A beloved Japanese card game inspires a curious body of work that conjures paradoxical feelings of familiarity and displacement.

Will Matsuda’s photo project Hanafuda is a test of memory and recognition. Scanning the series of photographs, I identify a crumpled iris blossom, a pale pink peony, a darkened hillside, and a nimble doe. To anyone unfamiliar with the Japanese card game, these images are nothing more than flora and fauna. But to Japanese Americans like me, they coincide with the faces of hanafuda cards and also recall childhood memories of friendly competition with one’s obachan. I don’t remember at what age I learned to play, but I do know every visit to granny’s house prompted multiple rounds of hanafuda. The desirable gaji card always incited squeals of delight and the beautiful sakura cards were worn from handling.

Matsuda’s Hanafuda treads a fine line between reimagining and recreating the timeless prints of the beloved game. Unlike Western playing cards, hanafuda is void of numbers or conventional suits, instead depicting flower and animal prints representing the 12 months in a calendar year. Matsuda, who learned how to play at a young age from his Grandma Amy, still doesn’t understand all the rules. Growing up in Portland, Oregon, he only played hanafuda once a year when he and his immediate family visited his grandma on O‘ahu for the holidays. He fondly remembers losing to her, claiming she didn’t hold back in leveraging her years of experience. It was this nostalgia that prompted Matsuda to create 25 vertical photographs of scenes reenvisioning hanafuda prints.

“If I put myself in the photos, I find it to be an easier way to access these more complicated ideas.”

Will Matsuda

At the time, Matsuda was living in New York for a residency at The Center for Photography at Woodstock. While on a leisurely stroll in the Catskill Mountains, he recognized a variety of the same plants, such as wisteria and iris, depicted on the hanafuda cards he played in childhood. Intrigued, he learned that Woodstock is on the same latitude as northern Japan, which would account for the similarity in foliage. Consequently, Hanafuda ended up being shot at an unconventional Western location with Japanese subjects.

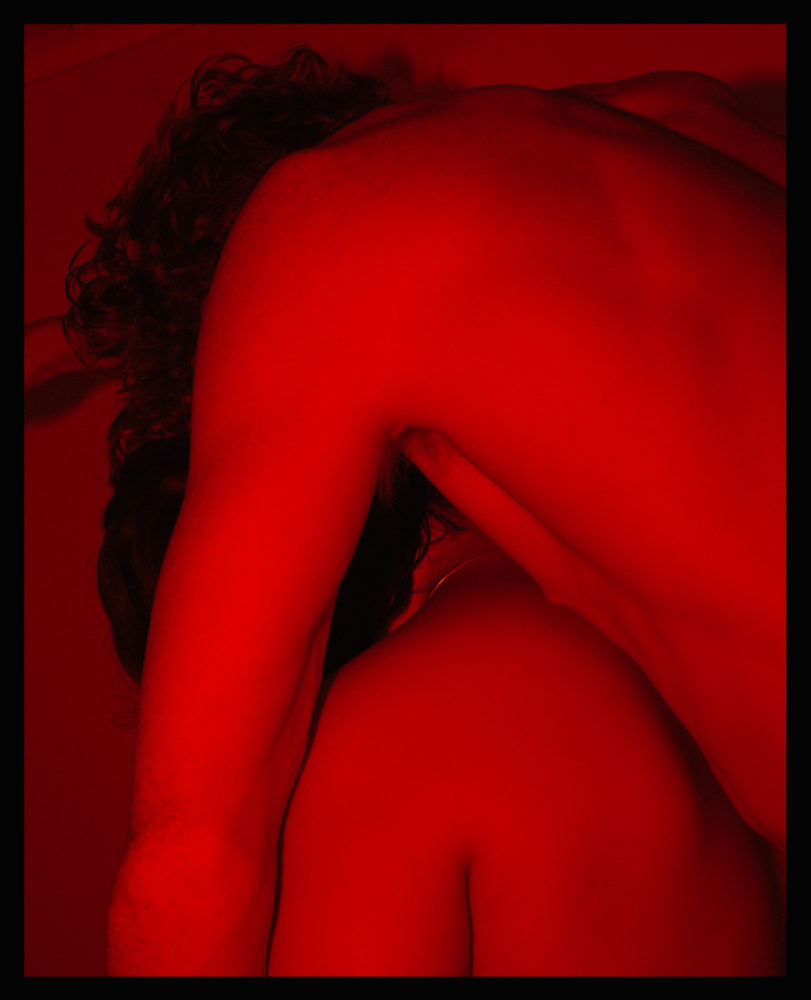

Matsuda knew he wanted the series to have a human presence, and as one of the few Japanese Americans in the area, he often cast himself as the subject. “I was thinking of these cards as a metaphor and vehicle to think about Japanese American culture and identity,” he says. “If I put myself in the photos, I find it to be an easier way to access these more complicated ideas.” As a result, the series conjures paradoxical feelings of familiarity and displacement. Matsuda’s Asian features are a familiar sight in Hawai‘i or Japan, but as he poses among North American pine trees, against a black sheet, and below a starry sky in upstate New York, he creates a universal space neither distinctly Japanese nor American. There is a sense of longing for Japanese culture, an attempt to “find the bits we can latch onto or belong to, wherever we are,” Matsuda says.

Throughout the process, Matsuda worried less about imitating the hanafuda prints exactly and more on offering his own interpretations. This artistic choice points to the way the game evolved over time. The cards date back to the 17th century, when the Tokugawa shogunate, a military dictatorship, implemented a ban on foreign playing cards. Gamblers responded by creating new cards that coyly imitated Western cards. These imitation decks were still banned, leading to the production of hanafuda, which was distinctly domestic in appearance by its popular Japanese images. Nevertheless, the game was played in secret in gambling circles. Eventually it evolved from a gambling game to a household pastime and was brought over to Hawai‘i by Japanese immigrants during the 19th century.

As a Japanese American with ties to Hawai‘i, Matsuda was in a unique position to conceive of and photograph his series. Within a canon of primarily white men, the photography industry has done little to diversify its community of photographers, photo editors, and critics. History has often been told through the lens of white people and not by those who experienced it firsthand. For Matsuda, Hanafuda was a way to help rewrite history by telling a story of Japanese identity from the perspective of a Japanese American.

If hanafuda tells the story of issei Japanese in America, Matsuda’s Hanafuda represents the generations to follow, who navigate traditional and modern identities. It’s telling that he had to reference the original prints to produce new images suitable to him. For Japanese Americans, our identity is inevitably shaped by history, culture, and traditions. But this need not stop us from re-inventing what it means to be a Japanese American today.