhau, who considers man-eating sharks to be bad, and notifies fishermen when a group of both good and bad sharks enters the harbor. Unfortunately, neither she nor the fishermen can distinguish the man-eaters, so all the sharks are hauled to shore and left to die in the heat.

In the second half of the 1900s, the state of Hawai‘i authorized shark culling in an attempt to make the waters safer for humans—there were at least eight deaths in the 1950s in which signs pointed to tiger sharks as culprits, though at least one may have been unassociated. From 1959 to 1976, a total of 4,668 sharks were caught and killed, of which 554 were tiger sharks, the type most likely to bite humans in Hawai‘i (they rank second to great whites worldwide). In spite of the culling, there was no significant decrease in the rate of shark bites during or after, according to the Hawai‘i Institute of Marine Biology. In 2013, after two fatal encounters in Maui County in one month, culling was considered again—this, despite research showing that lone tiger sharks don’t remain in a set area, nor do they take on special preference for human flesh. For institute researcher Carl Meyer, this ongoing conversation about culling is a philosophical debate, one about “whether it is ethical to kill large predators in order to make the natural environment a safer playground for humans.”

The first shark tour on O‘ahu’s North Shore opened in 2001, offering cage dives for snorkelers, who float behind metal bars at the ocean’s surface roughly three miles off the coast of Hale‘iwa Harbor, where Hawai‘i waters end and international waters begin. Sharks started coming here in larger numbers in the 1960s, when a crab fisherman began crabbing in the area and tossed his day-old bait from traps overboard, an easy meal for sharks. Now, to entice them to rise from the depths, tour boat captains play with their engines, which emit electrical currents; some tug at lines attached to objects on the ocean floor, simulating a crab fisherman hauling in his cage. Depending on the company and the pressure to deliver, operators may or may not also toss fish into the water before or during dives—but to bring this topic up is to warrant offense, since chumming for shark tours is both taboo and illegal in Hawai‘i—though not in international waters. (Fishermen, on the other hand, can still chum and toss old bait overboard anywhere.)

The two cage tours here have had a spotted record in the community because of exactly this practice. In 2011, over the course of several months, three North Shore Shark Adventure tour boats were burned in Hale‘iwa Harbor. While the motive behind the arson was never confirmed, five workers from North Shore Shark Adventures and Hawaii Shark Encounters had been arrested for feeding sharks within Hawai‘i waters, and there were fears in the community that hungry sharks were following operators’ boats back to the harbor, and near to human activity. But the Institute of Marine Biology had already dispelled this theory in 2009, with a research paper that concluded that sharks remain at cage diving sites throughout the day and disperse at night. Sharks that visited the dive sites even migrate seasonally to deep waters off the west side of O‘ahu, going as faraway as Maui and Kaua‘i.

In contrast to cage tours, two cage-free tours now also set out from the harbor. Instead of offering an adrenaline rush from behind bars, these tours count on an extra push of human confidence and curiosity (or, perhaps, bravado). The fact that tour-goers are willing to pay for such excursions is also a sign that we have become a bit more savvy about sharks. The first of such tours to set up shop was One Ocean Diving. Co-owned by diver and conservationist Ocean Ramsey and photographer Juan Oliphant, One Ocean started off as a research endeavor in 2010, and expanded to offer cage-free tours out of Hale‘iwa in 2013. Last year, Islandview Hawai‘i, which began offering snorkeling tours off Waimea Bay in 2013, joined the fray—its founder, Kaiwi Berry, is the grandson of the crab fisherman whose day-old bait first began attracting sharks to the area in larger numbers. Cage-free tour operators believe that the creatures can be trusted when encountered in situations in which they feel secure and submissive, and those in which humans are not easily confused for potential meals. It helps that roughly 98 percent of sharks seen on tours in the area are Galapagos and sandbar sharks, species very rarely involved in shark bites. The other two percent are tiger sharks.

On my first cage-free shark dive, I didn’t realize how nervous I was until I got out of the water and slowly unclenched my jaw from around the mouthpiece of my snorkel; we had seen Galapagos and grey reef sharks, and while two swam parallel just 20 feet ahead, I couldn’t stop wondering what was at our backs. On my second tour, several of us glimpsed a hammerhead in the distant blue. Tours rarely come across this type of shark, and it felt like a special, shared experience with the others in the water, and with the creature—even though it could hardly care that I was there.

But sometimes, certain sharks do care. On September 20, a spearfisher diving in a cave off the Big Island came face to face with a jaw-gaping tiger shark, which he grabbed on the nose. It chomped him on the leg, then he punched it, and it swam away (sharks rarely stick around for more than one bite). Why it attacked him will never be known—it could have been hunting for fish, or it could have been a territorial warning that he countered with aggression. As of October 2015, there have been a recorded 62 shark bites of snorkelers, fishermen, surfers, and swimmers (but no tour-goers) in the islands since 1995. While justifications of such bites vary, theories include acts of defense, curiosity, and mistaken identity. Sharks feel things out with their teeth. Unlike what Ka‘ahupāhau thought and what we would like to believe, there are no good sharks to befriend or bad sharks to defeat—there is only nature, which we try our hardest to but cannot control.

This story is part of our The Sea Issue.